That subterranean eel the Tube train slips mechanically through its caverns, rattling its metal bones. My ears crackle and pop. Am I under the river now? Or— now? Between one and another of these stations, anyway, these names along a line, I am passing under the river, I am going South.

South is a resonant word, with different weightings in different places. Does South take you closer to the Equator, or further away? That is, does it lead to a hotter place, or a colder? In Aotearoa, South means Te Waipounamu, the South Island. (Colder.) There’s a cultural divide between the North Island and the South Island, reinforced by the physical barrier of Cook Strait. Going from one island to the other takes effort and planning, and there are those hefted to their own island, who never cross over.1 In London, the dividing line is the Thames, and a similar principle applies. As someone in Brixton said to me, “Oh, Northerners: we hate them, and they hate us.”

I wrote the first draft of those two paragraphs in London. I was going to write A Postcard about all the things that happened in Brixton, but I ran out of time. I’m now South myself, back in Southern Hemisphere Summer. Consider this, then, the postcard that I wrote on holiday, but didn’t get around to posting until I got back.

Speaking of postcards… I was walking between bus and train when I came upon a secret market underneath Charing Cross.2 I followed the tricky arrows on the low-key signs, which were pointing vaguely into mid-air. (The way in was insider knowledge, but all of this randomness and secrecy was catnip to a flâneuse. What luck that for once I had chanced on the right place at the right time!) After a few false starts, the arrows led me to a small door in the corner of two walls, then down a stairway to an underground carpark. There were a small number of people (who I would classify as enthusiasts) combing some ten or twelve stalls. Coins, stamps, enamel badges, cigarette cards, memorabilia and ephemera (embroideries made by soldiers, cartes de visite, letters in sepia copperplate— the kind of thing you’d die to find even one of in New Zealand), and… postcards. Jackpot! There were boxes and boxes of postcards, all jumbled in together. But as with so many things in London, it was an overwhelming embarrassment of riches. So many postcards, so little time!3

After a long yarn with a retired Scottish psychologist, I found a guy who had his vast postcard selection organised alphabetically, by county and then by city and village. Bless him! (Luckily I had learnt my lesson by now: I had twenty pounds in my purse for just such an emergency as this. Mostly it was no cash, no cash— but sometimes it was only cash, only cash. I’d be like, How about both?) I flipped straight to Kev’s village and chose the three prettiest cards.4

Photographing and uploading this postcard— of Kev’s river, the Adur— made me remember that on my last morning in London, on my way to mudlark downriver, I saw a girl on the bus, wearing a fox fur hat over her black afro, whose jacket said AWA: river in te reo Māori. This felt like the mighty Thames speaking to me, even when I saw that the embroidery actually read AWARDS, with the second half of the word hidden in a fold of fabric.

Emerging from the underworld into the colours of Brixton. Small lakes on the pavement from the rain. Murals on the walls. Fruit and meat and fish, clothes and records and beer, beggars and perfume. Cherimoya, pawpaw, melons, chillis, plantains, sugarcane, sweet potatoes, herbs. Drifts of market detritus, bits of which I felt were possibly still edible.5 Tendrils of sinsemilla— though that was not unusual in London. The brown knit silk cardigan heavily embellished with glittering russet-coloured beads that I immediately found in the charity shop for Maddy, breaking the op-shop curse that had dogged me North of the river.6 What I’m trying to describe, though, is the feeling of it, which was like Ahhhhh… So different from home, yet somehow homely, familiar. Brixton felt more like Wellington— more like New Zealand— than any part of London I had yet been in.

There was the amazing bookshop I found as soon as I stepped into the arcade, Round Table Books: a tiny space packed and stacked with right-on literature. When I arrived a young red-headed man was trying to decide on Christmas presents, his arms piled with books. I patiently waited for him to leave so I could get in: really there was only room for two people in there. After ten more minutes vacillating he left without buying anything, saying that he felt overwhelmed, and as soon as he left I stepped into the vacated space. I immediately spotted books from my country— Becky Manawatu’s Auē; my city, even— Greta and Valdin by Rebecca K. Reilly, which I went to the launch of; and a whole niche stuffed with Fitzcarraldo Editions’ beautiful white and blue— exciting!

