I Died in an Ancient City

City-Watching Field Notes London / Wellington November 2024 - January 2025

“The street keeps moving, and you’ve got to love the movement. You’ve got to find the composition of the rhythm, lift the story from the motion, understand and not regret that the power of narrative drive is fragile, though infinite. Civilization is breaking up? The city is deranged? The century surreal? Move faster. Find the story line more quickly.”

(Vivian Gornick, The Odd Woman and the City)

My second day in London: the sun’s shining, it’s very cold, and I’m walking briskly through Tottenham, amazed. I intend to swallow some miles. It’s the first time I’ve properly tried out my new boots: so far, so good. Lacking a map or a phone, my plan is to stay on the one road— the A101— then turn and come back along the same road. My feet have settled to the automatic stride, and I’m gazing up and around, at buildings, trees, the sky, a bird. A man I felt following draws up beside me, and I can’t help but smile and make eye contact— it’s the way of my people.

He says he's been walking along behind me looking at my beautiful hair. (I’d washed it that morning, so it was out to dry, and I’d been enjoying the novel swing and slither of it— I had it cut before leaving New Zealand.)2

He asks me what I was looking at, and I say I was watching a shag flying overhead.

It’s because of the wetlands, he says.

Me: “Did you grow up round here?”

”Yeah darlin, just down that road. Alongside all these fake Jewish Zionists.”

When I ask him what’s fake about them? He gives me a wry look like come on now, and says “Well, that’s complicated… I’ll explain it to you over a coffee.”

He’s chancing, but I’m like, bro, do you think I came down in the last shower? I’m foreign, not stupid. Still, I keep walking and talking with him, because I’m curious and entertained. He’s the first Londoner I’ve met who actually wants to chat!

I ask him where he’s going, and he says he’s going to the betting shop.

Me: “To bet on horses?”

He says no, numbers, luv. He says he goes in there every day and bets 6 pounds. Not like some, who go and sit in there all day, wasting all their money.

His phone rings and he answers. “Yeah mate, alright if I drop by later? Yeah, whatever you’ve got…”

I tell him it’s my second day in London— my first time ever in the Northern Hemisphere. “Where you from then, Australia?”

“New Zealand.”

(This is but the first of dozens of times this will happen in London. To us Antipodeans, Australia and New Zealand are chalk and cheese, and our accents are very distinct, but to the English we’re indistinguishable. They just guess ‘down under’, and Australia’s bigger.)

We exchange names and shake hands and he holds my hand too long. His face is all nose, he’s down-at-heel, and he’s in his 50s (at a guess, though it’s hard to tell), but I’m smiling like Marwood: I can’t seem to stop myself.3

I’m already noticing that I get read differently in this neighbourhood. I'm invisible to certain men— the aforementioned Orthodox men, with their beards and payot,4 their shtreimlech,5 their long black coats.6 I’m not a person to them; I don’t figure in their cosmology at all. The feeling of it reminds me of certain circles at home. It’s a phenomenon where only insiders are real human beings; everyone else is just kind of… not. Conversely, I’ve become more visible to other kinds of men, a keenly gendered attention that takes me by surprise. I’m totally out of practice, on account of how I virtually never experience that flavour any more. It’s uncomfortable and it makes me self-conscious. (Ugh, that’s right, I’m female and you’re not. What am I wearing? What’s my face doing?) When I was young I was always on my guard, but the progressive invisibility of middle age has atrophied my former vigilance.7 My mid-40s-ness grants me a certain freedom— a social neutrality— and mostly at home I walk along with an open face and a happy heart, making eye contact willy-nilly. Before I came I was making jokes about my innocence: Oh Sir, I am but a simple country maid, newly arrived to the city!

Aside from the occasional macking, though, London just feels generally edgier. They’re twin feelings— the feeling of alertness to gendered attention and the feeling of alertness to more equal-opportunities predatory attention (say for the purposes of mischief, begging, or crime)— and the tweak is the same: keep your wits about you. All of this makes me see how I’ve grown to take the benevolence of Wellington for granted. I noticed it when I first moved down from Auckland in my mid-20s.8 That feeling of safety and freedom was one of the main reasons I chose to live in Wellington— long solitary night-walks, not having to watch my back. Putting the armour back on takes a bit of remembering, but it’s a well-worn old skillset, like riding a bike. Anyway, I’m in the habit of paying attention and reading vibes, and that’s a good start on street smarts.

At the betting shop door we pause. “You’re cute,” he says, “Can I get your number?”

I say honestly that I don’t have a phone.

“Well, how long are you around for?”

A week, I say, lying.

