Isn'tness Theory

Words Without Pictures, Ursula K. Le Guin, & the Pure Mind-Meld

Shevek: “Well, we think that time ‘passes,’ flows past us, but what if it is we who move forward, from past to future, always discovering the new? It would be a little like reading a book, you see. The book is all there, all at once, between its covers. But if you want to read the story and understand it, you must begin with the first page, and go forward, always in order. So the universe would be a very great book, and we would be very small readers.”

(Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia)1

“Eternity is in love with the productions of time.”

(William Blake, Proverbs of Hell)

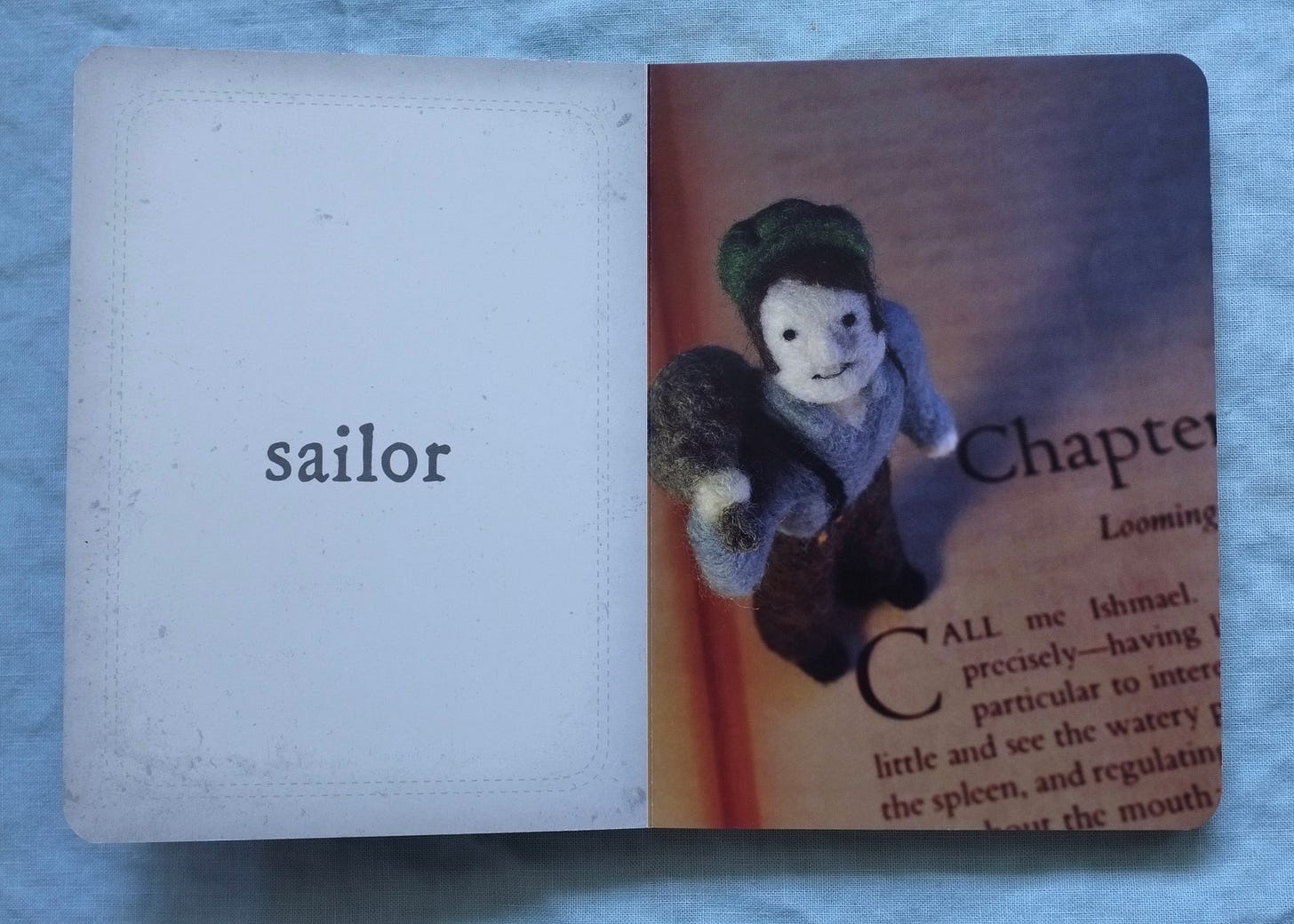

A child discovers a trick. Opening the cover of a book is opening a door. The child opens the door and steps through it into another world. Every book is a door, every library a galaxy of portals. (The wood between the worlds.) There must have been a time before I could read, before I learnt that magic trick, but what I want to talk about is the 40-something years since I became literate— my life as a creature of the word. I want to talk about how it feels to meet on the page.

