This piece contains a lot of images: it will get cropped, so click through from email and read it on Substack.

Robert Macfarlane: “We are part mineral beings too— our teeth are reefs, our bones are stones— and there is a geology of the body as well as of the land. It is mineralization— the ability to convert calcium into bone— that allows us to walk upright, to be vertebrate, to fashion the skulls that shield our brains.”

M. John Harrison: “Cheese sandwich, the gritstone madeleine.”

I saw this the other morning at Breaker Bay:

It’s the packaging from a seagull’s breakfast. Black-back gulls drop sea-snails onto rocks from on high to smash them open. This one was Cantharidus opalis, the beautiful Opal top shell. If what my little shell book1 says is accurate, this was one of the first species in New Zealand to be given a Latin binomial, on Cook’s voyage. Also visible on the rocks: the edible seaweeds karengo2 and sea lettuce, and some small barnacles, which I guess are the ‘modest barnacle,’ tio piripiri / Austrominius modestus. If so, they are the barnacle that has colonised Europe, out-competing Britain’s native barnacles in places.3 (Perils of shipping.)

Kat and I both secretly photographed each other taking photos.

My photo of her:

Her photo of me:

We followed a friendly grey terrier up a steep sand-path. (I had patted the little dog. Its fur was very soft, as if it had just been washed.) From the clifftop, the harbour was mercury.

I had thought to start this piece by quoting something I read recently about David Wojnarowicz, and how he saw rooms everywhere; he had sometimes been homeless, and the room was a recurrent motif for him. I searched through the places I thought I might have seen it, the three books I’ve recently read. Like Love by Maggie Nelson; The Naked Don’t Fear the Water by Mattheiu Aikins; and Wish I Was Here by M. John Harrison. As I searched each of these books (back to front, as for some reason that’s easier)4 I had high hopes. Maybe it was in Nelson’s interview with Carolee Schneeman, which touches on precarity? Maybe it was in the part in Aikins about the refugee camp on Lesbos, or the part about the Anarchist enclave Exarchia? Maybe it was in Harrison’s miscellany (unlikely but possible)? Each of these books was densely mycelial; each offered dozens of rabbit-holes, and I couldn’t help going down some of them along the way. I noted down Björk from the Maggie Nelson book:

“can we all please invent a continuity?

perhaps i can offer some suggestion

hidden in the icelander’s relationship with

nature . . . would that interest you?”5

As I searched these texts for the long name-word Wojnarowicz— a word that would surely stand out from the page’s field— I thought about the poem Bill Manhire wrote about how New Zealanders scan a text for the Z,6 and how I personally scan for the mountainous W of my own surname. Searching for we, searching for me, constant, half-unconscious. The quote could have been in any of these works because they all touch on home, a universal human preoccupation; they touch on a room of one’s own. It wasn’t, though.

When I searched ‘Wojnarowicz home’ online, I found this piece: Hannah Gold - David Wojnarowicz’s Home in the City.

None of these were what I was looking for, the mystery person quoting Wojnarowicz’s preoccupation with finding rooms. Maybe I had misremembered, or maybe it was somewhere here in the forest of Substack that I’d read it, in which case there was little hope of finding it again. Instead of the quote about Wojnarowicz searching, then, you get the story of my search for the search. As David Byrne sings in This Must Be the Place,7 I’m just an animal, looking for a home.

A new thing in the city is people in bed by the side of the footpath. Mattress, blankets, sometimes shoes lined up, a jacket hung on a pole. Homelessness makes people nocturnal, I guess— safer to sleep in the day. When I pass someone in bed it seems rude to stare. They have made a little piece of the city into a room for themselves.

Friday night I’d been at Sasha and Achille’s postering show,8 where I made some posters by writing on paper with Posca and Vivid.9 It was fun to HAND MAKE THING instead of just BRAIN THINK THING, and I saw that all my years of calligraphy practice were still there, living inside my right hand. Afterwards I dodged around a guy who was yelling at thin air in the Left Bank, and escaped town before things got too Wellington-Babylon.

Walking home around the Coast it was still and not too freezing, although there was the massive ring around the almost-full Moon that means ice crystals in the atmosphere. In the big dark carpark there was a van, emanating loud electric guitar. It was parked at the edge of the carpark nearest to the sea, and I couldn’t work out if it was a recording or if there was someone sitting in the back with a guitar and an amp, having a private shred: van as portable rock-garage. I passed by at a distance, and just as I got to the corner the riffs resolved themselves into the Star-Spangled Banner—10 Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock. Solve et Coagula.

