The City is a Body, You are a Group of Apes

On Defoe's Journal of the Plague Year; London, where I've never been; and Wellington, where I have

Sideways History

In October of 2021, deep into Covid Year Two, I was re-reading and publicly riffing on Daniel Defoe's A Journal of the Plague Year. A novel in the form of a diary, written in 1722,1 it is set in the time of the plague that devastated London in 1665, when Defoe himself was around four or five years old. (Surely that’s old enough to remember?) It's a convincing reconstruction, written as if he had been an adult instead of a child at the time.2 The protagonist is named only as ‘H.F.’3

Dermot Kavanagh: “Defoe intended the book as a warning. At the time of publication there was alarm that plague in Marseilles could cross into England. It is a kind of practical handbook of what to do, and more importantly, what to avoid during a deadly outbreak.”

Talking about history was a good way to speak sideways to the present. I was curious about the often uncanny similarities between one plague and another. The rich fled, the poor kept working. People who could afford to locked themselves in their houses with stores of food, baked their own bread, brewed beer. Butchers had customers drop their coins into pots of vinegar. People socially distanced: it was understood that the sickness was transmitted by vapours, smells.4 Masks were worn. The streets were eerily silent and empty. Quacks, superstitions, and snake oil proliferated. Health professionals worked on until they dropped dead. The dead were thrown into mass graves.

This is how A Journal of the Plague Year opens: “It was about the Beginning of September, 1664, that I, among the Rest of my Neighbours, heard in ordinary Discourse, that the Plague was return'd again in Holland; for it had been very violent there, and particularly at Amsterdam and Roterdam, in the year 1663, whither they say, it was brought, some said from Italy, others from the Levant,5 among some Goods, which were brought home by their Turkey Fleet; others said it was brought from Candia;6 others from Cyprus. It matter'd not, from whence it came; but all agreed, it was come into Holland again.”

(As for us— I said— we could say, "It was about the Beginning of January, 2020, that I, among the rest of my Neighbours, heard in ordinary Discourse, about a new Virus spreading in China...")7

It matter’d not, from whence it came… The boundaries of the city, the body, have been breached, and the invaders are within the walls.

A Philosophical Aside: City as Body.

I'm reading as I'm sharing— I wrote, of the Plague Year— I don't know what's coming next. (Although I do know, and so do you. Judge the book by its woodcut cover, a skeleton holding aloft an hourglass and an arrow, an angel with a whip and sword.) I'm sharing as I'm reading, we're following together this story that is already spun, woven, folded up and buried long ago. We're digging it up and looking at the pattern and laying it next to the garment we wear now, to see what's the same, what's different.

In London in the 1600s most people were illiterate, so signs advertising businesses often had an image or a sculpture as well as a name. (This practice remains in the form of pub-signs, with their pictorial paintings, their image-based names.) I open up the book of London to see what Peter Ackroyd has to say about signs, the language of imagery. (London- the Biography: a book like a tombstone, 822 pages long). Folded inside the pages I find my lost notes for the magic meta-map of my own city.8 Ackroyd probably has a lot to say about signs, because he has a lot to say about everything, but the relevant nuggets are buried in the book, which is structured in an eccentric, meandering way. I find myself wandering in the pages like a lost bumpkin, unable to find my way to the right place.

While looking in the index for Signs, though, I see instead 'Plagues,' and turning to the appropriate page, see that it's just two pages ahead of the bookmark I left when I stopped reading a few years ago.9 (Like chewing through a loaf of dense bread, it was.)

Ackroyd: "Within the texture of Defoe's prose London becomes a living and suffering being... London is itself racked with 'fever' and is 'all in tears'. Its 'face' is 'strangely altered', and its streets circulate 'steams and fumes' like the blood of those infected... Daniel Defoe knew London very well— perhaps better than any man living in his period— and he declared that 'the strange temper of the people of London at that time contributed extremely to their destruction."

