William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “As I was walking among the fires of Hell, delighted with the enjoyments of Genius, which to Angels look like torment and insanity, I collected some of their proverbs, thinking that as the sayings used in a nation mark its character, so the proverbs of Hell show the nature of infernal wisdom better than any description of buildings or garments.

When I came home, on the abyss of the five senses, where a flat-sided steep frowns over the present world, I saw a mighty Devil folded in black clouds hovering on the sides of the rock; with corroding fires he wrote the following sentence now perceived by the minds of men, and read by them on earth:—

‘How do you know but every bird that cuts the airy way

Is an immense world of delight, closed by your senses five?”

I came home dirty from a day of renovation, washed the plaster-dust out of my hair and put on a clean dress. The evening light was so sweet, and the air so still, that I thought I’d go down to the beach.

It was the first time in a long time that I’d been drawn down to the sea, lured by beauty, rather than beach-walking out of obligation or desperation. Besides the relentless winds of Spring, I’d found almost nothing for so long that I’d given up on beach-combing. This is the sum of my findings for the last few months, one or two pieces per walk:

So I wasn’t expecting much, but it felt good to be outside. It finally felt like Summer. There were plump wet children joyfully shrieking and splashing in the water while their parents reclined side by side on the pebbles, like seals. The light was going golden, so that it felt like a benevolent liquid medium. Instead of turning right to the stream-mouth, like I’ve been doing through the lean months,1 I went left: my old way.

