William Blake, Proverbs of Hell:

“Improvement makes strait roads, but the crooked roads without Improvement,

are roads of Genius.”

This morning I went to Bunhill to see my old friend Daniel Defoe. The Winter sun had not yet cleared the tall brick and glass buildings. (The temperature was somewhere under 5°; there had still been frost on the fallen leaves half an hour earlier, when we dropped the little one off at nursery.) Bunhill, the Hill of Bones: the place where Defoe’s Plague Year protagonist ‘H.F.’ is buried in the book; the place where Defoe himself was buried in a pauper’s grave less than ten years after that publication.1

As I said a few postcards ago, it was my intent to take Defoe a coffee. I’d meant to go somewhere fancy to buy it, but when I stepped off the bus the closest coffee shop was a Pret, just across the street. I went in, reasoning to myself that Prets, which dot the London landscape like confetti, are probably the main place Londoners buy their coffee these days; still of the London-coffee lineage, descendants of the ones Defoe caffeinated himself at in the 1700s. But which coffee would he like? I considered an espresso— or a long black with cream? That’s what I sometimes drink. (The loophole is that this particular coffee is good value for money: a long black is cheap, and the cream, as a slightly unusual request, is often free. If you ask for cream on the side, it comes straight, in a little jug. But… Did they even drink coffee with milk in Defoe’s time? I wasn’t sure.)2 In the end I went for the coffee of my people, the flat white: two to take away. The paper cups were hot in my hands as I crossed the street and entered the stone gates marked with gilded names, bowing to the Dead on the way in. Inside the cemetery, the graves were behind locked fences— the first time I’ve seen that in England— but then, the stones were so old that they had melted like sugar, their carvings softening and rounding with the centuries. They were really packed in there, too, rows upon rows, and that’s not counting the unnumbered, unmarked Dead behind and below the named Dead. (It’s thought Bunhill has 123,000 inhabitants.)

The Dead here are nonconformists— religious dissenters, including Quakers, Baptists, Puritans, Methodists etc.: this outsiderhood was also why Defoe didn’t receive an education. (Blake, too, was home-schooled.) Both Defoe and Blake died in relative obscurity.3 For that reason I expected Defoe’s grave to be humble. Also, based on what I had seen from the bus, I thought Bunhill was going to be large— but it’s a mere pocket-handkerchief, and once inside the gate and looking at the map, I saw that it wasn’t going to be a long ramble to Defoe’s grave, as it was to Karl Marx’s. In fact, it was just around the next corner. I walked up the stone path, turned the corner and saw it— a tall, four-sided obelisk, like a public monument, a war memorial or some such, which seemed very weird. I went up to it. It all seemed too quick and easy, and in keeping with my first impression, the obelisk was weird: unmatching time-wise and design-wise to how I thought of Defoe. It seemed too square and big and pointy, and it had a coffin-lid-shaped bit pointing out of its root to North and South, as if it were a stone tree growing out of the stone apple pip in his stomach. It reminded me of vampires, a kind of weighing down. Then I saw that on the side of the obelisk were letters inlaid in lead, saying that it had been placed there as ‘A SUITABLE MEMORIAL’ by means of crowd-funding: ‘IT REPRESENTS THE UNITED CONTRIBUTIONS OF SEVENTEEN HUNDRED PERSONS’. There were two smaller gravestones placed next to it, at 90° to each other, with their corners close together, like the covers of a half-open book; and I saw that on the stone facing me it said William and Catherine Blake were buried ‘nearby’. (I felt sorry for the other guy, who had the chance misfortune to be the close grave-neighbour of two pilgrimage-magnets like Blake and Defoe.)

Pondering on this placement— apart from the crowd, but close to each other— I thought, well, Defoe came first: maybe Blake wanted to be near him? The sun was rising above the buildings now, casting light on the gravestones and the dead leaves scattered on the stone slabs underfoot, making long shadows. I was taking photos with my camera, which means I can’t show them to you; I’ll just have to tell. (The reason is that I hate taking photos in graveyards with smartphones.)

There were fresh but ugly flowers in a tin can in front of the Blakes’ stone, and suddenly I saw that people had left money on top of the stone, on the shoulders of it: copper coins against the green. Ten of the twelve coins were tuppences. (Why the two-penny predominance? What does it mean?) There was a big tree just a few steps away, with a melted candlewax look, and although it was bare of leaves I saw it was a fig, buckling the enclosing paving-stone frame with its humping roots and slowly swallowing the fence with its elephantine trunks.