“A week?! Then you’re going back? You came all this way for a week?”

I say then I’m going to Yorkshire, which is half-true.

“Why are you telling porkies, then?”9

I say because bro, I don’t know you! and so far you’ve told me you’re going gambling, and done some dodgy dealings!

He give a wounded look, like How could you slight me so?

“That was the food bank, darlin. I go there every day.”

He goes, Can I see you again? I say that we’ll just run into each other another day. That’s how it happens in my country.

“Can I give you my number then?”

I write it down in my book, to placate him. “Andrew,” he reminds me.

“Yes, I remember.”

I tell him I hope he wins. I say that in the normal run of things, I’d have four-leaf clovers in my book, and I’ve give him one for luck, but I’ve left them all at home. Then I continue walking North, convinced I’m walking South and I’ll see the river soon.

Evening in Stoke Newington. I hear music approaching me from behind, coming quickly closer, then a cyclist passes, a black youth with an expression of pure joy on his face. He’s a one-man party, spreading good vibes on his commute. He lifts his hands from the handlebars and extends his arms in full Jesus-pose, as if to embrace the world, then raises his palm high overhead to brush the yellow tree-leaves. Pedalling no-hands at speed, he turns the corner and disappears, leaving a skein of music in the air.

My body, that carries its wound across half the world.10 The face I present to airport security cameras as a requirement of passage. Swapping my skin and bones for the opening of the gate, just like Inanna. The same face as that face encoded in my passport and yet not the same face, as that one is some months old, living in a different house, without felt knowledge of the other side of the world. That self hasn’t watched the names of cities scrolling on the computer screen in the back of the seat in front and imagined them underfoot, a sea floor of land below fathoms of air, a Kermadec Trench of empty space.

The removal of humanness from transit (in the sense of the end of a purely paper passport stamped with ink by a human hand)11 also means the loss of the possibility of cheating or trickery, which seems a true loss to me. I think of The Naked Don’t Fear the Water, how the attempt to board a ship or plane to escape the refugee cage of Lesbos and melt into greater Europe is a roll of the dice, an attempt largely dependent on one’s face, on a kind of passing.

Kev: “I’m basically turning into my Grandad Woollven.12 At the age of 70 he was wheeling a wheelbarrow full of veges round the village— spuds and onions— giving them away to ‘old people’ [makes finger-quotes] who were ten years younger than him. He had like four allotments— some ridiculous amount of ground he used to grow. I reckon he used to garden so much so he didn’t have to go home!”

After extensive explanation— rods, chains, acres etc.— I deduce the following:

1 allotment = 100 square metres.

(Nominally an allotment is four gardenable rods, plus one rod of path / road;

1 rod = roughly 5 x 5 metres / 25 square metres.)

4 allotments therefore = 400 square metres of garden.

Kev’s NZ garden, at roughly 100 square metres = one English allotment.

Conclusion: Kev’s Grandad was a gardening machine.

“He grew absolutely fucken everything. He grew soft fruit… Asparagus… But he grew lots of spuds and onions— probably because they’re staples.”

The reason Kev feels he is channelling his Grandad is that he is also growing too many spuds and onions, so come harvest time he will have to give them away. He doesn’t own a wheelbarrow, though, and his ‘village’ is far more widely distributed, so likely it will be out of the boot of his car.