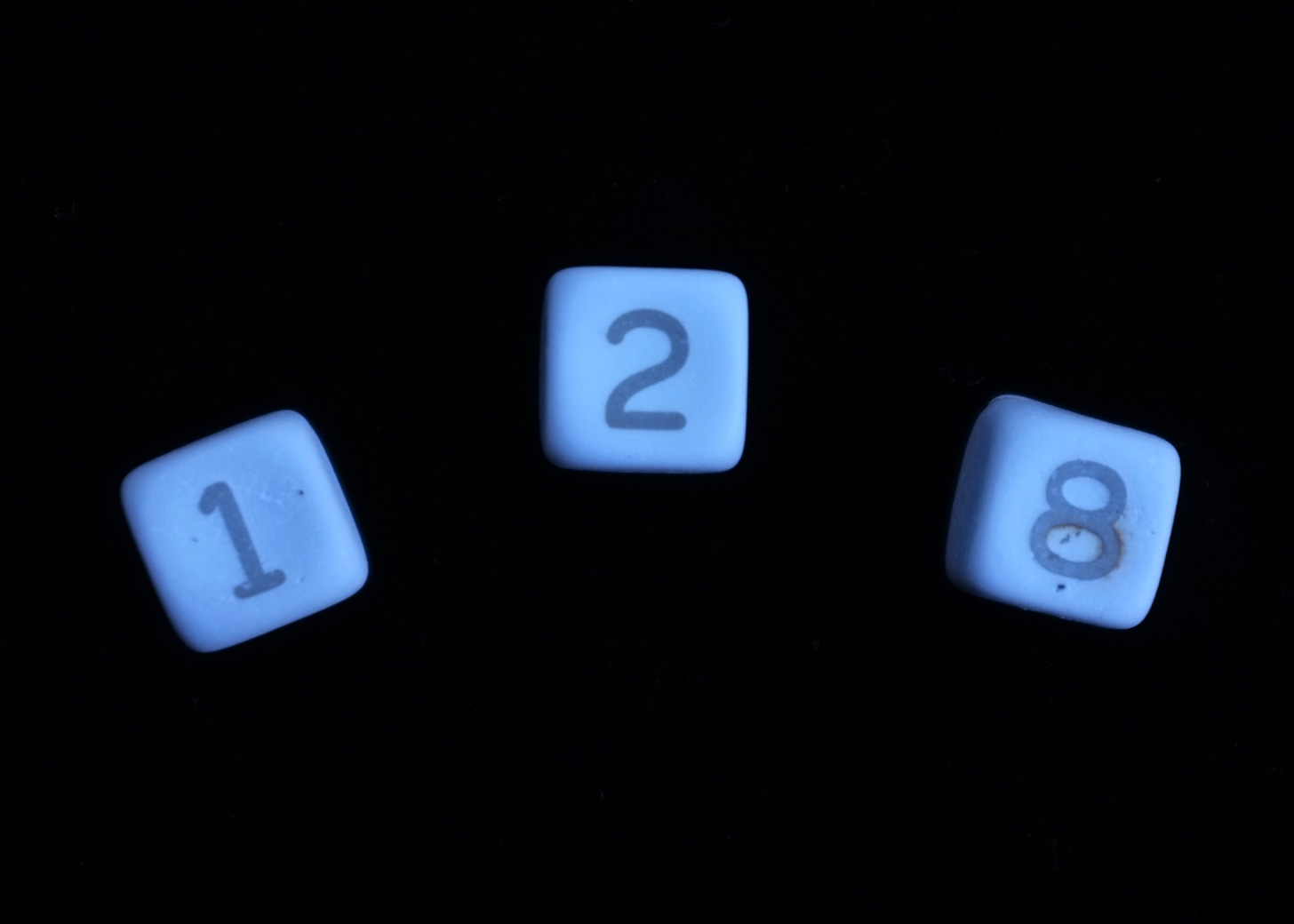

Lying in the wrack between the rocks I saw a small square key: an orphan button. I picked it up with great anticipation— number 2. High Priestess, said my Tarot-brain, Holy of Holies, Sanctum Sanctorum, and that made me think about the William Blake biography I’m reading, William Blake vs The World, by John Higgs. Higgs explains that Jerusalem is the city that contains the dwelling-place of God;2 Babylon is all the places that don’t. He says that the poem now known as Jerusalem is from a preface3 to Blake’s book about Milton, written during the only time Blake and his wife Catherine lived outside of London— in Felpham, Sussex: green and pleasant land.

Higgs: “In the preface, Blake does not waste time warming up before delivering his opinions. It starts as a full-on rant… [and] very quickly becomes a rabble-rousing rallying cry to all those who want to overthrow the insipid, uninspired establishment of Britain, and replace it with the inspired and the brilliant:

’Rouze up O Young Men of the New Age! set your foreheads against the ignorant Hirelings! For we have Hirelings in the Camp, the Court, & the University[…] We do not want either Greek or Roman Models if we are but just & true to our own Imaginations, those Worlds of Eternity in which we shall live for ever…”

Then Blake goes into verse. Jerusalem emerges: And did those feet in ancient time etc.

Higgs: “It is hard now to separate those words from the stirring, patriotic music that Sir Hubert Parry composed in 1916, while the First World War raged on. That this hymn is a favourite of English public schools is one of the great ironies of the William Blake story, because in the context of the preface it is basically a demand that such institutions be overthrown.”4

