Skull-Box / Page-Box: On Memory-Palaces

Does the mind have a structure? When written words come alive, who speaks back? How are songs like gold coins?

Henry David Thoreau, journal entry, August 19th 1851: “The poet must be continually watching the moods of his mind, as the astronomer watches the aspects of the heavens. What might we not expect from a long life faithfully spent in this wise? The humblest observer would see some stars shoot. A faithful description as by a disinterested person of the thoughts which visited a certain mind in threescore years and ten... As travellers go round the world and report natural objects and phenomena, so faithfully let another stay at home and report the phenomena of his own life,—catalogue stars, those thoughts whose orbits are as rarely calculated as comets. It matters not whether they visit my mind or yours,—whether the meteor falls in my field or in yours,—only that it come from heaven… A meteorological journal of the mind. You shall observe what occurs in your latitude, I in mine.”

My brain resides full-time inside my skull, but my mind is far less tidy. My wandering mind has dens aplenty outside of the bone-house. When I began to seriously WRITE, by which I mean write for people other than myself to read, I understood that I write to create an external brain. Writing is using language to make a space where I can lay out some of my mind and examine it, shape it, re-form it.

I’ve been journalling full-time since my early 20s, and I know from experience that when I don’t write in my journal, I become crazier and dumber. Writing for myself is a private exploration. Like a still, it clarifies myself to myself.1 Writing for others is more like getting the disparate parts of my mind in harness and ploughing the field of the page thoroughly, so that I can be understood. They’re different, but both are ways of seeking self-knowledge through labour; seeking to clarify my thinking by taking it out of the skull-box and putting it in the page-box.

As a writer, the most exciting kind of writing is the kind that comes alive and speaks back, that tells me something I didn’t already know. It’s a feeling of exploration, discovery, magic. (Who or what are you in dialogue with when that happens? In the old days they called that force the Muse, which is also a word for a flavour of thought— pondering, daydreaming.) This is writing as digging, or writing as fishing, as in Virginia Woolf’s famous metaphor that I found via Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1988 essay, The Fisherwoman’s Daughter. (Le Guin quotes from an early draft of Professions for Women, the speech Woolf gave in 1931 to a female audience.)2

Here is Woolf’s female writer: “I figure her really in an attitude of contemplation, like a fisherwoman, sitting on the bank of a lake with her fishing rod held over its water. Yes that is how I see her. She was not thinking; she was not reasoning; she was not constructing a plot; she was letting her imagination down into the depths of her consciousness while she sat above holding on by a thin but quite necessary thread of reason.”3

Another thing that happened when I started seriously writing was that I noticed this weird little phenomenon. I’d be editing something I’d written months or years before then set aside— it’d be something I hadn’t looked at for a long time— I’d read a sentence, and a seemingly new idea would arise in response: Now, X or Y. When I went to add it, I’d discover I’d already written it— the next sentence would be exactly X or Y. That’s when I started to think about Memory Palaces, because it felt like my mind had an actual structure. It was like I was wandering back into a room where things lay just as I’d left them.

This is what I wrote about it, at the time:

“I’m noticing, now that I’ve been re-writing, the self-similarity of my thoughts, the orderliness. I’ll be reviewing a sentence and it will come to me what to say next, the next idea presenting itself for duty; then I’ll read on a few more words and see that I already wrote that very thing last time. It’s a kind of internal cohesion based on memory and structure, that gives me the feeling that the inside of my mind is a landscape full of buildings, that these buildings of thought still stand when I’m not looking at them, that I can go away and come back and they will have changed their decor maybe but the bones will be the same. This is like what is called a Memory Palace, or Borges’ infinite library, or the House in Piranesi:4 those are attempts to make a metaphor to describe this feeling of wandering in the landscape of one’s own mind, one's own internal invisible architecture. (I used to think of my memory as a war-torn landscape, with bombed places, shell-craters, shallow graves; places to be skirted, avoided, not thought about. But maybe it’s been long enough now— distance makes clean— that the bones are bare, that the creeping weeds have softened the broken edges of the bomb-holes.)

