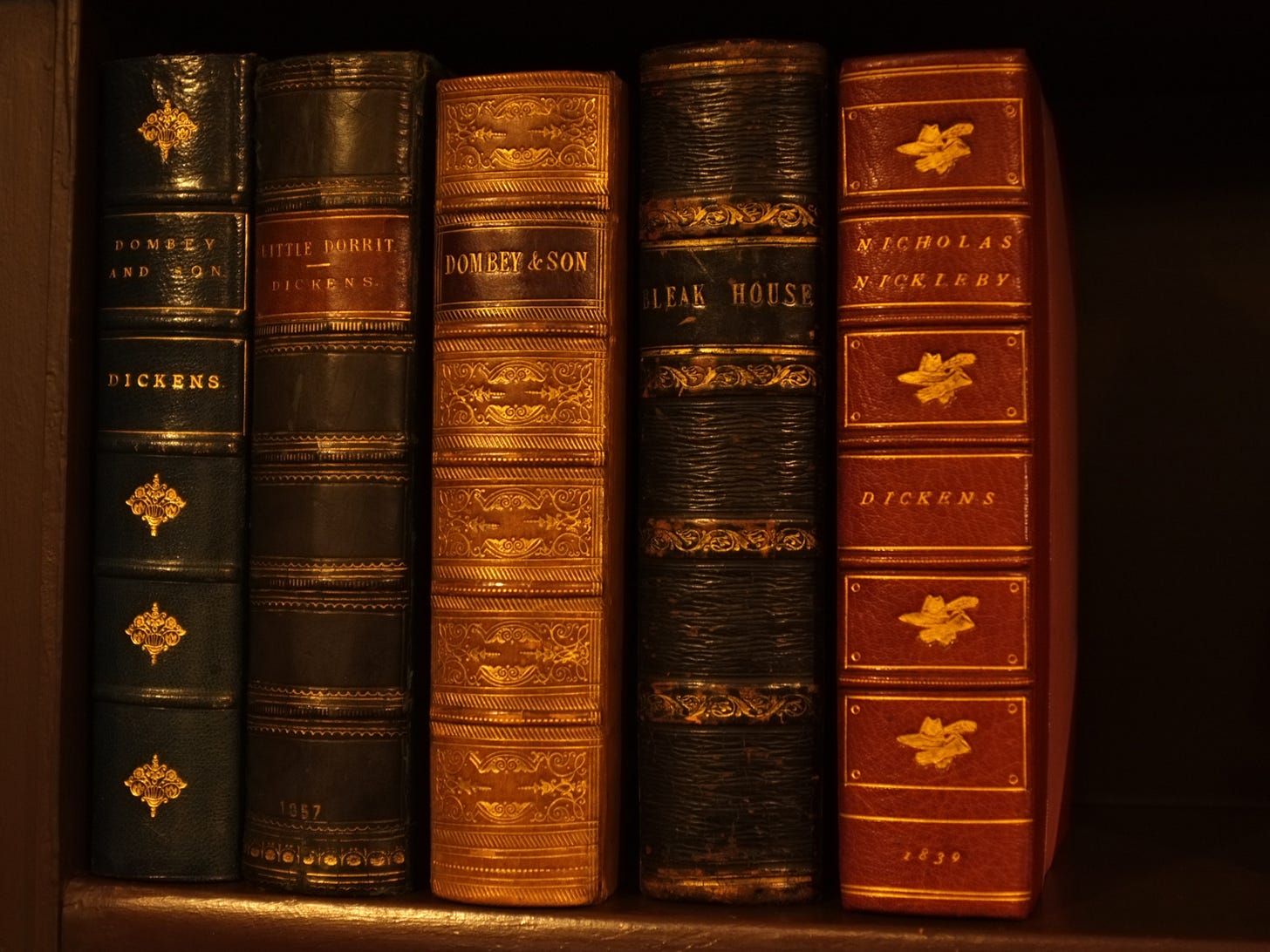

Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol: “It was his own room. There was no doubt about that. But it had undergone a surprising transformation. The walls and ceiling were so hung with living green, that it looked a perfect grove; from every part of which bright gleaming berries glistened. The crisp leaves of holly, mistletoe, and ivy reflected back the light, as if so many little mirrors had been scattered there; and such a mighty blaze went roaring up the chimney as that dull petrification of a hearth had never known in Scrooge's time, or Marley's, or for many and many a winter season gone. Heaped up on the floor, to form a kind of throne, were turkeys, geese, game, poultry, brawn, great joints of meat, sucking-pigs, long wreaths of sausages, mince-pies, plum-puddings, barrels of oysters, red-hot chestnuts, cherry-cheeked apples, juicy oranges, luscious pears, immense twelfth-cakes, and seething bowls of punch, that made the chamber dim with their delicious steam. In easy state upon this couch there sat a jolly Giant, glorious to see; who bore a glowing torch, in shape not unlike Plenty's horn, and held it up, high up, to shed its light on Scrooge as he came peeping round the door.

'Come in!' exclaimed the Ghost. 'Come in! and know me better, man!'”1

It’s the strange destiny of a New Zealand Pinus radiata to be scorned and despised for eleven months of the year, then lauded, bedecked, and glorified for the twelfth.

After I wrote that in my journal, though, I realised that not everyone hates pines. The sight of a formerly bush-covered hillside bristling with lines of dark-green pine-children (they are planted in straight lines, which makes them look just like scissor-cropped doll’s hair) probably gladdens the mercantile heart.

Commercially grown pine wood, the kind you get in Bunnings, is the plastic of the wood world. The logs you see stacked on trucks have been milled into cigarette-shaped tubes. These are sliced into 4×2s and marinated in green or pink chemicals, the woodchips mixed with glue and Gods-know-what to become MDF or Weetbix-board. One could say, then, that the pine-as-Christmas-tree is not opposite to this usage at all, but rather a variant of the same drive: a vegetative symbol of pure commerce.

