Kenneth Grahame, Wind in the Willows: “He gave the name of the station that he knew to be nearest to the village of which Toad Hall was the principal feature, and mechanically put his fingers, in search of the necessary money, where his waistcoat pocket should have been. But here the cotton gown, which had nobly stood by him so far, and which he had basely forgotten, intervened, and frustrated his efforts… At last— somehow— he never rightly understood how— he burst the barriers, attained the goal, arrived at where all waistcoat pockets are eternally situated, and found— not only no money, but no pocket to hold it, and no waistcoat to hold the pocket!

To his horror he recollected that he had left both coat and waistcoat behind him in his cell, and with them his pocket-book, money, keys, watch, matches, pencil-case— all that makes life worth living, all that distinguishes the many-pocketed animal, the lord of creation, from the inferior one-pocketed or no-pocketed productions that hop or trip about permissively, unequipped for the real contest.”

Here’s me: sitting on the Kāpiti Line train as it idles at Wellington Station. I’m eating a supermarket muffin, purely as fuel, so as not to turn up to the party starving. The muffin is stuck to its paper cupcake cup, and I am also discovering, as I break it open, that it has a centre of semi-liquid ‘apple’. These factors make it an unstable food— akin to an overstuffed burger— so I’m eating it in a hurry, just to get the eating over with. Because of the poor muffin-design, crumbs fall on the train floor. Large crumbs: small chunks, even. There aren’t any sparrows on a train.

I bought it in a hurry, whisking through the doomed train station supermarket, unable to find anything I really wanted to eat. It strikes me suddenly that this apple muffin is a small, inferior version of the apple pies Kev and I have been lately making with the apples from his tree (me peeling them in continuous red / green spirals, Kev cutting the codling moths out and chunking the pale flesh up into geometric slices, our hands sticky with apple juice). Kev’s pies, though, are masterpieces. Flour / sugar / egg / butter; enclosing wet apple substance: that’s where the similarity to the muffin ends.

Later at the party Tim, who has brought a pumpkin pie, asks if we made a pie for π-day (the fourteenth of March, 3.14 by the American system of date-numbering); as it happens, we unknowingly did.

The trains, unlike the buses, mostly run like clockwork. On the way down the station platform I’d noticed something about the clock-face: it lacks a second hand. The two hands stay still, then the minute hand ticks over to the next minute.1 I noticed this because I happened to be looking at the clock just as the minute hand leapt forward to the next minute-mark. (The platform clocks are nostalgic relics; the time is displayed on the digital timetable boards.)

As the minutes tick down to departure, a tense scene unfolds inside the train carriage, played out at the proscenium of the carriage door. A man leaves his baggage onboard, steps off the train, and disappears back along the platform. As the train begins to make signals that it is preparing to leave, the young woman he’s left behind with the things becomes more and more anxious. She gets up, sits down again, talking to herself about what the hell he’s thinking of, gets up again, flits to the door and looks out, calling his name. Her anxiety is contagious: it catches hold of me. I hate being late. Maybe it’s because of relying on public transport: being a passive traveller rather than an active one. (For instance, the reason I’m on this train and not the one before it— the one I’d intended to catch— was that my initial bus came fifteen minutes late. The Metlink website still pretends one can plan one’s journey by its timetables— THIS bus, then THAT bus, then THIS train— but I know from experience that the buses in particular are not to be relied upon.)

I’m watching as if it were a tiny play. The couple look down-at-heel, and I wonder if the man’s evasive action is the knee-jerk defiance of the disenfranchised— a double fuck-you to the train’s rigid time-keeping and the partner’s anxiety. But when he returns, strolling nonchalant along the platform and through the closing doors, I think that maybe he went to hunt for something he had left behind. I don’t know, exactly— both because the plot tension has been resolved by his returning in time for the train not to leave without him, and because I have now transferred my attention to the youth who has appeared in the seat facing mine: a sideways-seat, that is, one with its back to the wall. (I don’t tend to sit in these seats because they’re not optimal for looking out the window, but I remember that when I rode the train to school every day I favoured them. When repeated exposure renders the view repetitive, the interior of the train becomes more interesting than the outside world, maybe?)

