Beach-Combing Journal: There & Back Again

Walking around the corner at Makara

This piece contains a lot of images: it will get cropped, so click through from email and read it on Substack.

Robert Macfarlane, The Old Ways: “The compact between writing and walking is almost as old as literature— a walk is only a step away from a story, and every path tells.”

A sunny Sunday. Some of us had been drinking wine the night before, and all of us had been watching a movie about Thomas Fraser (the country-singing creelman of Burra) until late, so we slept in, forgetting we were meant to go to the Cathedral and sing sea shanties. (Something to do with the Mission to Seafarers, which made me think of that scene in Moby Dick: the tiny Nantucket whalers’ chapel, the old preacher climbing the ladder to the ship-shaped pulpit and preaching on Jonah.1 I’m sure it wasn’t anything like that, though— likely more Anglican— cups of tea and biscuits.)

Anyway, because we were jilted (by our own sin and sloth) of the chance to showboat in the biggest church in town, I was restless. Itchy feet. Also, I thought about my writer’s block and what

says— Solvitur ambulando (It is solved by walking). Two birds, one stone. Let’s go to Makara. Last time I was there, I think, was the time I found the argonaut shell tucked into the driftwood log. That was in Summer. I remember how scorching the sun was that day, how I tried to hide from it under my scarf. Even though it’s Winter now, the sun still has that same pitiless quality on the coast. I reckon it has to do with the treelessness: there’s nowhere to hide except the occasional rock-crack.

Because it was a sunny Sunday Makara was crawling with people. At the edge of the carpark I saw a fetching little puppy on a lead, which I went and patted. Even though it was very young, it had good manners: it didn’t do the mad jumping, licking, and biting, but sat by my knee and licked my hand a bit as I stroked its beautiful little head, all fine skull and silky ears. Right by the carpark was a man fishing with his poles stuck into the beach-pebbles, and a woman lying on a blanket by the open boot of their car, singing karaoke to nobody in particular. She had a phone in one hand and a microphone in the other, and a small amplifier resting on the blanket beside her. She was singing a pop song I didn’t recognise, which was just coming to the climactic high bit. She gave us a dazzling smile as we passed.

There were wooden boxes beside the path with a big white kiwi footprint on them: stoat traps of the Capital Kiwi Project. These kiwi live on one side of the island’s South-West corner and I live on the other, but there are 65 of them now, and there’s nothing but a whole lot of near-empty land between our ‘hoods— I’m confident that eventually an intrepid one will make its way across to my hills. In November last year, it was discovered that two kiwi chicks had been hatched by the cohort of kiwi released the year before: the first wild-born kiwi in Wellington for 150 years.