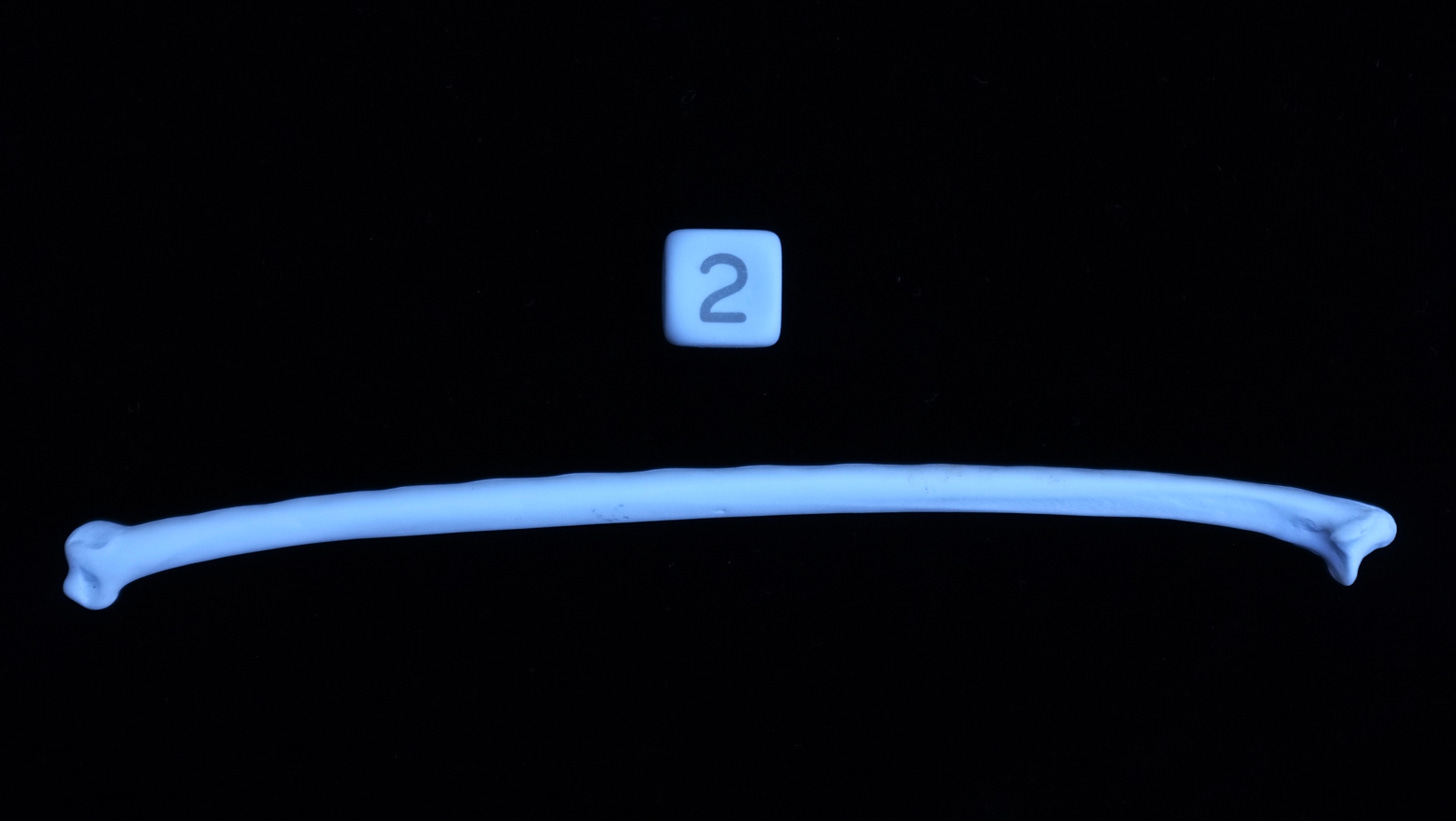

A few steps along I found this bird bone, a seagull’s wing-bone. (Ulna? Radius? I think ulna.) I picked it up for its clean economy of beauty.

(Even better, the number 2 makes a set— it’s from a keypad I’ve found keys of before.)

I walked along weighing the delicate bone in my hand and thinking about the paradox of a bone that flies— further, a bone that enables flight. Nature’s engineering marvel. Inside a bird’s bone are distinctive honeycombs, like chewing gum stretched wall to wall. (This was how the moa was first discovered by the Western world, extrapolated from a chunk of thigh-bone. Te Ara says “In the early 1830s the trader John W. Harris acquired a 15-centimetre bone fragment. In February 1837 he gave it to a Sydney surgeon, John Rule, with a note that it was from a giant bird called a ‘movie’. Rule took the bone to England, where it was examined by the naturalist Richard Owen in 1839. The following year, Owen proclaimed it to be the femur of a bird, ‘nearly, if not quite, equal in size to an ostrich.”)5

I was thinking, too, about the Zoom call I was on the other day. Watching Dougald speaking, his high forehead outlined against his dark hair, I suddenly saw his skull’s vaulted curve inside the skin. Looking down at his eyes, I could see the bone-forms under those, too: the eye sockets, the cheekbones. Then looking at his speaking mouth inside his beard, that wet doorway into the head, I thought how strange it is that teeth are bones, that we reveal our skulls every time we open our mouths. Once I held a human skull in my hand, and it felt just like cradling the back of someone’s head— because it was.

