“Inanna sang:

—He has sprouted; he has burgeoned;

He is lettuce planted by the water…

My well-stocked garden of the plain,

My barley growing high in its furrow,

My apple tree which bears fruit up to its crown,

He is lettuce planted by the water.”1

When I worked as a hammerhand my boss insisted that the last bit of the workday be spent cleaning up the worksite. (As menial labour, this job often fell to me: pushing broom, as it says in the song.) Leaving things tidy was part of V.P.— Visible Progress. Ideally, according to the theory of V.P., a day’s work should effect a transformation dramatic enough to be instantly seen. It is not enough that you should labour; it is part of the labour to render the labour visible. The relationship between time, labour, and appearance is not, however, proportional. Six hours of hard exacting structural work may make little visible difference, whereas ten minutes cleaning can transform a space. We know this, but the client does not. There is a kind of trickery or performance at play, then, for the benefit of the client’s eye, the client’s ongoing FEELINGS about the work— V.P. keeps the customer satisfied.

The last day of moving house reminded me of this. The vacuum cleaner gave up the ghost halfway through the kitchen— I guess I’d cooked its guts trying to get it to suck harder— so it was back to human-powered broom and brush. Another thing about the labour of cleaning is that the difference between none and some is far greater in terms of effect-for-energy than the difference between some and a lot; the effect of ten hours cleaning is not so much greater than the effect of three hours’ worth. In fact, the reward for labour decreases exponentially, until at a certain point one is gilding the lily with things like polishing mirrors and sponging smudges off ceilings.2

Cleaning is about vibes, too. My friend Bex used to call cleaning ‘house-love’, in an effort to propagandise recalcitrant flatmates: but actually there’s something to that. Home is a feeling, and the aura of a house can be polished or freshened by judicious application of energy. When my house was ‘my house’, I kept it pristine.3 When it was no longer ‘my house’ despite the fact that I still lived there, my intrinsic motivation for cleaning evaporated. It was not for my eye, my feelings, my pride any more: it was for ‘the client’ now— for the outside eye— and that made it work instead of joy.

Kev, recently (a spoonerism): “Break bed first thing in the morning. Break bed?! BAKE BREAD!”

That’s what you do on the very last day, though— you rise and break bed first thing in the morning. Before: personal den, bedchamber, dream-crucible. After: naked clothes-rail, bare boards, anonymous room.

My house was at the top of some thirty-one steps, set in many and varied flights. Wood, concrete, jinks and quirks, wrapping around corners. Those stairs were the moat to my castle, the feature that set my dwelling apart from the world. I measured the elevation in my mind against the blue-painted tsunami line on Robertson Street, feeling that I was now (almost certainly) above all of that— unlike at my old house, where it seemed probable that in a big enough quake, the top house would fall down on us, pinning us under rubble to wait out the one minute before the tsunami. That is to say, I felt safe.4

At the top of all those stairs, the homeward path: a passageway between (on the one hand) the overhanging seaweedy tentacles of harakeke leaves and the bird-of-paradise Strelitzia with its pointy bud-beaks, and (on the other hand) my front neighbour’s garden with its lolling Buddhist-orange calendulas, its overshot Fibonacci’d greens. Everything reaching or charmingly spilling into the way. (Also the triffid-like, side-gate-guarding beast of a harakeke, with its huge flower-paws that slapped me in the face after I’d wrestled them aside to pass, springing back on their strong stems, splashing me with nectar and / or rainwater. Often, lately, these flowers would be hosting a lordly yellow-pollen-faced tūī, who’d wait until I was almost close enough to touch before exiting with a bounce.)

The wooden fish with the pāua eye that was mounted on the gate came loose a few days before I moved. I don’t think it was because I knocked it, it was just one of those object-lessons, like the time the hundred-year-old string of sapphires gave way in my hands when I held it up to assess it for re-stringing. The fish dangled by its tail for a while, then fell off entirely on my moving-out day: its nails had rusted through. Things fall apart. (Salt air.)

