Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed: “We are sharers, not owners. We are not prosperous. None of us is rich. None of us is powerful. If it is Anarres you want, if it is the future you seek, then I tell you that you must come to it with empty hands. You must come to it alone, and naked, as the child comes into the world, into his future, without any past, without any property, wholly dependent on other people for his life. You cannot take what you have not given, and you must give yourself. You cannot buy the Revolution. You cannot make the Revolution. You can only be the Revolution. It is in your spirit, or it is nowhere.”

I was walking the wrack-line a few days back when I saw a prickly sphere in the driftwood. Kina, went my brain— sea urchin; a brief mental struggle,1 then— wait, no… Hedgehog. A dead hedgehog’s round back, radiating spikes.

Later that night, I was reading my book (The Golden Mole by Katherine Rundell), and found this: “Although hedgehogs are ancient— they existed almost unchanged fifteen million years ago, back when we were still great apes— the name hedgehog is a recent invention. In Middle English they were irchouns— from the Latin ericius, a spiky military rod used for defence— or urchins… The sea urchin, then, takes its name direct from the hedgehog.”

I thought, then, about the other meaning of the word urchin: a street-child, like the Artful Dodger. (Is the link the thistly hair? Tufty, spiky— unkempt / uncared-for kid?) Etymonline says: “Applied throughout 16c. to people whose appearance or behaviour suggested hedgehogs, from hunchbacks (1520s) to goblins (1580s) to bad girls (1530s); meaning ‘poorly or raggedly clothed youngster’ emerged 1550s, but was not in frequent use until after c. 1780.”2

