Alexandra Horowitz, On Looking: “It could be a happy accident of pigmentation, this interest in each other’s eyes. The sclera of our eyes lost its dark coloration somewhere on the route between chimpanzee and human. With the whites of my eyes as backdrop to my bright blue irises, the direction of my gaze suddenly becomes plainly distinct…

What pure disappointment those evolutionary developments must have been to their first bearers. Just when they thought that their attention was private, now everyone else could read it on their faces. It could be no worse if a Magic Marker traced a circle around your genitals when you felt attracted to someone, or your forehead scrolled the text rambling through your head in private thoughts.”

John Burroughs via Alexandra Horowitz: “To find new things, take the path you took yesterday.”

Outside the Night and Day a one-eyed man sitting on the pavement next to the money machine says to me, “Can you help me?”

It’s a good opener. It hooks me with its directness. “What do you need?”

“I want to sleep in the shelter tonight, and it costs ten bucks. Last night I didn’t make ten and I had to sleep outside.”

It doesn’t matter, really, whether I believe him. I like his boldness, Winter’s truly here, and I can spare ten. (The pink membranes of his eye-socket, like wet petals.) I’m opening my satchel, but I already know I’ve got nothing small.

“Could you get it out of there?” he says, pointing to the money machine. While I’m typing in my PIN between the rubber flaps, his larger, scarier-looking friend comes to confer with him and they have a low-toned ten-second talk I can’t make out. My guy’s prettier, quicker, visibly disabled— a more effective hustler. When the big friend leaves, he talks to me some more: “Yeah, being homeless sucks.”

Me: “I bet. And it’s getting cold now.”

I’m discovering that the machine only dispenses twenties.

“Yeah, last night was really fucking cold. Could you make it forty?”

I give him my usual line: “I look rich, but I’m actually poor.” (There was a time when— truly penniless— I knew I was poorer than most beggars, but that’s not the case any more.)

I decide to go into the Night and Day and change the twenty I know is in my bag. That seems petty, but I’m sticking to my guns. Now that I’ve embarked on this exchange I feel like I have to see it through, but I’m resolved to give what I choose to give.1 Emotional weather is happening inside me, a push and pull of empathy and resentment. Each logistical barrier is like a small wall that I have to jump over: his force of will driving me, my habit of frugality dragging me.

When I ask the young baseball-capped guy behind the counter2 if he can change a twenty for two tens, so I don’t have to buy anything— there’s nothing I want in there, I don’t even want to be in there— he reluctantly checks both tills. “I’m not really meant to, but just this one time, OK?” He holds the blue notes out to me across the counter interleaved between his fingers, and I tuck the green note into a spare finger-gap and pluck the blues.

I fold one ten away and step back out to hand the guy the other ten. “Here you go, my bro.”

“Thank you. Have a good night. God bless.”

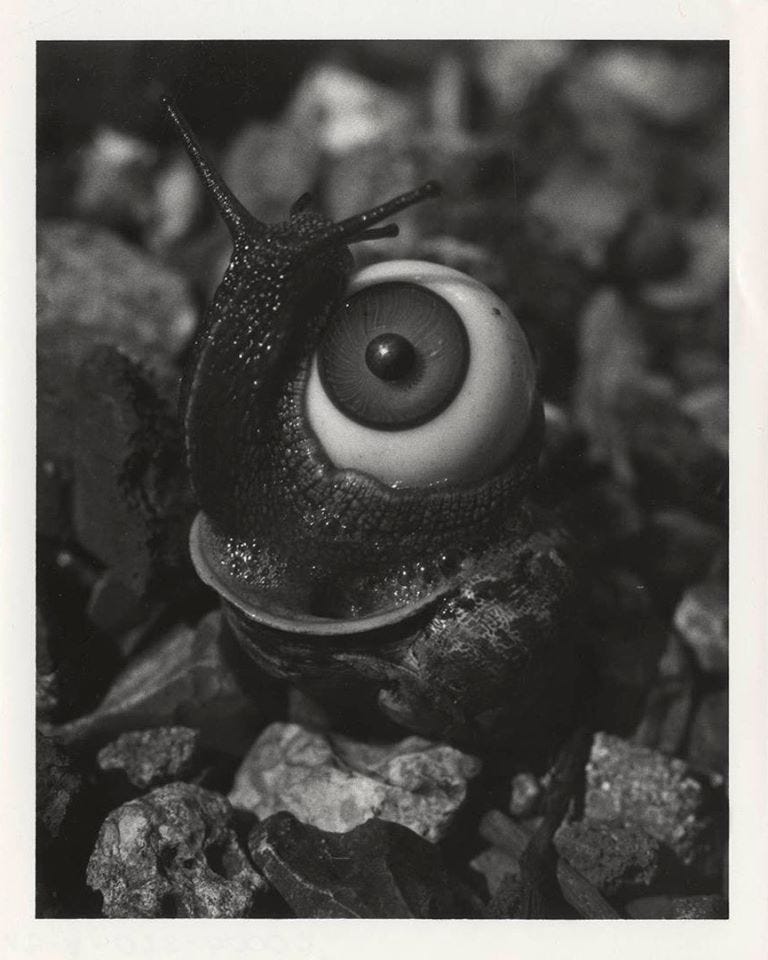

That morning I’d watched a video the algorithms thought I’d like, a guy getting a prosthetic eye made by the injection of some white goo— liquid silicone? from a big syringe directly into his eye socket. The set glob of white rubber with its chunky sprue was manoeuvred gently out of the lid, the lips of the eye stretching and clinging like labia.