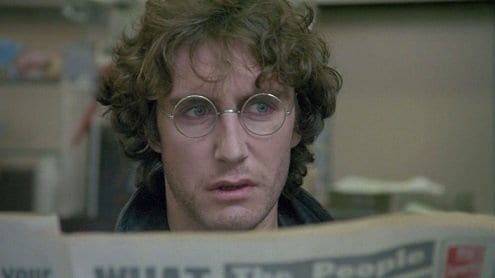

The youth is wearing a pair of Lennon glasses with one red lens and one blue lens, as if this can render another dimension visible.2 His darkish, centre-parted hair is down to his shoulders, curling at the ends a little. He’s dressed in layers upon layers: t-shirt, flannel shirt, waistcoat. Canvas cargo pants and a denim jacket, both brown. A light overcoat, blackish. Nike sneakers: red, black, and white. Chains around his neck— over the t-shirt but under the flannel shirt— and a couple of rings on his fingers. The overall effect is of different time-layers mashed together: a kind of Doctor Who look. He’s old enough to have five o’clock shadow, but only on his lip and chin; otherwise he’s pretty as a girl. However, there’s a slight grubbiness to coat, jacket, and trousers— as if he’s done stuff in this outfit, he hasn’t just sat around indoors— and every pocket is bulging. He has a McDonalds bag, and is throwing fries into his mouth.

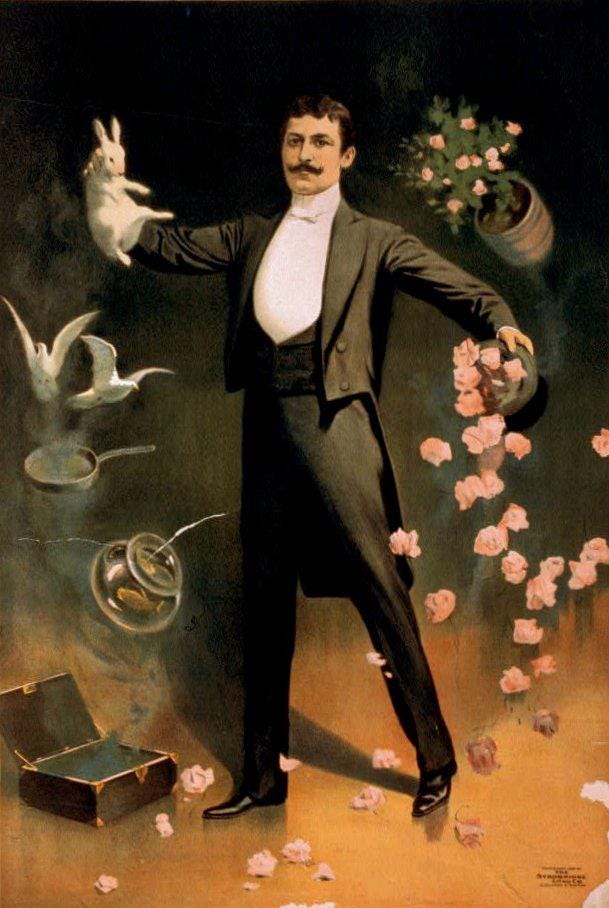

Suddenly the platform is slipping past the window. The youth is as aware of me as I am of him— he’s spotted me as a fellow weirdo. As the train pulls out of the railyards and alongside the harbour, he finishes his burger, stands up and takes off his overcoat, rolling it into a loose ball and placing it on the seat beside him. The coat lining is thus revealed: the kind of cupro that manages to be both dark red and pearly grey at the same time. I’m watching him from under the brim of my hat as he puts on a little show for my benefit. He begins producing items from one of the inside pockets of his jacket. A box of what looks like mechanical pencil leads. A small portable chess set. A little round pot of what looks like black ink. A spotting scope. Two decks of cards still in their cellophane.3 A screwdriver. Some vape paraphernalia. A bag of Fruit Bursts. He stacks these objects on top of the rolled overcoat and makes a steadying motion with his hands like Whoah— this pile is so big I have to stop it from toppling over!