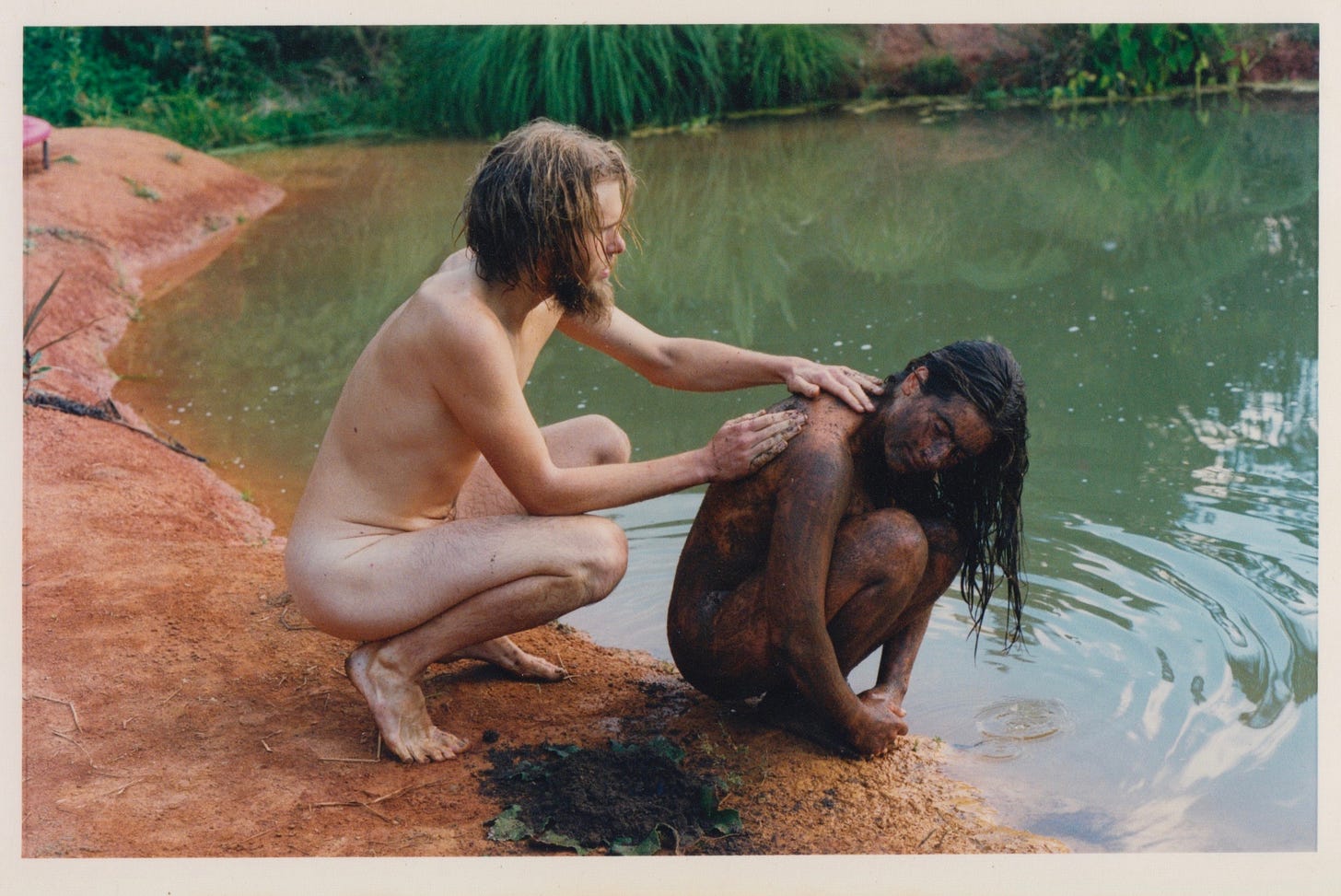

The next morning, I gazed out the bus window at the window-washer, as he strode through the traffic paused by the red light. (I was invisible to him, outside his sphere of attention: the bus window wasn’t one he could wash.) He wore a blue denim vest over a black leather jacket and skinny jeans— which made him kind of lollipop-shaped— and a black cap, and he swung his squeegee like a baton as he walked, conducting a lively conversation with drivers using only his body: Window-wash? No? All good, sweet as. The energy of his movement, his aliveness in that moment, made me happy, made me think good for you, you’re still unbowed, they haven’t ground you down.

He reminds me of a West Aucklander, he looks like boys I went to school with. Something about the cast of his face— thin, with scraggly facial hair; a wiry, engine-oil, hard-knocks vibe. His patch is at the junction of the Bypass, Willis, and Abel Smith Streets. Energetically, that corner is like a bank in the fork of two big rivers, because both the Bypass and Willis Street are one-way, flowing ever downwards. There’s protection from the elements, too, in the form of an open-sided crossing shelter, just a roof on top of a single wall. Oftentimes there are other crust-punk-type people there with him on the corner, sometimes a dog or two. But here he was, bright and early, to work the morning traffic, alone.

I got off the bus and walked up towards Aro Park thinking about money, thinking about how the application of money is the main way to move things around in a world where almost everything costs. (Those flowering plants there, for instance, in the garden bordering the path, they didn’t come for free. They cost someone money to buy, and time to plant and upkeep, time that costs money.) Implementing change— making ideas real— becomes exponentially easier the more money one has. (It’s to do with lightness of choice, too, the freedom to act: making mistakes matters less when you have more.) I was thinking about the way way wealth reinforces itself; but not just that, the way it spills over at the edges, the abundance and ease of having more than enough that I see in my fellow denizens of this prosperous city, the Boomers and bureaucrats,3 with their clothes and shoes and houses and cars and holidays and restaurant meals and jewellery.

I was thinking too, that what I have, they lack— the ability to conjure something from nothing; but also that what I have— my craft, the fruit of my labour— is routinely devalued. (Literally devalued, as art can’t be quantified: it’s non-fungible.4 If a thing can’t be priced, does it have value?) Walking under the bursting green trees of Aro Park I was thinking with a kind of awe about how people keep going in the face of opposition and fatigue and poverty; artists and makers, that is, how they keep on drawing from the well, driven by powerful internal compulsions.5

As I came up Aro Street, the window-washer came strolling down the pavement towards me with a six-pack of beer in his hand, blue cans from the dairy, and I smiled at him, and he said “Do you want a beer?”

”No thanks, I’m good,” I said.

(It was the first human exchange I’d had that day. Auspicious!)

We crossed paths, and a few seconds later the morning flooded into my veins in a rush— joy, Spring, expansiveness, pollen, luck, light.

I have had so many other experiences of this kind of altruistic stranger-generosity. There was the time a homeless person, seeing me looking in the gutter (a finder’s habit) offered me a cigarette, thinking I was hunting for butts. (The window-washer, seeing me looking at his beers, had read my curiosity as a thirst for beer.) When I haven’t been able to afford food, friends have fed me.6 At least once a week— more usually twice or three times— I see someone’s Snapper card decline, and the bus driver wave them on for free.7 In my years of hitch-hiking, the people who picked me up often said— more often than not— that they had been hitch-hikers themselves, they knew what it was like to be the one with their thumb out. (Flip-side: when I’ve had a car, I’ve picked up hitch-hikers.) The generosity of the poor and disenfranchised is both a true thing and a moving thing. It’s the karmic open-handedness of those who have little, and therefore know what it is to need help.