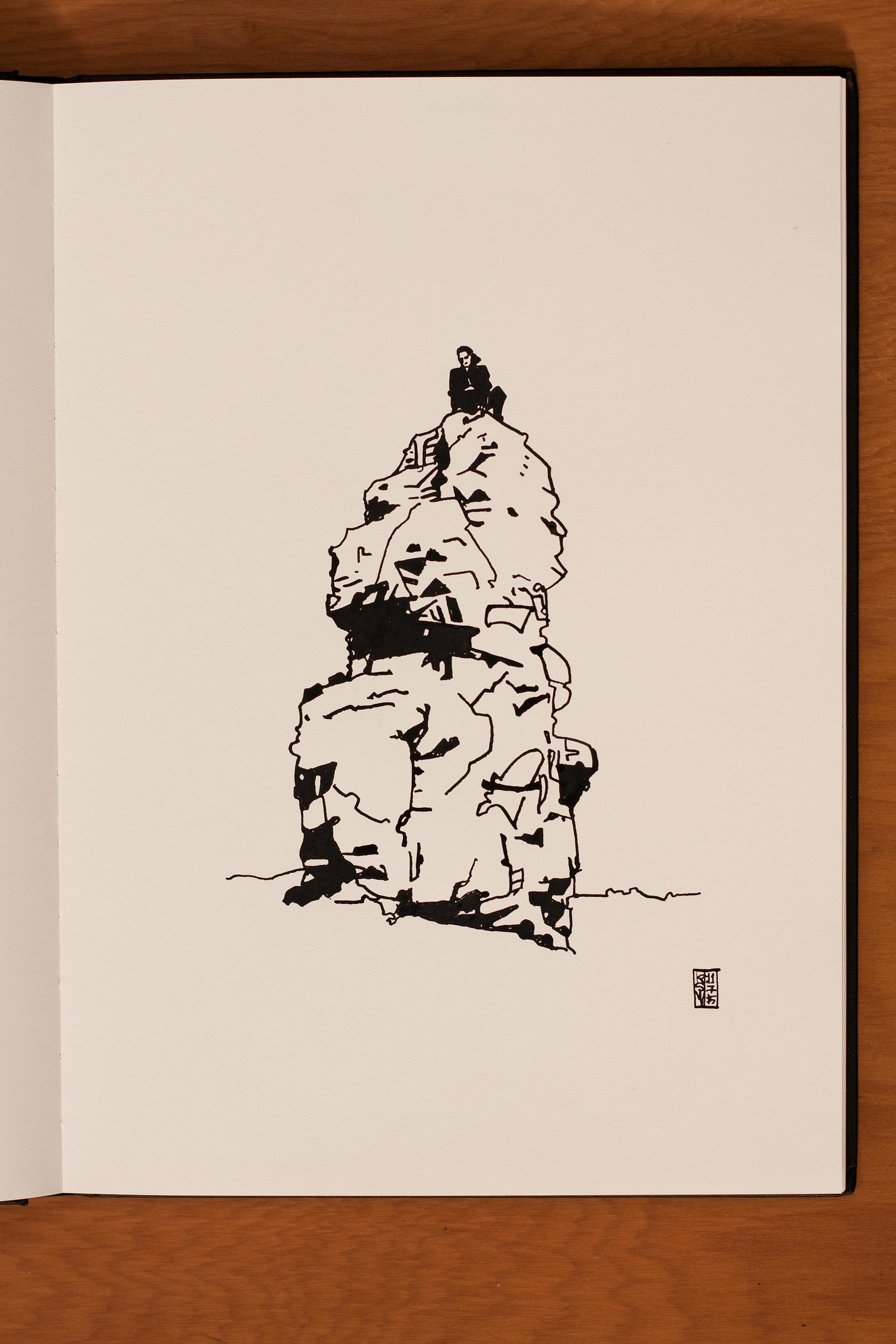

When we came to the first point, I remembered that I had once climbed the rock that looks like an ape’s head. It was very windy, and I was with my old flatmate Johnny Smoke, who was scared I was going to fall. I remember I was annoyed because I had already decided I could do it, and I felt he was jinxing me by voicing his fears— you have to hold your nerve when you’re climbing things. Also, for some reason, I was wearing blue overalls;2 I think because the weather was colder than we expected, and the overalls were the only spare garment in the car.

Out beyond the head-shaped monolith were two fisherfolk, casting from the spit of rocks that projects out into the sea. Kev said it was a prime fishing spot that people fight over. “I mean… Maybe not literal punch-ups, but it’s hotly contested.”

I wasn’t walking to comb, nor did I have my camera with me, thinking I could borrow Kev’s phone if I needed to, nor was I thinking about writing— it was a constitutional. But in recalling the walk now, I see that remembering along a narrow path is easy. It’s a single narrative thread: you just re-walk the path in your mind and what happened arises in sequence. (What happened this time, and also what happened other times.) When I was a kid I had this book about Coyote, folded stapled photocopied pages with the cover missing. The stories were an old man talking, and a lot of the stories went like ‘Then Coyote walked down the road a bit more, and…’

That book wore a path in my mind; I wish I had it now.

The coastal tracks wind their way between sea and steep hill, foot-roads as old as human habitation. They have that feeling of an absolutely logical way to walk, and it is easy to imagine people travelling that way for days, stopping to gather kaimoana3 and cook over driftwood fires. (You know that the blackened wood you see is half-charred from recent fires, but it also feels like centuries ago.)4 As we walked Kev was on fishing reconnaissance. He said it would be good to stay the night and fish in the morning, and I could easily imagine it, on a sweet day like this— how easy it would be to just not go home. There are piles and piles of driftwood, you’d not even have to walk to collect it. Just make a fire and recline by it as the sky fills with stars. The open night for a roof, until pink dawn.

Everyone we passed on the path greeted us, and we greeted them. Families, dog-walkers, young people in pairs, serious trampers with walking poles. There was a woman and a man— the man was pushing a black wheelbarrow— going the same way as us. Kev said “Going adventuring?”

”Diving!” said the man. He was pushing all their gear in the barrow.

(In Margaret Mahy’s book The Man Whose Mother Was a Pirate, the timid office clerk pushes his piratical Mother to the sea in a wheelbarrow, and I have an image, too, of someone pushing their mermaid wife in a wheelbarrow.)5

We came to the place where the track splits off up the hill. There’s a set of rusted metal rails going down into the sea there, and a rusted metal winch: someone used to seriously launch a boat here, where the water’s deep. Kev thought this indicated we were in what they call Fisherman’s Bay, though it wasn’t marked on the map at the start of the track. Up, or around? We decided to keep going round. The hill-path means a lot of climbing of steep paddocks to get to any view, and there’s more to be found at sea level. Once we were walking we got our walk on. What’s around the next corner? That question carries you forward. I was tempted by the drifts of seaweed but it made more sense to look at them on the way back— less far to carry things. I saw a few of these small seabirds, all of the same vintage. They probably all got caught in a storm.