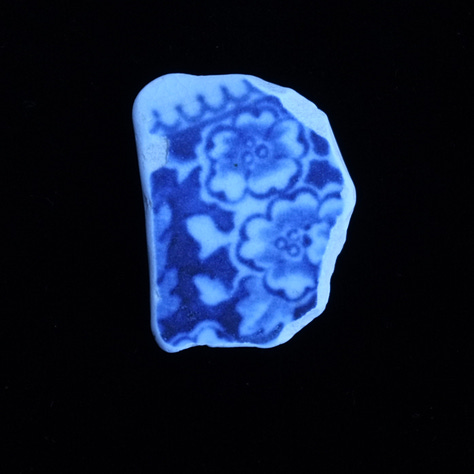

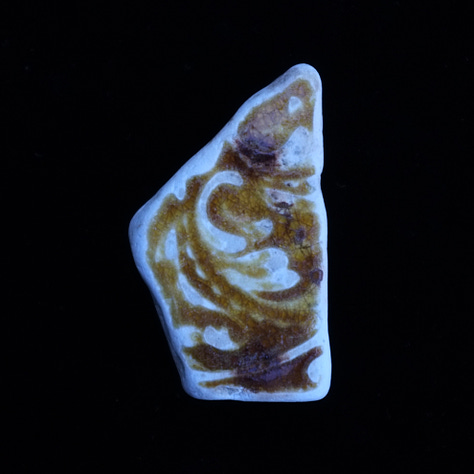

I walked creekwards, passing between the frisking children and their parents. I could feel that the ground was alive again, that the finding-tide had changed. The ceramic fragments I turned over revealed their bright skins.

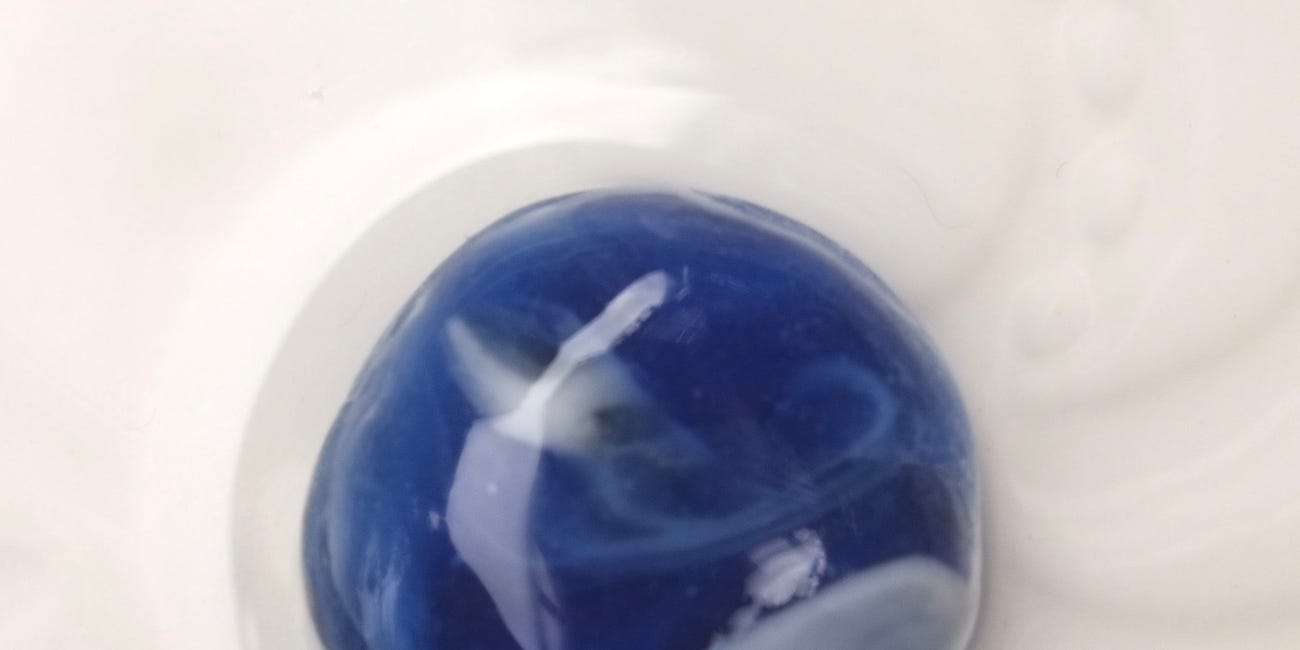

I found a blob of glass that I almost left— it was mostly white— but decided to keep. (I was in a mood for keeping, after the barren months. Also, one never knows what resonances are still to come: for this same reason, if I leave stuff I’m ambivalent about leaving, I put it somewhere obvious— on a big rock, or a log, so I can find it again if I come across its twin later in the walk.)