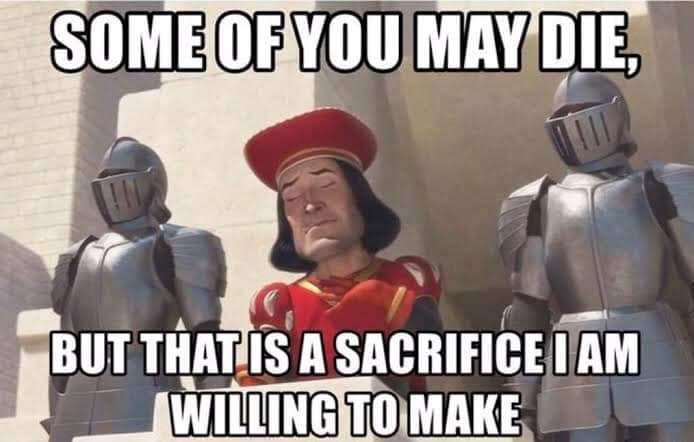

The opposite of this spirit of mutuality is someone like multi-millionaire Christopher Luxon,8 walled up in his palaces of gold, insulated from lived understanding of hunger, or struggle, ignorant of the terrible beautiful riches of the spirit that can’t be extinguished in the human being,9 like dandelions flowering in a bomb crater, confetti-ing their airy seeds to the wind. Luxon— with his legions of minders trying to make sure he doesn’t do or say anything too dumb— pulling out the tired old beneficiary-bashing dog whistle, a logical progression from his comments last year: “And if you want to have a go and you want to make something of yourself, we don't just do bottom feeding and just focus on the bottom, we focus on people who want to be positive and ambitious and aspirational and confident, right?”

This is what passes for virtue-signalling, on the right, in election season. However, as Josh Drummond points out in his latest Bad News Letter, “New Zealand pioneered the art of making inflation (when everything becomes more expensive) go away by raising interest rates (which makes everything more expensive), and intentionally creating recessions and making people unemployed to fix the economy.

I fear that last bit might have escaped attention due to how mind-boggling it is, so it bears repeating: unemployment is intentional.10 Our low wage economy is kept that way, on purpose, lest we awaken the inflation boogeyman… Somehow, it’s still not common knowledge that the economy is set up to make sure that around five percent of the population will not have jobs.”

Lewis Hyde says in his seminal book on creativity and the gift economy, The Gift: “It is the cardinal difference between gift and commodity exchange that a gift establishes a feeling-bond between two people, while the sale of a commodity leaves no necessary connection… To take the simplest of examples, the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss tells of a seemingly trivial ceremony he has often seen accompany a meal in cheap restaurants in the South of France. The patrons sit at a long, communal table, and each finds before his plate a modest bottle of wine. Before the meal begins, a man will pour his wine not into his own glass but into his neighbor’s. And his neighbor will return the gesture, filling the first man’s empty glass. In an economic sense nothing has happened. No one has any more wine than he did to begin with. But society has appeared where there was none before.”

An example of gift exchange: whenever I have cause to engage with the public health system, I have an emotional response. It happens almost every time. In the hospital, the nurses and Doctors and orderlies are paid, of course, but as a patient, one receives care for free, and the feeling this usually gives me is one of deep gratitude and even love towards these knowledgeable strangers who are so kind to my body. The healthcare feels like a gift because it’s free of charge; that’s the wellspring, the source of this reciprocal warmth. This gift of care feels big; it makes me want to give something back. I try to remember to express my appreciation in words, light to carry, freely given.

Here we are in Polynesia. It is understood here that (in Hyde’s phrase) the Big Man or Big Woman is not the one who grasps and accumulates, who hoards, but the one who expedites, who gives; the person who is a living river the abundance moves through, a force for good in their community. The community and the individual are not separate. The person is not solo, not walled-off; rather they are a drop of water in a body of water, working for all, mo te iwi.