When I was little I was in love with books. I was one of those kids who is never not reading. There was no end to my need for words. They were my solace, my heart’s salve, my mind’s food. Rebecca Solnit put it this way in her essay Flight: “Like many others who turned into writers, I disappeared into books when I was very young, disappeared into them like someone running into the woods.”

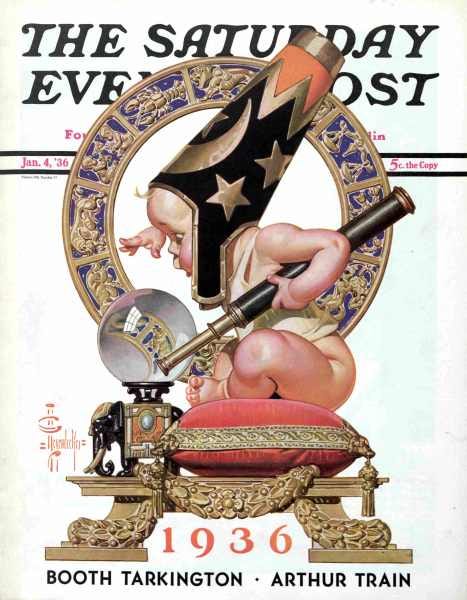

When people asked me the question big people ask little people— What do you want to be?— I said, I want to write books. And illustrate them. That is to say, books were supreme magic to me, and as soon as I understood that books were made by people, I wanted to be a practitioner of that magic when I grew up— I wanted to be a Magician.2

Solnit again: “What surprised and still surprises me is that there was another side to the forest of stories and the solitude, that I came out that other side and met people there.”

You know that phenomenon— say there’s a book you love, a book you’ve read dozens of times, and then you see a movie of it. Or say someone has described a person or a place to you repeatedly, lovingly, then you meet that person or go to that place. (Me, recently, England.) Whatever was imagined— be it decades-worth of interior weaving— is gone. The solid reality ousts the delicate imaginal structures. They melt in an instant, and they can’t even be remembered, let alone reconstructed: when you think about Frodo or Galadriel now, all you can see now is Elijah Wood and Cate Blanchett… forever. In the world of words, the image is a blunt instrument.

Think about a beloved character, let’s say Shevek from The Dispossessed. Shevek is described in the book— he is tall and thin, with large ears and fine fur— but his image is not fixed in my mind: it’s not something I see. Yet I see him.3 He is a person I know. If, by some chance, someone were to make a movie of The Dispossessed, I know better than to watch it. The imaginal structures I’ve built on the foundation of that text are too central to my thinking to be tampered with.

This magic of naked words (words without images, words that generate interior imagery) is most apparent in the world of fiction. That’s not my world as a maker— I’m too interested in quote unquote reality, non-fiction4— but it is the magic that got me deep-hooked on words in the first place.

Le Guin, in her essay Teasing Myself Out of Thought,5 makes an analogy between writing and ceramics: she compares the writer to a potter, the work to a well-made pot. Don't fill the pot up, she says— that’s not your task. It’s a Taoist metaphor to choose, and indeed, she is talking about negative capability: “A poem of the right shape will hold a thousand truths. But it doesn’t say any of them.”

Because “What my reader gets out of my pot is what she needs, and she knows her needs better than I do. My only wisdom is knowing how to make pots. Who am I to preach?”

Against isness, isn’tness: Yin, shadow, emptiness.6 Stepping into a cool dark room, after walking a long way in the blazing sun. Welcome, friend— sit here— drink this water! (The water is drawn from a well. It tastes like stone.)

My shorthand phrase for this phenomenon of literary immersion in the imaginary was the mind-meld, until I realised the Vulcan connotations. (Did I pick it up osmotically?) Meld is a melting-word, a muddling or meddling word, a dissolving-of-boundaries word. Its origins are uncertain (the OED suggests perhaps a blend of MELT and WELD?) but it is associated with card-playing: the declaring of cards.