Poor little pine trees. They didn’t ask to be born!

The other day when Keiran came home from the studio we sat in the living room and listened back to his day’s music, made with Ruby and plants. (He has a project called vegetable.machine.animal, that involves making plant-music by means of passing their electrical signals through a modular synthesiser: as I understand it, it’s a collaboration with the non-human world.) The music was beautiful, random, and spacious. I could hear Ruby close to the microphone: I guessed she was tapping bones, using her mouth as a resonating space, and further away I could hear Kieran’s drums. Then a low note came in, like a humpback whale’s song. “That’s the geranium,” said Kieran.

LOL!

Me: “Did you use the same plant all the way through?”

Kieran: “The geranium on the first two tracks, then a lichen on the third.”

We had talked earlier in the day about his hatred / my love of Christmas carols. I said that me and Kev sing a few, mostly shepherd-themed. (We didn’t plan it that way, but it works in well with our other sheep-related repertoire, of which there is plenty, concerning both the tending of and the thieving of: dog songs and wolf songs, if you will.) I said I’d recently been singing While Shepherds Watched to the original tune.2

“It goes—”

“NO!” said Kieran.

Passing by the Christmas tree on my way to bed— a small pine, as yet undecorated— I said to Kieran, “Have you tried talking to a Christmas tree? Do you think it would be… maybe… festive?”

Kieran: “Nah— black metal, I reckon.”

Before I went to London, people said things to me like Why are you going in Winter?! And Well, I guess you’ll get a taste of English Christmas. The implication was that New Zealand Christmas is not Real Christmas, which is a correct implication. Like the rest of our imported festivals, it happens at the arse-backwards time of the year: high Midsummer.3

The other implication, though, is that everyone loves Summer and hates Winter— incorrect. When I was due to come home, people said things to me like You’ll be going back to Summer! And holidays! as if this were an undeniably wonderful thing.

I said “I hate Summer. And holidays. I only like Winter and work.”

It was kind of true, though, that English Christmas made seasonal sense.