(Looking at the bill, I thought it was some sort of prion, but I included it in my email to NZ Birds Online ((see below)) and Colin Miskelly— the vertebrate curator at Te Papa— emailed me back saying it’s a sooty shearwater / tītī: “They depart for the northern hemisphere in May, and so it has likely been dead a couple of months. Prions are much smaller (their body weight is less typically than 150g, compared to about 800g for a sooty shearwater) and they are bluish above and white below.”) I see: it does look sooty. Tītī are a traditional food down South. The young birds are taken from their burrows and preserved in their own fat in bull-kelp pouches.6 They are still harvested around Rakiura / Stewart Island. The kupu Ingarihi7 is muttonbird. When I stayed in the cottage on Ihumoana Island, at Te Henga, the tītī would crash-land into the foliage at dusk. Some had burrows, but some nested under the cottage, and you could hear the chicks calling out to their parents as they landed, feed me, feed me, and later you could hear the parents crooning to their chicks under the floorboards.

We came to this enormous log, which Kev pointed out had been cut by someone wielding a 24-inch chainsaw: they hadn’t been able to reach the centre of the trunk with their saw.8 “What do you reckon it is?” I said. “Macrocarpa?"

We were two bays deep now. When we came to the next point, the path disappeared into a jumble of boulders. I stepped across a beautiful rock-pool fringed in pink coralline algae: I wanted to take a photo, but didn’t. If I’d had my camera, I would have. These rock-pools have an ultra-femme vibe that I find very fetching. (Pink frills fringing a wet slit, yes— but it’s the true weird, the fluxy, salty feminine of the intertidal zone.) Rock-hopping to get round, we saw the divers getting into their wetsuits, with a spear-gun leaning against the rock. Kev asked them what kinds of fish they usually saw here, and the man said “Mostly butterfish.”

Past the boulders, it started to feel properly wild. The path disappeared, and we were walking on stones that were round as eggs. During lockdown Kev went through a phase of making fishing weights out of round stones macraméd in knotted cord that he called stonkers:9 this beach was stonker city. Given enough time one could probably even find that holy grail of finding, a perfectly spherical rock.

As we walked along over the top of these round stones, they clinked together underfoot in a resonant lithic music. Kev said that he could smell something— a dead seal? Nah, I said: dead seals are the stinkiest thing there is, surpassed only by rotten shark. A few steps later, we saw what it was— an enormous dead bird.

I guessed that it was a mollymawk or albatross. Having learnt my lesson from the giant petrel a few weeks back, I checked its legs for bands: none. The albatross was not desiccated— there were still flies at work— but it didn’t smell too bad. I took a close-up photo of its beak, so I could ID it later.

(When I got home I looked it up in my bird book. To my surprise the black edge to the upper mandible suggested it was a toroa, a royal albatross: a huge, legendary bird, with a three-metre wingspan. I don’t think I’ve ever seen one before. I put the photos on the Internet to see if any of my friends could positively ID. Three or four people said it looked like a royal, and my friend Don suggested emailing NZ Birds Online. Colin Miskelly, as I mentioned above, emailed back: “The albatross is probably a northern royal albatross, though it is hard to be 100% sure without seeing all of the upperwing10 (which would be all-black for northern royal albatross, which appears to be the case based on your first image).

The bird does have a dark cutting edge to the bill, though this appears to have faded after death.”

The next day Finn messaged me asking what I was going to do with the bones. I said that the albatross was very large and only half-rotten, so I’d left it there.11 Finn said the leg-bones are good for making kōauau.)

We determined to get to the true point, so we could see the landscape unfold, the next big bay. Neither of us had ever been that far before, so we didn’t know how far it was. We just had to keep walking and find out. It was a perfectly clear day. The vantage was different from my home Coast, which faces South, overlooking the left-hand end of Te Wai Pounamu, the South Island; Makara is ‘around the corner’, facing West, so we could see the right-hand end of the South Island— the Marlborough Sounds— D’Urville and Stephens Islands.12 And looking Northward up the coast, Mana and Kāpiti Islands lined up one behind the other.

