Antarctica

Notes from a talk / Artists in Antarctica; Ice-consciousness; Werner Herzog; Dancing girls; Dream-orchids; A poem

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Left Hand of Darkness: “Sometimes as I am falling asleep in a dark, quiet room I have for a moment a great and treasurable illusion of the past. The wall of a tent leans up over my face, not visible but audible, a slanting plane of faint sound: the susurrus of blown snow. Nothing can be seen. The light-emission of the Chabe stove is cut off, and it exists only as a sphere of heat, a heart of warmth. The faint dampness and comforting cling of my sleeping-bag; the sound of the snow; barely audible, Estraven’s breathing as he sleeps; darkness. Nothing else. We are inside, the two of us, in shelter, at rest, at the center of all things. Outside, as always, lies the great darkness, the cold, death’s solitude.”

Antarctica: named for what it isn’t.1 It doesn’t have an indigenous name, because it has never had any indigenous people. I think about Antarctica fairly often, in the sense of Antarctica is over there. My view is over Raukawa Moana, Cook Strait, and the three-quarters of the horizon that isn’t filled with the mountains of Te Waipounamu, the South Island, is an empty line: the sea curves away, the globe’s liquid skin, ocean all the way to Antarctica. I’ve written before about how the whales pass by here on their journey North, Cook Strait being a kind of sea-mammal Panama Canal between the cold Southern Ocean and the balmy Pacific. The Anglo-Saxons, with their habit of riddling names, called the sea (among dozens of other poetic names) hwælweġ:2 the whale-way.

The sea leopards, the leopard seals, that come to my beach sometimes are the closest I’ve come to seeing Antarctica. Their coloration— silvery, grey, as if splotched with ice-light— references another landscape altogether. White is a colour too, as one of the artists said.

It was Winter’s Eve and I was angry, despairing. Reading the news, raging at this fucking Government and the distinct lack of meaningful opposition to it. Acute cabin fever: I had to get out of the house. I looked on the Internet to find something to do. There was a talk— Artists in Antarctica, at the Newtown Community Centre.

When I think about Antarctica, I see its mapped form, the way the edges spiral, like our galaxy, like cream dropped in stirred coffee. This interior vision inspired my outfit. I wore this shirt, which I recently bought in Shenanigans, the big craft shop in the main street of Shannon.

(A quick note regarding accuracy of quotation: I didn’t write down exactly what people said, with the exception of Anne Noble. When I’m taking notes I can’t really listen, so instead I’ve reconstructed what was said from memory. Therefore any errors are my own. If I’ve misquoted or otherwise misrepresented you, please let me know.)

The discussion was hosted by the genial Patrick Shepherd, composer, and editor of the book Artists in Antarctica, published last year: a beautiful big hardback with testimonials and works from artists who have participated in Antarctica New Zealand’s Community Engagement (formerly Artists and Writers) Programme. (Applications open in July.) The artists who took part in the discussion were photographer Anne Noble, painter John Walsh, poet Chris Orsman, painter Margaret Elliot, and (designer? multi-media artist?) Jason O’Hara. All the artists were dressed casually, in jeans and sneakers, except for Margaret, who was wearing a beautiful black and white dress with ammonites and other ancient creatures on it. (Science!)

While they were speaking, images from the book were projected onto the wall behind them, very large. From my eye-line, the names of the artists in the bottom right hand corner were hidden by the foliage of a stage-dressing pot plant, but I came to recognise the work of all the artists on stage: Margaret Elliot’s painted landscapes, John Walsh’s blue-green sets populated with creatures of the imagination, Jason O’Hara’s beautiful underwater photographs, and Anne Noble’s distinctive eye— her white-outs, tractors and piss-poles. As the slides cycled through, Chris Orsman’s poems came up, the same few again and again: I tried to read a few more lines every time.