On Sunday, returning from Paekākāriki, we turned off at Pukerua Bay on a whim. The road is a steep and narrow diagonal that cuts down the cliff face. Down at sea level there’s a little village, a row of boujee, architectural-looking houses tucked into the foot of the hill. (Climate change has changed the reading of such dwellings from aspirational to vulnerable; asset to albatross.)

We got out of the car and walked past some kids hot-boxing, their vehicle spilling doof and weed, past the tall pou (carved from a large tree trunk, I reckon— it has a tapering, organic form), and onto the track, made of chunky gravel. After a while we both started to suspect it was a new way, a path we’d never walked before. (I knew I’d been there before, but maybe not walked far?)

We soon came to a stone gateway, a hole through a rock marked on the phone’s map as Te Ana o Hau.11 It was so distinctive a landmark that we knew we’d never been there before. It was the kind of power-place that draws stories to itself. (Later, describing it to Amy, I said it was a giant hagstone on its side.) From a distance I could see people dressed in blue, hanging around the rock. I didn’t take a picture, because I didn’t want them in my shot. (Also, I know from experience that magickal places are hard to photograph: it’s like they resist reduction to an image.) We walked through the rock arch, which carried its own microclimate— a chill, and water dripping from a certain point of the underside of the arch. (Probably there were life-forms resident there— glow-worms, for one.) The sooty overhang on the other side had marks of usage: the remains of fires, bits of wood for seats, and graffiti on the stone, arcane signs painted in white. The three blue people were there, and the woman was sitting on the stones pulling on shoes with red rubber soles— rock-climbing shoes. We didn’t talk. They were about their business and we were about ours.

