Simone Weil: “[W]e possess no other life, no other living sap, than the treasures stored up from the past and digested, assimilated and created afresh by us.”

Woody Guthrie: “The world is filled with people who… try to make slaves of all of us— and they have their music and we have ours.”

Note: this is a long post, with many links and footnotes, so I advise clicking through and reading it on Substack rather than in email form. If you hover on the footnotes they will pop up in little boxes. Song-links will take you to the song mentioned.

I arrive at the festival and see a kārearea, a falcon, flying over the tops of the pine trees, calling its alarm call kek-kek-kek-kek-kek! I pull out the karanga manu and call back to it. It doesn’t alter its call or its flight but keeps calling as it describes arcs, a spiralling dance over the dark sawtooth, appearing and reappearing and finally disappearing behind the trees. Kev speculates that what it was saying— and thus likely what I was also saying in falconese— was fuckyou-fuckyou-fuckyou!

What even is Trad? This question is the bone the dogs love to chew on in groups like The Ballad Tree, where folklord-philosophers argue endlessly, saying What about this song though? Or that song? What if it has old lyrics but a new tune? What if it’s written in the style of trad? (Strictly speaking, no single person can write in the style of trad, which is by definition a collective work.)

Traditional music, when it comes to songs at least, is mostly defined as ‘author-unknown’. A song might be a Child ballad, or have a Roud number. In practice the definition is far less clear. There are many songs in the group repertoire of my singing buddies that are rightly considered bangers even though they’re contemporary. Then there are parallel traditions— trad doesn’t just belong to the British Isles. New Zealand has its own traditional songs, for instance. (The ones in te reo Pākeha1 mostly concern gold-panning, sealing, and whaling.)

After the festival, John, a rock’n’roll devotee— a Trad-hater married to a Trad-lover— indulges in a spot of Devil’s advocacy on the subject of What even is Trad?

He’s talking to three hardcore Traddies, so he is heavily outnumbered.

Look, I say, I’ve thought about this a lot, and I’ve come to the conclusion that even if it’s very difficult to draw the dividing lines at the edge of a thing, that doesn’t mean that thing doesn’t exist. Trad is real, yo. It’s a feeling. You know it when you feel it.

At most folk festivals, Trad singing is one sub-genre among many. Some people obsess on diddly (instrumental Irish tunes); or bluegrass, Americana and the like; or feel a strong need to perform their own singer-songwriter stuff. (Some are born to sweet delight, some are born to endless night...) There is even a small cadre of hardcore Mediaevalists who jam out on the hurdy-gurdy and nyckelharpa for hours. Trad singing, though, feels to me like the bones of folk. No gear required; just your voice.

Tradfest is like a singing session— a Wellyfest session, say, the kind that starts around 10 p.m. and goes on until 3 a.m.2— expanded into four days and nights. There are instruments at Tradfest, too, but far fewer of them than at other festivals: singing is the main purpose. It’s like, what if you took seventy-five or so of your singing buddies, the best folksingers in the country (or at least the North Island), and confined them to a small camp in the middle of a very large forest. And make it in a cold season, so they are all encouraged to congregate in order to keep warm.

When I rant about folk gripes at Tradfest, people get it, unlike in the outside world. Like the singing-off-phones thing: it’s a no-no at Tradfest.3 Some people still do it, but they will get stick for it. Jack, spooning in porridge and stewed apple, says he’s holding the line— he’s never used notes on stage. (That is, he sings only from memory as a point of principle. Old school!) I say that in a setting like this, unless the song is obscure beyond obscurity, someone else will know it and help you out if you forget. Then suddenly I say Oh!— the other man sitting at the table with us is John, the one who prompted Jack the night before.

The opening night concert is called ‘I learnt a new trad song’, and it’s a great leveller: even the best of us have to sing something we’ve never sung before. (I went down a music-hall rabbit-hole and sang one of Tony’s Cockney songs, They’re Moving Father’s Grave to Build a Sewer.) For his song, Jack told us a story about how he had been one of the last to do National Service in Scotland— it was ended while he was doing it. He apologised to anyone from Orkney, which he said was actually quite nice, then sang Bloody Orkney. I’d never heard it before, and when Jack dried up about halfway through there was a long pause. Maybe nobody else had ever heard it either. Then someone—John— piped up: “It’s something about the theatre. Cold seats.”

That was enough, Jack was away again.

”The bloody flicks are bloody old,

The bloody seats are bloody cold,

You can't get in for bloody gold

In bloody Orkney.”

John is the New Zealander-turned-Australian who asked Chris which festival he should come to, as he was pining for harmony over in Brisbane.4 She said, Well, you could go to Wellyfest, but Tradfest’s the one for singing. He knows half the people from thirty years ago, but I’ve never met him before: I was too young then.