(Telling second-hand and third-hand stories might seem strange, but I’m passing on these stories because I want to give you precious information. Antarctica! Cool! ((Literally.)) What is it like in Antarctica? These people told me, and now I will tell you.)

I wrote: “The calculus of creative work. Imagination on a shoestring. Where do ideas come from? They arise in the correct conditions. Wild yeast.”

John, I think it was, said how being in Antarctica is like being in a inside-out fridge. The walls are insulated like a fridge’s, but the -40° temperature is outside instead of inside. Patrick told how as you walk along the corridors you have to periodically touch the walls to discharge static electricity, otherwise it builds up to quite a big shock. (When you get home you will find yourself still habitually touching the walls.)

The artists talked about who they went with, their Antarctican buddies as it were. Margaret had been paired with writer Margaret Mahy, who she said was a wonderful, adventurous travelling companion. John Walsh had been paired with Ronnie van Hout— he of Quasi, the self-portrait giant hand with a face on that sits on top of Wellington’s City Gallery.3 John said that he and Ronnie took the piss out of everything together. (Of all the artists, John was the only one with a less than positive take. What he said was that he felt we— humans— didn’t belong there: that the human presence was a polluting influence on the continent. He mentioned the giant tanks of diesel required for transport, and to create warmth— to sustain life— and he said that the fact that powder snow had to be constantly swept from under the buildings proved we weren’t meant to be there. Afterwards, when we were milling around the biscuits, a woman came up and thanked John for keeping it real.)

Later Chris, the poet, riposted by saying that he felt that human presence there rendered Antarctica meaningful, because otherwise there’d be nobody to observe it, to show it to others. That made me think of the Observer effect: observation changes what is observed. There’s no way it could be otherwise. He also said, when asked about what Antarctica had meant to him, that as a poet, he didn’t want to pin things down to a single explanation or meaning. I wrote down this quote from Chris: “Makes a claim by right of vision. An Antarctica of the imagination.”

Chris pointed out that Antarctica is a place with no laws, only agreements. He said that even though there aren’t laws it’s orderly there, no crime—there’s only ever been one murder there. I thought, cynically, Well, yeah, because it’s not a SOCIETY: everyone there has been vetted. The scientists and artists pass through a rigorous process; the military personnel, even if they come from a poor background, are under strict military control. Everyone is fed and cared for. There aren’t any desperate poor people to need to do crimes.

People who overwinter, though, have to watch their mental health: all the jolly skits and handmade newspapers of Scott’s and Amundsen’s parties were meant to ward off the existential horror of the never-ending polar night.

I thought, too, about the surgeon who had to operate on themself whilst overwintering in Antarctica. In my mind it was a female surgeon operating on her own breast— I’m not sure why, maybe because it’s a body part you can see and reach on yourself?— but checking on this, I found it was a Russian surgeon, Leonid Ivanovich Rogozov. He was the only medical professional on a Soviet expedition in 1961. Cut off by polar Winter, he removed his own appendix. (Quote from Rogozov’s journal pre-auto-surgery: “I did not sleep at all last night. It hurts like the devil! A snowstorm whipping through my soul, wailing like a hundred jackals.”)

Jason O’Hara told about penguins: how stinky their colonies are, like nothing you’ve ever smelt. He said that the King penguins reminded him of his youth in Palmerston North. Sorry, he said, if anyone here was from Palmy, but he was about to diss it. There was absolutely nothing to do of a weekend, so the teenagers would wander around the streets moaning ‘I’m SO BORED.’

”But they’d always follow the coolest kid. And the penguins were the same. They’d come and look at you, then turn away like— BORING!… I’m so bored!”

