Heather Christle, The Crying Book: “Writing a poem is not so very different from digging a hole. It is work. You try to learn what you can from other holes and the people who dug before you. The difficulty comes from people who do not dig or spend time in holes thinking that the holes ought not to be so wet, or dark, or full of worms. ‘Why is your hole not lined with light?’ Sir, it is a hole.”

I moved house a few months ago, after twelve years in the same place.1 The old house had become harder and harder to love. Its ramshackle bach-y charm had degenerated with the years until it tipped over into rotten old shitbox. Because conditions changed so incrementally, I adapted to them, until I didn’t.2 The walls became more porous. Life throve inside: moths, mice, mould. A mushroom grew upside-down out of the living-room ceiling. The concrete backyard, spring-fed by a leaking shed-toilet cistern, rewilded itself into a primordial swamp.

For the last few months of habitation, as tyre-kicking strangers3 trailed through in the wake of the pointy-shoed real estate agent, I laboured on a rage-fuelled essay about the housing crisis that grew more and more convoluted, never resolving into coherence. I dreamed repeatedly about water under the floorboards, water coming in through the walls and roof. (Unsound, unsafe.) It felt just like a relationship gone sour, because it was. I had once loved this house so deeply, and now I was ashamed of it, embarrassed that it had come to this, like a mouthful of decayed teeth. I could hear starlings rustling under the eaves and rats tumbling inside the walls, and I was like, Have at it.

The word rent is related to render: ‘Render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s.’ The Latin root, reddere, means to give back, return, restore. But rent is also a torn place, an opening made by rending or tearing, a kind of ripped-open wound. Even though relations between the house and me had been deteriorating for a long time, even though the situation was unsalvageable, still, leaving was like being uprooted.

My houseplants never flourished in the old house. It was oriented roughly East - West between two hills, with windows along its flanks which were shaded for most of the year. Shade made it cold, especially in Winter, and permanently semi-gloomy. Plants eat heat and light. Sometimes one plant or another would put on a burst of growth, a Summer flowering, but mostly they were sluggish, half-hibernating.

Hardier plants did better. The succulents were left to their own devices on the back step. The Christmas cactus— which I’d taken on by repotting it from its tiny hanging pot in the kitchen window— went bananas, grew into a fat-trunked triffid, and popped out an annual cascade of hot-pink frilly blossoms that leaked sticky nectar onto the windowsill. The hoya, which I’d had for a decade, grew occasional vine-tentacles, and mostly flowered while I was away over the Summer holidays, its peduncles pushing out stalked buds that became hemispheres of furred stars, perfuming the night with moth-pheromones.

But the rhipsalis cutting a friend gave me grew at a glacial pace, then stopped. The ladder ferns in the toilet (which I had also somehow inherited custody of) got scale, which spread to the philodendron;4 then when I threw the fern out, the coffee plant someone put in the same cursed toilet spot got mealybugs. Certain types of plant— anything tropical or delicate, moth orchids, pitcher plants— I didn’t even attempt; the prevalent conditions would have meant a slow death.5

When I moved, to a little cottage up the hill with skylights, big windows, and a heat pump, the plants came alive, even though it was the middle of Winter. At the old house we used to call our small backyard greenhouse Fiji.6 My plants quickly thawed, awoke, and found themselves, if not in the tropics, then maybe somewhere more like Northland, where a stick poked in the ground grows, and the bush swallows abandoned houses. Responding to the new climate, they immediately began to put on growth, unfurling new leaves to the light’s bounty, tilting them like sails for optimum catchment.

As time passed in the old house and my flatmates got younger, I noticed that they were far less cold-tolerant than we had been.7 The coldness of houses seemed, for my generation, an unalterable condition of being: one that we adapted to by putting on more clothes, huddling over heaters, and just basically being cold a lot of the time.8 My internal response to the softness of the youth was a weird mix of anger and judgement: Well, WE had to put up with it. Harden up. Put a jumper on.9

Why should I wish suffering on others? Was it just a kind of retrospective self-gaslighting? When I dug further, it seemed to have something to do with the fact that to me, substandard housing was an unalterable condition of life. To them, flatting was but a train station on life’s railway, whereas for myself, I could see a potential future trajectory where this way of life continued forever. The Devil’s bargain, the trap’s bait, was the cheap rent that made my creative work possible.10 When my friend’s Dad— an amazing artist— died, he was living in a single bedroom of a nondescript flat in the Auckland suburbs. His life’s work was in that room, in boxes; a half-inked page sat on the drawing board. It was unheimlich, my vision manifest.