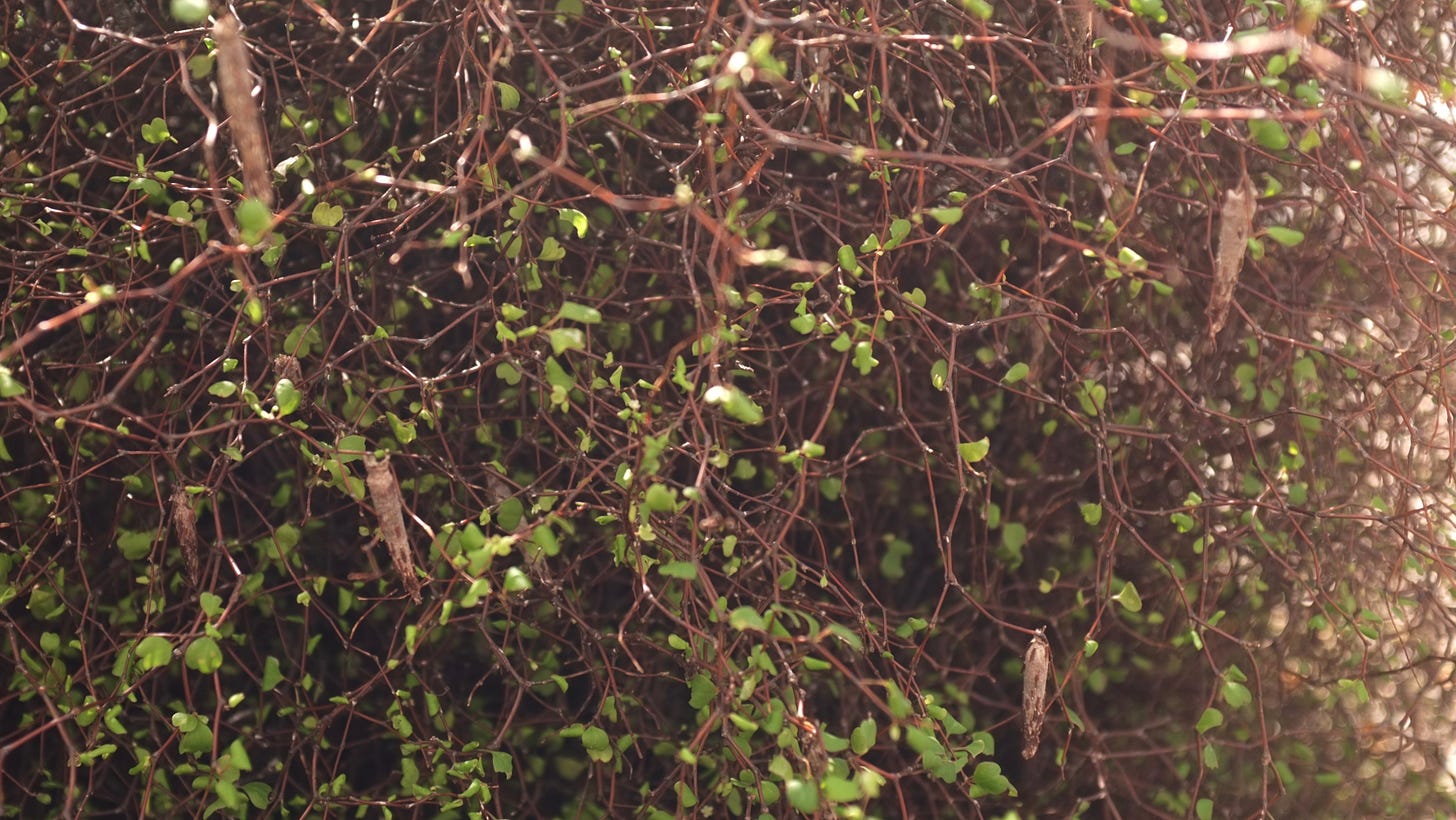

On the other side of the stone doorway, the path carried us onwards, changing form as it went, through bushes and through briars. At the track level, pohuehue / Muehlenbeckia dominated. It’s a moa-proof plant, with small leaves inside a twiggy mass, unrewarding to browse:

(Many plants of the Aotearovian bush are adapted against moa-browsing. Witness the horoeka / lancewood, that has long, tough, spiky leaves until it gets above moa-height, then transforms its form: this adaptation, different juvenile and adult forms, is called heteroblasty.) The pohuehue bushes and the small manuka were topiaried by the wind into rounded, boulderish forms. Up on the hill, karaka groves were similarly bonsai’d by the wind. No human sculptor can rival nature, which has all the time in the world to fit things to their environment.

Here’s me, walking somewhere novel. It didn’t take me long to notice that the environment was almost entirely natural. There were very few human-things to be seen. The ubiquitous pest-traps.

A green and gold DOC sign, announcing that we were entering a Scientific Reserve.

Kev: “It’s probably a specialised environment for something.”

Me (guessing): “Skinks.”12

A metal gate: high and low bars across a rock gap, wreathed with rusting chains. Kev said he couldn’t work out what it was for; I said cattle.

But aside from these bits of ancient and modern infrastructure, there was virtually no rubbish— no jetsam— just wildness. I could feel that this place was teeming with invisible life, perfectly adapted. I started thinking about how a beach is an untameable place. That’s why I like it so much. That’s why it feels ancient. The place where the sea’s edge meets the land cannot be controlled: it’s innately anarchic. The sea can’t be parcelled out and modified like the land can. The sea is the biggest wild animal there is.

Every beach is a multi-layered portal of story, infinite openings offering themselves for investigation and consideration. One sees different stories with new eyes. Driftwood, for instance: the driftwood here was different from at Makara, our previous Sunday walk. At Makara the wood was gnarly and piled up, whereas at Pukerua Bay the logs were mostly long and straight, aligned parallel to the shoreline, laid alongside each other like a box of matches. At certain places, the logs far out in the rockpools were stained a teaish colour, so they looked uncannily like animals— seals or walrus, tumbled together in a pile.

At the landward side of the drift, meanwhile, the driftwood had lain long enough to disintegrate and become host to mosses, lichens, and other detritivorous plants. The story, I could see, was that the sea laid the wood way up high then never took it away again, and the logs that had been sea-stuff were slowly rotting back into earth-stuff, becoming food.

I saw a long log hosting a whole ecosystem— it was suspended in mid-air between two boulders, its hollowing trunk full of mosses and lichens13— and tried to photograph it, but couldn’t. Either it was that magick thing again, or, thinking about it now, it could have been because I was using Kev’s phone instead of my camera. (I shoot in a long, cinematic aspect, 16:9, whereas Kev’s phone shoots close to square, 4:3. I couldn’t make the long trunk-form work in a short framing. Also, I’ve always shot manually, but the phone makes all the decisions for you. I was working out that it takes pretty good photos in daylight, but it doesn’t like the night and light and the half light,14 all the edge-lights I most favour; and I like a dark, velvety image, whereas the phone thinks everything should be bright— in imitation of its own glow, maybe). All this time I was trying to shoot the log, Kev was walking ahead, so I had to give up and catch up. Anyway, I thought, I can TELL about it. What was happening was that thing where a decaying tree reveals its younger self inside itself, a more slender trunk and branches suspended at its core; I guess it’s heartwood.