This open-handed, communal way of thinking is so alien to commodity-thinking— to those who live their lives in a world of pure cost-benefit analyses— as to be literally invisible.11 (How can the privileged observe exchanges of energy that have no value whatsoever in their system?) Think of it this way: the spirit of the gift is a candle flame. Others can light their wicks from yours, then there is more light. (The law of the gift is that it must not be held or hoarded; it must keep moving, or it ceases to be a gift.) Those who live their life by electricity are so dazzled by fluorescent glare that they say— what candle light? Nevertheless the gift economy is absolutely real— the fire is warm, and old, and uncontrollable. The world runs on its energy, it underwrites Capitalism;12 and it is far more ancient and deeply human than any price-stickering of life. In virtually all hunter-gatherer societies (ie., the way human societies ran for most of human prehistory) the prohibition on selfishness is absolutely central, and transgressors are harshly punished.13 When sharing is survival, selfishness is death.

Following this ancient logic, the act of hoarding millions of dollars is an indictment, clear evidence of anti-social pathology. Le Guin’s Anarchist philosopher Odo says in The Dispossessed: “Excess is excrement… Excrement retained in the body is a poison.” In the Anarresti society built on Odo’s philosophy, the most contemptuous name you can call someone is profiteer.

I’m not trying to glorify poverty and damn wealth. I’m damning those people who— having so much— seek to shame and punish those who lack, unable even to see that it’s themselves they shame. And I’m trying to name the reaching-out that happens among those who understand that there but for the Grace etc., go they. These are not hard-and-fast class rules; rather, they are distinctions of character. I’m talking about the power of the gift to make rich, to make even the poorest into The One Who Gives.

It strikes me that those who primarily self-identify as sovereign individual-as-consumer, denying community and society,14 seem to believe that the dividing line between have and have-not is a solid wall, metres high and topped with broken glass, patrolled by sentries. I tend to think of it as more like a boundary between neighbouring countries, maybe sleepy European ones: a purely theoretical line that can be stepped back and forth over. (OK, maybe it’s on a mountainside, so that going downhill is easier than climbing back up again. It’s easy to slip, to fall, to wake up and find yourself broken over the rocks; nobody is immune to bad luck.)15 It makes me think of the Susan Sontag quote about every human being holding dual passports to the kingdom of the well and the kingdom of the sick.16 (What if— some distant future day— your visa to the Kingdom of the Rich is denied, and the guard won’t let you in the gate?)

The periodic kicking-down at those below performed by certain politicians at election time seems to me a kind of performative ritual to reinforce their Neoliberal-separatist religion. (The proof of it being ideological rather than scientific is the fact that punishing the poor doesn’t really work: obviously, harsher sanctions will not make desperate people more servile. The need to feed children, or an addiction, will make them rob your fancy house.) This ideological fixity is an attempt to shore up the belief that they somehow deserve the wealth they hoard— that others are just more lazy, more feckless, less deserving, inferior. Ultimately, though, faith in the market is only as good as the promises of the market. Money is a matter of belief: the value of a dollar, the value of an asset or a business— these are not fixed, they are as fluctuating as weather. The very-rich are compelled to constantly solidify and reinforce their wealth because on some level they understand that what they are clinging to is a liquid thing.

Ironically, understanding value and worth in purely economic terms is the real poverty; it renders so much of human experience invisible. Human beings are apes, communal to the core. The very fact that you are alive today is proof of the cooperation of millions of ancestors. No amount of money can fill the psychic black hole where faith-in-other-humans and solidarity should be.

I pick up Rundell’s hedgehog-essay again. “In 2015 the Tory MP Rory Stewart gave an impassioned thirteen-minute speech to a largely empty House of Commons, entirely about hedgehogs. It was the first time the hedgehog had been discussed by parliament, he said, since 1566.”

Stewart is an interesting dude— a leopard who changed his spots, leaving politics, writing a tell-all memoir about his decade as a Conservative Cabinet Minister; starting a smash-hit bipartisan podcast, The Rest is Politics; and getting a job with an NGO that advocates unconditional global redistribution of wealth. Where there’s life there’s hope!

Less than a week out from election time, a meme’s been doing the rounds of my friends. Red and pink hand-script on a sea-green ground: THINK OF THE MOST VULNERABLE PERSON YOU KNOW AND VOTE IN THEIR BEST INTERESTS. (Bear in mind that you could easily become that person: age, accident, disaster. Bear in mind that the actual most vulnerable people in our society are the children of the most vulnerable adults; who didn’t choose to be born.)

Please vote, if you haven’t already, and please don’t vote for dead-eyed bastards. I was trying to think of a voting metric analogous to the ‘Two beers and a puppy’ theory; but Government is not like friendship. Vote, then, for someone you’d be happy to have as a landlord; someone you’d be relieved to see on the judges bench if you’d been wrongfully accused; someone you’d be keen to have as a collaborator on a big project.