When we put a plant in a pot, we become God to it. Its roots are bounded by the edge we decide. Its sustenance comes at our pleasure. The house is also a kind of container. When we rent a house, we have little power over what we can do to it.11 Renting is largely a matter of attempting to keep things the same, of limiting damage to the vessel, which after all, we don’t own— we just buy the temporary use of. The will to enact meaningful change in our surroundings is thwarted by the naked fact that the shelter over our heads exists only at someone else’s pleasure.12 In this way the natural human desire for improvement of one’s immediate situation, for beautifying and experimenting, is nipped in the bud.

The term for this hopeless, passive state— when it arises as a result of trauma— is learned helplessness. The stork dropping babies is not a bad metaphor for how a child falls into a random family not of its choosing.13 A baby is a seed dropped on fertile soil or stony ground, which then has to try to grow. I sometimes use the Dao-influenced metaphor of the crooked tree to explain childhood trauma. The sapling seeks light, twisting itself around whatever immovable obstacles block its way. Then people look at the bent and twisted adult tree and say, Why are you so crooked?14

The point is that green life seeks growth by whatever available means.

Kev got two free pumpkins— butternut squash— from the Tokomaru Country Club, where someone was giving them away for free. (A glut.) After we ate the first one,15 he salvaged the seeds, washed them, dried them on a plate, and counted them: 225.

This is Nature’s way. Inside a fat orange belly, an ejaculation; enough seeds to start a pumpkin farm.

Another reason my plants weren’t thriving in the old house was that I didn’t understand soil composition. (‘Potting Mix’ must be for potting things, right?) I was so loath to disturb their delicate life-thread that once repotted, I tended to leave them alone.

In my new house, with my plant-horizons expanding, I started to research more deeply into what each one needed. I’d felt guilty about the hoya’s yellowing leaves, and consulted the green elves of Turtle Therapy, who sold me a paper bag of special hoya mix, but told me to wait until Spring to repot. The ingredients were written on the bag in pencil: Bark, pumice, fern fibre, worm castings, LECA, coco coir, dolomite, biochar. I didn’t know what half of those things were, but it was a great relief to outsource the cooking to a trained chef.

The hoya is my oldest plant-friend, and lives in my bedroom. Sometimes it communicates with me in dreams: I’ll dream I’m watering it, for instance.16 A few nights ago, after I repotted it,17 I dreamed I was putting more soil in around the edges. The next day I obeyed the request, spooning more soil in carefully around the edges of its stems, like tucking a blanket around a baby.

Each individual plant needs what it needs. Each plant comes from a specific environment, and we must try to mimic the conditions of that home-ecosystem as best we can. The staghorn fern18 I bought yesterday from Bunnings Petone— an epiphyte— likes to be tied to a piece of wood and hung on the wall. We don’t shame the plant for needing what it needs: it’s just science. If we don’t give it what it needs, it won’t grow. If it isn’t fed, if it doesn’t feel safe, it won’t flower. Plant-science is a pleasure— plants are living beings, and they respond to care eloquently, by being happy; by growing.