On the last day of moving the stairs altered their friendly aspect. I carried furniture and boxes up and down the stairs, toiling like an ant in the sun, again, again, ten times, twenty. The impediments became more and more impedimentary. Gradually, through sheer brute repetition,5 the charming path became an obstacle, a trial, an enemy. Unaccustomed as I am, when I got out of the car an hour or two later I stepped into an all-over ache— my muscles had cooled and set.

We drove from one weather into another. Upcountry, the small town was rain-wet, a deep saturated green. Unpacking the car, I heard a falcon’s call. Looking to the West, I saw them, a courting pair of kārearea silhouetted against the apricot-coloured clouds.

The next morning. Kev at chapel, grafting tomatoes.6

Grafting seems a branch of botanical wizardry, a process with a high necessary component of magic. When trees do it— when they rub each other raw to the point that their flesh melds into one— it’s called inosculation. In Latin, osculari is to kiss; so inosculation is kissing-into. The conjoined trees must be closely related enough to fuse in this way; indeed in forestry the pair of inosculated trees are called gemels— ‘twins’7— a word that branches into geminated, geminating, geminative; words that are twinned with the word-family of germinated, germinating, germination, a sprouting forth, budding or shooting; they also call to mind generated, generating, generative.

(These words are all scions of the growthy word-family descended from the Proto-Indo-European ancestor-word *gen(e), meaning to give birth or beget. A comprehensive family tree here: Etymonline - gene*. Conspicuously absent from this list— where it most definitely belongs— is the ur-word cunt.)

Inosculation can also happen in the human body, in skin grafting: the cut vessels on the underside of the graft and the capillary beds in the wound must reach out to each other— they must anastomose, another word for a connection between openings— a process which takes some 48 hours.8 The graft turns pink as blood (sap) starts to flow.

(This is also how birds fuck: rubbing openings ((cloaca)) together. Where I saw the courting falcons sky-dancing yesterday, this evening I saw the thinnest eggshell-curve of moon hanging in the sky.)

Graft, it must be said, is also a word for hard work. Kev thinks, though, that this slang usage is from the German graben, to dig; the same as the word grave.