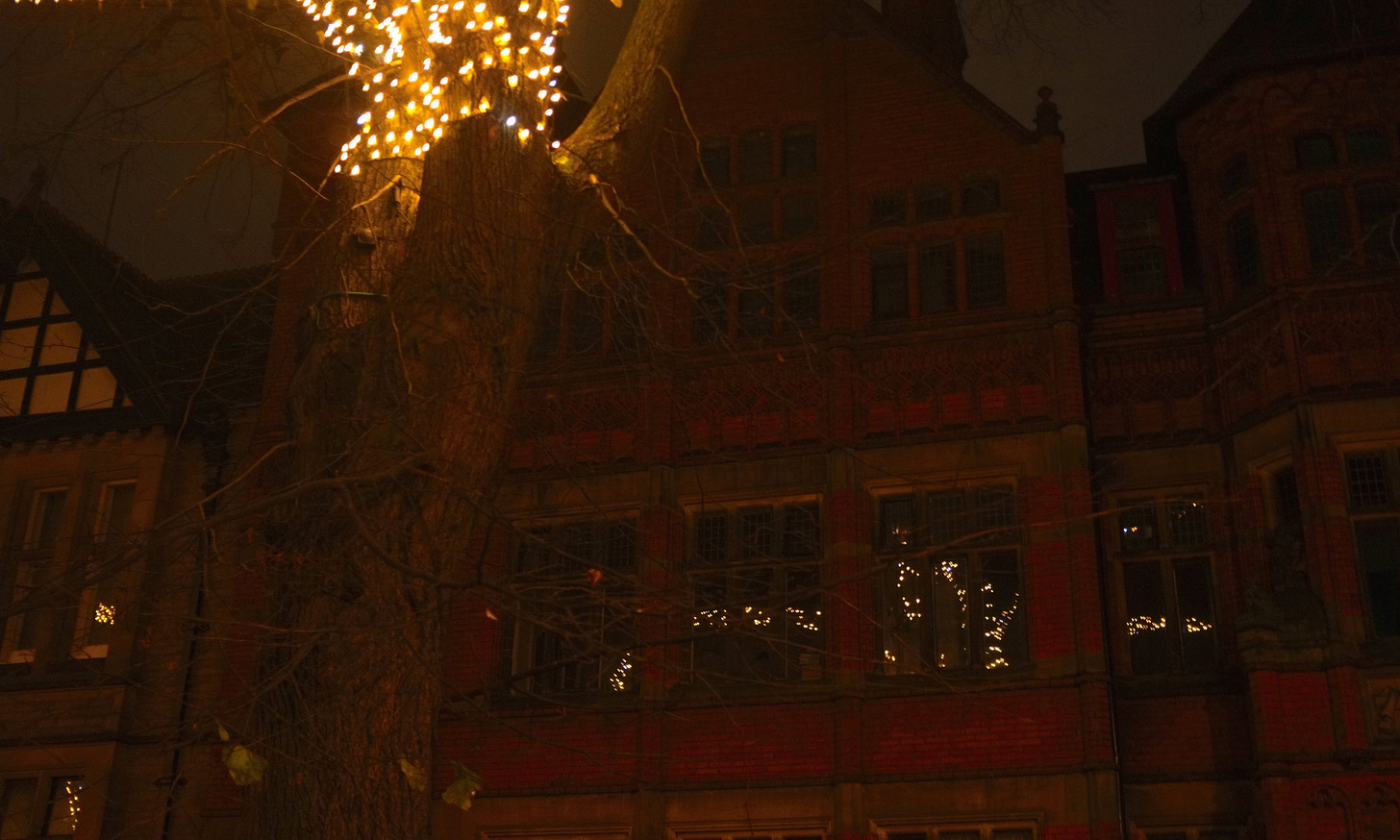

One grimly cold night in early December, I found myself at London Bridge station with unexpected time on my hands. (I was on my way back from Brighton to meet someone, but they cancelled.) Out! At night! In the city! Whee! I hadn’t been out much at night, and I felt it was time for an historic pint. I searched oldest pubs London. There was a whole list of them, but one name jumped out at me: Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese. It had featured in the Alan Moore novel I’d just finished, The Great When: Dennis Knuckleyard, the protagonist, meets his journalist friend Tolerable John there. As good a lead as any. I walked through the light-studded drizzle towards Fleet Street. I was almost there (according to the breadcrumb-trail of blue dots)4 when I spied a church off to the side. I like a good church, and something seemed to be happening, so I went down the alleyway and up to the church door— it was Saint Bride’s— where two people were waiting. They said that tickets for the imminent carol service had been drawn by lottery from among subscribers to The Times, but they were pretty sure I could get in if I came back just before it started and tried my luck.