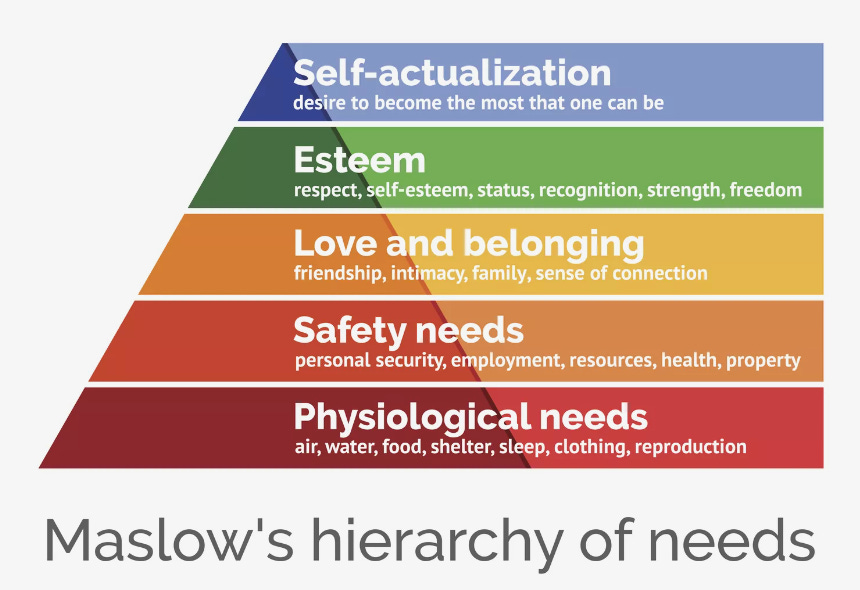

For humans, the needs of life are partially personal and partially universal.19 The individual needs can only be understood by trial and error.20 We are bespoke creatures: other people’s accumulated knowledge can guide us, but ultimately we are Captain of our own ship. The universal needs are often described with reference to the work of American psychologist Abraham Maslow. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is usually conceptualised in the shape of a pyramid, although this was not a form applied by Maslow himself:

The most basic level, the wide base of the pyramid, concerns physiological needs, the primal conditions for human survival: air, food and water, shelter, warmth, health, hygiene, and sleep. (When needs for air, food, or water are not met, a person will quickly die. Warmth, shelter, hygiene, and sleep are the needs that housing meets: when these housing needs are not met, we call a person homeless. The homeless person’s life expectancy drops dramatically.)

Let’s climb: we move up the pyramid from Physiological Needs through Safety and Security (protection from violence and theft, emotional stability and well-being, health security, and financial security- also needs that are intertwined with living situation); Love and Belonging; and Esteem, both self-esteem and the esteem of others. These four basic levels are considered ‘deficiency needs’: that is, if they are unmet, the human cannot function well.

Only when we come to the top of the pyramid— the capstone— do we reach Self-Actualisation needs, which are considered ‘growth needs’. (That is, they are to do with the fulfilment of an individual’s highest potential.) The list of ‘meta-needs’ that falls under the heading of Self-Actualisation includes such lofty, lovely ideals as Wholeness, Perfection, Justice, Complexity, Beauty, Playfulness, Truth, Meaning.21

Metapathology is Maslow’s term for the thwarting of self-development that results from failure to satisfy the meta-needs. Metapathology prevents potential self-actualisers from self-actualisation, from engaging with their latent genius.

Poor artists, then, practicing in precarity, are balanced on the top of the pyramid, leaning out to catch flitting meta-needs in a net of twigs and string, while far away below the base layer crumbles away like soggy weetbix. Is ‘the need to self-actualise’ another name for the intrinsically-motivated drive that makes artists vulnerable to exploitation? (I will continue to make, come hell or high water, or my life is not worth living. I will do good work for my own honour, regardless of how little you pay me. I will choose to act in service of my craft, and take the personal hits that result.)

Maybe those who continue along the road of art are simply those in whom the drive to self-actualise is stronger than the need for self-preservation.

For a plant to grow, to flower, it needs the right conditions. It doesn’t feel ashamed if those conditions aren’t met: it just ceases to put its energy into growth. We humans are no different. It’s interesting to apply the metric of ‘needs’ to the conditions of creative life. It makes it all seem less willed, less personal; it alleviates shame. Bread and Roses, when we break it down,22 means not only that art is as necessary to the human spirit as food is, but that art is the outcome of being adequately fed (and warm, and safe), just as a plant’s flowers are.

For the first few weeks in the new house I waited for a name to arise. I was used to living with multiple others; the name of my old house was The Happy Valley Free Multiverse. Suddenly I was alone. I had uprooted and repotted myself. I watched the moon move across the skylights, dawn’s light move down the hillside. This new house was inhabited by the plants, the spiders,23 and me. I found myself the token vertebrate. The spiders went about their spider-business— I admired them, but they didn’t pay me much mind. I inhaled oxygen, breathed out carbon dioxide; the plants inhaled carbon dioxide and exhaled oxygen.

More than one visitor said that being in the house felt like being on a boat. To me, it felt like living in a bubble. Solitude made me newly conscious of the edges of my personal ecosystem. The lack of external structure24 made me more conscious of my natural rhythms. After a while I realised that the condensation I vacuumed off the windows could be fed to the plants— distilled, free of tap-water’s chlorine.25

The house’s name arose, condensed out of the air like water: The Terrarium.26 It’s a dwelling like a suit of clothes; elegant in its minimalism, sufficient to sustain my life. Within its walls, I am the prime mover, the agent of change; I add things— food, supplies; remove things— rubbish, waste; move things around; improvise combinations of matter and thought.