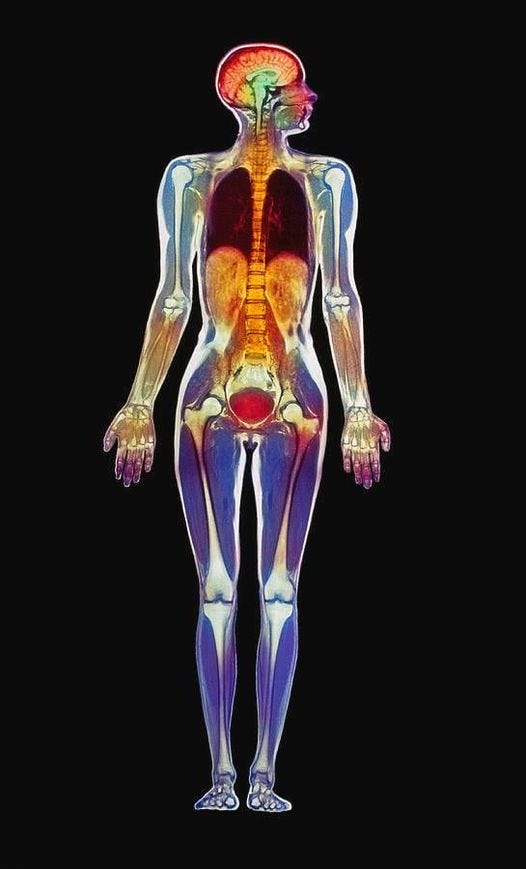

This is not the first time Ackroyd uses the analogy of the city as a human body: he opens the book with the same metaphor. "The byways of the city resemble thin veins and its parks are like lungs... For Daniel Defoe, London was a great body which 'circulates all, exports all, and at last pays for all'... Whether we consider London as a young man refreshed and risen from sleep, therefore, or whether we lament its condition as a deformed giant, we must regard it as a human shape with its own laws of life and growth… London is a labyrinth, half of stone and half of flesh."

The Plague, how very mediæval, yet how very modern. The New Plague, travelling not at the speed of a horse or a ship, but the speed of an aeroplane, skipping continents like a stone. In response, we go back in time. Cities are enclosed within walls. Towns withdraw their tentacles. Houses close their doors. Who you are with is who you are with. We are telling stories with the other pilgrims to while away the time.

In chaos magick we find the concept of an egregore: a group-mind, an entity or thought-form that arises from the collective consciousness of a group of people and attains a kind of independence of being. It can be intentional or unintentional. What is a city if not a type of egregore?

As the human mind and body interact, argue, collaborate, so the City's 'body' (its matter, its buildings, beings, and structures) interacts with its 'mind' (its mood, thoughtforms, cultures.) Is the group-city actually 416,828 personal cities intertwined? Or are the citizens neurons and ganglia of one big urban brain?

If the city is a body, what is your function? Are you a blood cell, a brain cell? Are you a bacteria, a bioflora? Are you a piece of bone, or skin? Are you serotonin, dopamine, adrenaline? Is a Wizard a psilocybin molecule?

If the plague has shown us anything, it's that all human bodies are one body. That our selfhood is to be a group of apes. Contagion is a mighty leveller. No one is an Island, intire of themself, to bastardise Donne. The space between our body (individual, personal, inside our skin) and our Body (collective, impersonal, the droplets exhaled / inhaled, the cells exchanged) is a territory we all must navigate.

Mark Doty: “You’re the shore on which an ocean of air is constantly breaking, in waves of breath. ‘Inside’ and ‘outside’ of lungs, permeable boundary of skin, eyes, ears, nose, holes in the body for substance passing in and out, no stable and fixed entity that is you, but a moving set of points through which pass water, air, light, food, parts of the bodies of others…”

Close to the Bone

Yesterday I had my shoulder X-Rayed. By caution and luck, I've incurred very little body-damage over my lifetime. No known breaks, no major wounds.10 Therefore I've had few opportunities to see my insides. (The only X-Ray image I can pull from the mental archives is of my teeth: the way the photo unbends the jaw's hook and lays it out flat on the film.)