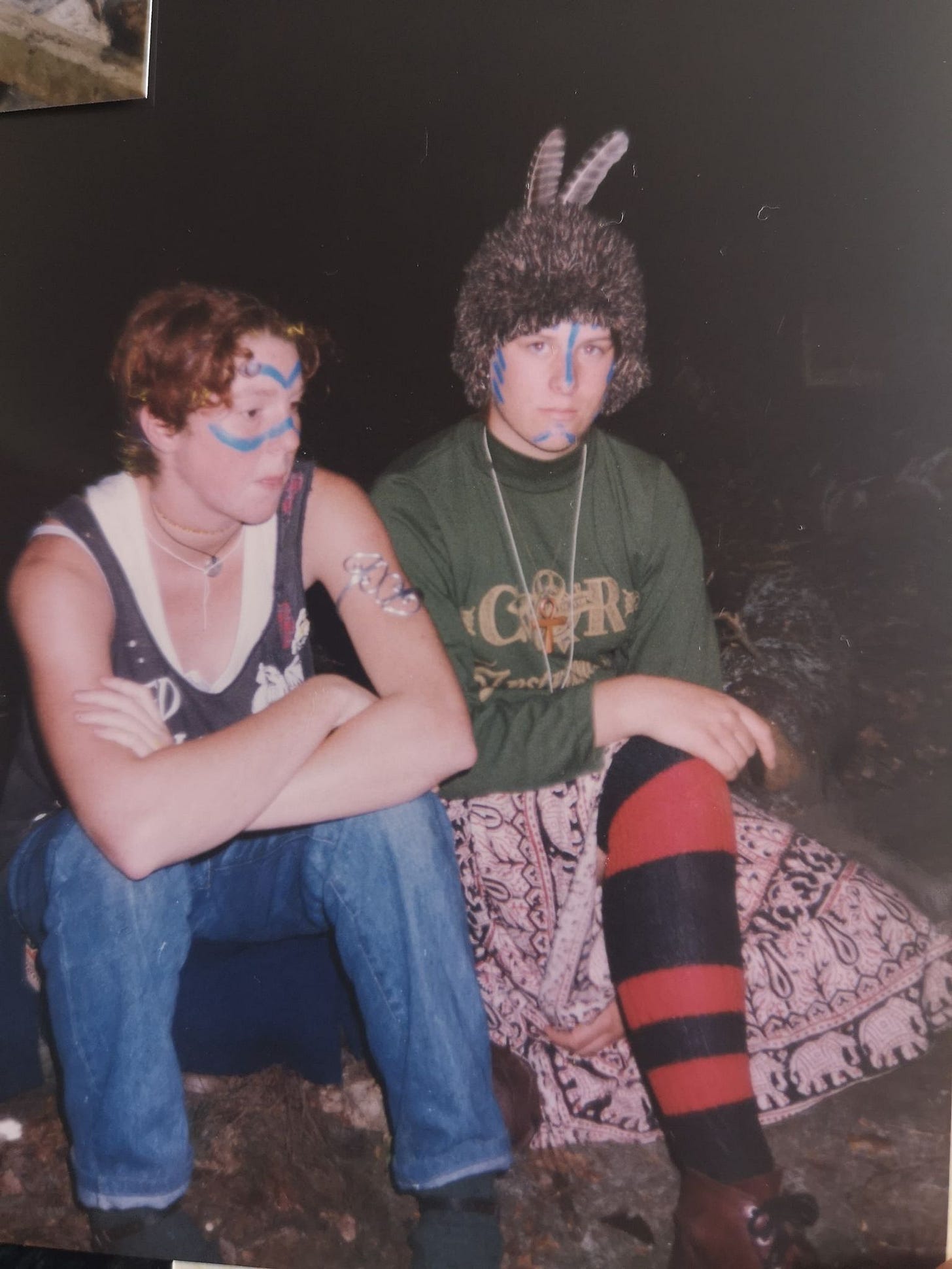

Now that I think on it, though, thirty years ago I was 14, which is pretty much exactly when I first started coming to folk festivals by myself— but it took me years and years to start getting to know anyone. It was becoming a singer that brought me into this fold, and I don’t have a clear memory of how that happened. I remember how certain songs suddenly emerged from the sonic wallpaper and took a hold of me: Let me tell you that I love you, that I think about you all the time. Caledonia, you’re calling me…5 The song Andrew played all the time on his guitar, until we couldn’t help but learn it, Tell me Ma when I go home, the girls won’t leave the boys alone… And late at night in the homebrew tent yelling Chicken on a rock! (It’s Chicken on a raft, but nobody corrected us.) Marmite-tasting homebrew in green plastic bottles flowed like any fountain, free to those who brought their own cup. The other youths wanted the beer. (Beer the bait, shanties the hook…)6 I was an uptight, straight-edge teenager,7 rebelling against rebellion out of cussedness, but I went along too, because I wanted to hang out with the cool kids. Their pastime for most of the festival— this was at Auckland Folk Festival— was playing Nirvana on the guitar, getting drunk, and pashing each other. I hadn’t yet realised that I would never be cool— that my true comrades were the ones singing.