I had been thinking about books-without-pictures (chapter books, in the vernacular of children’s literature), but then I dreamed I was wearing a ballgown with a motif of Beatrix Potter watercolours. I woke and remembered how— when I was very small— the words and the pictures in a book were themselves melded, an indistinguishable whole. I can remember the delight of illustrations, their aliveness: Peter Rabbit was Peter Rabbit, Moomintroll was Moomintroll, the character made of words and pictures blended. (Chosen at random— but both of these characters are written and drawn by a single maker. There are also inspired marriages of writer and illustrator: A. A. Milne and Ernest Shepard, Roald Dahl and Quentin Blake, etc.)7

But then, I can also remember the wrongness of certain illustrations. There were illustrators I disliked when I was small (generally because I found their work ugly), but I associate this feeling with Young Adult book covers in particular. I liked to read historical fiction, which often came in the form of cheap paperbacks. Sometimes the only image was on the cover, and very often it didn’t match my conception of the character(s) pictured. I’d feel like, Did we even read the same book? And— there— I can pinpoint the emergence of a literary consciousness, a supremacy of the imagination. My internal picture was threatened or damaged by some cover artist’s hack job: I had been weaned off imagery.

What I’m talking about, then, is more specific than whether a book is illustrated or not. What I’m really talking about is the invisible wizard behind the curtain. I’m talking about the author’s voice. I’m talking about the way in which a reader knows a writer, and the place they meet.

I write, and writing is a kind of magic. You read, and reading is a kind of magic. Our minds meet on the page, and that’s another kind of magic. My mind makes pictures in yours. From the point of view of the page, this happens simultaneously. The book (or in this case, the essay) is a co-created world. From the point of view of the reader, this world is an internal, imaginal realm. They're your pictures, your structures, and I can never see them: nobody else can. You could try to tell me about them, say by writing them down— then you'd be a writer too.

This meeting of the minds can happen across vast distances of time and space. I can read Herodotus, dead for 25 centuries, yet he is alive on the page: his voice still speaks there. From the point of view of Herodotus, there’s no way he could imagine me. Extrapolating from that, how can I know what happens to my words once they leave my pen? There’s no way to know. Yet I speak here.

Writing is opening your house up to strangers. It’s building a house, and leaving the door unlocked. It’s an act of hospitality and trust.

In The Left Hand of Darkness, Le Guin’s word for telepathic communication is bespeaking; that’s good, but too directional. She says in her essay Telling is Listening: “Transmission via print and the media is one-way; its mutuality is merely virtual or hopeful.” But she also describes speech as an act of intersubjectivity, as amoebas having sex, and that’s more like it. Even though I’m talking about reading, seemingly a one-directional act, intersubjectivity comes close to what I’m trying to describe.

When I read a book, I prefer not to know what the writer looks like. I try to resist turning to the back flap— to the author photo— at least until I’ve finished the book. Sometimes I give in and look. Often they look nothing like what I expected. Sometimes I’m pleasantly surprised, say the author looks cool, or has an interesting style. But far more often I regret looking. Something has been lost— that’s how it feels. The pure spaciousness of mind-to-mind knowing has been traded for a small piece of seeing.8

There has been some debate in the town square recently about young people showing their bodies off— about, I guess, the emergence of Sexstack. Reading some of that debate, I thought, no, they have it wrong, those arguing people. They’re arguing on the wrong ground. It’s not about gender, or freedom, or honesty: it’s about subjectivity. The body is real, but the mind is another kind of real. When I read someone’s work and I have no idea what they look like… To me that’s a beautiful scenario. In that regard Substack has felt like the very early Internet, when there were only words, no images. It has felt, indeed, like a book.

I wrote recently, in response to a post about ye old days by

: “I remember (and what an old-person opening that is) the shock of seeing people for the first time who previously I’d known only as disembodied voices… Radio, records, I mean. There’s something beautiful about knowing someone only through their voice.”What is it to know someone only through their voice— whether that’s their singing or speaking voice, or their writer’s voice, their voice on the page? To know someone without knowing what they look like— yet to know them deeply, in this particular intimate way, mind-to-mind— is a profound experience, a communion, a symbiosis. The person singing or writing is singing to you, although they don’t know you. They are singing into eternity, trusting that what they make is well-crafted, trusting that it will be received. (When I was making daily drawings I used to call this paper planes into the void. I try my best to make something good, then launch it forth. Very often little or nothing comes back to me, but I trust it will land somewhere: it will be received.)9 As Robert Louis Stevenson (who had been a bedridden child obliged to build castles in the air), put it in his poem Where Go The Boats:

Away down the river,

A hundred miles or more,

Other little children

Shall bring my boats ashore.