I talked to the shop-person, Amber, for a good half hour or more. When I asked if she had Joey Connolly’s poetry book The Recycling, which I had been hunting for, she said she didn’t; but then she said if I liked poetry, I should check out Gboyega Odubanjo’s book Adam. I found it in the poetry stack in the window and read a few. It’s a posthumously published book of poems about a drowned boy, written by a poet who also drowned, and it punched me in the heart. She told me about a project she was working on, to do with park benches and sky-gazing, and I told her about the Stone Tarot I made to talk to my city. Upon discovering our mutual love of Ursula K. Le Guin, I showed her the badge on my lapel made by my friend Sam, Le Guin in profile like an Empress on a coin. Where can I get one? she asked. I’d had it on my jacket for a good year or more, but I have a spare at home, so I unpinned it and gave it to her, and she immediately pinned it on her jacket. (Good magic, forging a link across timespace.)

“Keep an eye out for Kae Tempest,”7 Maddy had said. I didn’t see them, but I understood now what had spawned them, and I bought their slender book On Connection for Maddy— we had talked about it the day before. (When I opened On Connection the next day at the table, I saw the epigraph by William Blake, a Proverb of Hell: Dip him in the river who loves water.) I also bought a book Amber recommended to me when I said I’d been writing about housing: All The Houses I’ve Ever Lived In, by Kieran Yates.

Amber had recommended a Caribbean-Guyanese restaurant nearby, but I was too hungry to walk, so I chose a place in the arcade that seemed busy. (Always a good way to choose somewhere to eat. For a further refinement, is the place patronised by people native to that cuisine, such as the Italian restaurant Leo and I went to in Brighton that was full of Italians? That’s the best indicator of all.) While I ate a burger and sweet potato fries, the man behind me merrily narrated his dog’s chaotic behaviour. (It was a camel-coloured chunk with one blue eye and one brown, both with an equally mad glint in them. I asked the owner what the dog was, and he said a ‘Frenchie’— a French bulldog.)

“Don’t you put your dirty paws on anyone! Except me, obviously.”

When the dog jumped up on a passing child— “He’s an attention-seeker! He does not bite, he does not bite, he does not bite in the slightest.”

“If you behave yourself, I’ll give you my sausage!”8 he said to the dog. Then— “Probably shouldn’t have shouted that out in the middle of the market, ha ha!”

Around the corner, I was lured into a vintage clothes hole by the rack of ten-pound specials outside. I could feel the potentiality, but also the canniness: likely no bargains, but possibly something I wanted. Inside the shop my eye lit on a pair of ankle boots, but when I picked them up they were (Balenciaga?) some many hundreds of pounds. The long-limbed, suited and hatted lounge lizard in the corner asked me if I liked them, and I said I did. What size are you? he asked me. A 41. They’re a 42, try them on. “I can’t,” I said, “Look at my foot—” holding it out in midair— “A Polynesian foot, too wide. We all walk around with bare feet.”

”Intriguing!” he said, and offered me a glass of wine. I wasn’t going to say no. “Look behind those jackets there, young lady.”

Underneath the neatly pressed hems were three wine bottles in a row. “The Yellowtail, the one with the kangaroo!”

He asked a loitering young person to fetch him some glasses (very rudely, I thought: I didn’t yet know the half of it). He told me that his name was Anti-Chris. We sat there drinking white wine. He told me a story about the time he dressed up in KKK robes and walked down Brixton high street. (The cross he had made by nailing two bits of wood together was too large to fit on the bus, so he had to walk.) This seemed like a suicidal action.

Me: “Did you make the costume out of a sheet?”

He said a friend had made it for him; she had worked from the official pattern.

He told me about the riots, too. A guy who was killed had been sleeping with his girlfriend, back when he was a drug dealer— I think that’s what he said. There was a scar on his cheek, like someone wearing a ring had punched him.

He showed me the silver jewellery he had made. Underneath the glass underneath our glasses, I saw something I liked: silver dice. He took them out to show me. They were heavy, cast in solid silver. Some had dots, but the one I liked best was a doubling dice— 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64. (He said this was the year of his birth, 1964.) When I asked how much he’d sell it for, he said that he’d have to sell it by the gram, so it’d be at least £100. I said I was too poor for that. He also had some solid silver backgammon pieces, one with a tiny cross in the centre and one with a tiny crescent.