The further we got from the beaten track— though it was still pretty beaten, there were people walking by still, and signs they had been there13— the more wild and finderly things felt. I was thinking about the moa bone my friend Reuben found a month or so back, weathering out of a clay bank:

Out to sea I could see a bird sitting on a rock that didn’t look like a gull. I kept staring hard at it, squinting against the dazzle, trying to see what it was. I wished I had my spotting scope. It had a pointy face, and I thought it might be a Caspian tern. They’re enormous— for a tern— and their call is a dinosaurish croak, kind of like how you imagine a small pterodactyl might sound. Just as we came to the true corner, and the big bay unfolded in front of us, the huge white vanes of the wind turbines slicing the air above the hill, the bird flew past and I saw that it was, indeed, a Caspian tern. We stepped into a flow of cool breeze that felt good, like drinking water. There was a gannet flying in high circles over the dazzling sun-path. I watched it for a while, but it never dived. I sat down on a log and tried to talk to the birds with my karanga manu:14 they more or less ignored me. We took some selfies that weirdly turned my eyes bright blue, as if I’d been ingesting the Spice.

On the way back, I felt freer to dawdle. The Caspian tern flew past again, followed by a less sleek Caspian tern calling to it— parent and child. I climbed up amongst the driftwood piles. I had two objectives. Small, fetchingly weathered pieces with a flat surface to draw on:

And gnarly chunks for mounting staghorn ferns:

It’s harder than you might think to find driftwood to spec. I saw a good one half-buried and pulled it out. It was dense and heavy (a root?), complex in form. I couldn’t see a natural mounting-point, but it was of a carryable size, too good to leave behind. I threw it down to Kev.

We kept trudging back the way we’d come. I was trailing behind now, sorting through the wood with my eyes. My beach-pace can be glacial if I’m properly looking, but this wasn’t that. More of a slow walk, a not-stride. I saw this one:

It had a perfect fist-sized hole15 to tuck a plant into, and a flat surface along the bottom, meaning it would sit on a windowsill. Even better, it was left-handed, meaning it would likely sit on the other end of my bathroom windowsill and make a pair with my first staghorn.

The sun was bright white off the mirror of the sea. I said that the whales must pass by here on their way North, and if it was calm like this, you’d see them clear as anything. (It rarely is, though.)

When we got to the boulder-hop the divers were out of the water. “What did you see under there?” I asked the woman.

She told me she’d seen a huge stingray that freaked her out so much she jumped straight out of the water and wouldn’t get back in. It was her first time diving there. The same thing happened to me once when I was snorkelling. I was swimming through a narrow rock-channel near the boat-ramp when suddenly a massive stingray appeared just under me, travelling the other way. Neither of us could turn around, so I stopped kicking, stayed very still and let it pass under. It frightened me and I immediately got out, too. It’s the SIZE thing— a big wild animal, very close. More than that, it’s a reminder that under-the-sea is an alien environment, filled with weird denizens. (That’s also what makes it so amazing.) Part of the weirdness of being under-the-sea is the three-dimensionality, or the reversal of dimensionality: where we land-dwellers look around and up, under-the-sea one looks around and down, and that depth, the way light (and with it sight) disappears into the dark below— the understanding that this bit of sea is joined to the abyss, and that creatures can just appear from any direction— that can be profoundly unsettling for land-dwellers. Stingrays are actually quite chill (even friendly) unless you stand on them or hook them, but they can sting you if they want to.16

I left the driftwood pieces outside so that the rain could wash any residual salt out of them. It rained overnight, and the next morning they were water-glazed, giving up their true colours.

We forgot about this fishing float I’d found— very Jeremy Fisher!— until Kev later re-found it in his pocket. It was the only human-thing we brought back.

It’s near the start of the book, when Melville is laying the doomy omens on thick and fast.

The worker’s onesie

Seafood

In researching this piece, I discovered that the pā at Makara dates to the fourteenth century: Heritage New Zealand: Makara Pā

According to the Internet, this is also Mahy: Rooms for Rent.

English word

Kev: “There is a correct & safe technique called 'pencilling' for felling a tree that's more than 2 bar-length in diameter. That wasn't it!”

Noted…

If I had a fish-tank full of dermestid beetles to eat the flesh off the bone like my friend Bruce does, maybe I’d be more inclined to take things home in plastic bags. But as it is, the only bone I’ll take is one that’s already perfectly clean.

Stephens Island is notorious for the fact that the lighthouse keeper’s cat single-handedly slaughtered the only remnant population of a species: the flightless Lyalls / Stephens Island wren. (According to NZ Birds Online, this may be an exaggeration— there was likely more than one cat involved: https://nzbirdsonline.org.nz/species/lyalls-wren)

On the way back I checked the map and found that the hill track links to the middle of the big bay, so people were probably doing the loop, over the hill then round the beach.

Bird caller

Kev got stung in the hand once by a stingray he’d hooked— he reckons it was the second-most painful thing he’s ever experienced.

These just get better and better!!!!!

Amazing drawings! And loved being able to read this from bed and feel like I have just done a big rewarding walk. Beautiful