It’s customary at the end of the year to consider the year. When I think about my 2024, I see the major evolution was this: my web of connection grew larger and more complex. I started addressing strangers. Now that my audience is bigger than my known world, return messages are far more frequent. Paper planes and boats fly and float back out of the void far more often. (Back-eddies, I guess.) That reciprocity has been a transformative gift.

Barry Lopez says: “It is not a thing, Eden, but a pattern of relationships, made visible in conversation. To live in Eden is to live in the midst of good relations, of just relations scrupulously attended to, imaginatively maintained through time. Altogether we call this beauty.”

There are things in the world of words than cannot be made into images. Yet when I write I use images too: I can’t not, after thinking that way for so long— thinking as an artist, visually. My mind is a braided river system. I am interested in the way words and images speak to each other, and the dynamism generated by that dialogue. I am interested in how images generate words, and words generate images. (Ekphrasis; reverse ekphrasis / illustration.)

But I am not very interested in how people look. I am— we are— sated, stuffed, saturated with that kind of information: the reduction of a human being to their skin, their appearance. That’s only a fraction of truth. That’s the propaganda-world we’re all forced to live in, a world where our eyes, those sacred windows, are considered just an opening to hook and sell us by. The world is full of forces seeking to control even the shape of the imaginal structures we build in the privacy of our secret hearts. Being seen that way, as prey for parasites, is insultingly reductive; but worse than that, that way of seeing seeks to make us see our fellow humans that way— to limit our understanding of what other people are, of what we ourselves are. Yin is the antidote to that pathological Yang. Not-knowing / not-seeing is a fertile lacuna, an isnt’ness. Isn’tnesses are an endangered species in these Panopticon times.

That’s why, in my own work, I don’t describe what people look like. It’s also why, when I arrived here, I resolved not to use photos of myself. I’ve since softened that rule, but I grappled with the decision for days. I reasoned that photos of me exist elsewhere on the Internet, but it still felt like capitulation. Why such strong resistance to showing my face? Now I understand that the ephemeral thing I was trying to hold onto was the ideal of the pure mind-meld. 10

I have friends on here whose faces I’ve never seen, and that’s a beautiful state of affairs. Minds are just as distinctive as faces, but the difference is that minds are self-created; the flexibility, capaciousness, distinctiveness— the character— of a mind is the fruit of a person’s labours. People love to impose meaning on faces, but that seems unfair. Faces are random, a roll of the dice, the luck of the draw. You can tinker with the face, sure, but you can’t really alter its lineaments. In that regard, the mind is a more accurate measure of a human being.

Because word-immersion is a feeling I associate with childhood, the past, and purity, reverting to the mind-meld as a mode of communication feels like going backwards— it feels like swimming against the stream of history. It’s refusenik. I think that’s why Substack feels retro, and why it feels like an aberration in the modern world. It is literary to know people by their minds alone: I’d go so far as to say intellectual communion is the heart of literature. Writing contains multiverses that are irreducible to any other form.

In The Dispossessed, Le Guin writes a physicist. Her protagonist, Shevek, is trying to distil a General Temporal Theory— to blend Sequency and Simultaneity— so that the ansible (a communication device) can be invented, so that Le Guin’s Hainish universe can work.11 Shevek’s idea is bigger than his Anarchist world. The book shifts between timelines— it is braided— because it concerns conceptions of time. Like a symphony, its form is fractal. On one level, The Dispossessed is a study of the work: creative labour / intellectual freedom. “He was the free man: he could do what he wanted to do when he wanted to do it for as long as he wanted to do it. And he did. He worked. He work/played.” I understand that in describing Shevek’s work processes, Le Guin is talking about physics; and simultaneously I understand she is talking about writing. I understand that Shevek is Oppenheimer and he is also Le Guin and he is also me. He is a person— a character— the elegant vessel of ideas.

None of this, though, explains the magic of imaginal immersion. It’s a felt place. Trying to explain it is like trying to dissect a living animal to understand it. That’s why The Dispossessed is a masterpiece— it’s irreducible. Why is the written word magic? It’s magic because it’s real in a particular interior way— it’s real to me in my way and to you in yours. And yet it is black marks on the white page. (See? Sequency and Simultaneity.)