This is also part of a set— glassblower’s snipped-off globs— that I wrote about here:

Beach-Combing Journal: Globs and Prunts

Overcast sky. Diagonal shadow-stripes of rain at the horizon. I walked down to the sea and saw this shining in the wet pebbles. Flat on both faces, it’s the nipped-off end of a glass-blower’s molten glasswork. (The hot glass can be snipped with metal shears.)

A man and a woman were walking their matched pair of dogs (a lapdog-looking breed, pretty dogs, one black, one brown) by the creek. The woman said to me “Did you find anything good?”

I opened my hand to show her. “That one looks like a frog.” she said. It was true: it DID look like a frog. I wouldn’t have noticed, seeing only tree; I’d failed the simplest Blakean test.

“Is your name Rosie?”

”Yes,” I said, thinking she must have seen me in the newspaper.

Woman: ”I rang you up once asking if you needed flatmates, and you told me it depended how young they were. They ended up moving in with us, and you were right, they were too young. One of them did things like cooking steak in a biscuit tin in the oven and stinking the house out.”

She considered me. “You’re some kind of a hippie, aren’t you.”

I stared at her. “No.”

Suddenly self-conscious, loose long dress, long hair out to dry.6

As we talked I was itching to get back to finding. The light was starting to change. Politeness held me upright. I did like her face, though: beautiful eyes and confiding friendliness. She stood at the stream’s edge beside a log that had been laid across. The water was running over the middle of the log. She was telling me how the Government had tried to kill her because she knows too much, by prescribing her two kinds of antibiotics that should never be mixed. Her husband was sitting patiently on a rock further up the beach. She kept putting her sneakered foot onto the log then back onto the ground. Eventually I said did she want me to hold her hand so she could cross? I had my tall gumboots on so my feet wouldn’t get wet. She put her small hand in mine and I escorted her across the log bridge like some knight. In mid-stream I looked down and saw a piece of ceramic through the flowing water. After she had gone on, I went back for it.

Here is everything I found:

Apophenia is a newish word, coined in 1958, meaning the tendency to perceive a connection or meaningful pattern between unrelated or random things (such as objects or ideas). Pareidolia, the human tendency to see faces in things, is an example. For a while I used ‘Hedge Apophenist’7 as a self-descriptor. Then I worked out that apophenia’s main meaning is as a symptom of mental illness, and it suddenly seemed weird rather than wyrd to use the word on myself.

Blake saw angels and demons and conversed with spirits of the dead: in his telling, he literally saw and spoke to these beings. Higgs: “What made Blake so fascinating was the casual way he talked about the spirit world… Somehow, he did this in a way people found endearing rather than disturbing. As [Henry Crabb] Robinson8 wrote, ‘There is a natural sweetness and gentility about Blake which are delightful. And when he is not referring to his Visions he talks sensibly and acutely.”

Who’s to say which acts of imagination are right and which are wrong? The harmony between objects, the way ideas sing to each other, offer ways of weaving meaning from the world’s chaos. Even words are one step removed from the real. How are we to apprehend reality if not through the instrument of our own particular body?

Caroline Ross, at the Long Table on Monday, described clearing a well of rubble. The well in question is outside her family’s Dorset fishing huts. “It doesn’t have a holy name, and it isn’t dedicated to anyone special.”

The well was full of rubbish, “Rubble, glass, and gubbins.”

One day she was moved to clean it. “I‘ve noticed in my life that if I follow these deep urges to do with nature, something goes well.”

Crocs, rubber gloves, combat trousers; moving stones all day, then, the next day, sweeping the mud with a brush. “I felt like some weird sort of Zen cleaning lady… By the end of the day there was clear water, and I was just really happy, and the blackbirds were coming down, and it was all good.”

Suddenly an old lady appeared “with a classic South Coast massive tan and really thick black mascara,” and told Caroline that she used to get water from the well in the 1950s: “I used to do that, but I can’t since my hysterectomy… That’s the only water around here always flowing, glad to see you’re doing that, thanks love, thanks, bye!”

Caroline: ”And the hairs on the back of my neck stood up. I grew up really liking Pre-Raphaelite paintings, and all the nymphs have got like long flowing hair and great robes, and all the well-tend-keepers are sort of Celtic beauties, they’re not women with bleach-blonde hair wearing combats and Crocs, and I realised that holy tasks— sacred tasks— don’t come with tiaras and goblets; they’re like oversharing Dorset women telling you, crack on.”