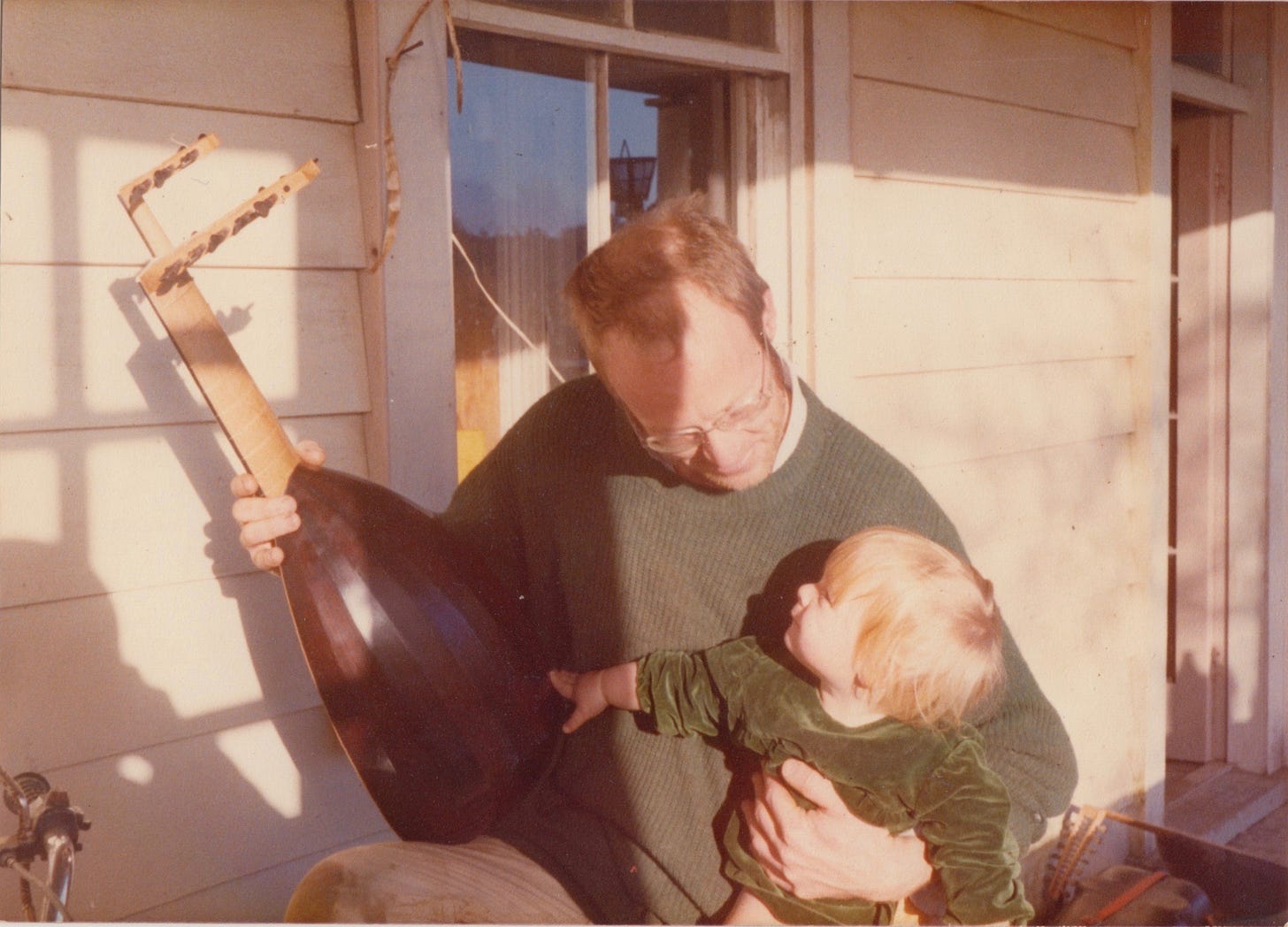

Folksingers say So, how did you get into singing? They are a type of people who are— by definition— interested in history, in the past, so they ask origin stories of each other. When I was very small, my Dad was a folksinger. He played the guitar and sang songs like On a wagon, bound for market, Donna donna donna donna, and There once was a troop of Irish dragoons, came marching down through Fivie-oh, and At the top, twined in a true lover’s knot, the red rose and the briar. Bearded men, ten chess boards in a row, the green stuff.