If there is such an internal landscape, if it has manifest reality beyond the metaphors we use to try to describe it, and if that’s the well we draw from when writing, then that is the thing in art which is impossible to duplicate: another person can never access it, the source— it is entirely personal, not only because it is formed by discernment and taste and habit, but because it borders on the vast oceans of the subconscious, drinks from its underground aquifers, and that is a territory that cannot be controlled or known.

This landscape, the shape of the invisible mind, is naked because it is organic as well as willed. Scooting along by the sea, fresh from my eclipse dream of the three big dogs, I thought that the subconscious is so present, so foundational, in the mindscape that maybe [the shape of the mind] is a city on an island, like in the lakes of Meso-America, or no, maybe it is a giant boat, floating on a deep ocean, like in Earthsea, the raft-people out beyond the edge of any islands.5

I can only speak of my own mind. It has become what Csikszentmihalyi in Flow calls ‘autotelic’: self-amusing. There are ways, he says, to inculcate autotelic selves in children, including freedom of choice, clear boundaries, respect for them as they are now, not as you would wish them to be, and so on. But it is also possible to build these qualities as an adult, by immersing oneself in the kind of activities that stimulate flow-states. This is the closest I’ve come to a theory that explains myself to myself, that feels sound.”

I started asking other people whether their minds had a shape.

Mum: “Young people’s memory is like a supermarket, brightly lit, with everything on display, but when you get old it’s a dusty archive, like a musty old second-hand bookshop, with ladders and stacks; and you’re like, I know I left that somewhere, now where is it?”

Me: “So, Kev, when you think of your mind, is there a shape, I mean, does it have a structure?”

Kev: “Yeah, like a murky pool I have to fish around in.”

(He made clawing motions in the air, as if sifting through mud with his fingers.)

Ruby was the only person who immediately understood what I meant when I started talking about the memory palace. “Oh, I call that the room. You know— the room inside here.” She tapped her forehead with her finger, just as I’d been tapping my skull with mine for days, to demonstrate what I meant: knocking on the brain’s front door. Inside the room, she told me, you can place things, you can move things around. “I used to assume it was a thing everyone had. I’d say you know, the room; but they wouldn’t know what I was talking about.”

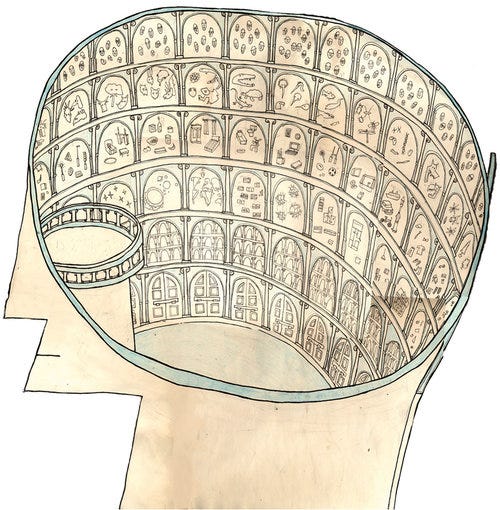

Strictly speaking, Memory Palace means something different to the way I’m using it here. It’s more commonly understood as a mnemonic technique, also called the Method of Loci: a way of remembering complex information by creating an imaginary structure in one’s mind and placing encoded information within it. (The information can be retrieved by moving through the imaginary space.) I’d read about it in a Renaissance setting— Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell uses it, in Wolf Hall6— but the Memory Palace technique originates in Ancient Greece.7 The origin myth tells of Simonides of Ceos, who had stepped outside of a banqueting hall when it collapsed, killing everyone inside. By reconstructing the room in his mind, Simonides was able to say who was sitting where and thus identify the dead.

As I read further into the book I bought in Pegasus last week— a strange book, in unedited idiosyncratic English: To Have and to Hold; An Intimate History of Collectors and Collecting, by Philipp Blom— I came to a chapter titled A Theatre of Memories, which opens with a description in a 1532 letter (from Viglius Zuichemus to Erasmus of Rotterdam) of Giulio Camillo’s Theatre of Memory: a wooden structure designed to systematise all human knowledge.