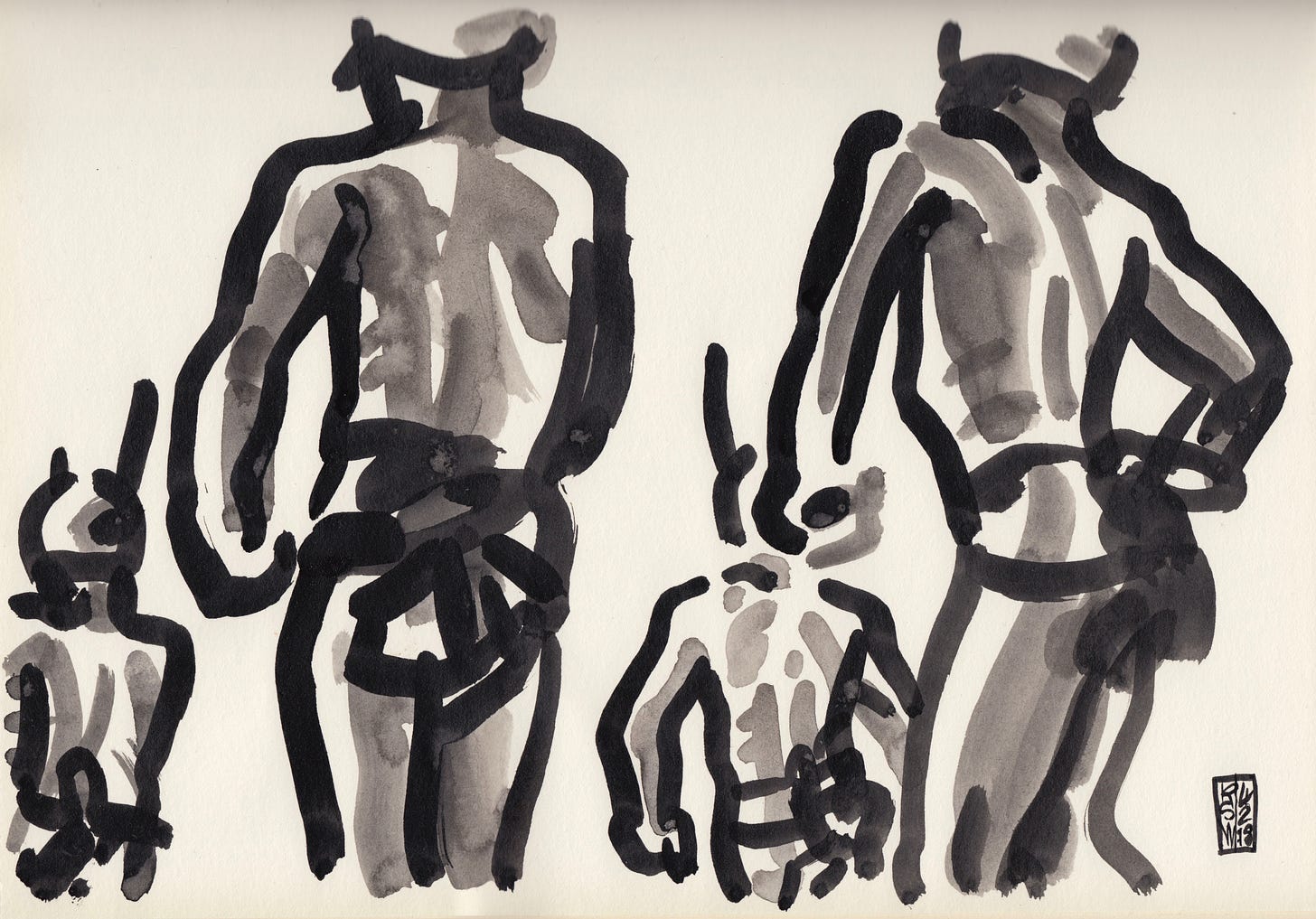

Jason was hanging out with scientists who were diving under the ice. He asked, rhetorically, How can we get people to care about an anemone that lives on the seafloor in Antarctica? He said how the ice could be metres thick but still transparent, letting light through to the water underneath it; but when a foot of snow fell on the ice it blocked out all light, rendering the underwater black. His photos were stunning. Silhouettes of divers against the ice, from below. I saw how the silhouette-form made its way into his re-imaginings, a dancer’s silhouette against blue.