I walked the few blocks to ye Cheshire Cheese, dodging the perfume-salesmen who tried to accost me outside. Finding the way in was a puzzle in itself— there was a map on the wall with arrow-trails showing which alleys to follow. After some wrong turnings and step-retracings, I finally found the inconspicuous door. Inside: dark wood, small rooms, logs burning in open fires. The tiny, ancient front bar was standing room only, but the place was a warren of sub-pubs, five or six of them joined together by little corridors and stairways. After sticking my head into the restaurant bit (which had a portrait of Samuel Johnson on the wall: it was one of his hangouts, apparently) I went downhill to the capacious bottom bar and ordered a cider. It was after-work time, and everyone down there seemed to know each other. I didn’t want to be a no-mates, and I wanted to be close to the little front bar, which I judged to be the oldest part, so I carried my pint carefully back upstairs to the narrow hallway outside the front bar,5 which had long benches inset into each wall. As well as the benches, there were little shelves to put your drink on. I liked the economy of space implicit in turning the hallway into a tiny room. Every square foot counts!

I got talking to a man whose friends were late. He told me that because the Thames washes everything downriver, I should go mudlarking at Erith, where he was born. We talked intensively about London history, then I asked him what he did, expecting him to say he was a professor or a journalist— but he said he was a [board secretary? anyway, some extremely corporate job involving advising large corporations, some eviler than others]. This kind of thing happened all the time in London; I was getting used to it. Then his friends showed up and ignored me entirely, so I skulled the last of my cider and wandered back down to the church, quarter-cut on cider and, as they say, merry.

I walked boldly up to the doorfolk and asked if I could come in, saying the person I talked to before said I could. They let me through. The service was about to begin, so I walked quickly over the underfloor Dead and took my seat by some fairly dressed-up people. I wasn’t dressed for church because I had come straight from my day. I was wearing my Brighton outfit: my usual, boots, jeans, and a waistcoat and jacket, not exactly shabby but pretty… vernacular. It was also possible I smelt of cider. (Yes, I AM a peasant, what of it?) To my left there was a small altar bearing photographs of slain journalists. The Times was a signifier I didn’t entirely understand, but I knew enough to know I was in a nest of Tories, but so what. Pure chance had led me to this wonderful circumstance, and besides, this was what everyone was on about, English Christmas. Bring on the choir! I sat there bubbling with anticipation, thinking of my Dad— how he would have loved it!— the pomp, the music, the old square whiteness history of it all.6

Up in the lofty ceiling of the church was an effigy of a golden Goddess in flowing robes whom I took to be Saint Bride. This was pleasingly pagan, and when the rector got up to speak, she had a silver crew cut and an air of gender-fluidity. (After the service I asked her who the other statue was, and she said it was Saint Paul. Saint Bride’s is in the vicinity of Saint Paul’s, so maybe he’s the general patron saint of that bit of London? Saint Paul is a dick, in my view, for smashing up the Temple of Many-Breasted Artemis at Ephesus,7 so I liked it that in here he was secondary to a female Saint / Goddess.)

When the choir started I realised that I wasn’t going to see them. They were hidden behind a row of pillars, voices without faces. They were sublime, though, and tears fell from my eyes at the pure beauty of their harmonies. At the end of each song they would crank up into full volume counterpoint for a climactic final verse, which was fucking exhilarating.

In between songs, people read things. A man read a poem by Benjamin Zephaniah (a Black Anarchist) about refugees. A woman in a sequined top and pencil skirt read out the bit about the angel Gabriel telling Mary she’s knocked up. OK, OK, fine— the Annunciation.

(The angel went to her and said, “Greetings, you who are highly favoured! The Lord is with you.”

Mary was greatly troubled at his words and wondered what kind of greeting this might be.)

This story always reminds me of high school art history. I see the scene taking place in a small box-room with the front cut away: lilies and gold, wings and halos, words issuing from the angel’s mouth on a ribbon.

In my enthusiasm I had forgotten that I can’t sing church music. They always pitch it in a place that’s impossible for me: women are meant to sing soprano in church— not my range. But I was happy to listen. In the row in front of me were three angel-faced teenagers. I wondered if they were ex-choirboys, cast out of soprano Paradise.