Blom on the Theatre of Memory: ”The historian Francis Yates has attempted to reconstruct the interior of this building… The panorama presented to [the viewer] was a seven-tier amphitheatre divided into seven segments, each fronted by one of the seven pillars of wisdom that were supposed to have stood in Solomon’s temple. The galleries… [were peopled by] symbols, trapdoors and inscriptions, all of which formed a metaphorical order of the world…

The star of this theatre was the human mind, or more precisely, memory. The structure was nothing more than a mnemonic system, allowing him to visualise everything on earth and put it into its appropriate place in the symbolic order of the world, to be retrieved at the appropriate moment during a debate or long oration, the most elaborate memory aid ever constructed.”

This is almost the opposite of an imaginal memory palace: it’s an attempt to render the mind in the material realm, as a constructed object.8 It seems to me that this Theory-of-Everything thinking is the ultimate generalisation, the acme of the quote unquote Renaissance Man. (Imagine a time when it seemed possible to think that a person could know everything in the world— sweet Summer children!)

The structure of the mind, as far as I can tell, is only ever half-willed, at best. The foundations are laid well before consciousness of Self. The seed-shape, the baby-castle, is already part-formed at birth, and is then subject to massive adaptation in order to survive the helplessness of infancy. Then the child-mind is moulded by external influences. When we do learn to think for ourselves, form follows function: a mind is given shape by habit. Neuroplasticity means that those parts of the mind a person habitually inhabits grow more solid and more complex. It’s accretion, evolution, Von-Neumann-mind making more of itself— and there’s no way around the process, so we might as well make it interesting. My idea of a robust mind is one that is complex, original, and curious, tuned to the sweet spot between empirical reality and play. My theory is, that kind of a mind functions as inoculation against bullshit.

It’s not so much the specific content of the mind I’m trying to discuss, but rather its architecture: meta-structures, ways of knowing. Go deep enough into any craft or path, any study, and patterns of understanding begin to emerge. The visible products of craft or labour are a kind of by-product; the true work is the making of self. What we shape shapes us.9

I’ve written before about memory and oral tradition, here:

Star-Stories and Oral History

Barry Lopez: “Stories do not give instruction, they do not explain how to love a companion or how to find God. They offer, instead, patterns of sound and association, of event and image. Suspended as listeners and readers in these patterns, we might reimagine our lives. It is through story that we embrace the great breadth of memory, that we can disting…

In singing sessions these days, people sing off their phones: they look a song up on the Internet and let it go into their eyes and out through their mouth, this small front-of-face circuit like cigarette smoke trickled out the nostrils, and I want to say to them, if you don’t take the song inside your own flesh, how can it become a part of you? How can it be changed into a new thing that has never been made before? How can the song shape you from the inside out? You need to bite and chew and swallow the song, word by word. You need to walk with it and sleep with it. You need to fold it like a gold coin into your brain’s pocket.10 If you carry something inside your head then it IS you. Like Gershwin says, No, no, they can’t take that away from me.

Jack, at 80-something, sings with empty hands, in dialogue with memory. (He’s scornful of paper-words, even.) Sometimes mid-song he forgets, pauses; then the words come to him, he pulls the well-worn shining coin from his mind’s pocket and flips it into the audience. Personally, that’s what I’m aiming for.

Last week Rebecca Solnit wrote a post on social media:

”By the way the phrase is ON A TIGHT REIN, not reign, because it's about how you handle your horse with, you know, the reins, not about queens and reigns, and I keep seeing people get this wrong. One thing I think about often is how our metaphors, allegories, and analogies are mostly drawn from the natural world, animals, agricultural practices, and bodies, and how the more we live in abstracted digital spaces the more alienated we become both from the source of metaphor and the meanings of specific metaphors.

p.s. This is not a pro-tight-reining post, just a pro-accuracy one.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about how revealing metaphors are, how much they tell about the mind that makes them. In the act of writing, metaphors arise like bubbles; they just sort of appear. (I try to practice first thought, best thought; the most surprising analogy is the one that’s quicker than the censor.) In layering up all these disparate metaphors-of-mind, I’m trying to make a blueprint— not even a blueprint, more a rough sketch— of ineffable interior architecture. Trying to describe the shape of my mind in written words is attempting to spin starlight into cloth: a fairy-tale task. (What if instead of saying the mind is a building, I say it’s a coral reef, built creaturely? Or a forest— what if our minds are trees, linked root to root by a fungal web of mycelium?)