I can see that his other inner jacket pocket is similarly packed— I glimpse fluorescent yellow, possibly a bundle of highlighter pens— and the cargo pockets of his trousers look equally stuffed. So I’m given to understand that this is just a fraction of everything he could produce, if he cared to. From one of these other pockets he produces a can of blue V, the colour of a glacier, and taps it with the backs of his fingernails, to make ringing tones. He’s combing his hair with his fingers, singing along silently to the music from his headphones. I’m very curious to know what he’s listening to: I feel it could be almost anything.

I remember phases like this, when I enjoyed going out without carrying anything, walking with everything I needed in my pockets.4 The feeling of lightness combined with preparedness. I think, too, of Ötzi, the Iceman, carrying his entire kit as he walked: axe, tinder, string for mending, flint knife, bow and arrows, antler retoucher to sharpen them, etc.5

Suddenly I remember my initial idea for a Wizarding coat: it would have many small internal pockets from which one could magically produce almost anything anyone needed— lighter, earplugs, cough drops, condoms, safety pins. (“Like a World War Two black marketeer,” says Kev.)

I went hunting for a coat to upcycle into my vision, but it was October— the end of Winter— so the coats were being put away, and besides, I had no money; but after a lot of searching I found the perfect black wool coat in Op for Animals, for ten or twelve dollars. I cut the snake out of the little kid’s t-shirt I’d been hoarding for some years, and stitched it on by hand.6 I also changed the buttons, stitching on a semi-matched set assembled out of my button collection.

This coat was too form-fitting to accomodate internal pockets without spoiling the line, though, so I abandoned that part of the plan. Later I had my friend Deborah re-line the coat with red silk: the silk cost a pretty penny, but it was worth it, to flash the lining like a kākā flashing its red wing-pits.

Making this coat was my first Wizardly act, a way of hanging out my shingle. I stitched the last stitch and wildly synchronous things immediately began to happen. I understood then that it doesn’t matter if you believe in magic— it believes in you.

David Graeber: “Revolutionary action is not a form of self-sacrifice, a grim dedication to doing whatever it takes to achieve a future world of freedom. It is the defiant insistence on acting as if one is already free.”7

At the party, five or so people ask me about my hat. I’ve worn the hat a lot over Summer, and usually a few strangers comment on it, but this level of interest is unprecedented. The new element is the peacock feather I stuck in it before leaving the house. (I found this feather on the other side of the empty section at the back of Kev’s garden last week. There are feral peacocks that roam around over there, and although I didn’t see them, I found three of their feathers. I also found some huge oyster mushrooms up a dead cabbage tree, but I couldn’t reach them. I stood there gazing up longingly, like the fox and the grapes.)

People want to know:

Where did I get the hat? (My friend Marina made it for me.)

How is it made? (Crochet.)

I test a garment by its effect in the world.8 In this case, the feather was the magic touch. Wizarding can be seen as social science, in the sense that the city is a field upon which patterns are played out; one can generate a subversive magical ripple by means of simple things like anachronistic dress, manner, and behaviour.9 That’s what I was doing, and that’s what the youth on the train was doing, each in our own sphere of operations. We didn’t speak to each other, or even look directly at each other.

He was evidently some sort of a baby Wizard, beyond a tadpole— more like a froglet, with legs and a tail. Honestly, my thought was Son, you’re in the wrong decade. He would’ve fit right into the 1990s, when I was his age. He reminded me of certain friends I had then. But— I also thought— there’s a danger to being that kind of a bright young spark. The eccentric kids, the ones who won’t or can’t knuckle down to conformity… life isn’t always kind. Eccentricity is a personal quality some people grow out of and some people grow more into; maybe the underlying factor is the stubbornness of one’s contrarianism.

In any case, behaving in such a way in one’s late teens in a world like this one bespeaks some sort of kind cocoon: Steiner School, maybe, and / or loving parents. May you become a fully fledged frog, my young friend! The world needs more Wizards!

The train crests the hill and begins its descent towards the Kāpiti Coast, threading the tunnels, light dark light dark light. The golden sun on the sea, the high view of the islands, magic lands: Kāpiti, Mana, Te Wai Pounamu. The young Wizard is looking at his phone, which I find only mildly disenchanting; the phone is only one small hoof-pick in his Swiss army knife of a rig, and as such, far less potent.