Afterwards everybody went to the back of the church for mulled wine and Christmas snacks. I held my warm glass up to the rector, like Congrats bro! Great job! This seemed to affront her, but she grudgingly cheersed me back and answered my questions about Saint Bride. Servers brought jugs of hot wine around to top everyone up, and platters: Parmesan and herb shortbreads, tiny sausages wrapped in bacon. I got yarning to a couple when the woman told me that the choir had made her weep and I said, me too. He was a journalist named Miles and she was a film-maker, and they were very interesting and nice, and we stood there chatting and sipping our mulled wine, in the warm smell of spices and resin. My heart was happy. I was a waif who came to the door, and they welcomed me in and fed me, and that’s the way it should be.

When I got home I stepped into another bubble of beauty, out of the cold and into the peace of the warm house. Little one was asleep, and Maddy was sitting in the beautifully lit living room practising carols on the harp. When she paused in her practice, I played her this one:

Why does it sound that way? Maddy asked. We discovered by means of Wikipedia that it sounds that way because the carol contains a Picardy Third. The music for it was in her harp book, and she flipped to the page and started to pick the tune out. Fingers, strings, and her concentrating face in the golden light. The Coventry Carol is a little scrap of the past: a surviving song from a mystery play, first written down in the 1500s but possibly much older. Who can predict what will survive Time’s annihilating river?

I started this piece intending to write about all the reasons I hate Christmas. It was going to be a bitter anti-Capitalist rant called ‘Why Christmas Sucks’. As pre-Ghost Ebenezer Scrooge puts it, “If I could work my will, every idiot who goes about with 'Merry Christmas' on his lips, should be boiled with his own pudding, and buried with a stake of holly through his heart.” I mean… That’s the beauty of writing, right? Discovering what you actually think about things? As I’ve ended up writing about Christmas music, though, let me return to the original spirit I intended and name something I loathe with all my being: the saccharine cover versions of American carols one is forced to listen to in places like supermarkets and shops. You know the songs I mean, chestnuts, sleigh bells, snowmen, sexualised Santa and so on and so on.8 Every time that shit is forcibly funnelled into my ears it feels so filthy, and I’m only listening to it: I’m honestly boggled by the fact that any singer can perform such an atrociously cheesy abomination with a straight face. Maybe the singer breaks down in tears of humiliation afterwards, or maybe they go get drunk and count their money.

Even sleigh bells aren’t beyond redemption, though. I was in Newtown library the other day when a little kid started singing on the other side of the room. “Jingle-bells-jingle-all-away,” they sang. The tune they made was an incantation, an enchantment; a line of chant that rose then fell, bearing scant resemblance to the tune most of us know and hate. They were getting louder, varying their homemade melody slightly, like a tiny jazz singer. “Jingle-bells-jingle-all-away, Jingle-bells-jingle-all-away, Jingle-bells-jingle-all-away…” If only I could write music— I thought— I could write down the tune, because there’s really no way to describe a song in words.

I couldn’t see the kid, only hear them, but I guessed them to be about two: zero self-consciousness, only the newfound joy of song in their little heart. They were the Newtown equivalent of the Saint Bride’s choir, embodying the Christmas spirit with their whole being; and like the choir, I couldn’t see them— they were a pure voice to me. The kid was winding up to a triumphal peak now, the same but louder: “JINGLE-BELLS-JINGLE-ALL-AWAY!”

The whole library was listening, and I half-expected applause, but instead we just turned and smiled at each other, and it was a Very Good Thing.

December in England was naked black branches against a grey sky; austere, bare tree-bones. The light in England was subtle and mild. Nobody wears sunglasses there— no need.9 When I first got back to Wellington, the colours felt so psychedelically bright they hurt my eyes; the saturated greens of the Summer vegetation, the cerulean sky. Then the rain set in. Last night— Solstice Eve— the sky cleared for the first time in a week, and I found myself standing on my new balcony taking pictures of my new view. Green hillside, golden lights in the little houses on the ridgeline, opalescent clouds in the darkening sky. Beetles came humming in the air, trying to fly inside to my light, and I gently blocked them with my hand.