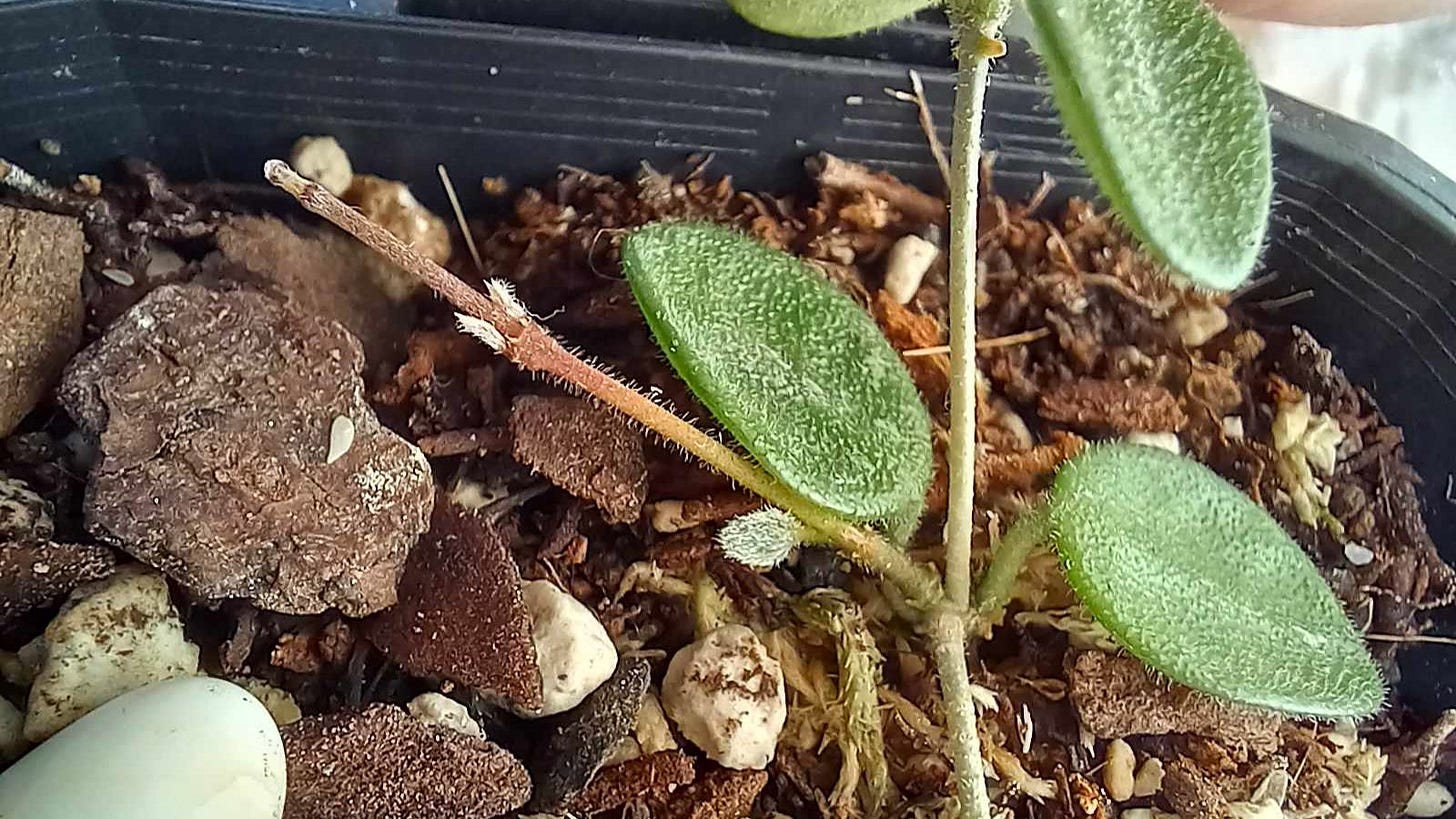

Before the healing, the wound. The place where a graft heals together— where it takes— is called the union. A cutting, however, strikes. I had left my birthday Hoya serpens in the little greenhouse chapel a few weeks back, and when I opened its humid plastic bag, this is what I saw:

Anyway, enough about moving house. That’s all done now. I’ve severed my roots, but it doesn’t hurt— so maybe I’m more like a free-floating dandelion seed. The day after tomorrow, I fly to London, inverting hour and season at one stroke. (This seems a mind-boggling transmogrification, but I know it’s theoretically possible— other people undertake it on the regular.) Reverse colonisation; I hear London is full of tī kōuka and harakeke.

Travel seems to me to be a kind of biological sifting. Plants are forbidden on aeroplanes, tame animals likewise. Wild animals have their own territorial borders, but they cross human borders at will, and they can also cross oceans, swimming, floating, or flying.9 As for our species— some kinds of humans are prevented, stopped, detained; while others are allowed— expedited— to move from place to place.10 An accident of birth designates me the second kind of human, so like Inanna, I’ll pass through the manifold gates to another realm— English Autumn! I am but a simple peasant-Wizard with little experience of such reversals, and I have no idea how it will feel. I’m very curious, though, about what the city of London will choose to show me. Time will tell!

A 4000+-year-old Sumerian love song

It’s probable there are people reading this going ‘You don’t sponge smudges off your ceiling?! You animal!"‘

It was the first time a house had been ‘mine’, so this was interesting to note. Always, before, the application of cleaning effort was intertwined with communal motivations to do with being a good citizen, caring for others, keeping my end up, fighting the omnipresent tide of chaos, etc.