There were two men— parks staff— doing something leaf-and-shed-related. They were chatting away, and again I felt the strangeness of the Colonial, the New Zealander in London: to them this was just their workplace. I was shy to perform my rites with witnesses— was it even OK to pour hot liquids into such sacred ground? What does coffee do to the soil? But that was my magical impulse, and as such I was bound to follow through. In a moment when they were both otherwise occupied I quickly uncapped the cup and poured the coffee into a gap between the paving stones and the grave-marker, onto a stripe of the black London soil. (Was that even the head end? The double-ended grave made it impossible to tell.)4 The coffee disappeared but the brown foam sat on the soil. I stood back and drank mine. We were hanging out now. Unfortunately, the coffee was quite bad. (Sorry, Daniel…) Syrup of soot and the essence of old shoes, like much English coffee. (Back in Aotearoa, my English friend Kat had advised me to bring a bag of coffee in my luggage, which I had done: but out of habit I brought espresso grind, which requires a stovetop espresso maker like I use at home. When I was with Ben and David from Eliza’s band yesterday morning in Northampton, I saw espresso makers in a roastery— but the steel ones were all six- and nine-cup, none so small as a two- or three-, which I might have considered buying.)

I hadn’t brought Blake anything. I felt this was poor manners. I looked in my bag for a coin, but found none.5 A song, then. I like to sing something age-appropriate, and I wanted something Defoe would have heard too, so I thought of the oldest songs I know, and quickly decided upon one of my favourites, Soldiers Three, which I learned from my friend Nigel (a fellow history-nerd, polymath, and Samuel Pepys fan). Also, the song mentions poverty, which dogged Defoe, Pepys… and me. (And maybe the other guy too, I can’t say: he died pretty young, though. Sorry, dude, I can’t even remember your name, now.) Lately come forth of the Low Countries, with never a penny of money. I started singing and found my voice had returned, for the first time since my cough. (“Yes, here in London we greet each other by coughing into each other’s mouths,” said Maddy, when I told her about how the people on the bus free-cough: they don’t cover their mouths, let alone practice such refinements as coughing into the elbow etc.)

As I sang I felt the song return to me line by line, almost-forgetting up until the next line came to my mouth. It flew out into the morning, filling the graveyard, and as I sang I saw, up on the trunk of one of the huge plane trees, illuminated by the rising sun, a London parakeet at its nest-hole— a knot where a branch was cut off long ago. These little green parrots have long tails which make a distinctive silhouette in flight, easily recognised, and their calls too stand out as not from here.6 (Another time I heard a super-weird bird call, but tracked it down as emanating from a grey squirrel— another feral beast, out-competing the red squirrels: though Ben and David told me there are reds up in Scotland, and somewhere else I forget now too.) Nobody knows exactly where the parrots came from, but their near ancestors were escapees from captivity, which makes me think of Werner Herzog’s Wheel of Time: the Buddhist monk purchasing birds from the bird-seller in order to let them go.

It’s always strange doing weird acts in public these days, because people seem to think everything’s a performance for their benefit. My preference would be to hang out with the Dead with no witnesses around, like I often get to do at home, but that’s not possible here. (When I was talking about Bunhill with Maddy afterwards, she said she used to live right by Bunhill: she said it’s the only green space for miles around. When I told her it used to be four acres, we realised she had probably lived on it, not beside it. I said there are bodies under all of London, probably, but they are super-concentrated right there for sure.) Once I finished singing I felt awkward. Like, how to end such a hangout? Maybe pilgrimages are always anti-climactic, like when you clock a computer game.7 I bowed to the two literary gentlemen, stepped away to the West, and took photos of the shadows of their graves for a bit. I wanted to catch the solar flare, but it wouldn’t deign to come into my camera. People were walking their dogs now, fancy breeds; it’s a boujee part of town, close to the middle.