Someone described core drilling, how it’s done in pairs of cores. One ice-core goes into an ice library and the other is available for scientists anywhere to study. Drilling down into deep time. There was this video I’d seen on social media of an ice chip falling down a core-drill hole. It wasn’t this one, but to give you an idea:

Such a freaky sound! My flatmate at the time liked it so much she made it the text message notification on her phone, so I got to hear it a lot of times over.

Anne Noble talked about how Herbert Ponting, the photographer on Scott’s expedition, saw nothingness in the polar plateau— a void— but how she, a fellow photographer, set out to see into that space. She described this as ‘the search for illusory space’: she said “The eye in the mind takes an expectation of knowledge— that is never fulfilled, because there’s nothing to be seen.”

“Antarctica is a mirror,” she said. People see what they bring, they see themselves.

I realised / remembered after a while, as she was talking, that she had been further than the others, into the interior. She had also been more than once, I think: I had come across her Antarctic works before. (It was cool to see her, as I’ve liked her work for ages. She seemed down to earth and also hardcore, with a keen, brave intellect.)

Ponting had a darkroom set up in Antarctica, at Cape Evans.4 He made amazing images; you can see some of them here. I’ve read a fair bit about Scott’s expedition, including Scott’s journals, heartbreaking at the end. Ursula Le Guin was fascinated by Arctic and Antarctic exploration too. She wrote a short story, Sur, imagining a female-only expedition to the South Pole: they get there first but don’t tell anyone about it. She also wrote an essay in 1986, Heroes, in which she defends Scott’s character at a time when it was fashionable to diss him. And she wrote, of course, The Left Hand of Darkness, set on a planet named Winter, heavily influenced by these icy narratives of the quote unquote heroic age.

Anne said that science is represented as objective truth-telling and art as an extra, a nice-to-have, but that art is just as important as science: that it’s the artist’s job to bring a critical mind, to interrogate. She said “Art is often seen as a communications exercise [on behalf of science]. But artists come with questions, just as scientists do.” In her view, artists and scientists were the same, in that they were curious people. “Wherever we have science, we also really need art.”

Anne told a story: she had asked these three scientists what they were studying and they said they were looking at the tiniest creature on the continent, which Anne said was called a terabyte. Anyway, she said the scientists were trying to see “The wingbeat of a terabyte. There’s a poem for you, Chris.” I’m sure terabyte was the word she used— what she said they were studying.5 It sounds like a Borgesian fable. The mating dance of a microparsec. That made me think of

, the microanimist, who proposes worshipping what Siv calls ‘the smalls’. Antarctica is not lifeless, even in the centre, the ice-desert: the life is tiny and deep, under the ice. And at the edge of the continent it is rich, cornucopial. The ice grows a tiny garden, micro-algae photosynthesising the sun: on the seafloor, micro- and macro-algae; seaweeds; plankton, krill, invertebrates; fish, whales, seals; birds.The panel discussed the tricks of distance and perspective on the ice, how it’s hard to tell how big things are, or how close. You might take two hours to walk to something that looks half an hour away.

Anne said “It’s the role of the artist to be cynical— to look another way.”

And “The role of the artist is to look critically at human engagement with place.”

She was talking about her side-project. (“Photographers are curious animals: you can wait for the light, or you can have a side-project.”) When the light wasn’t right, she occupied herself photographing the human-things: the snow-vehicles with women’s names, comedic in their bright colours, an alternative pallette of Antarctica. She said the fact that they have women’s names is a marker of military-ness. Hot Lips. Like the plane that dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, she said— it had a girl’s name, Enola Gay.

I thought how the bomb had a name, too: Little Boy.

Also, Anne photographed the piss-poles. Yellow flags planted in yellow snow, they were just what they looked like.