To anyone living in a flat or other communal-living scenario, I offer the group cleaning hack I invented: the Reverse Roster. So, you know how you can have a prescriptive jobs-chart, say with two superimposed wheels, one with people’s names and one with tasks, and the wheel rotates so the two sets match up in sequential order i.e. Bathroom / Rosie; Rubbish / Betty; etc. etc.? My (more anarchist) system works on the principle that people have different preferences and strengths, and that it is the input-of-energy that makes things fair rather than the exact sharing of every task. For instance, I like anything to do with water (dishes, bathroom) but I hate the vacuuming (not sure why, the noise, or possibly the frustration of having to use a substandard tool— flat vacs usually suck by not sucking very much).

Reverse Roster: Draw a grid. Down the left hand side, label each row with a task: Dishes, Toilet, Rubbish, Vacuuming etc. (There’s no limit to this except space. You can add things like cooking dinner, really any domestic labour that a single person undertakes for the household.) Along the top, label each column with a set of dates, generally a week, i.e. 3rd - 9th November. You might have three months worth, if you’re using a sheet of A3.

Stick the Reverse Roster to the fridge with magnets and attach a pen on a string. Usage is simple. When you complete a task, write your name in the appropriate cell. (This gives a hit of dopamine much like putting a star on a star chart: it’s a proof, a win, achievement.) What the Reverse Roster does is it makes invisible labour visible. After a while, you will begin to see patterns: this person always does that job. So and so has done the dishes twice as much as anyone else. You can also see who does little or nothing— very useful to know.

Note that the Reverse Roster works by gentle social pressure: its efficacy relies on people being embarrassed by their slackness. Therefore it will not work on children or the entirely shameless. The entirely shameless you can kick out of your flat, but children you have to continue to put up with, I gather.

Due to the aforementioned steps, buildings in front, vegetation, and possibly other more numinous factors, the house lay under a cloak of invisibility. I could give people detailed directions, but they would get lost on the way, unable to find the house. Eventually I realised it was easiest just to go down and fetch them from the street.

'Reps’