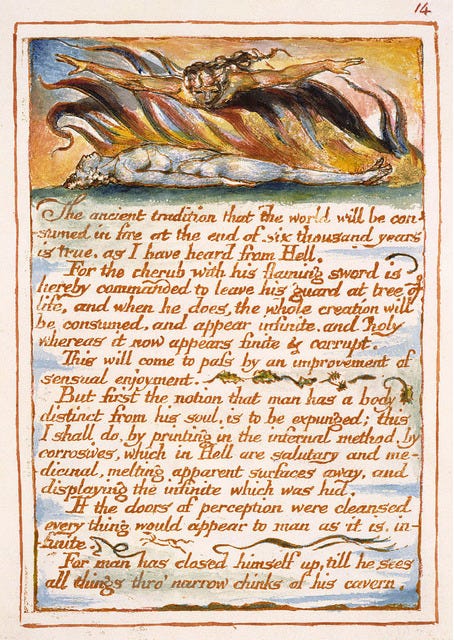

Looking for a way to end. Ending is tricky. Doesn’t a stream flow on and on, doesn’t a spring? Well, I must just draw up and pour out this bucketful. Back around the lip of the bucket to Blake, who says, further on in the same book, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “I shall… [print] in the infernal method by corrosives, which in Hell are salutary and medicinal, melting apparent surfaces away, and displaying the infinite which was hid.

If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.”9

The stream is likeliest for finding when things are static because it’s the most dynamic part of the beach, in the sense that the channel often moves around even when the sea doesn’t, uncovering new drifts. Also, the stream brings things down from the Dump.

i.e. the Sanctum Sanctorum, the innermost temple the Priestess guards in the Tarot card: that which can’t be known.

(The Internet informs me that in the Marvel Universe, the Sanctum Sanctorum is a three-story townhouse located at 177A Bleecker Street— the home of Doctor Strange. One can build it out of Lego.)

Later discarded. Higgs: “Perhaps Blake found it, with hindsight, too hectoring and political.”

Higgs: “The ‘dark Satanic Mills’… are sometimes said to refer to Oxford and Cambridge, the great universities of the age that were churning out constrained, uninspired minds blind to the divine nature of human imagination… Satan himself is ‘Prince of the Starry Wheels’ and ‘The Miller of Eternity’, grinding time and space into their constituent parts. The fine particles of dust produced are separate, broken and have lost their spiritual component. It is these Starry Mills of Satan that generate the ‘Single Vision & Newtons sleep’ that drive the Age of Enlightenment.”

Owen was a complete bastard, by all accounts. I highly recommend Quinn Berentson’s excellent and comprehensive book, Moa: The Life and Death of New Zealand’s Legendary Bird.

I was at a book launch the other week when someone told me how long my hair was. A woman sitting nearby: “It’s weird when people say that, isn’t it? Like it’s news to you that your hair’s so long. Like, Oh, wow, I hadn’t noticed. Thanks for pointing that out.”

She delivered this sarcastic observation in a benevolent tone, and besides, she was right: commenting on obvious aspects of other people’s appearance is a dead-end street of conversation, like when you give your child a weird name and doom them to the same dumb exchange for their entire lives.

I was fascinated by this woman’s vibe. She was very self-possessed; she seemed like some sort of a wizard. The layout of dinner meant we didn’t get to talk. Later someone said to me “That was Taika Waititi’s Mum.”

Hedge, meaning wild, wandering, not of any school— like a hedge witch or a hedge priest.

They met at a party. Robinson wrote about it in his journal.

I recently re-read Just Kids by Patti Smith. In it she describes Robert Mapplethorpe— they are both young and penniless on New York— stealing an original Blake etching from the auction house he is working at: a place he despises. He steals it on impulse, shoving it down his trouser leg, but towards the end of the day becomes paranoid that he will be busted, shreds the etching into pieces and flushes the pieces down the toilet. He comes home and tells Patti what he has done. They are both horrified at the enormity of the act but agree that better nobody should have it, than someone else— other than them— having it. (I’m paraphrasing from memory as I’ve already returned the book to the library.)

Gosh I love your beach combing finds. Magic.