I met a poet named Joan last night who told me that when she’s Queen (or King, she said), Members of Parliament, as part of their term of office, will work a low-status job— care-taking, retail, fast food— for six months. (Who would you vote for, if you knew they’d be looking after your Grandma?)

A century and a half ago, women weren’t allowed to vote; our ancestors fought to give us that right. Yesterday while I was sitting at the bus stop, a Somali woman with small English asked me the way to the polling booth. Election time often moves me in the same way that going to the hospital does. Fellow-citizens running the polling stations, helping each other; and the fact that when all’s said and done, it comes down to humble felt-pen and paper inside a cardboard booth. Such a small thing, an ordinary thing, making marks with my hand.

Vote, my friends, vote for the least-worst option if you have to! Give your countryfolk that tiny democratic gift. And talk: tell the fools who are all ‘Voting doesn’t make any difference, all politicians are the same,’ to kindly shut up, encourage everyone you know to vote, help them if they need help to talk it over, go with them to the polling station. Voting is an act of civic faith. Your little drop of the ocean helps to make a wave— every vote matters.

My brain really wanted it to be a sea animal.

What was happening in 1780? The American Revolutionary War was still in full bloody swing: five years in and three to go. In June 1780, the anti-Catholic Gordon riots in London led to the killing and wounding of hundreds of rioters by the military. (Some historians consider this to be a close-call English revolutionary moment.) In November 1780, in Peru, the peasants revolted in the Rebellion of Túpac Amaru II— an attempt by indigenous Peruvians to overthrow Spanish colonial rule. (Tupac Amaru Shakur, the child of Black Panther Party activists, was named for him.) The late 1700s would be a revolutionary time.

In Aotearoa, it was a decade since the arrival of James Cook, in 1769.

Broadly, the Enlightenment was turning into the Industrial Revolution. (1779 was the year of Ned Ludd’s apocryphal frame-smashing.) In Britain, the Inclosure Act of 1773 had further restricted access to the Commons, and thus to the means of survival. Working people could no longer provide for their families (as the folk songs of the time tell); the root cause of the proliferation of urchins / hungry children on the street.

#notallBoomers #notallbureaucrats. Specifically, having had more than enough for so long— maybe always— that one can’t remember or understand not having enough.

Fungibility, in economics, is the quality of being interchangeable. For instance, you can swap one sack of grain for another; but you can’t swap the Mona Lisa for anything equivalent, because it’s a stand-alone masterpiece.

My ideas around creative motivation have changed of late. I now think of it as a survival tactic.

Food: the most fundamental gift of all, the gift of continued life.

When the Snapper machine is out of order, the bus drivers seem stoked about it as they tell everyone, it isn’t working, just get on!

Note for non-New Zealanders: a right-wing happy-clappy politician fairly likely to become our next Prime Minister.

This sentence sparked memory, and after a bit of thought I realised I was half-quoting Le Guin again, from The Left Hand of Darkness: “It is a terrible thing, this kindness that human beings do not lose. Terrible, because when we are finally naked in the dark and cold, it is all we have. We who are so rich, so full of strength, we end up with that small change. We have nothing else to give.”

My emphasis

The ultra-rich, in their insulation from adverse consequences, are also removed from the interpersonal feedback loop that keeps normal people from getting too far up their own arses. This can be seen at its most extreme in billionaires like Musk, Bezos, or Trump, who— entirely surrounded by a narcissistic mirror of Yes-men— genuinely can’t see how stupid they look.

There are many, many examples of altruistic, unpaid daily labour: work within the family— parenting, care of elders— is an obvious one.

This is also why it’s totally ridiculous to retro-fit the nuclear family paradigm onto our Stone Age ancestors: don’t get me started.

Margaret Thatcher, infamously: “There is no such thing [as society]! There are individual men and women and there are families.”

Emily Writes recently posted a guest piece on one family’s downward slide due to the premature death of one of the parents, by Helen Gilby: I'm the Deserving Poor, and You Could Easily Become Me

Sontag: “Illness is the night side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.”

After reading a particularly sobering essay this morning that left me heartbroken your words here put it back together. Thank you

I live in the USA, and folks like me living here can't really get all excited about our "right" to vote. But I'm glad the author of this piece feels that she lives where her vote matters and is precious.

I love the kindness, compassion and generosity in this lovely little essay.