James says that the act of gardening reminds us that dying is OK.

Amelia, sixteen months old, child and Grandchild of serious gardeners, strews handfuls of oats onto the floor. Me: “Sowing seeds is the age-appropriate garden task.”

Up in the top garden, with its vantage to the snow-covered mountains, I sprinkle parsley and dill seeds. Despite the snow, Spring is nearly here.

The same room of the same house, even.

Shifting Baseline Syndrome. Then— just like a break-up— when the end is nigh and you let go of clinging on, the true shitness of the situation hits home.

The violated feeling it gave me when these randoms looked into my bedroom seemed familiar. It took a while to pin it down: it felt just like the time the police illegally searched me (during Operation Eight.) The feeling is, not only do you have to let this complete stranger examine your personal space and possessions, but you have to pretend to be OK about it. At least— unlike cops— potential buyers are not allowed to touch your stuff, open drawers, etc.

I had to spray it with soap and oil.

Grim Reaper: “I’m here for your houseplants.”

Cobbled together from scrap wood and plastic

Europeans fresh off the boat express horror at the shoddiness of the houses here. My friend Dan points out how people in New Zealand say, The house is uninsulated and freezing because it’s old. As if that makes logical sense.

“But I’ve lived in houses from the 1700s, in England. They’ve been constantly upgraded! They have central heating installed!”

At least Wellington isn’t Dunedin. I remember visiting a Christchurch flat where a ring of boys stood around the hot knives slotted into the element, while snowflakes blew into the open door.

Never did me any harm! Obviously, this response— just as when people invoke it to defend childhood beatings— is a form of psychic self-defence, driven by the need not to have one’s own coping strategies undermined.

One way gentrification plays out: choices diminish. No longer could renters choose where to live— increasingly, they had to hunt and grovel and eagerly pay whatever outrageous sums were demanded.

And to a certain extent, in it.

The literal meaning of precarity, which is related to prayer: at the will or pleasure of another.

Don’t give me that woo-woo shit about people choosing their circumstances.

“Why is your hole not lined with light?’ Sir, it is a hole.”

Which took three days’ worth of meals—

When I was in Auckland, sleeping in James’ room, the Dendrobium kingianum I’d bought as a gift some years ago talked to me in a dream: I dreamed a person was mixing up a careful combination of bark and moss, this and that, to repot it. When I woke up I told James, “I think the orchid wants repotting.”

”I just did that,” said James. “It’s only just recovering from the trauma.”

”Huh! Maybe it was telling me what happened, then.”

Like a farmer timing lambing too early, I didn’t foresee the snow-snap of the last few days.

As the meme goes, Drink water. Get sunlight. You’re basically a houseplant with more complicated emotions.

What happens if I try this? Ah yes, abject failure and humiliation. What happens if I try it again? Hmmm, the same outcome. How about now? etc. etc.

Compost and breadcrumbs

So many kinds of spiders! My (mildly arachnophobic) landlady’s name for it: The House of Spiders.

No flatmates waking, sleeping, eating— no group-rhythm of the household. No intermingling of possessions, no rough and tumble: I brought my collection of beautiful, delicate glass cups out and started to drink from them.

Brought up drinking rainwater, I still sometimes notice the smell or taste of city water, though I’m mostly used to it now.

Strictly speaking, Vivarium is more correct— there are animals (me and the spiders); but I like the way Terrarium suggests a self-sustained ecosystem, a garden in a bottle.

I found this quote by Thoreau, from On Civil Disobedience: “If a plant cannot live according to its nature, it dies; and so a man.”

I hunted out the quote in full: "I perceive that, when an acorn and a chestnut fall side by side, the one does not remain inert to make way for the other, but both obey their own laws, and spring and grow and flourish as best they can, till one, perchance, overshadows and destroys the other. If a plant cannot live according to its nature, it dies; and so a man."

Oh my goodness I loved this piece so much! "Maybe those who continue along the road of art are simply those in whom the drive to self-actualise is stronger than the need for self-preservation" - your writing and thinking has already alleviated some shame here, thank you.