This morning I opened the curtains to the full face of the Solstice sunrise. Dropping my eyes from its radiant magnificence, I noticed properly for the first time (like I said, it’s been raining and / or blowing a hooley all week) the large pōhutukawa trees in the street below. Because my new residence is elevated, I am looking down upon their crowns, which are bursting into flower: bright blood-clots. Each tree blooms at its own pace— pōhutukawa are individualists like that— so that some are half-blooming, some are fully blooming, and some are yet to bloom, still covered in a lacy shawl of grey buds. (Christmas Past, Present, and Future.) December in Wellington is scarlet. Happy Solstice one and all!

It’s a way better tune than the usual dreary hymn— most people know it as the tune to On Ilkley Moor Baht ‘at. While I was in York I was going around humming the carol, until I realised that humming the tune without the words is basically just humming Ilkley Moor… whilst in Yorkshire… shame!

I was going to keep this one secret, but after a few outings I’ve realised it’s too difficult for most people to transpose lyrics and tune on the spot, even if they theoretically know both, so here you go. Merry Christmas. Learn it and we’ll sing it together!

My main problem with Southern Hemisphere Christmas is how historically (by which I mean Pākehā-historically) it has drowned out Summer Solstice, the actual energetic high point of the year. Seasonally appropriate festivals are powerful ancient magic, which makes seasonally inappropriate festivals bad backwards magic. (See also: Springtime Hallowe’en, Autumn Easter, etc.)

The peril of backwards magic is a seasonal crank of mine, and I knew I’d already written about it last year. Searching Christmas turned up this piece. (It’s mostly about why New Year sucks, and outlines my prediction that 2024 would be the Year of the Tardigrade, but it also contains more generalised anti-holiday sentiment.)

That still wasn’t what I was thinking of, though. I then had the brainwave of searching Holiday, and found this one. Like it says on the tin, it’s mostly about orchids, but it includes an anti-holiday rant shoehorned in about halfway down: “Humour me for a minute. In my Utopia, everyone would be free to follow their vocation.”

However, awareness of seasonally appropriate festivals is slowly growing. Here in Wellington, for instance, Lōemis have facilitated many wonderful public Solstice celebrations, from burning giant effigies on Whairepo lagoon to all-night sleep concerts.

I tried not to walk along gazing at my phone like an idiot, but sometimes it was necessary. London is rife with phone-thieves on bikes who ride up behind people and snatch their phones out of their hands. Maddy said she witnessed one theft where the thief also kicked the victim over, just to add insult to injury.

As well as an open doorway, there was a side-window between the two, like a serving-hatch.

I made a pilgrimage on my Dad’s behalf to the grave of his favourite composer, Johann Christian Bach, in St Pancras churchyard, which was an amazing place. (Mary Wollstonecraft is also buried there, which makes it ((as someone reminded me later)) the place where Percy Bysshe Shelley deflowered young Mary Shelley. The story of Mary Shelley is an awful one, but if you can face it, I recommend Jeanette Winterson’s Frankissstein, a novel which includes Mary Shelley’s life story.)

Ephesus (Greek at the time, but in modern-day Turkey) was famed for the Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders, the largest building in the Ancient World. It was a city where even women could be artists.

Saint Paul came to Ephesus around 52 AD and became embroiled in a dispute with artisans whose livelihood depended upon selling statuettes of Artemis in the Temple. (Pagan! Idolatrous! Not OK by him!)

He also wrote the letter to the Corinthians there. So it's those aforementioned artisans he's talking about, I guess, when he says: "I protest by your rejoicing which I have in Christ Jesus our Lord, I die daily.

If after the manner of men I have fought with beasts at Ephesus, what advantageth it me, if the dead rise not? let us eat and drink; for to morrow we die."

à la Žižek

Instead they take Vitamin D supplements and use ‘sad lights’ to stave off depression

Apparently the mistletoe-kissing thing is mostly Dickens's fault- read all about mistletoe here: https://overthefield.substack.com/p/a-very-festive-parasite

I am increasingly disenchanted with the ridiculousness of Christmas , with religions in general and with the idea that a strange little man is planning to slide down a gazillion chimneys on December 24. But I too will sneak into churches to listen to choirs sing, and while (unlike my mother) I don’t have carols playing incessantly during the season, I do enjoy playing the Coventry Carol on my tenor saxophone…it makes utter magic of the melody.