Suddenly, just around the corner I noticed a large stone inlaid into the ground, out on its own— away from the fence— decorated all around with fresh flowers. When I walked up to it, I saw that THIS was the grave of William Blake, a flat slab, beautifully engraved. I give you the end of a golden string / Only wind it into a ball / It will lead you in at Heavens gate / Built in Jerusalems wall. They had picked this quote, I thought, because of the word Jerusalem. (For more detail on what Jerusalem actually meant to Blake himself, as opposed to the vaguely jingoistic but still excellent banger of a hymn it later became, please see

‘s excellent biography William Blake vs The World, which I wrote about here.) There were so many Blake quotes they could have chosen. They started popping up in my mind like mushrooms after lightning. His Proverbs of Hell are maybe the ones I think of most often: although lately it has been Some are born to sweet delight, some are born to endless night, rolling around my skull like the clapper in a bell. He’s just a genius, there’s no way around it. How does he do it, make something so simple yet so powerful? (In that regard he’s the opposite of Defoe, a loghorreac if ever there was one.) To my mind formal simplicity is the essence of genius, though that’s a matter of personal taste. Like Zen: just say it plain.I felt I should now sing again, to the real Blake— but there was a guy lingering close by with a plastic shopping bag, doing something on his phone, and he looked unfriendly. I waited for him to go away but he didn’t. He was in it for the long haul, texting infinitely in Bunhill. (Was he setting up a drug deal, or what? Unlike Highgate, this cemetery didn’t have visible cameras on trees, and unsurveilled space is a rarity in London.) I walked around the grave, taking photos on my camera. The rising sun was touching the border of fresh flowers, casting their shadows over the stone and illuminating the very beautiful calligraphic lettering, a masterful stone-cutting job.8 As I leaned against the tree, a young black dog on a lead ran up to me, and I patted it. Then it went and ate some bark, which its owner pried out of its mouth as if it were a baby, remarking to me that lichen is not good for dogs to eat. Really it was very young, a puppy, and I could see its ribs moving under its black fur, and I thought about how a dog eating bark was a kind of a pun.

I was going to have to sing regardless of all these people. Honour demanded it. I knew what I wanted to sing, which was John Ball: I felt it was Blakeish in its joyfulness and mysticism. I started singing quietly under my breath, one time through, getting progressively louder, then the song took proper hold of me and I closed my eyes and sang the first few verses again aloud. Who’ll be the lady, who will be the lord, when we are ruled by the love of one another? Who’ll be the lady, who will be the lord, in the light that is coming in the morning? When I stopped singing and opened my eyes, everything had gone psychedelic. This is a singing-on-graves phenomenon I have noted before, but like all things in this city, the time-vertigo intensifies things greatly— a strong time-trip, a heroic dose of history. The colours were bright, the sounds radiant, and the isness vibrating, almost pulsing.

I took a photo of Blake’s stone on my phone— a capitulation to modernity— so that I could send it to my Will Blake, then I walked off around the graveyard. Down the middle, the path is paved with stone slabs, worn away by feet in the centre, slightly dished, in the same way as ancient stairs. (I find this very beautiful.) As I walked down the path, I saw that although the stone slabs were foot-smoothed, there were carved words still visible along the edges: these stones, too, were grave markers. The idea of the Dead being underfoot, as in the old churches, is startling to me still. Being asked to walk on them feels strange. I paid a quick visit to John Bunyan (I sing his song, but haven’t read his book); then bowed to the Dead and walked out the gate.

I then went to the British Museum and looked at cuneiform tablets. Inscribed model of a sheep’s liver, for augury via placement of blemishes. Lunar eclipse omens, between the 14th and 21st days of the month. Bird omens, via appearance and behaviour. (I took a photo for Enrique.) Omens from patterns created by oil dropped on water, mainly about domestic matters. (When I was in Northampton, I had hopes of catching a glimpse of Alan Moore; likewise when I was in the British Museum, of Irving Finkel— but no dice in either case. I know Finkel is the boss of cuneiform at the Museum, and I have watched many videos of him. According to the Internet, “He has served as Assistant Keeper in the Department of Western Asiatic Antiquities at the British Museum since 1979.” That is, since the year I was born, 45 years ago.)

It was very weird to see in the flesh— in the metal, in the wood, in the stone, in the clay— objects I knew well from images; but the Museum soon overwhelmed me to the point of nausea. I’ve had some pretty weird Museum experiences in the past, but this was on another level. All those ancient and powerful Gods and Goddesses, angry at being treated wrongly, put behind glass and gawked at: the vibe in the Museum was a hyper-concentrated potion of deep-time and Colonialism, a kind of magickal prison wine. (When I saw the artefacts from my own place, I cried.) In a spasm of claustrophobia, I fought my way out through the swarms of schoolchildren and tourists to the fresh air. Kev has a good word, timesickness, meaning broadly nostalgic longing; but I had been literally timesick in the Museum, the overwhelm to end all overwhelms. How did people stand to work in there? (Also, when I hunted for postcards, as is my wont, I found they only sell them mounted, for 5 pounds a pop, which pissed me off. I almost bought a Dürer rhinoceros, but couldn’t bring myself to.)