Like anything else he did, my Dad did folk music obsessively. Dick Gaughan and Nic Jones and The Johnstons on high rotate. I loved Canadee-I-O, the triumph of the stowaway girl, She’s dressed in silks and satins now, and she cuts a gallant show. I loved the Scots that I could understand not a word of, O horo, the Gillie Mor, whit's the ploy ye're on sae early?8 I loved the strange sounds of the Irish Gaelic that we sang along with, likewise.9

My Mum sang songs at bedtime, You’ll take the high road and I’ll take the low road.10 I could never decide on a song, playing for time to delay lights-out, but my sister always asked for the same one: She’ll be coming round the mountain when she comes.

I have old, vague memories of the memories-of-memories kind— motifs— falling asleep on a hard chair at Titirangi Folk Club, swinging out over the creek on the rope swing at Knock Na Gree.11 But my Dad soon put away the guitar and played only the lute. Early music took over. Dowland, harpsichord, high-singing ladies. (High-singing men, and all…)

I guess that was the amniotic fluid of my singing-self, a constant wash of songs through my baby ears. But none of that is the story of how I came to sing folk songs. I can remember standing in that same Auckland Festival homebrew tent (for some reason there were a number of years when the late night homebrew-and-drinking-songs session was held in a large white tent in the middle of the field, possibly because it was too noisy), the air close and warm, a box of bodies, a wall of sound. It was a first-come-first-served session in both senses of the phrase— booze and airtime— and the culture was one of big men with big voices.12 Every time a song would end I would gather my nerve to push my way through, but I could never summon enough nerve to do it before someone braver, bolder, older, louder, would jump in. Whole nights could pass in this way, a bundle of nerves, but never enough nerve to claim the centre— to lead.

I can’t remember what song I had learnt to sing, but I must have had something prepared or I wouldn’t have dared to think about it in the first place. I find it strange that I can’t remember, but learning to sing is a gradual process. It feels accretive, like stalactites forming from limestone-water. But it is also willed, a house built by collecting sticks one likes the look of. Every festival, every session, there’s a good chance that a song will reach out and take hold of you by the collar and say sing me! It happens by way of a line or two or a chorus lodging in your mind like a grass-seed: just that one little bit, then you start to feel like, well, what comes next?

(This was the one for me this time, sung roisteringly by Paul and Noel and Jack, in the kitchen. Leaning against the metal bench, a teacup of Ardbeg in my hand. By the end of the song I’d almost learnt the chorus:

You can see them a’, the lads o’ the fair

Lads frae the Forth an’ the Carron water

Workin lads an lads wi’ gear

Lads wha'd sell ye the provost's dochter

Sodjers back frae the German wars

Peddlers up frae the border

An lassies wi’ an eye for mair than the kye13

At the trysting fair at Falkirk.)14

A folk singer’s songs are both common and personal. I draw my repertoire, an ever-changing thing, from other people, and they draw from me. I have my repertoire, and we have our repertoire, our collective knowledge-pool. Go hunting in the thickets of the Internet, find an obscure song, prepare it, sing it well, throw it in the pot. It doesn’t belong to you: other people can learn it too. However, some songs do sort of belong to someone, for a time. Someone can do a song so well that others leave it to them. A song and a singer can have a love affair, a relationship, a marriage. The beauty of it is, though— nobody else is you. Your version is your version, an absolutely unique thing in the world. To learn a song is to take it into your body, a collaboration, a symbiosis; mycelium / roots.

Gerard has a song about how the singers who have gone will be singing once again, when we sing the songs they sang. There are a number of songs like that, we may or might never all meet here again. Goodnight, and joy be with you all. Folk is a medium concerned with time. We are the living veins through which the life-blood of history runs. The song is a thing passed down; we hold it briefly before handing it on.

Tony was there— his ashes in a Lagavulin bottle— and we had a whole concert where we all sang his songs. Sean and I sang Bold Wolfe together. Charlie said she could see Tony sitting there, in his blue denim shirt. (When Kev got home, he found that the rosemary cuttings we’d worn in our lapels at Tony’s funeral had grown roots; he potted them on.)

In the session themed Green, Jack sang the song that spawned the term mondegreen, meaning a misheard lyric: They hae slain the Earl o’ Moray, and laid him on the green. (People heard ‘They hae slain the Earl o’ Moray, and Lady Mondegreen.’ That’s the folk process. Though we also say that, jokingly, about a whole lot of other idiosyncracies. The folk process is a basket into which we throw any old nonsense.) I’d never heard The Earl o’ Moray sung before.