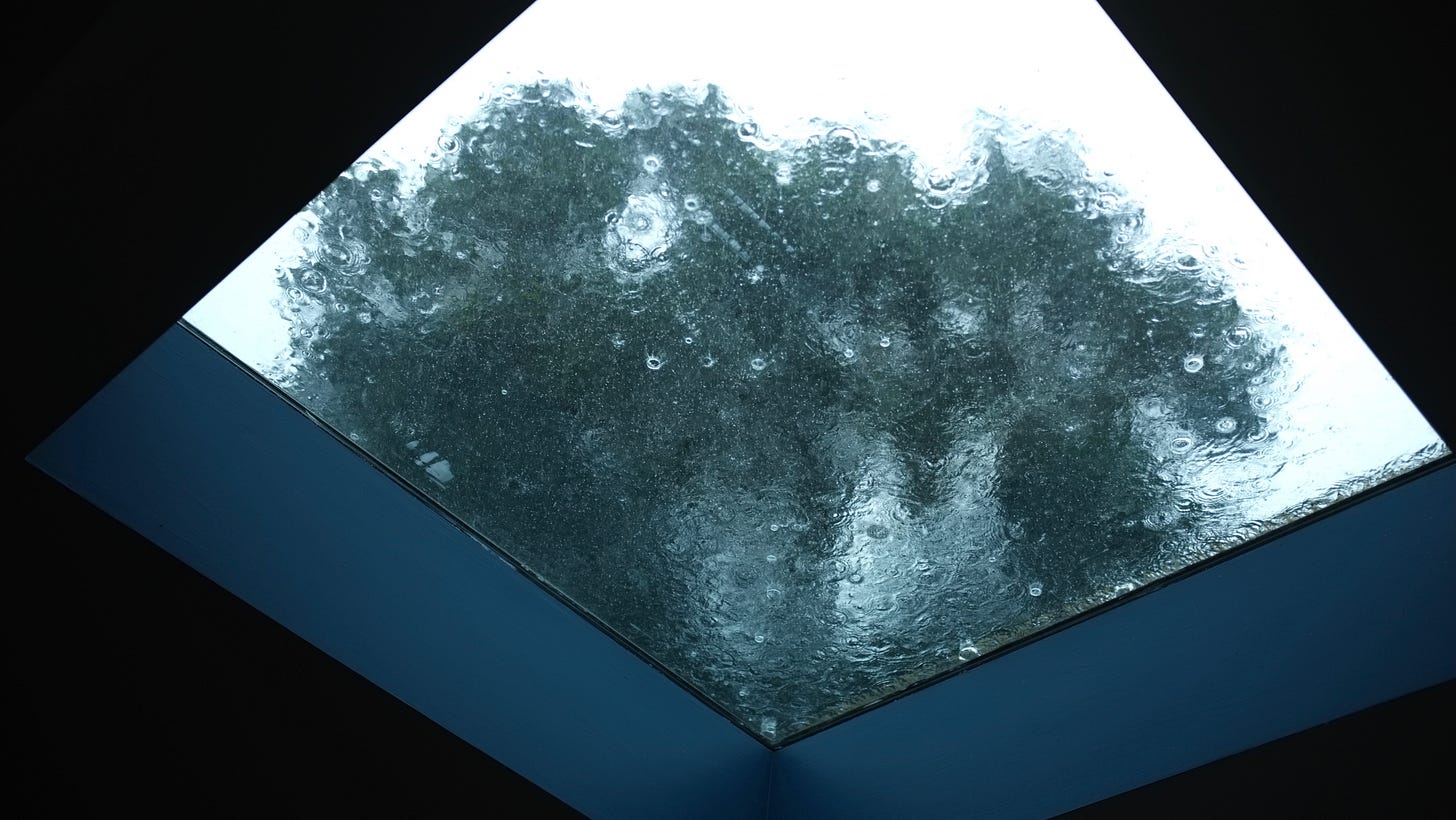

I’m riding the number 1 into the city when I tune in to two boys behind me, a few seats back. Their voices are chill and languid, the almost narcotic affect one hears in some youth, as if there’s no hurry or urgency, as if there’s all the time in the world. The first boy is talking about the huge rainstorm we had.

First boy: “It was like raining in my window and then my carpet got wet, and then it smelled for shit for like, three days.”

Maybe it was another rainstorm, then, because the huge one was just yesterday. I had spent a long indecisive moment standing at the bus stop watching the minutes pass and reading the sky, trying to decide between catching a bus to eat a kebab or just going home. I’d been visiting my old neighbour Steve, who lives on a high hill facing South, and from his living room I had seen the rain-stripes looming over the sea. (The rainclouds come in dark bands— fronts, I guess— that also shadow the sea beneath them, so the seascape becomes horizontally stripy, and sometimes you can see rain falling from the clouds in diagonal drifts. The time between a rain-front’s appearance at the horizon and its arrival on shore is variable depending on windspeed, and it may or may not be dropping rain when it arrives. But it will arrive, and quite soon.)

Me and Steve, watching Jimi Hendrix on the last morning of Woodstock. It’s 8 a.m. and almost everyone has left, so Jimi is facing onto muddy hills covered in rubbish and a small cluster of people who stare at him blank-faced like he’s an alien. Hendrix gives no fucks and shreds the shit out of his guitar, trancing out, dressed in an amazing ensemble of bright blue flares, a white cropped leather jacket with super-long beaded tassels, and a torn piece of pink sari silk tied around his afro. Behind him, a manic bongo player ecstatically beats his drums, his fringe sweat-plastered to his forehead. Behind them both, though, those clouds were making me uneasy. “It’s going to rain,” I said.

Steve said hopefully not imminently, because his washing was out.