After the talk Patrick asked if anyone had any questions. I asked what they all dreamed about there, and did they dream now that they were back there? (I was thinking of that passage I opened with, from The Left Hand of Darkness, Genly dreaming he is back on the ice.) John said that he had dreamed of Antarctica very recently— within the last week. Jason said that it never got dark— it was Polar Summer— and he worked himself into exhaustion and then slept like the dead. Anne told a story about being worried about having to get up in the night for a piss. You mustn’t get dehydrated there, because it’s so dry. Anyway, one night it happened, she got up in her tent to pee into the bottle, tripped over her clothes, and pee’d. A nightmare, she said, a nightmare: but the piss froze before it hit the ground. Great! she thought. I can just sweep that up!

Patrick: One becomes very familiar with the exact dimensions of one’s bladder down there. He said, I was always worried I was going to spill my pee-bottle on my tent-mate, because I’m so clumsy. Chris: I remember flying out, carrying everyone’s frozen faeces on my lap.

(The way that in The Left Hand of Darkness,6 when Genly Ai and Estraven are travelling over the ice, it’s a science of inputs and outputs. Estraven can calculate the input— the food, vs. the output— the energy, the work. When rations get lean, Genly is offended that Estraven fasts but makes Genly eat; but as Estraven points out, Genly, the Terran, has not trained in deprivation as Estraven, the Gethenian, has.)

Nobody else had any questions. I’ve noticed lately that audiences seem kind of shell-shocked; the same thing happened at the Lauren Groff interview I went to.

Afterwards in the foyer John said he liked my question about dreams. He said he thought I might be a scientist, studying dreams. I said no, I just thought a place like Antarctica would enter into one’s subconscious.

I had remembered while I was asking, too, how Werner Herzog often asks people what they dream. He does it in Cave of Forgotten Dreams, to an archaeologist who used to be a circus performer. Later on I remembered Herzog made a film about Antarctica. I’d not watched it, but it turns out to be on Youtube:7

Herzog opens by showing people sleeping on the plane from New Zealand to Antarctica, asking in voiceover, “What were their dreams?” Later, A Russian(?) talks about the world dreaming itself. A quarter of the way in it seems to be all about the dreams of Antarcticans. Herzog is with the Americans at McMurdo, who pronounce it An-artica. The bullet-shaped, dancing icebergs as big as countries on the glaciologist’s computer-screen time-lapse animation, the shape and colour of an ultrasound of a baby in the womb. Herzog is forced to flee McMurdo for the frozen wastes due to ‘abominations such as an aerobics studio and yoga classes’. But I’ll pause there. No spoilers.8

(OK, one more: later in the film you get to hear the vocalisations of the Weddell seals, that Jason said leaves whale-song in the dust. As the seal-scientist Regina in the film says, “It sounds like Pink Floyd or something, they don’t sound like mammals and they definitely don’t sound like animals.” Jason talked at some length about the seal-calls— how their songs when rendered as wave-forms are shaped like the Aurora.)

I’d felt a bad feeling, right at the start of the talk, a dumb intergenerational jealousy— how come they get to go to Antarctica, and I don’t? (It’s the chip on my shoulder; it buzzes from time to time.) As the talk progressed, I thought— wait a minute, maybe I could. They did it, and I could do it too. But then again, do I even want to go there? I’m quite fond of being warm, dry, and clean. I’m just an animal, looking for a home.9 Walking around the coast today, pulling my leather gloves on, inter-pushing my fingers to tighten them, I considered how I think of Wellington as pretty damn cold. The cold of Antarctica— minus forty!— is literally unimaginable to my puny body-mind. I thought of how I advise my Auckland whānau not to visit Wellington during Winter, and if they insist I tell them they’re gonna need a big coat, and then when they’re here they say repeatedly, shocked, It’s so cold! I looked at the horizon as I walked. Antarctica is over there. Even the name is a kind of spell, a conjuration.