I sang Oak and Ash and Thorn, a very green song. Tricia sang Green Grow the Rushes O, and Paul whispered his Union version in my ear, Two, two, the worker's hands working for a living O, one is workers' unity and evermore shall be so. He said you could tell what someone’s political affiliations were by what version they sang: for instance, Communists sing Red Fly the Banners O.15

The water-drops freeze on the tent overnight, and the rainwater in the plate left outside is a crazed disc of ice a centimetre thick. Ken walks to the hot creek at dawn but by the time he gets back, an hour through the frosted pine-slash, he’s cold again. When the sun touches the frost, it becomes wreaths of steam among the dark pines. The wet underwear that I wore in the creek is frozen into the draped form it took hanging over the wing-mirror, and crunches when I unbend it.

The creek is more warm than hot, like a bath that makes you want to crank the hot tap. The sun is shining through the conifers. A clean pine-needled bank to lay my clothes on, stairs made of roots. Steam rising from the water. There are naiads in the creek: unearthly beautiful dark-haired maidens sitting under the small waterfall, near their calm Mother who wears a filigreed cloak of tattoo. Deb and Jenni and Alison and I sing gospel, and the ferns on the stream-bank snag in my hair. Jenni points out small birds flitting in the branches. I dig my fingers into the fine gravel underwater; inside the stream-bed it is warmer, as if the warmth seeps up from below. In the shower afterwards my underwear is full of debris. (I washed it when I got home, but still, now, the sports bra I’m wearing— the one I wore into the creek— smells like riverine sulphur, a whiff of sweet Hell.)

Chris: “I wonder, if everyone here sang all the songs they know, how long we’d be here for.”

Me: “Weeks. Months. Certain people would skew the statistics— they’d be weeks singing.”

Jack is her Dad, and Ian is doing a project of recording Jack’s songs. Jack produces a master-list of 500 songs.

Ian: “Which ones do you want to record?”

Jack: “All of them!”

Kev used to sing his whole working repertoire through in the time it took to do a tractor round of the orchard: four and a half hours, 63 songs, singing to the drone of the tractor’s engine. “Not including the turns between rows, which require concentration and are thus unsingable.”

It was Vicki’s first Tradfest. She had a small leatherbound book with gold flowers embossed on the cover, in which she wrote down every song sung over the weekend. (There are only two adjoining rooms to sing in, and as I said, it was cold outside, so not many songs can have been missed.) Towards the end of the festival I asked her how many pages she’d filled. “Twenty-one.”

Her writing was tiny. “But then you ran out of paper?”

”Then I ran out of paper.”

When Vicki asked me to sing in the collaboration concert— we sang a Manx lullaby—16 she wrote the lyrics on the last sheet of her small book, tore it out, and gave it to me. That’s how I knew she had run out of pages. Did I not sleep on the cold wave’s crest, where many a man has taken his rest. Chris, who was M.C.ing the collaboration concert, said she was going to introduce me and Vicki as The Scribes, since we were both always writing in our books.

Barnaby, too, was always writing. I asked Barnaby if he went to Steiner School (because of the intactness of his innate eccentricity). He was mildly insulted and told me that au contraire, he went to a Catholic Boys’ School. Like me, Barnaby uses green ink in a sloping cursive, with sideways blocks of red at the edges.17 “What does the red mean?” I asked him.

“The red is things that need to be in red.”

Writing about singing is difficult, because it‘s so experiential. You had to be there, as they say. Group harmony-singing rearranges my atoms. After some hours, it becomes psychedelic. If I close my eyes, I can’t tell where the edges of my body are any more. It fills me with liquid elation, and everyone else is running on that same liquid elation. It’s the closest I come to religion, and it’s pure fun. Geezercore! Peasantcore! Ludditecore!

Noel sings Boadicea, Boadicea, Boadicea of the Iceni, to the tune of Taumarunui on the Main Trunk Line. After the festival he scans the relevant page of the Alf’s Imperial Army Fifth Waikato Dragoons Songbook for me:

She’s just an ordinary sheila

But she’s hardly ever home,

Cause she’s out there in her hobnailed boots

Fighting against Rome…

“Folking and joking!” says Noel.

On the third night something amazing happened. Kev and I had been asked to sing in the Invitation Concert. We were up last, and Tricia, who was running the concert, asked us for a couple of rousing, crowd-pleasing joiner-inners to finish. Kev and I went to the edge of the pine forest to rehearse. It was drizzling, and I leant on the trunk of a pine tree that left sweet-smelling resin on my coat. (Sometimes these makeshift run-throughs, outside, with no audience, are the most beautiful. Like when Kev and I rehearsed with Chris on the verandah, Adieu Sweet Lovely Nancy. We sang it through once, with Chris improvising a third harmony, and at the end we all stared at each other, awestruck, and I said, “Chris, do you want to join our band?”)