Later on, after dark (that is, late afternoon) I was riding the bus home when I saw a Note from

(whose ‘stack is named after a Blake quote): Happy Birthday mboi William Blake. This information hit me like a splash of water. I checked, and it was true— William Blake was born 267 years ago today. Then I saw had also written a Blake’s-birthday post:In fact I had already been thinking of her while I was at the grave because of this post she made a few days ago, showing her pilgrimage to Bunhill to visit Blake (I think this was before the rediscovery of his actual resting place and the placing of the beautiful new stone, as her photos show the ‘Blake is nearby’ stone next to Defoe’s grave):

There’s a part in Just Kids where she describes her beloved, Robert Mapplethorpe, stealing a Blake print from his work by hiding it down his pants, because he feels that he and Patti deserve to own the print more than anyone else does. (I seem to remember he then destroys it out of paranoia about being discovered in the theft, still feeling that is better than anyone else having it, but I’m retelling from memory and I may be wrong.)

I wrote a comment underneath Patti’s post saying how I had visited Blake’s grave this morning, not knowing it was his birthday, and how I sang him a song, and she replied ‘that is wonderful’.

When I got into bed and picked up my book, The Great When by Alan Moore— a novel about the London inside London, the London of Ideas— I immediately came to this (the protagonist, Dennis Knuckleyard, is talking to Austin Osman Spare at the latter’s exhibition):9

“All this, it’s just bloody amazing. I don’t know how you can do the work you do, when you’re… You know. When you’re…’ Dennis trailed away to mumbles, but Spare laughed.

’Come on, boy. Spit it out. “When you’re stuck down an ‘ole no bigger than a coal scuttle and you can’t sit down for cats”, is that what you were gunna say? ‘ow do I unpack all o’ this out of a tiny little box like that? It’s a good question, Dennis, and yer needn’t look as if you’ve farted by just askin’ it. The answer is, that’s where the magic comes in. William Blake, at Fountain Court, ‘e lived in little digs off boiled bacon, an’ from that ‘e bodged up an ‘ole universe.”