These artists wanted to see what happened if they put their bodies on the ice. Looking up the Artists and Writers Programme to link to this piece, I found myself at the application page, and I started to really imagine it. (Have they ever had a Wizard before? I guess not.)

I sent the application page to David, who I had heard wanted to go, and he said, ‘You should apply, too.’

“It’s only a fortnight,” said Kelly. “It’s not, like, three months.”

After the talk I caught a bus to Courtenay Place to hear Niko Ne Zna. Streetlights glinting off brass. It was cold. I leaned against a small metal iceberg— a poster-stand. I felt safe there from the panopticon of mindless filming.10 I could hide behind it. It was a tough crowd, small, grudging, passive. But on the compass rose inlaid into the cobbles, two young women were dancing. One was fair, wearing high-waisted bell-bottoms with sailor buttons, and a cropped, fitted top. Her feet were bare, her hair was loose. Her dark-haired friend joined her. They held hands and swung each other wildly, danced in circles, spun over the North, the South. The dark one dropped in and out of the dance, but the fair one kept going, dancing on. She danced as if it were imperative to dance. Bare feet on the cold stone, hair falling and flying. I found her delightful to watch. Her joy gave me joy, and I felt it as a flickering flame, something fragile, precious, something to be protected.

I thought about how these young people had never known an unobserved life. They had grown up being watched, recorded, always, every day— and I thought how that experience was sort of like sex-while-female: consciousness entrained to centre external appearance and performance over experience, over the internal, subjective self. Yes— the Panopticon has a distinctly male-gaze vibe. How could selfhood, that fragile seedling, hope to grow under such a pitiless spotlight? Yet here they were dancing. I thought about being fifteen when I was fifteen and being fifteen now. I couldn’t hope to know what these young folk thought or felt, but I was glad for the spark of spirit that drove this one to so defiantly dance her joy.

And I thought, too, about how something unseen, untouched, is sacred. Like the interior of Antarctica, the peak of Everest. Sometimes the most reverent thing we can do is to leave a thing alone. Antarctica, virginity, whiteness, purity, land as female, conquering, subduing, deflowering— I don’t mean any of those bullshit associations. What do I mean? I mean that innocence is sacred, actually. Maybe it’s not only that everything is recorded and seen; it is also that being made to see everything is a fall from grace. For a child to see horrors that can’t be unseen is a premature fledging, and after that there’s no way back to the nest. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned.11

This morning I dreamed that my smallest orchid (the one that got accidentally half-frozen when someone switched the heat-pump off) was making a flower. I looked at it in my dream, and saw that it was pushing out the ‘mitten-shaped’ flower shoot, a chunky green arm reaching. I was surprised, because it’s the tiniest of all my orchids, and I would have guessed the biggest one, that I call ‘Big Boy’, would be the likeliest to flower. Look! I said in my dream, carrying it over to show Kev.

(Could it be that this dream is literally my smallest orchid expressing a desire for tropical humidity— though it has never spoken up in my dreams before? I have had my orchids for less than a year, so they haven’t bloomed, but I have researched their flowering: it happens in Winter. It feels like a lot to hope for. Maddy once told me, “When my Phalaenopsis flowers, I feel like a magician.”)

So… I just went and moved my three middle-sized orchids to the windowsill for some light, and had a close look at them while I was at it. And— look!

This is the very first orchid, the one I found in the skip still wearing its yellow gift-wrap: thrown away because it had finished flowering. Maybe this will turn out to be a root, but I reckon it’ll be a flower spike.12

Last night at the Long Table I took part in a five-minute-poem-writing exercise with Andy Jukes. We were read four poems to respond to. The first was the ancient nursery rhyme Who Killed Cock Robin? Another concerned refugees.13 Then we had five minutes to write a response. This was my poem:

When the centre falls out

We all have our tasks,

Bell, pull, pall.

You bind the jaw,

I weigh the eyes.