Anyway, Paul finished his set of four songs about Dundee, his hometown— a jute town, where his Mother was a bobbin-winder— and it was us up. I said what was in my heart, which was that though I’d heard some amazing singing in my time, I had never heard singing as amazing as I’d heard this weekend. “I love you guys.”

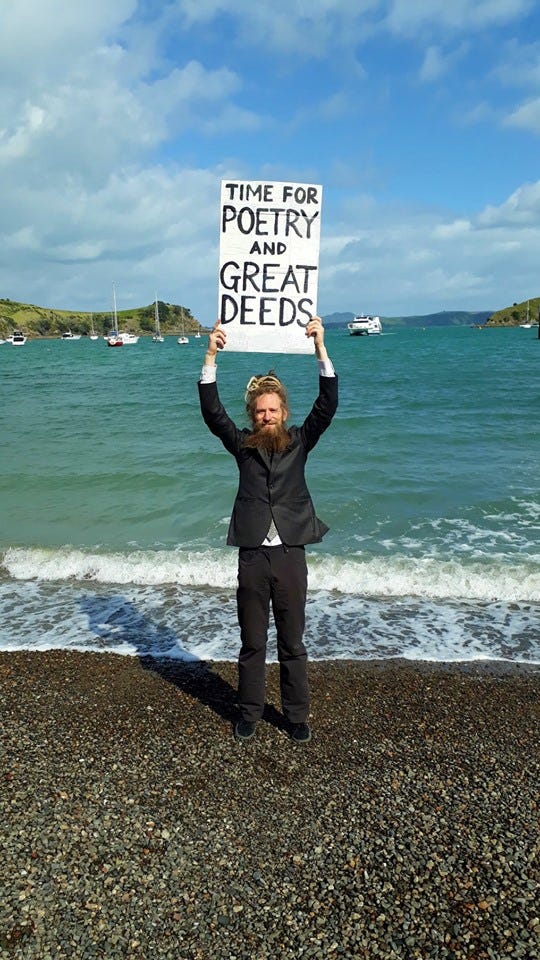

For our last song, I wanted to sing something we don’t usually sing: “Who’ll be the lady, who will be the lord, when we are ruled by the love of one another?”18

I started it at a cracking pace, but the audience pulled the pace down. Usually when that happens, it’s annoying, but this time I was like OK, sure, we can do it like that. Everyone wanted to stretch it out, to wring the harmonies from it. I was on stage, but it was safe, I was with my friends, we were making this together, I was in the river of music and I followed where the current took me. The song grabbed hold of me and I forgot myself, all my self-consciousness was gone, and I stepped forward into the glorious sound coming back at me, labour and spin in fellowship I say, labour and spin for the love of one another. I know this song well, it’s so simple, and it’s a statement of my political faith, it’s truly mine that way: every word I sing I believe. We were all part of this big magic, seventy voices in anarchic harmony. I’ve never felt that before, that performance-rapture, and I thought Oh. This must be that thing that people talk about, those people who love the limelight. Afterwards people came up starry-eyed and said Thank you, thank you, and that was amazing, and what was that song! someone said— it was the Australian, John— then we all went and had an amazing kitchen session that turned from political to filthy19 to cry-laughing hilarious.

Thinking on it later— that full stellium-in-Leo moment on stage— I thought, I’m like a diamond. I can only sparkle in the right setting: in a group of what Tricia would call my very best friends. Otherwise I’m just a small loose rock. Crucially, folksinging is the only one of the crafts I practice that is not solitary. It’s an art that is embedded, absolutely contextual. The high points appear suddenly from the everyday business of hanging out, yarning, eating, singing: magic rises out of the mundane like thermal heat rising through the stream gravel.

A folk festival parallels the form of a village. (A village en fête— everyone is on holiday.) Maybe it’s the size; Dunbar’s number, the number of people one can have a meaningful relationship with, is 150. Maybe it’s the fact that the whole day is spent together, from breakfast to wee-hours whisky. Or maybe it’s the way that everything is built on years— decades— of friendship. (It’s also like a village in that you don’t necessarily love everyone, or everything they do. There is a certain amount of wading through the mud, tolerating stuff one doesn’t enjoy.)

For any given festival, it can take days to get there, to get to that magic place; days and nights of pleasurable collective labour, the work / play of memory, response, and expression (or I might not even get there, if the stars don’t align right). It’s the heft of the accumulated years and decades, though, that make people family to each other.20

I can only sing if it feels correct. That sounds diva-ish, but I think it’s more that singing is high energetic Wizardry. In Sean-nós,21 the singer might sing with their eyes closed, or face the wall. People might encourage them, or hold their hand. It is understood that singing is a naked thing to do, and the other people help to make the singer feel safe. There is a subtle but very important distinction between performing (as it is generally understood) and folk-singing. Performance is hierarchical, with a clear division between performer and audience. Folk music is egalitarian, with no distinction: I sing, you sing, we sing. It’s humble, not fancy. People are mostly dressed casually, the setting is not grand, nobody is showing off. And the form is simple— great mastery can look effortless.22

The old people make much of the young people as being the future, but I see that we are the same people walking the same road. We were them once, and if they keep walking, they will be us.