Trunks, roots, branches, twigs, vines, cones, nuts, scraps. Some of the driftwood has flat, machine-cut ends, from human-husbanded places, farms, gardens. Some is out of the bush, fallen, carried by rivers to the sea, then by prevailing currents down the coast. You can also mostly make a guess what tree it was, if you know anything about trees. The point is that the driftwood is a whole universe of information, stories of origins and processes implicit in each unique piece of it. (And if the driftwood wasn’t here, you could look at the rocks the same way, leaping into deep time: though I am fascinated by stone, I don’t know much geology, but sometimes you can SEE what happened to the rock. It got laid down in layers like filo or Damascus, then it got squished up sideways, for instance.)

Another thing I was thinking about is that most driftwood is small enough to be carried around by a single person. There are logs too big to move, of course, but even quite big bits can be dragged from place to place. This makes them a material for play, and even adults play the ancient game of making houses:

These tiny houses are everywhere on the coast, anywhere there’s driftwood. I don’t tend to photograph them, I think because they are other people’s work. They’re a creative intervention that consists of rearranging found materials into a temporary form. (Temporary, but they can stand for months or years.) This is a type of sculpture that pleases me, Goldsworthyesque, a harmonious / purposeful rearrangement of found objects. It seems close to the ancient essence of art.

My witch-friend Anna has a campaign in the U.K. to try to get people to stop tying polyester ribbons and suchlike non-biodegradable tat beside holy wells and sacred sites. In the old days, you’d tear a strip off your petticoat— a clootie15— and tie it on the tree as a petition to the genius loci. People now tie ribbons and rags made of synthetic fibre that don’t beautifully rot back to nothing like linen, wool, or cotton used to. (I think also of the bright fake flowers piled on graves. I often find fake flowers on the beach— they’re indestructible.) Magick is knowing what something is made of— where it comes from— seeing what its life ahead will be. There’s great beauty in rot, wear, and decay: immortality is what makes something rubbish.

To sing or dance to a place is the lightest way, leaving only an energetic trace. Or to walk it: walking a path is remaking the path. Robert Macfarlane says: “Paths are the habits of a landscape. They are acts of consensual making. It's hard to create a footpath on your own...

Paths are consensual, too, because without common care and common practice they disappear: overgrown by vegetation, ploughed up or built over… Like sea channels that require regular dredging to stay open, paths NEED walking.”

I read that in the Arctic there’s a cultural prohibition on moving stones, because they are landmarks others use as navigation points in a subtle landscape. Jay Griffiths: “One of the most important of these [rules] was not to take anything away from the land, no rock, no fossil, no stone, nothing…. One young Inuk man told me it was ‘disrespectful’ to change the land. ‘Someone who was respectful of the land would not even move a rock unless he needs to use it.’ It was also a practical rule, because every feature in the landscape was a map: someone might have memorised a particular route, taking directions from the relationship of the prevailing wind between two rocks. If another person moved one of the rocks, the first man, returning on the route he had learned, might fatally lose his way.”

Closer to home, people stacking or balancing stones (InstaZen) can interfere with stream life, or rockpool life. But also, we humans are part of things, and we are an animal that likes to play. In the bush, where I grew up, we made huts often. This seems an innate, universal behavioural stage, much like the need to play with fire, to get food and cook it. There is something hearty in this house-making game: do it yourself.

What is a house? In the case of a driftwood hut, it is an enclosed space you can climb inside.16 The wall-roof of it makes some shade, but it doesn’t keep the rain out. It’s a fantasy-house, summoning the story of a shore-dweller. The beach-combing hermit in Local Hero, the lighthouse-keeper in Moominpappa at Sea, Robinson Crusoe. The fishermen at Makara, the whalers on Kapiti: they lived in tiny shacks on the shore. A house is— at minimum— shelter from the storm. (Walls, roof, food, fire, bed.) My own house is a kind of iteration, too. My friend Linda, who lived in my house at the turn of the century, in the days before the Marine Reserve, told me how she used to go diving for dinner, crayfish or kina, and how she kept the house warm by burning driftwood on the open fire.

I had already forgotten the last chapter of Bring Up the Bodies, until

’s Footnotes and Tangents post reminded me this morning.17Context: Anne Boleyn has just been beheaded.

[Thomas Wriothesley:] “I smell burning buildings,” he says. “Fallen towers. Indeed there is nothing but ash. Wreckage.”

[Thomas Cromwell:] “But it’s useful wreckage, isn’t it? Wreckage can be fashioned into all sorts of things: ask any dweller on the sea shore.”

We kept on walking. To get to the point. It was almost evening now. I could smell the daphne sprig I’d broken off the bush by Osha’s door and tucked in my lapel. Its heavy perfume was non-native but delicious.