I said at the start that the most exciting kind of writing as a writer is the kind that comes alive and speaks back. That feeling of the words coming alive in your hands is like wet clay turning eel. There’s a shock, a spark— and urgency, to catch what the eel has to say before it wriggles back into the water. It’s work that takes full attention; that particular fish will never come again.

Sofi Thanhauser says, in Worn, “Text and textile come from the same Latin root, texere, which means to weave.” Writing is knotting word-nets, while my fingers are nimble enough and my sight clear enough. The mind-palace, however infinite it feels from the inside, is ultimately built of tender grey matter inside an eggshell of bone. Wander its winding hallways while the blood pumps, send us a letter, show us what you made; there’s no knowing the day of destruction.

Or is it more like a compost heap? Anyway, the written pages are not the point: the processing is the point.

This speech is also the source of ‘The Angel in the House’— the too-nice feminine self Woolf says we must murder in order to write. Woolf: “It was she who used to come between me and my paper when I was writing reviews. It was she who bothered me and wasted my time and so tormented me that at last I killed her… Had I not killed her she would have killed me. She would have plucked the heart out of my writing.”

There is a jerk on the line: “The imagination comes to the top in a state of fury.

‘Good heavens she cries - how dare you interfere with me - how dare you pull me out with your wretched little fishing line?’ And I - that is, the reason - have to reply, 'My dear you were going altogether too far. Men would be shocked.' Calm yourself I say, as she sits panting on the bank - panting with rage and disappointment. We have only got to wait 50 years or so. In 50 years I shall be able to use all this very queer knowledge that you are ready to bring me. But not now.”

Woolf was speaking in 1931, when Le Guin was two years old. Le Guin wrote this essay 57 years later, when I was eight. Is is time yet— is it time to use all this very queer knowledge from out of the depths?

Susanna Clarke’s amazing fantasy novel Piranesi, set in an infinite series of stone halls full of statues, with clouds, and oceanic tides.

The subconscious foundation of the mind— the dreamspace where strange creatures move in the invisible depths.

From Wolf Hall— itself a kind of portrait of the inside of Cromwell’s (imagined, reconstructed) mind:

“In Italy he learned a memory system and furnished it with pictures. Some are drawn from wood and field, from hedgerow and copse: shy hiding animals, eyes bright in the undergrowth. Some are foxes and deer, some are griffins, dragons. Some are men and women: nuns, warriors, doctors of the church. In their hands he puts unlikely objects, St Ursula a crossbow, St Jerome a scythe, while Plato bears a soup ladle and Achilles a dozen damsons in a wooden bowl. It is no use hoping to remember with the help of common objects, familiar faces. One needs startling juxtapositions, images that are more or less peculiar, ridiculous, even indecent. When you have made the images, you place them about the world in locations you choose, each one with its parcel of words, of figures, which they will yield you on demand. At Greenwich, a shaven cat may peep at you from behind a cupboard: at the Palace of Westminster, a snake may leer down from a beam and hiss your name.

Some of these images are flat, and you can walk on them. Some are clothed in skin and walk around a room, but perhaps they are men with their heads on backward, or with tufted tails like the leopards in coats of arms… Some speak, some quack. He keeps them, in strict order, in the gallery of his mind’s eye.

Perhaps it is because he is used to making these images that his head is peopled with the cast of a thousand plays, ten thousand interludes.”

This passage implies the plotting of a mental schema onto real-life geographies, rather than imagined ones.

There is something in this jumble of vivid images that evokes the mind well— the way disparate things rub up against each other— more than any ordered structure.

For the purposes of oratory. There’s a whole strand in Greek thought that holds that writing things down is inferior to remembering them. The Ancient Greeks, when they read from a written text, read aloud.

If the Theatre of Memory was built at all (some think it was, some think it wasn’t: Camillo went to France to build it for the King, but everything went wrong), it didn’t survive long, leaving us in the position of retrospectively reconstructing in imagination the structure that was meant to render the mind as a material object.

Stone-carver Ben says “The man shapes the stone and the stone shapes the man.”

“The sweet spot between empirical reality and play” <3

Thank you for all the fishes herein