My shoulder was even more angry than usual about being made to pose.11

Afterwards I asked if I could look. When I saw the images of my living bones, a wave of awe-joy flooded me: the skeleton is a ubiquitous motif— Death in the Tarot, dancing with a scythe— but this skeleton is mine, my individual architecture laid bare, the beams of my house. Ribs, vertebrae, clavicle, knob of humerus. (I’ve drawn a human humerus before, I know that bone.) Dapples of what I guess is my lung. Self-ghost.

While I waited for the bone-photos to be put onto a USB stick, the TV in the waiting room played a daytime soap scene in a hospital: a Doctor and a patient facing off across a desk. Behind the patient, a chart of musculature: a flayed human, fore and aft. I could see by the actor’s faces that they were British, not from around here. I’m afraid I’ve got some bad news.12

A door opens from the territory into the map. From the real waiting room into the simulated one. From the real human body to the anatomical chart. From the metaphor of the city's body, with its illustration of a see-through person, to the downtown radiation chamber that let me see into the hidden room of my chest. Doors are everywhere. I've never been to London, but Swami Bakveranda has a saying: How do you get to London town? One foot up, and one foot down."13

A busy year, 1722: Defoe also wrote the novels Colonel Jack and Moll Flanders, and the instruction manual Religious Courtship. He had less than ten years to live. As I transcribed sections of Plague Year from a Penguin paperback into my computer, I got a feeling for Defoe’s electric, poverty-induced writing style; the gallop of the dip-pen chasing thought, the sentences spilling out of their bounds. (The comma is his darling.) Dermot Kavanagh’s take: “He writes in a heightened, emotional state about the suffering of his neighbours.”

H.F. are the initials of Daniel Defoe’s uncle, Henry Foe, so some people think it is based on his reminiscences, as well as mortality bills, survivors’ written accounts, etc.

The sudden awareness of breath, of vulnerable mucous membranes— the intimacy of the naked mouth.

The Levant is the Near East: modern day Israel, Lebanon, and Syria.

Candia is modern day Crete.

In late January of 2020, I was at a friend’s house in Auckland. The virus was just beginning to seriously hit the news. The seven-year-old was pestering me to play a game called ‘Pandemic’, that he’d been into for a while. He tried to explain the rules to me, but I didn’t understand. I didn’t want to play, it made me uneasy. I thought, ‘That’s a bit close to the bone.’

Subsequently, from those unearthed notes, in March 2022 I constructed the Stone Tarot, of which more anon.

I alternate between wanting to read about England, and being sick of reading about England.

Touch wood. My theory about what’s going wrong now is that I’ve gone past my use-by date, into caveperson-obsolescence.

A few years ago I had my first stitch. I knew by the way it felt when I bumped it (the deep tug of wrongness, like a subterranean bee sting) that it had never happened before. I had no sense-memory of ‘stitch in skin.’

The energetic Cockney physiotherapist who referred me for the X-Ray told me my shoulder joint is ‘grumpy.’

I realised suddenly that the reason bad acting is unconvincing is because of the huge area of the human brain dedicated to paying minute attention to the constant weather-changes of the forty-three muscles of the human face. Our animal self smells immediately that the bad actor is lying. Maybe good actors are those who whole-heartedly convince even themselves.

‘Me haere pehea ki te taone o Ranana? Ka haere pakituri.’ (Ad hoc translation by Susan Powell. She said she couldn’t adequately translate the second half, ‘one foot up and one foot down.’ My guess: you get there on the waewae express.)

If you cross the right palm with enough silver, thoroughly evacuate your bowel and gulp a radio contrast dye, you can have your entire colon gently inflated and then passed through an X-ray CAT scanner which collates a three d image of the internal landscape inside a computer that the diagnosing physician (gizzard wizard) can virtually fly through. Special goggles and electronic overalls recommended, no doubt.

My mind stretches your metaphor and thinks of cancer cells. As malignant as the virus but generated from within the body rather than entering it.

Loved this, thank you