You can see by the eyes, says Andy,

When someone has died.

You close the lids and send them downstairs.

So many tasks!

Once the tāngi14 is done,

The guests must clean,

Iron the sheets.

There must be a reason for it,

Says my sister.

At dinner Abdul starts talking and can’t stop.

The Taliban man got sick of our crying,

Took his Kalashnikov and shot

My brother’s toe off.

This stream of requirements

For staying alive!

P.S. Coming home from the pub just now in a merry mood, I thought I’d take a closer look at the tiniest orchid, the one that appeared in my dream telling me it wanted to flower. Sure enough, under the leaves, the tiniest little green bud is pushing through.

Not-the-land-of-bears

At some point the w and the h swapped places in the word whale. I have read convincing theories that this combination of sounds references a whale’s breath. This wh is also, of course, how my surname begins, and my surname is also from the Old English: wægn-wyhrta, a wainwright. Way and wain / wagon are etymologically linked, too.

Tangentially, here is a dictionary of nautical terms in English that have Anglo-Saxon origins:

https://historyundusted.wordpress.com/2013/10/05/nautical-terms-with-anglo-saxon-origins/

I became interested in Old English through reading the excellent book The Wordhord, by Hana Videen.

But not for much longer: in looking it up, I see it’s due to be taken down this month.

There was an article in the Sunday Star-Times today about how Evans was possibly the cause of Scott’s party dying as they returned from the Pole: the theory goes that Evans ate more than his fair share of the rations from the depots on the way back, leaving Scott’s party to starve. (Another theory I have heard was that the ration calculations became inadequate when Scott added another member to the Polar party at the last minute.)

Maybe a tardigrade?

If you have never read this book, please read it. It can be confusing at first— the narrative voice switches between different characters and times— but please, stick with it. I remember it didn’t make sense to me until I had read it twice, then it began to open to me like a flower.

I also found this, from three months back. Content warning: it has Piers Morgan in it obvs, but Herzog outwits and outclasses him without even trying.

Morgan: ‘So your Dad was a Nazi, how did that affect you?’

Herzog: ‘My Mum was a Nazi too, but NBD bro, everyone’s parents were Nazis.’

Penguin

Home is where I want to be, but I guess I’m already there…

It was particularly the mindlessness of it that bothered me, the way that every passerby who stumbled upon this fun thing, an eight-piece brass band on a Winter’s night street, automatically lifted their phone in front of their face. I thought, too— having been on the other side of the fence at my gig last weekend— about how it must feel to the band, too, when instead of faces looking back, they face a wall of devices. Something is lost, the dynamic interchange of energy, the human-to-human-ness.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto

It was the first two parts of this three-part poem by Nikolai Duffy:

Funeral

“I weigh the eyes…” such a moment of synesthesia with this line. What a wonderful poem altogether….

Many years ago when my wee girl was in primary school, she had a class called ‘science and poetry.’ Unheard of in a poor neighborhood school. She learned to write beautiful Haiku…

The sound of the ice slab dropping down the bore hole is redolent of the sounds from the ‘shoot ‘em ups’ in the “Westerns” my grandad watched—the way they ricochet around a dusty canyon. If you decide to avoid the -40 temps but want a riveting read of derring do in Antarctica… I recommend: “An Unsung Hero

Tom Crean - Antarctic Survivor” by Michael Smith.

Thanks so much for your field notes on the field notes! Much better to read about your listening to people than to actually go to Antarctica, for me anyway (of the better-to-not-go variety of love for the place). Also interesting that nobody else had any questions + the overall phenomenon of the shell-shocked audience. Is there something going on in the class dynamics of these occasions (people not feeling part of a rarefied/funded artist class and not feeling safe enough to speak)? Or is it more of a consumption model (here to get my ticket's worth/vampirise some culture before getting back to my real life)? Two very cynical interpretations, but much more to think about! Anyway, welcome to the little orchid bud x