At the bus stop, the sky darkened further as the cloud band drew overhead and spread itself out, casting a chill upon me. (I’d come out in a linen shirt, worried about overheating rather than about keeping warm; that’s Wellington in supposed Summer. Wellington dressing is all about layers— add and subtract according to eventuality.) Living by the sea makes you learn the weather, and I was feeling barometric. The temperature and pressure were falling fast. I decided to go home. Once resolved, I walked quickly, increasingly convinced now that the heavens were about to open. I got home, and we all stood around waiting, and then about ten minutes later— boosh! Like a tipping bucket. Like continual tipping buckets. I stood at the back door watching the weather-show. The two big pots that Kieran had been using earlier to preserve the plums were upside-down on the bench outside, and they made a merry metallic raindrop-music. When I said I wondered what it sounded like inside the pots, he ran outside in the downpour to place his phone under first one pot and then the other, to record the sound.

Now the two youths are talking about gaming. “I died like a bunch of times and I lost my stuff. I lost my sword. I lost my pickaxe. I died in an ancient city. The loot in the ancient cities is like, cursed.”

[Describing some game antagonist:] “He’s too powerful. He’s meant to be blind but he can like, smell you. So he’s not really blind.”13

This game chat rolls on and on. “Have you played…?”

“Yeah and, have you played..?”

(For instance, “Have you played Arkham Asylum? It’s like Lego Batman, if it wasn’t made for like… Three-year-olds.”)

Now they’re talking about a friend of theirs who fell off a roof. (I couldn’t tell if they meant in a game, or in meatspace.) “I didn’t go on the roof. I had a sixth sense not to.”

“A sixth sense? Awesome.”

Still talking about the same friend: “He called op shops dirty once then he doubled down like eight times.”

“Yeah, he doubled down— he called op shops dirty and stinky!”

“Flatting with Niko would be horrible, just saying.”

“Did you get your boots back?”

“Yeah, I got my boots back and my pants back.”

They are scheming now about how to improve their lives. “If I got good at like fixing cars? You can buy a broken cool car for so little money.”

“You have to get really good though.”

“Yeah, and mechanics are always covered in oil.”

“Yeah, and you would need like, a garage.”14

…

“Everything just like kinda sucks.”

Shall we get off here, one says to the other, and walk the rest of the way? “I’ve got enough left in the tank, let’s say…”

“If we were attacked by a bear, you might have enough energy—”

As they get off, I sneak a glance. Two thistle-headed sweet-faced urchins, one dark, one fair.

The old Roman road from Londinium to Eboracum (York). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ermine_Street

My first haircut in almost a decade. It wasn’t so much that I had wanted to have ridiculously long hair (with its attendant vibes of high femme, hippie etc.)— rather, its length was emergent from my aversion to sudden irreversible change (i.e. cuts).

Withnail: Anyway he sent me out to say the coffee is ready.

Marwood: I couldn’t drink it. I’ve got a cramp in the mouth from grinning.

Withnail: Well stop smiling at him.

Marwood: I can’t help it, I’m so uptight with him.

Side-locks

Huge fur hats— it’s a Hasidic thing. (A shtreimel is made from many, many tails, and it is a very costly item.)

Actually I dig their outfits a lot: the sartorial formality combined with the fancy hats overlaps with my idea of Wizardwear

I grew up in West Auckland, and my avant-garde compulsion to shave my head / dress like a freak made the hassles ten times worse. (I mean avant-garde literally here: such fashions are fairly normal these days and don’t get you knifed at the bus stop.)

Maybe this relative benevolence is what foreigners mean when they describe New Zealand and New Zealanders as ‘friendly’. We have our dark side, but mostly Aotearoa is less obviously hard-edged and cut-throat.

Actual Cockney rhyming slang LOL

A cut on my thumb

The only time my passport got physically stamped was in Barcelona. (Sad!)

Woollven means ‘Wolf-friend’ in Anglo-Saxon. Later on Kev told his brother that he was “LARPing Grandad Woollven”.

That made me think about John Goodman’s Polyphemus, Big John Teague, in O Brother, Where Art Thou? which I just rewatched the other day. I guess because Odysseus totally blinds Polyphemus. But there are two other blind characters in that film. Lee Weaver’s Tiresias: he’s the old man driving the railway handcar (Kev was shocked that the three young men sit on the handcar without immediately taking a turn at the labour of cranking it); and the radio DJ Mr Lund, played by Stephen Root, who corresponds to Homer hisself.

Pronounced the American way, guh-RAAJ.

London was the only place I was in last year where my age (crone) and outfit (crone couture) didn’t work as an invisibility cloak. Maybe something in the air.

us two will need to talk about Wizardwear one day.