William Butler Yeats said of hearing folksingers in Kiltartan: “The voices melted into the twilight and were mixed into the trees, and when I thought of the words they too melted away, and were mixed with the generations of men. Now it was a phrase, now it was an attitude of mind, an emotional form, that had carried my memory to older verses, or even to forgotten mythologies. I was carried so far that it was as though I came to one of the four rivers, and followed it under the wall of Paradise to the roots of the trees of knowledge and of life. There is no song or story handed down among the cottages that has not words and thoughts to carry one as far, for though one can know but a little of their ascent, one knows that they ascend like medieval genealogies through unbroken dignities to the beginning of the world. Folk art is, indeed, the oldest of the aristocracies of thought, and because it refuses what is passing and trivial, the merely clever and pretty, as certainly as the vulgar and insincere, and because it has gathered into itself the simplest and most unforgettable thoughts of the generations, it is the soil where all great art is rooted.”

I leave the festival, and after a while I notice that I am biting my fingernails. Back to the real world. It’s quite bad out here. Folk music is another flavour of real, really real, good medicine— not escapist in the sense that saccharine pop is— it’s not trying to sell you anything. Ursula Le Guin says that in the hard times coming, we will need (to be) realists of a larger reality. One of the main themes in folk songs is Times were hard, and this is what it was like. This is what we felt and did. The people of the past were not so different from us: they speak to us still.

Tyson Yunkaporta says that people shouldn’t come looking for indigenous wisdom from people like him— they should seek their own indigeneity, the old ways of their own people. I am descended from settlers. I have never set foot in Europe. But this thread of song and language links me back to my ancestors. I seek to honour them by study and labour and bravery and— as Tyson would say— by Right Story. Where else can I draw sustenance but from my own bloodlines?

When I say that folk songs are transmissions from the ancestors I mean that literally. They are cultural artefacts of astonishing richness. Power, pathos, wit, strangeness, history, humour; altered according to people’s tastes hundreds of times over— the folk process. If a song’s good, it can weather the centuries, changing as it goes, staying alive. Everything is intertwined in the music: politics, art, and history, work, love, the natural and the supernatural, comedy and tragedy. Is this— out here, the so-called real world— more real, or is that?

In te Ao Māori someone who is an eloquent speaker or a beautiful singer is said to have the throat of a tūī— me he korokoro tūī. Singing is a magic we share with the birds. When I think of the tūī, I hear its cracks and burrs and dings: roughness and comedy woven through the beauty, and I think, that is like folk music. And writing this, I hear a tūī singing outside my window, as if summoned. I will crow like a cock, I will carol like a lark, in the light that is coming in the morning!

English

Though I have seen the sun rise on singing sessions

What I mean by this is people looking up a song on the Internet and singing it off their phone, rather than learning it and singing from memory. I have a mental shorthand for this: it’s like when someone sucks the smoke from a cigarette and lets it trickle out of their nose at the same time— a tiny little circuit through the front of the face, eyes to mouth. Singing from memory, on the other hand, is like drawing water up from the well. (To me it feels like pulling a string.) If you’ve worked on a song a lot and you still can’t remember, a piece of paper with the words on is OK, but if you don’t know the song at all, don’t try to sing it in public or you’ll embarrass yourself.

His mind is blown by the singing. My mind is blown by the singing, and I’ve heard some singing in my time.

I was torn about whether to confess that although I loved this song at the age of fifteen or sixteen, I now don’t like it so much. Then I went to have a cup of tea with Brian and he told me a story about Dougie McLean’s pub, the Taybank in Dunkeld. Brian went there for the first time to have a drink with a couple of cronies. McLean came in and announced that the bar would be closed while he performed— until intermission— because he found people getting up and down distracting. A man stood up, outraged: “Do you mean to tell me I’m not to have a pint while you play? You’ve become a real prima donna, McLean!”

Two goons appeared and dragged the man out while everyone booed. Then another guy got up and left, saying he was never coming back. Then Brian and his friends skulled their drinks and left too.

(EDIT: I checked this story with Brian, and I was wrong about the location: it wasn’t in McLean’s pub— these events occurred in Brian’s local, the Lemon Tree in Aberdeen, making McClean’s behaviour even more egregious. Furthermore, the guy who was thrown out was a fellow regular.)

“Well,” I said, “I could kind of tell he was a wanker by his Rolling Stones-esque rockstar hairstyle in that video.”