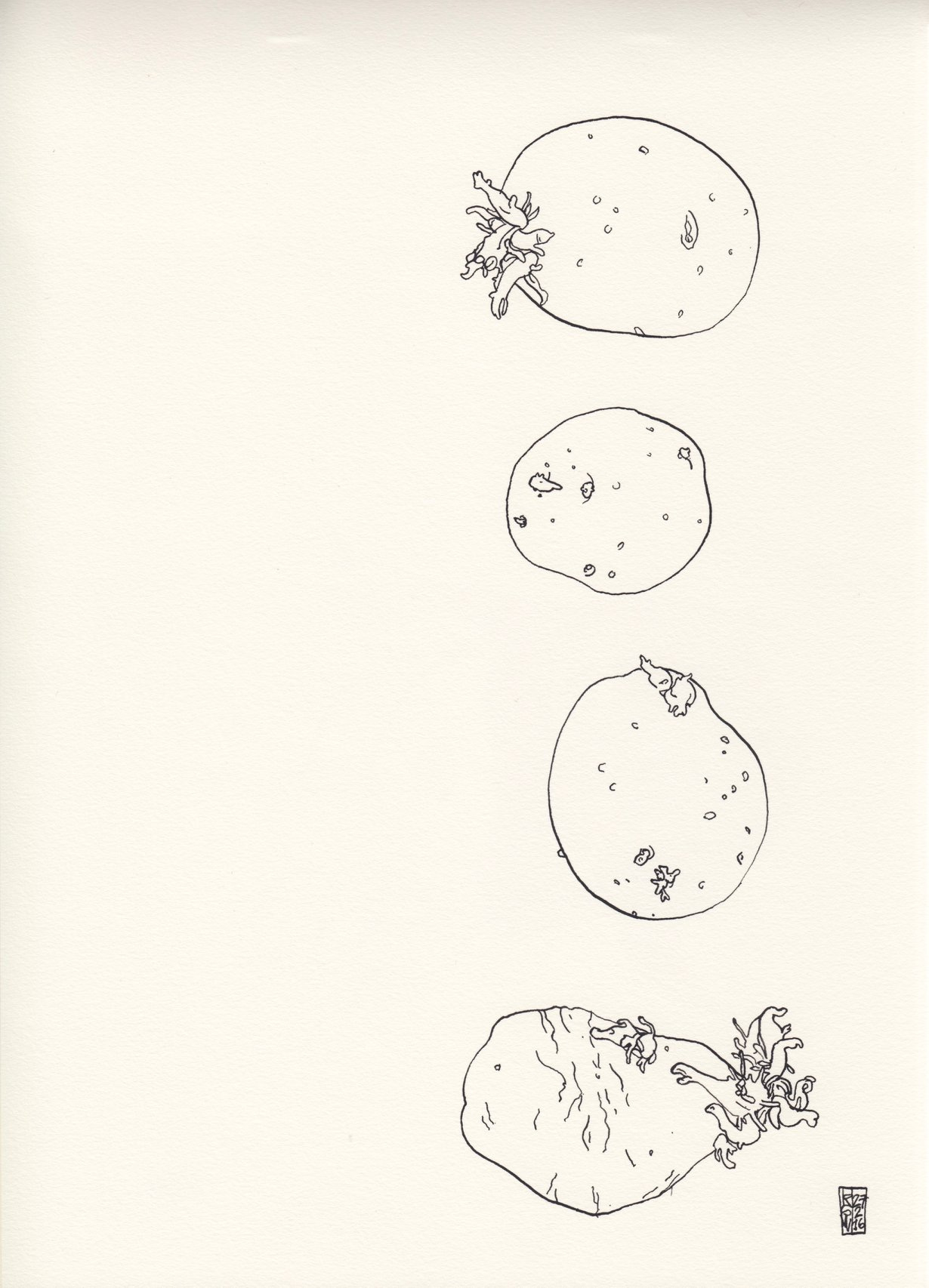

Against the wall, these chitted seed potatoes waiting to be planted— earth-eggs:

I made a daily drawing about sprouting potatoes. The title— a Walt Whitman quote— is The smallest sprout shows there is really no death.

'Gemini.’

Gem originally meant both a bud and a jewel, and sometimes an eye.

See also a gemel- or gimmel-ring: two interlinked rings worn kissing on the finger. There is a whole category of folk songs whose plots hinge upon a piece of jewellery separated into two parts— one half is taken by each lover, then years or decades later the matching half is produced as proof of identity. These are sometimes named broken token songs. It beggars belief that a lover would change beyond recognition in a decade, but the sea, or the war, or just the world can ravage a person, I suppose.

Kev: “Then there are things like nerves, that don’t even have to touch but can reach out across the gap, as if they can smell each other. They don’t always join like to like, but the brain sorts all that out eventually.”

I was recently reading about how the ancestor(s) of Harpagornis / Hieraatus moorei, the giant eagle that was Aotearoa’s apex predator, were likely a pair or a single gravid female blown across the sea from Australia: DNA analysis has shown that Harpagornis was most closely related to Hieraaetus morphnoides, the Australian Little Eagle.

Anything that lives on us or in us— parasites, bacteria— counts as us.

Kev says that the reward-for-labour-decreasing-exponentially thing is sometimes called the 80/20 rule: 80% of the results come from 20% of the effort.

Cloaca are sometimes called primitive openings because they perform all functions I think.

There are many potatoes in my garden left from the former owners' gardening. I wanted to encourage them but stirring up the soil caused the (temporary guest) chickens to take interest achieving the opposite result. The drawing softens the potatoes making them more beautiful than the photos in egg cartons.