The guy— an American— showed off his eye collection enthusiastically to camera. “Guess which one of my prosthetic eyes is the most valuable? This one right here—” He folds it gently into his socket— “Because it’s hand-painted to match my other eye, and moulded at the back so it moves a bit. It cost $10,000.”

Later, as I was writing it all down in my journal, I thought— this story is what I bought with my ten dollars.

My friend Philip’s new bookshop, Undercurrent, has opened where Happy used to be. (Corner of Tory and Vivian Streets.) When I walked down the old familiar stairs, I couldn’t place where things had been back then, where the bar was, the piano; too long ago, too remodelled.3

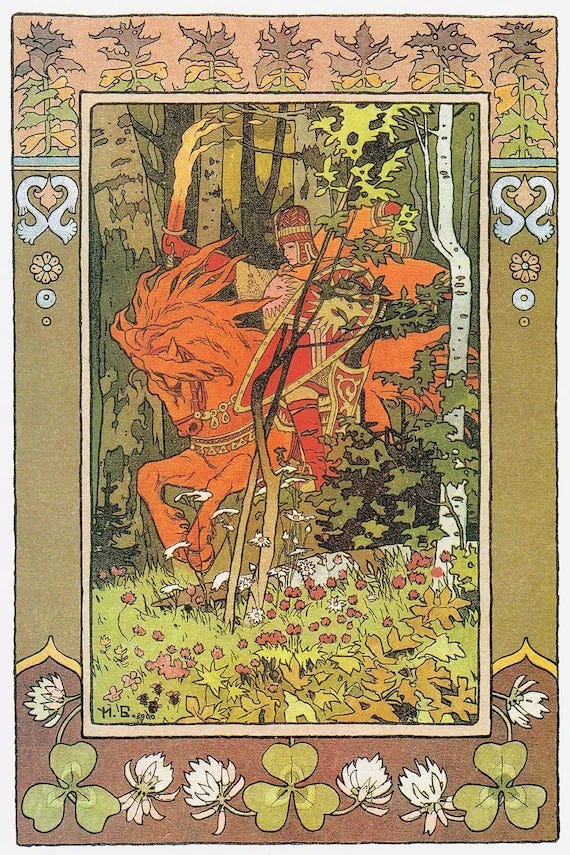

Looking at the book selection, I didn’t get the Tower-of-Babel panic-feeling a lot of bookshops give me (an overwhelming sense that everything’s already been written, and that everyone should probably just shut up). I found two books, both perfect: the one I quoted above— On Looking; A Walker’s Guide to the Art of Observation, by Alexandra Horowitz, which I’ve never heard of, but which could have been written especially for me— and a child’s book of nursery rhymes, Lavender’s Blue, that gave me the strangest feeling when I opened it. I knew by the timbre of my response that I must have been intimately acquainted with this book as a very small child. Imprinted on it like a duckling. The pictures struck sparks in my deep memory. Spotted horses in a stable. Dancing barefoot girls. Eleven, twelve, dig and delve. Daddy’s gone a-hunting.4 Hark, hark, the dogs do bark.

In the city, not all gazes are equal. Some are hungry; some are baited hooks. Foreigners with clipboards trying to sign you up to Médecins Sans Frontières or Amnesty International. Religious fanatics with their pamphlets and books. Invisibility technique involves seeing people before they see you, then avoiding eye contact. Eyes are slippery fish. The locked gaze is the hook in the mouth. That’s how they catch you.

(My friend Matt, who was brought up fundy-Christian, told me once that they had a term for dressing in a sexual manner, to draw attention to cleavage, say: eye-traps.)

Manners Street after dark. Young thugs walk stiff-bouncing, making noise and show. (It’s a trap— trying to draw the male gaze to spark a fight. Are you looking at my Missus? Are you saying she’s ugly then?) One swaggers through the bus stop, dressed in black with white accents: a white parallelogram on each wide-apart calf, mirrored like a butterfly’s wing-markings. A subdued girl follows three steps behind. His backwards cap, her false eyelashes. He slaps the bus timetable sign with an open palm, hard. BAM!

A smell of pancakes or waffles— burnt sugar— from some hole in the wall.5

A sudden rash of infantilism at the bus stop. A young person in puffy slippers. They keep talking about the slippers to their friends, like LOL! I am outside in my slippers, I can’t believe it!!

Someone else in a Harry Potter Oodie and flannelette pyjama pants. Their backpack is rucking up the Oodie at the back, which makes me want to straighten them out, tug it down.

Then someone appears clutching a big stuffed toy in one arm, the size of a human torso. It’s a cutesy rendition of a Plague Doctor, and the person fiddles compulsively with its long grey beak. When they sense me watching, they emanate annoyed Leave me alone vibes.

All these grown-arse adults out past their bedtime. I blame the Internet.

On bus. T-shirt on a teenager with a wispy moustache. White on black, all caps: MY SOUL CRIES OUT HALLELUJAH AND I THANK GOD FOR SAVING ME

Uz wunt be druv!

Think the pimply teenager from the Simpsons.

One of my first memories of Happy: coming down the steps and into the middle of someone’s wake. A suicide. Everyone was devastated, weeping. I was too new to the city to know anyone, an outsider in the midst of communal grief.

Pais Dinogad - Taranau / Sacred Knot

Translation here: Pais Dinogad (Dinogad's Smock)

I don’t need to know which one to picture the haughty, bored young European staffing it.

Love this one!

I walk down the street and see nothing as I am focused only on getting out of there as fast as I can.

You seem to embrace the city. Even when people irritate you a little your stories that feature them are filled with warmth and humour. And intelligence.

I can’t be like you but am happy you continue to observe! And report back.