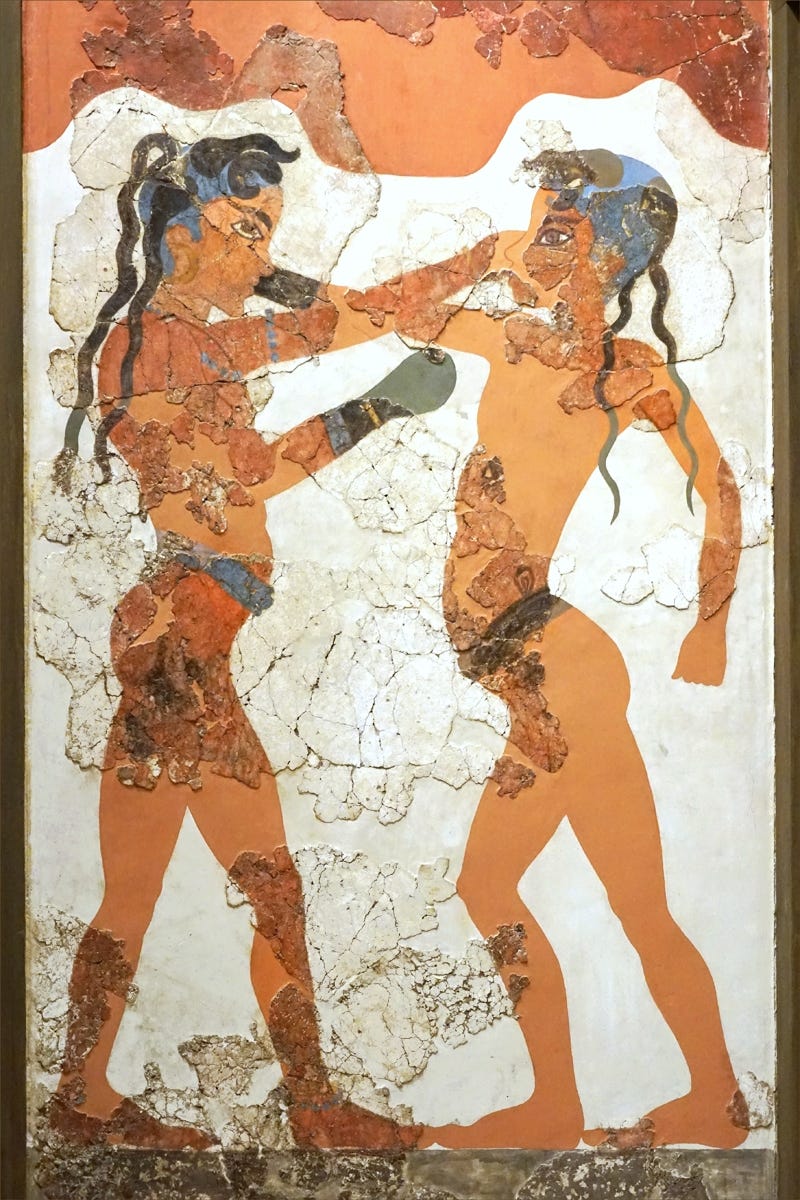

Oh— I quite forgot to say which postcard I’m writing this on— let’s say it’s the one I’m using for a bookmark, which I got from a Tottenham charity shop for 50p: the fresco of the boxing boys from Akrotiri.

Love,

Rose

Some think H.F. is Defoe’s Uncle, Henry Foe.

I found this, too, while searching Defoe pauper’s grave: Epitaph.

(Pauper ubique jacet is an Elizabeth I quote meaning Everywhere the poor man is despised.)

I wrote a great deal about Defoe and 17th / 18th century London during lockdown, but it was on The Platform of the Damned, which I don’t have access to while I’m here.

A good succinct essay on London’s eighteenth-century coffeehouses here: https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/the-lost-world-of-the-london-coffeehouse/

“One early sampler likened it to a ‘syrup of soot and the essence of old shoes’ while others were reminded of oil, ink, soot, mud, damp and shit. Nonetheless, people loved how the ‘bitter Mohammedan gruel’, as The London Spy described it in 1701, kindled conversations, fired debates, sparked ideas and… made one ‘fit for business.”

At least Defoe saw some literary success in his own lifetime— Blake struggled all his life, sustained only by inner light (and is buried in the same grave as seven other people). Verily I say unto you, No prophet is accepted in his own country (/time). Posthumous fame is cold comfort.

It turned out I needn’t have worried about such niceties, as it’s not quite clear that spot is even exactly where he’s buried. (Complicating matters, he was buried under a wrong name: some think this was to elude creditors.)

And thought, as I often do, of the song at 13.53 in this video: Cashless Company by Lisa O’Neill.

More about the feral London parakeets here: London's Parakeets: Everything You Need To Know

Second time in a month I’ve compared a graveyard to a computer game— I also felt that getting into Highgate had that vibe.

Where had I read about stone-cutting recently? It was in

of Rune Soup’s very good recent piece:I own a handmade printing of Spare’s tarot deck, made for me by my friend Ben. It’s very personal and self-referential, with notes on the cards themselves describing their meanings.

The day after singing to Blake on his birthday, my Godmother messaged me in the morning telling me to go to Treadwell's. She said it was the true magicest bookshop in London. When I walked in the door, Rob was saying to the counter-person "When I emerged from the Tube station, there were Welsh boys in the street singing Jerusalem..."

That was enough of a sign for me. I asked if they had Tarot readers in, and when the person behind the counter pointed at Rob and said he was the reader, I electronically crossed his palm with silver, and he took me into a small room wallpapered with exotic birds and read my cards with poetic precision. I knew he was a fellow Wizard just by one look in his eyes, and sure enough it was one of the best readings I've ever had-- I say that as a Tarot-Wizard myself. Often when people read for me I'm like, 'Yes, but also no,' but in the case of Rob, I was still thinking about what he had said days and days later.

So if you're in the vicinity of London and mystified about something, go see Rob and tell him I sent you. He's a Wizard's Wizard.

https://www.treadwells-london.com/rob

That’s such a visceral reaction to the British Museum, Rosie. I haven’t visited it for several years. I’ve sometimes found it overwhelming in terms of size, or been awestruck or occasionally creeped out. I haven’t felt the kind of claustrophobia you describe, but I’m visiting as a Brit. Really interesting to hear your perspective.

You’re packing a lot of culture into your trip. Enjoying these accounts, thank you.