Once in a while customers came in. He was consistently rude to them, and I saw that it was a compulsion he couldn’t control. He had certain phrases that he repeated— tics:

“Intriguing!”

“I concur.”

“Fuck off!” (Accompanied by a middle finger.)

“Are you an idiot?”

“Do you think I’m stupid as well as black?”

The only customer he wasn’t rude to was a dreadlocked, bearded young man who came in to buy a bracelet for his daughter. They called each other brother, and Anti-Chris gave him the bracelet for half-price, and hunted out a box to put it in.

Also, there was another young person who came in to talk to him about… (I think it was maybe cataloguing his jewellery, or something like that.) She had short brown hair and glasses, a baggy striped shirt and jeans: a particular look I recognised from home. She had used to work for him, and took his filthy teasing in good humour, affectionately, which made me think he was probably OK. He was a reprobate, but an entertaining reprobate, and he gave me wine. But he didn’t really listen, and as time went on he because bolder in his forays. While he was trying to button a Belgian Mum into a bright red 1970s dress and jacket combo (she bluntly said it wouldn’t fit, but he insisted it would) while the non-English-speaking Grandmother held the baby, I gapped it.

I had cut my thumb deeply with one of Josh’s lethally sharp knives the night before, while chopping the King oyster mushrooms I’d bought from a Sussex farmer at a market in Bloomsbury.

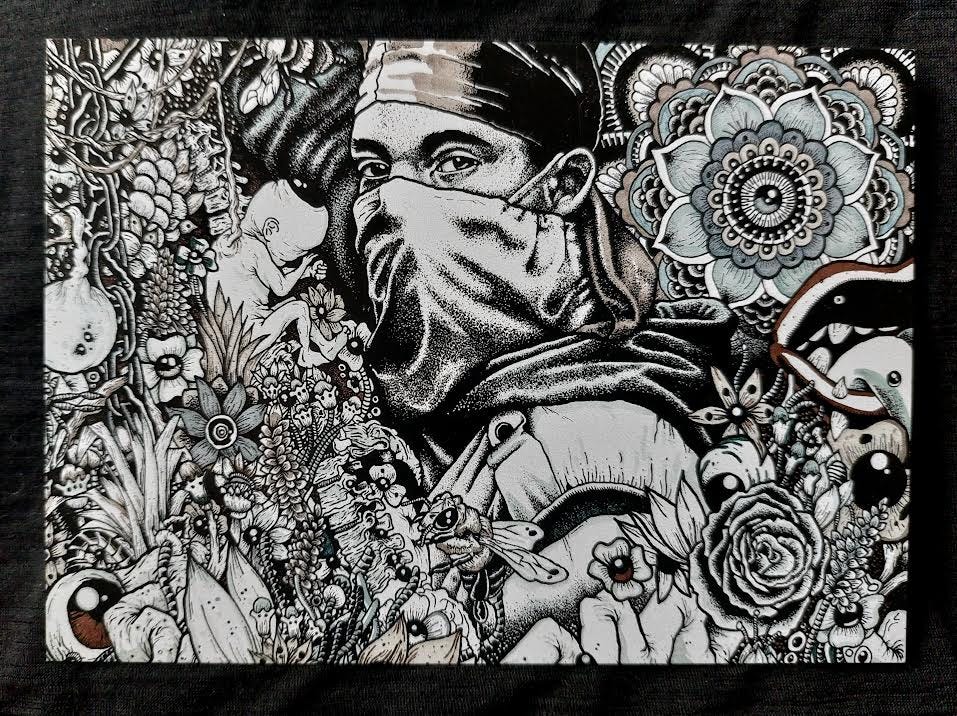

Now the plasticky Trolls plaster slid off and my thumb began bleeding again. I went into the nearest shop, which was filled with black and white photos, and asked the proprietor if he had a sticking plaster. He didn’t, and I said well, I would just have to not touch anything with that hand, then. But he searched his drawers, and wrapped my thumb up in toilet paper and duct tape: a black and white solution. (This act of care touched me, his hands attending to my hands.) His name was Wayne, and his shop was called A Celebration of Demonstration, and his photos were all of protests, which reminded me of my friend John Miller, who I told Wayne to look up. “There, I followed him! Now let’s see if he follows me back.”

