He kūkū ki te kainga,

He kākā ki te haere.

‘A wood-pigeon at home, a parrot when travelling.’

A somewhat ambiguous whakataukī / proverb;1 however you cut it, people behave differently when they leave their village.

I’m heading North for Tradfest, lugging my suitcase and bags, wearing a new wide-brimmed hat that threatens to blow away, carrying my coat over my arm. Thus laden I feel like a traveller through time as well as space— as if I might embark upon a steamship instead of a train, handkerchiefs fluttering on the quayside.

As the bus swings down Brooklyn hill towards the city I look across into the tall treetops of Central Park. I know I will see a kākā, and sure enough, one appears, separating its wide-winged silhouette from the dark foliage for a moment. The bird-magic is with me.

In the train station underpass— a hotly contested busking pitch— I hear a voice singing high and pure, “Hallelujah, hallelujah.” A young person is sitting cross-legged, back against the wall, an ukulele in their lap. Even as I come closer I can’t hear the instrument at all, only the voice, resonating as in a church, and I look again to be sure the voice is coming from them, from such a small slouched body. It is: they are reading the lyrics off a phone balanced on their knee.2

I go to buy my ticket. The open echoing chamber of the train station, evening commuters pouring out of the city to their trains, hard shoes ringing, the rush and flow. The person behind the ticket window writes the ticket out by hand— carbon copies, each one stamped— then tears it from the book and slips it under the glass. The pastness intensifies. While I wait for my ticket I hunt through my satchel for gold coins to throw into the young singer’s hat, but when I go back into the tunnel they’ve vanished. A new guy is setting up, with a whole lot of gear, amps and mikes and a guitar. I stand there uncertain what to do, whether to wait and see if he’s any good, or whether to go read my London Review of Books and watch for my train to come in. The old man selling woven mats is watching me, and beckons me over. “You look lost,” he says.

“I’m not lost— I just have an hour to kill.”

The mat-man is sitting in a little alcove, off to the side of the river of foot-traffic flowing through the tunnel. Glasses, white hair, white beard. His sign says ‘Turk’s head knot mats.’ He has made a display: the mats are tied to the railing with string. They’re beautiful, open-holed Celtic knot-forms, woven in jute— thick rough brown rope. He has the same oblong knot-form embroidered on his cap, and on the breast of his hoodie, over his heart. Also his name, which is Steve. Now that I’m close, I can smell the antique, maritime smell of the jute.

A homeless guy is sitting in the alcove beside us, morosely smoking a roach. Steve whispers to me that this dude is a frequent problem for his business, queering his pitch. After a while, though, the guy gets up and shuffles off again.

“What’s your axe?” Steve says, pointing to my case.

“Clothes,” I say. “Not an instrument— it’s my clothes.”

“You are a musician though, aren’t you.”

“Yep. I’m a singer.” It’s noisy: I mime ‘singing’ with a hand running up my throat and fingers spreading in front of my mouth.

Stroking his big white beard, he tells me he once sang with the Vienna Boy’s Choir, when he was young, in Napier.

I tell him I’m on my way to a folk festival. When he hears folk, he hands me his phone so I can listen to a piece of music. “Go on, hold it right up to your ear. It’s not long, five minutes.”

I hold the phone up under my hat, bend my head to pay attention. My bags are heavy. After a few minutes of this listening pose the straps make my shoulder ache, but I don’t want to put them down on the dirty ground.

This is the piece:

He tells me how he has to weave the mats as therapy for his brain, which was taken from him by a drunk driver. “I was T-boned,” he says. “I went through the windscreen of a Kombi.”

The new busker has started now, and Steve points out that he sucks. “I used to be a soundman. He’s not playing to the space.”

Me: “Where does the knot end?”

“It begins and ends in the same place.” He turns a mat over to show me how the end and the beginning lie side by side behind a crossover, how the cut ends are dipped in clear nail polish then whipped so they don’t unravel.

He tells me he’s a Shetlander. “Me too,” I say.

“Square palm? Show me your hand!” he says.

I hold up my hand, and he holds up his. “Yep, you are. Square palm.”

Me: “My Mother’s Mother’s Mother’s Mothers…”

Steve: “My parents came here in the 1950s.”

Me: “Oh— you’re a proper Shetlander.”

Anyway, he says, he needs to make money because he needs to get his dog’s nuts chopped off. He shows me dog photos on his phone. Two dogs, draped over each other in various lazy poses. “Guess what their names are.”

The dogs are golden, sandy-coloured.

Me: “Um… Biscuit and… Cracker.”

Steve: “Bonnie and Clyde!”

“I was close!” I say. “B. and C.!”