Negative capability / Yin / Isn’tness

Isn’tness is always harder to see than isness. That very unseeability is its nature.

Ideas are wild animals roaming the mind’s forest.

It’s not possible to force inspiration (or magic). All you can do is make space and time. If conditions are correct, wild yeasts might come and animate your dough.

There must be a boundary— the edge of the work— that defines what is inside and what is outside the parameters of consideration. But the work is a large container, more capacious than it looks. Make space.

Fiction is making worlds that generate interior worlds. Non-fiction is an anthropology of self, a study of the interior world.

Isn’tness-thinking encompasses uncertainty, paradox, metaphor. The ostensible subject is not always the real subject. Name things by naming other things.

Simplify in order to understand. In a world saturated with stimulus— much of it horrifying— turn away, close your eyes, retreat. Undo, unlearn. Silence and solitude are isn’tnesses.

Don’t throw your energy away. Fighting is capitulation, implicit submission to someone else’s terms. (Le Guin: “To oppose something is to maintain it… You must go somewhere else; you must have another goal; then you walk a different road.”)

Make something instead.

Come home. Step inside yourself. Claim your birthright: subjectivity.

Being looked at is one kind of real— but what’s more intimate than being inside someone looking out of their eyes? There are other kinds of nakedness, is what I’m saying.

“It's nothing to do with eternity," said Shevek, grinning, a thin shaggy man of silver and shadow. "All you have to do to see life as a whole is to see it as mortal. I'll die, you'll die; how could we love each other otherwise?”

Full text here (some transcription errors):

The Dispossessed

I guess that means I’m now a grown-up

Maybe more like the way a dolphin ‘sees’, by echolocation: as well as the outside of another dolphin, or a human, they see the inside, the bones and organs. They can tell if someone’s pregnant— they can see the baby.

Non-fiction is an isn’tness-word; a genre that defines itself as not-something.

Excerpts are a poor substitute for reading Le Guin’s essays in full, but the essays, like most of her work, are not available on the Internet. You’ll have to go to a library.

The High Priestess; that which can’t be known

Respect to those who don’t include a photo. Fitzcarraldo Editions eschew imagery entirely: none of their books have a cover image or an author photo.

Walt Whitman directly addresses his future reader:

“Whoever you are, now I place my hand upon you, that you be my poem,

I whisper with my lips close to your ear,

I have loved many women and men, but I love none better than you.”

I have written about this before…

When I started writing here almost a year ago, (I wrote,) I noticed an interesting phenomenon: I was experiencing the new form of intellectual labour as a blessed relief from what I had started disparagingly referring to as the World of Matter…

I have realised that part of the reason I feel so comfortable in the space of being a writer is that I get to be a mind expressing itself separate from body or face.

Brain in a Jar

Adrienne Rich in 1977, quoting Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre: “I have an inward treasure born with me, which can keep me alive if all the extraneous delights should be withheld or offered only at a price I cannot afford to give."

Shevek explains the ansible: “It will be a device that will permit communication without any time interval between two points in space. The device will not transmit messages, of course; simultaneity is identity. But to our perceptions, that simultaneity will function as a transmission, a sending. So we will be able to use it to talk between worlds... It is really a very simple matter.”

I think of this "how can I know what happens to my words once they leave my pen? There’s no way to know. Yet I speak here."... And I think of one of the most moving experiences as a teacher I've ever had: with a university class, we were discussing "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry" by Walt Whitman, and these lines and following:

"And you that shall cross from shore to shore years hence are more to me, and more in my meditations, than you might suppose."

And I said to them, "look! He is writing this over a hundred years ago, but he sees us! He is thinking of us! He is speaking to us directly and we are in his mind as he is in ours!" .... It felt like the most profound moment of explicit contact across time and space through literature. Yes, we set our paper-boats a-floating, not knowing where they will come home. But we may pitch our sight, by a magical act of the imagination, to see them land, to see them gathered in, on other shores far down the river....

…experiencing someone creatively definitely feels more intimate than looking at a picture of their ass…it is beyond cliche to call substack only fans but words at this point but fitting also it is starting to get infiltrated by those whose creativity is ass photos…the paying world values us more as objects…less as ideas…