The walls were layered with hundreds of small pieces of cardboard bearing hand-written political messages. I asked him if there were any from New Zealand. (I knew, for instance, that Ariki had been in Brixton not too long ago.) He pointed out an Aboriginal flag— close, I said, but not quite9— then one that said Toitū te Tiriti! We hung out for a long time, yarning about art and politics. He told me that when he was growing up, Brixton was mentioned in the same tones as Johannesburg or the Bronx. He told me that he started on his new photography path when George Floyd was killed. He was so angry, he had to do something, make something… We talked for a long time about the struggle of art, how to keep going.

Why were these people like my people? For one, it was because they were immediately ready to hang out for the sake of hanging out. (Ross Gay has a whole series of essayettes about the power of the hang.) In London at large, I talked to people everywhere I went, and I had many great interactions. (So much for the city’s unfriendly reputation!) I found that people mostly wouldn’t initiate— some would, like the little old Cypriot tailor I met on the bus in Soho, who told me to go to Savile Row and watch the tailors at work— but when I struck up conversation, they would mostly respond warmly.10

In particular, though, it was that the people in Brixton wanted to talk about the things that matter most to me. Their work, my work; art, politics, magic. (I think it was stylistic, too. The Brixton folk had a pride expressed through appearance and dress that felt Wizardly to me— that felt, frankly, indigenous.) Outside one’s own cultural matrix, inside someone else’s, it’s possible to experience a kind of diplomatic immunity. I was a guest there, but a welcome guest, is how it felt.

I could feel night was coming, the short Winter day was ending. Wayne asked me if I wanted to make a little placard for the wall— he had a basket of pre-cut cardboard rectangles, and a drawer of Vivids— and pin it up wherever I felt it should go. I loved this thing he had going on, where every visitor left a record of their heart on his wall. I recreated some of the posters I’d made in Sasha and Achille’s show: THE REAL WORLD MISSES YOU, I wrote, and DREAMS ARE FREE. Then I recreated one I’d made for an abortion-rights march some time ago: VENGEFUL GODDESS SMITE THEM, with flanking lightning bolts.11 When I had chosen where to pin them, he asked me if I wanted to contribute to the mural he was working on, on the wall— maybe he approved of my penwomanship— and I took inspiration from my countryperson and wrote TOITŪ TE TIRITI. (I was sad that I’d missed the hikoi at home.) When we parted we hugged, a proper embrace, for long enough that I could feel his heart beating against mine, and I thought that I hadn’t been hugged that way for a long time, not by a stranger, not even by very many friends. I’ve become a fortress, not liking to be touched— but this was a good hug.

When I left the arcades and went outside I saw that night had indeed fallen. It felt just like when you leave the movie theatre into the surprise of dark: the arcades were their own self-contained world, and time had passed while I dallied there. Things felt edgy. I was a stranger in a strange land, far from home. I felt suddenly burdened by all the stuff I was carrying. People called things out to me from the shadows. “Hey, pretty…” I realised it had been a number of years since I’d experienced this flavour of attention, gendered, and read as a mark— I aged out of it some time ago; but there were other signifiers at play here.12 I was glad I was wearing my usual uniform— jeans, jacket, and boots— instead of the dress I’d briefly considered. I drew my invisibility cloak around me, walking briskly, not making eye contact. I didn’t want to walk along staring at my phone like an obvious n00b, so I walked for some time before I realised that I was going in the wrong direction— the old 180° backwards magnetism. I asked directions to the station, then tailed some tourists back, following at the edge of their pairing as if I was one of them. While I was waiting on the platform a woman with a crazed vibe approached me, putting her hand to her stomach and saying she was three months pregnant and needed ten pounds for the shelter, and… She was an obvious crackhead, but I gave her my postcard change and she said Bless you Madam, you’re an angel. There were two little boys on the wooden seat beside me, brothers: the big one punched the little one in the arm, and the little one cried, and then the train came.