I hope that he will get off at the same station as me— Paekākāriki— but he stays on. (Only possible destinations: Paraparaumu, Waikanae… Or— remote possibility— riding to the end of the line and back, as some sort of Debordian dérive.) As I disembark, he’s absorbed in scratching dirt off his pants with the side of a pair of blue-handled scissors. I look into the carriages as the train pulls out of the station and give him a wave, but he doesn’t see me.

In my dreams this story changed its skin. I dreamed of a hat with a jewel-green hummingbird at the crown, its wings a blur. I put my ear to the interior of the hat and could hear the hum; but when I looked at the tiny bird more closely, and put out my hand to feel the tips of its wings flutter against my palm, I saw that it was not alive— it was running by a tiny motor.

Next I was trying to get myself and three friends into the pools. (The echo of people’s voices, the blue wobbling light.) If it was just me, or even me and one friend, I could swipe my card and get us both in for half price, but I was reluctant to cheat the system in a bigger fashion for fear of getting busted, so I was trying to sign us all in above-board, filling in forms on a computer’s touch-screen.

Machines in dreamland don’t work— logic is not the strong suit of the subconscious. The questions became more and more nested and arcane. I just want to get everyone into the pool, for fuck’s sake! Then I noticed a box I hadn’t seen before. Ah! I’ll tick that I’m a McGillicuddy10— that will make for more interesting questions!

It reminds me of how my Dad, a clock obsessive, sets his timepieces to the start of the long (sixth) beep on National Radio. He loves clock time, I hate it: go figure.

A sleight-of-hand indicator: doing a magic trick with an just-opened deck proves it hasn’t been tampered with.

This was only possible when I didn’t need to carry my journal 24 / 7. My current phase requires access to book, pen, and ink at all times: I carry a satchel. Last week I went to a gig where I was seated on the other side of the room from my bag, and I could feel the umbilical tug of it viscerally— I was Jonesing for my book. My journal is my workplace and my archive. The possibility of losing my current journal volume (*AVERT*) is literally unthinkable.

Phil from Shanty Club solves the notebook / bag equation by using a pocket-sized notebook and a tiny fountain pen. From my point of view that’s better than nothing, but really only suitable for jotting ideas. Last night at our mutual friend’s wake I met Liz, who makes tiny book earrings and pendants. She said that someone who wants to write their memoirs could use her tiny books to write extremely minimal ones. Depends on the pen: John, sitting on the other couch, showed me a few of his fountain pens— a bullety Mont Blanc, and a translucent Pilot Kakuno with a very fine nib that he uses for writing physics equations.

More on Ötzi’s kit here: https://www.iceman.it/en/equipment/

Once or twice I’ve seen a kid wearing the t-shirt, which has the snake’s head on the front rather than the back. I’m always like Yo! Little Wizard!

I got this quote from Maggie Nelson, and hunting its source, found that it came from this essay: https://davidgraeber.org/articles/on-the-phenomenology-of-giant-puppets-broken-windows-imaginary-jars-of-urine-and-the-cosmological-role-of-the-police-in-american-culture/

(Note the collapsed-number clock favicon— synchronicitous!)

You have to be in the right mood for dressing up: eccentric fashion attracts attention— you have the same little conversation repeatedly. Wizard Coat Mark II is far more understated.

See also: this great piece by Peco and Ruth Gaskovski— Sowing Anachronism: How to be Weird in Public, and Private

The party I was travelling to on the train was a McGillicuddy party. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/McGillicuddy_Serious_Party

no word of a lie—i have been putting serious work into figuring out how to make waistcoats the load-bearing center of my wardrobe for weeks now, based on a similar ethos.

not because i'm trying to cosplay. the practicality of it is more enchanting to me than any kind of social signaling. i do care about what other people think; the libidinal pull toward getting the whole assemblage rigged up juuust right is much more immediate. especially now that i am blessedly approaching middle age and have kids of my own to embarrass.

also seems much more humane to warn people visually, like a poison dart frog: if i dressed in jeans and a polo shirt, people might think i'm prepared to talk about Ted Lasso, and then be horrified to find me incapable of ordinary small talk. like one of those bells they made people with leprosy carry around.

so yeah: pockets, more pockets, watch pockets; waistcoat, jacket, overcoat, satchel, linings full of sigil-stitches. these are my goals.

Your writing inspires me so much! Thank you!