Brian then told me about a beer ad that was banned in England. The ad, for Tennents lager, was considered tantamount to SNP propaganda. (The video is age-restricted because it concerns booze; sarcastic summary here.) The relevance of this story is that the ad was soundtracked by this very song, Caledonia, though in a kind of heavy-metal-lite version by Frankie Miller.

Me, listening: “Is he American?”

Brian: “No, he’s from Glasgow.”

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again… Shanties are the marijuana of folk music— the gateway drug. Shantytok is responsible for the arrival on the scene of many a youth.

Before that was even a thing

Now that I’ve studied these songs, word by word, pronunciation and meaning, it’s strange to remember the time when I guessed at what they meant. Was it about a battle? No, it was about Communism! Who knew! (I think maybe I thought it was about a battle because of the word mor, which means big— it’s half of claidheamh-mòr, a claymore, or two-handed broadsword— but in this case the Gillie Mor is the Big Lad, the blacksmith’s apprentice.)

This one is about a rich old lady courting a handsome young man: The Hag with the Money.

I’m not sure whether I understood as a kid that this was a language; maybe I thought it was just mouth-music. Last night I heard Noelle McCarthy interviewing Sinéad Gleeson, and they both spoke in Gaelic at the start of the interview. It was cool to hear.

Of all the songs I looked for, this was the hardest to find a good plain version of. It’s too well-known— it’s gone from folk to sentimental sap. Rule of thumb: If the singer is excessively dressed up, whether in a flowing gown or a semi-ironic cream-coloured gansey, and / or if they are gazing wistfully / manfully off into the middle distance, it is likely going to be a Not Good version.

I can tell if a version’s good or bad with the first sung word— sometimes earlier, if I hate the accompaniment.

Cnoc na Grai, Hill of the Hare

Not naming any names, but there were some right old foghorns in the mix

Cows

This is the original, but when I hear it I also hear, overlaid, the version I heard in the kitchen.

I don’t reckon the time I saw Grant Robertson, Labour Minister of Finance, at a book launch, singing The people’s flag is deepest red, it shrouded oft our martyred dead, counts.

Like this, but mostly in English

My ink is frog-green, but Barnaby’s is a classic forest green. Strangely, the other ink I sometimes use is also reddish: I’m pretty sure it’s this one, which used to be called Ottoman Rose; the picture of naked ladies on the label is the same. The guy who makes this ink is a gung-ho American, so possibly he changed the name for ideological reasons.

No online version exists that is exactly like what we sing, but this is the closest I’ve found.

Shoutout to Iris— “I put my hand upon his shaft, mark well what I do say…”

Conversely, this can make it weird, boring, or impenetrable to newcomers, if they are expecting any level of coolness. Noel has a song about this, which goes:

”I tried to sing an old sea shanty,

Down the pub on World Cup Night.

They told me to stick my concertina

Where the sun don’t shine so bright.”

(To the somewhat bastardised tune of Guide Me O Thou Great Redeemer / Cwm Rhondda, which we also use to sing ‘Clementine’.)

'Old style’, traditional Irish singing

I think of it as something like flamenco: the strict, boundaried form is a riverbank within which the channel of passionate expression can flow.

I can't tell you how much I enjoyed reading this and how much I appreciate how the work you did providing links to the songs you reference (which I'm working my way through).

I'm assume there are festivals like this in the States, and if I ever hear of one nearby, I'll be sure to go. I love to sing, and I would love to be in a group of people singing old songs together (I do this at church, but most of the songs in the Episcopal hymnal aren't that fun to sing).

I was born in 1964, at the height (or close to it) of the folk music craze here in the U.S. When I started school, we sang folk songs when we had music class--this was probably the case through my 6th grade year in 1976. When I think back on those days, what interests me is the variety of the songs we sang--old English ballads that came to us via Southern Appalachia; work songs and train songs; there was even a song we sang that I think must have been a Jewish folk song (though I just tried to track it down and can't).

My dad never sang folk songs (I don't think I've ever heard my dad sing anything), but he had a lot of folk records that he liked to play. This was before he went to Vietnam. After Vietnam, he mostly played Creedence Clearwater Revival.

"Ursula Le Guin says that in the hard times coming, we will need (to be) realists of a larger reality." If you have a second, can you tell me where that's from?

,

Hi Rosie, couple things - I do hope that describing singing without notes as 'old school' doesn't consign that necessary activity to the box of old git-dom. Singing off your phone is admittedly where the medium is compounding the aesthetic felony (is reading off paper really slightly more acceptable? Possibly ..) but nonetheless practitioners should be taken out & sunk. Other thing you might like to know is that Tennants thought Caledonia was a trad song & got a narsty shock when Dougie sent them the bill - that might be why the ad was pulled. Cheers, Deb