The next day was a Monday, and Elliot (the sweet-natured window guy) was happy to hear that I’d visited the other side of the river. He has a Sound System, which he talks about as if it were a job, or a spouse (he told me his day off wouldn’t really be a day off, because he would work on the Sound System, and he also told me that the components of it take up most of the space in his small flat) so I guess he spends time in Brixton. He said next time I come over he’ll take me to a party, and I said I’m keen as mustard.

Love,

Rose

Tourists go to Queenstown and Wanaka, but I’ve never gone that far South. (Conversely, I go to Highgate and Bunhill, but a lot of Londoners never have.)

Named for the cross, one of twelve, that Edward I (Longshanks, the Hammer of the Scots) erected for his dead wife Eleanor of Castile in the 1290s; one cross at every place they stopped for the night as they processed South to Westminster to bury her. I also saw (fleetingly, from the bus window) the cross at Hardingstone in Northampton, one of the three that survive in their original form.

While I was in England I was very conscious of the finder’s triangle of time :: money :: distance / difficulty. I usually have small money, but abundant time— which also equals ability to travel further, as well as to hunt longer. In London I had more money than usual, but far less time, which made it harder to get to the out-of-the-way places. The closer to the centre, the more London felt barren of fertile chance, like a chicken picked clean; I sensed that the further out one went, the better the pickings would be.) Because any kind of thoroughness (let alone completism!) was impossible, I reverted to dumb instinct and luck, the Zen bones of finding. No think! Find!

Later on I thought I should also have looked up my Grandfather’s Grandfather’s village, but I didn’t think of that at the time.

It made me think of Agnes Varda’s film The Gleaners and I: in fact, I had bought a sepia postcard of Millet’s Les Glaneuses at the postcard fair, from the retired Scottish psychologist.

I could only find books, not clothes. For instance, on my way South, I had found a first-edition Rosemary Sutcliff in a charity shop for £3.

The prophet

From his mid-afternoon full English breakfast. He was on a date— very obviously a morning-after (or rather, afternoon-after) date. He was a big man, and I liked his expansive confident energy; there was something Kingly about it, as if he were sitting in his firelit hall calling for more mead.

I was always getting mistaken for an Australian, to be fair

Sometimes not: public transport in particular carried a taboo on conversation, I think because of so many bodies in close proximity. I did have a few good public transport yarns, though. There was the woman with whom I rode the train to Milton Keynes, talking all the way. While we were standing in the queue waiting for the gate to open, dumb herd animals, I had asked the four nearest people “Is this the train to Milton Keynes?” They all stared at me blankly. She was the only one to respond. (Later she said she thought I was addressing someone I knew, then realised I wasn’t.) At the very end of our shared journey, after I had tried to get her to come to Eliza’s gig with me and she had said she had to go home and cook dinner, I asked her what her job was, and she said she was a diplomat.

Also there was the American woman who I navigated the Tube with when we were both confused by our phones. (The Tube station turned out to be at the far end of the very long train platform, down an elevator and through three sets of gates.) She had a Boston accent and a baseball cap. She told me she was in her seventies, and that she had leukaemia. In spite of that, she was in London to run a high-powered contract, and as we rode the Tube she told me a convoluted story about some Machiavellian karma-plot whereby one businessguy took slow revenge on another businessguy. (Salaryman Shakespeare?)

You can see the original placard near the bottom of this post:

Beneath the Pavement, the Beach

When ugliness, poor design, & stupid waste are forced upon you, turn Luddite, throw your shoe in the works, retaliate. Smash the symbols of the Empire in the name of nothing but the heart’s longing for grace.

One guy, standing in a little cluster, called out “Hey— journalist!”

Which tickled me.

I admire your persistence and your communicative style. I am envious and a bit astonished at how you are able to communicate with these spiky Southerners - very WalterBenjaminesque in the arcades, incorporating top level flaneurship

Thanks Rosie, as an ex-Londoner I'm enjoying your view of the place and its life (I say ex-, it's been 8 long years, but then longer I don't live there, the more I realise how much it's part of me...)

The Stone Tarot sounds really interesting, but I can't find more than a mention of it in your other writings (it's not so easy to search for specific stuff within substacks, I find) - if you've written more about could you point me towards it?