He tells me one is a kelpie-cross and one is a labrador— that’s the boy-puppy who needs his balls dealt to. Steve reckons the operation will cost $450.

Me: “You’ll have to sell five mats.”

He commences a sales pitch, telling me how much they cost to make— materials, time— offering me a special price. It’s not the hard sell, more just a continuation of our yarning. I say that his original price is very fair for the skill and labour, but I’m heading away.3 They’re beautiful objects. In my mind I transplant them into a magazine-spread interior, a seaside bach, a city apartment. The commuters who don’t cast a glance are incapable of this kind of imaginative transition, maybe. I tell him I hope he sells lots of mats. Anyway, I better go to my train.

Outside, a gust of wind, a mist of drizzle. If my hat blows onto the tracks, goodbye hat: I take it off and carry it. I wait on the platform for the engine to be coupled, now desperate to put everything down and ease my aching arms.

Aboard, I gaze at an office worker seated across the aisle. Bureaucrats are so tidy. Every garment and belonging is expensive, of good quality; carefully chosen (within given parameters of choice). Haircut, glasses, socks, shoes, wedding ring, backpack, drink bottle. He has a can of beer sitting on the table in front of him.4 After a long pause he cracks it open— TSK-SSS— and I see that the train has just begun to move; maybe it’s a private rule.5

He takes a book out (good). A paper library book (good). I try to see what it is. He sees me staring, and smiles at me. After a while, as he reads, he holds the book up and I see the cover: Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms (ungood).6

I get to work transcribing my conversation with Steve. When I emerge from the page, I see that the man across the aisle also has a notebook out, and is writing in it. (Notebook: lined. Pen: blue ballpoint.) I write and he writes. We write. I think he will stop, but he doesn’t. There’s a kind of energetic dynamism that happens when I am not the only person writing by hand. We write away companionably for an hour or so.

When the train approaches Ōtaki, he stands to get off. Waiting for the train to stop, he asks me what I was writing. I tell him about my Substack, write the address in his lined notebook in my green ink. He says his name’s Sam, and we shake hands. He says he’s only just started writing, that he tries to write an hour a day. I say the main thing is just to keep going: you’ll eventually get somewhere. We’re speaking quickly now, the train is approaching the station. He admires my pen and I say it’s a Pilot— they’re pretty cheap.7

Sam: “Some of the writing was in another colour, though— red— what was that?”

Me: “Oh— that’s a song I’m trying to learn.”

Sam: “Did you write it?”

Me: “No, it’s from the 9th century.”

Sam: “From Europe?”

Me: “From Donegal— Ireland— translated from the Gaelic.”8

Suddenly I see myself— I get a flash of how I must look through his eyes: my new hat, tall and black, with a pāua shell sewn on the side— my long black coat with its thick fur collar— my long plait, my boots— my battered vintage suitcase— my work, the green script on the cream page— talking about the learning of Mediaeval songs. I am heading to the forest to sing.

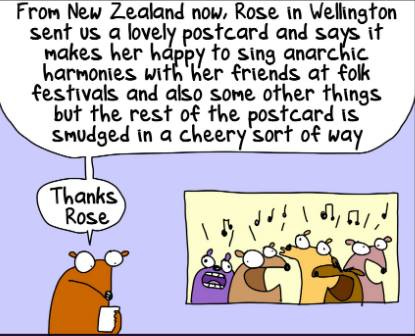

I remember the time I sent a postcard to First Dog on the Moon. He asked people to write and tell him what made them happy. Just like seeing the kākā, I knew he would include me, and he did:

Later, Kev tells me he saw a three-legged greyhound in town. “This woman had two of them— a seven-legged pair of hounds.”

Me: “It’s like a riddle: what has seven legs and can only half-catch a rabbit?”

Glitchy streetlight

Steady moon

Is the kākā louder? or better-dressed? or more sociable? or more of a show-off? or more demanding? or all of the above? than the kūkū?

If you have ancestral knowledge regarding this whakataukī, please enlighten us in the comments.

There won’t be any of that phone-singing business at Tradfest, I can tell you that for free.

They were beautiful mats and I intended to link to his website here so YOU could buy one, but of course he doesn’t have a website. You’ll just have to go to Wellington train station of an evening and try your luck.

They sell booze on this particular train.

Train go = beer o’clock

Sam, if you’re reading this, no shade. I know some people like that kind of thing.

This one: Inkt - Pilot Metropolitan

This one:

I ended up abandoning this song and singing ‘They’re Moving Father’s Grave to Build a Sewer’ instead— of which more anon.

Genealogical correction from my Mum: the Shetland line is my Mother's Mother's FATHER'S.