At the headland, the landscape became truly sublime. Huge chunks of rock, each with its own distinct character. Each would be named, multiply named, layers of story I didn’t know. An infinitely deep kind of place. The light was changing fast, and the phone was low on battery, and the view was too BIG to hold in a small box— nevertheless, I snapped one shot.

There wasn’t time to linger long. We had come pretty far, on a rough path, and Kev had city shoes on.18 We had to turn back and walk fast, to beat the night home, looking at the stones underfoot so as not to trip. The way back always feels shorter than the way out. Waymarkers noted on the way out arise faithfully in reverse order, THIS bush, THAT kink in the path, the place where I’d kicked pebbles over the dogshit. I got warm, took my coat off, then my hat. We covered the bays. I crossed over the drift to the beach so I could look at driftwood as I walked, but when I slipped and knocked my knee, I went back to the path again. The pou came in sight as it was getting properly dark, and I knew we’d make it. When we rounded the corner to the carpark the perfectly full moon was rising, hanging against the land’s dark breast like a glowing pearl. I know that the moon’s beauty is the most unphotographable of all things. I didn’t think it was worth trying to shoot—Don’t worry about it, I said, it’s impossible— but Kev did. He took this photo:

As I finished the first draft of this piece, I read this beautiful meditation on different kinds of walks from

: Uncivil Savant - The Walk That Never Ends. Caro and I had this thing happening for a while, a kind of morphic-resonance twinning, where we would find we had written about the same thing. This is that again: I guess walking is walking. Wherever you are, the way is the way.Native Shells of New Zealand by R. K. Dell

I ate some, it was good

London, I hear, is full of harakeke, or as they call it, Phormium. This reverse-colonisation reminds me of the Gustave Doré engraving of Macaulay’s New Zealander: Public Domain Review - Gustave Doré’s The New Zealander (1872). “Who was this New Zealander? Largely forgotten today, he was so omnipresent in the 1860s as to be labeled cliché. An 1865 issue of Punch magazine, for example— explored by both David Skilton and David Runciman— proposed banning the use of ‘certain persons, objects and things, part of the stock-in-trade of sundry literary chapmen’. At the head of this list we find ‘Macaulay’s New Zealander’: ‘The retirement of this veteran is indispensable. He can no longer be suffered to impede the traffic over London Bridge. Much wanted at the present time in his own country. May return when London is in ruins.”

There’s also the creakily humorous poem by [NZ poet] R.A.K. Mason that begins (from memory) “This, quoth the Eskimo Master, was London in English times…”

However, it doesn’t exist on the Internet.

Maybe a handedness thing, or maybe it reduces the likelihood of getting sucked into the narrative?

Björk’s text in this interview is all centre-aligned, but Substack doesn’t offer that spacing choice.

It’s called Zoetropes— read it here: https://www.timjonesbooks.co.nz/2010/07/29/nz-poetry-day-zoetropes-by-bill-manhire/

I was going to link to the only video I’d seen: the Stop Making Sense version, with the standing lamp. But this time the algorithm took me to the official video, which shows … Well, just watch it and you’ll see. I note that the song was recorded in 1982, when I was 2 /3 years old, not much older than those babies in the video.

The Internet says it was the last song off Talking Heads’ last album, Speaking in Tongues. The band swapped instruments, making the music very simple, or as the title has it, Naïve. Byrne: “That's a love song made up almost completely of non sequiturs, phrases that may have a strong emotional resonance but don't have any narrative qualities. It's a real honest kind of love song.”

iMpOrTanT iNfOrMaTiOn at Enjoy

I wished badly I had my old journal volume to mine for chunks of witticism, which I tend to write in capital letters for ease of picking out (e.g. THE REAL WORLD MISSES YOU)— but I’ve recently switched volumes, and only had five pages (and memory) to draw from.

See also: this video of Wulf Hein that I sent to Finn last week when we were talking about making flutes out of bird bones. This is from Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams, and the flute Hein plays is made from a vulture’s radius.

More about Te Ana o Hau here: Michael O'Leary - The Ballad of the Triple Track

Yep— New Zealand grass skink Oligosoma polychroma, on page 2 of iNaturalist: https://www.inaturalist.org/places/pukerua-bay-predator-free-project-scientific-reserve#page=2

‘Cloth’ in Scots

The homeless sleeper’s ‘room’ is an island made of bed, It doesn’t have walls, and that feels so vulnerable. Walls are a delineation, a barrier between inside and outside.

We are long-reading Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy.

The moral of the story: Be Prepared.

‘The sea is the biggest wild animal there is.’ Never in my life have I loved a thought more.

."The packaging from a seagull’s breakfast." 💯