“No, it can’t be right. That’s chalk country over that way,’ said Miss Tick. ‘You can’t grow a good witch on chalk. The stuff’s barely harder than clay. You need good hard rock to grow a witch, believe me.’ Miss Tick shook her head, sending raindrops flying. ‘But my elbows are generally very reliable.”

Terry Pratchett, The Wee Free Men1

From time to time the sea or a river offers me a phone.

I remember when I first began to notice people on the bus staring fixedly into their personal black mirrors. It was bloody weird. Were they … enchanted, somehow? (This was some years ago, when the mass public techifying was still novel.) I was bored; nobody would catch my eye any more. Thus deprived of interaction and forced to entertain myself by pondering, I had the bright idea of a cargo-cult phone. (Briefly, the way a cargo cult works is that people come to believe that if they emulate the behaviours and forms of the newcomers who are so rich in stuff, they will in turn be bestowed with the bounty the newcomers have magical access to; i.e. build an airport out of bamboo, wait for the planes to arrive.) It would be possible, I thought, to carve a scale model of a smartphone out of some shiny black stone— obsidian would do, with its shades of Mayan sacrifice-knife— and sit there on the bus running my finger over its glassy surface, tapping it with my thumbs, pretending to be important; then sit back and wait for the boxes to arrive at my door.2 Then I saw that the joke would be too subtle. Nobody would notice any difference between my stone scrying-tablet and the portable portals they were so entranced by.

Then I started thinking that maybe the idea itself was the work, and all I had to do was tell it to people. Conceptual, innit?3 (This was a truly lazy perspective based on knowing how many fucking hours it takes to carve a stone, and knowing that I lack the requisite mathematical brain + inhuman patience + obsessive exactitude combo to make something exactly like something else.) Anyway, after some time polishing this idea, I realised that the genius stonecarver Joe Sheehan had already made something very like what I was imagining.4

I saw once, in the exhibition Aztecs: Conquest and Glory at Te Papa, a knapped obsidian knife with a staring eye and bared teeth: a tecpatl, a naked blade for the cutting out of human hearts. It was a genuinely terrifying artefact, emanating darkness, that I felt shouldn’t be on display. There’s a parlour game— if you could spend a day at any time and place in history, where and when would you choose? (Caveats: your safety is assured and people treat you as one of them.) I went around asking people this question for a while. For instance, it was a good hitch-hiking ice-breaker. Most people chose somewhen boring like New York in the 1960s or Paris in the 1900s— though I remember one driver who picked his era of expertise. (Was it Ancient Greece? Edo-Period Japan? All I remember was that he immediately had a ready answer.) My go-to was always the Palaeolithic. (Wouldn’t you want to go as far back as it’s possible to go? Imagine the questions you could answer! Imagine the bogus evolutionary biologists you could once and for all debunk with your first-hand observations!) My second pick, though, was to wander through one of those ancient Mayan or Aztec jungle cities. (Fine words, but I’d probably faint. That’s what happens when I see blood. I’d be useless in battle for the same reason.)

While I was in London I consented to possess a smartphone for the first time in my life. I had to, for safety reasons, mostly to do with wayfinding in a massive unfamiliar city. Both my Dad and my sister had been hassling me for years to cease this dumbphone nonsense and join the modern world. My Dad, who once called all cellphones cancerphones, now shows me how the device in his pocket contains all his favourite early music, accessible at a touch. Neat, eh? Pretty cool, eh? (I’ve stopped arguing back. I know he’s coming from a place of love, like those who want to save others’ souls from Hell.) I gave in and my Dad sent me his old phone in a cardboard box smelling of woodsmoke. At first I could hardly bring myself to touch the thing. It was a capitulation, the crossing of a line I’d drawn in the sand a long time ago. And, like the tecpatl, the phone emanated juju I didn’t want to mess with.

The depressing fact of the matter is that virtually none of us are immune to tech’s siren song. These days we’re all lab rats for the meagre pellets of dopamine, compulsively pushing the lever with our little paws. Part of the reason I’ve avoided the smartphone for so long is that I’m an addict; I’m intimately familiar with the horror-state of hating what you’re doing whilst simultaneously being unable to stop. It’s very difficult to [take addictive drug] daily for a month then just knock it off. (And I’m a grown adult— I’ve not been weaned onto the device as a baby.) The power of the smartphone to swiftly rearrange one’s neurons does feel like sinister magic to me. It feels like enslavement, because it is.

wrote a Note yesterday comparing phone addiction to cigarettes: “Many of us would like to escape, and yet - unlike nicotine - the digital world is a social addiction. It’s not only foisted at us by all the dealers - the Big Tech companies that benefit from it - but also by all the other addicts. You can try to put it down, and not light up, but everyone around you will pick it back up and hold out their lighters for you.”On the banks of the Thames it took me a long time to get my eye in,5 because I couldn’t stop seeing the flints underfoot as human-made forms. Goddesses, bones, animals, body parts. The other mudlarks were after the precious and rare— gold, jewels, antiquities, curiosities— and I was interested in those too; but to me the substrate itself was fascinatingly alive. The flints in particular seemed expressive, almost sentient. The Thames-bank flints are grey-white or golden-brown lumps ranging from marble-sized to fist-sized, often with the rind rubbed off in places to show the dark-grey interior.6 (Flints do come bigger in the wild— apple-box-sized, horse-head-sized, etc.: huge nuggety beasts that farmers dig out of their fields.)

In the world before metal, flint was the stuff of life. Horn and stone; the bounce of antler, the brittleness of flint. Antler was used to dig flint from the chalk. In the Early Neolithic, 4000 - 3500 years ago, flint was mined from the Downs using antler picks to hew into the sides of deep shafts. The diggings got deeper over time: initially in pits, then shafts sunk straight down to access buried seams of flint, then undercut like a bell, then tunnelling out sideways from the main shaft, following the horizontal seams. (For instance at Cissbury, where the skeleton of a 25-year-old woman was found buried in a mine shaft: she is thought to be a miner who died in a tunnel collapse some 3900 years ago.)

I also think of Ötzi’s toolkit. He had a pencil-shaped tool with its point made of inset antler— a retoucher for sharpening up his chert tools by chipping tiny flakes off the cutting edge. Here’s a reconstruction of its making:7

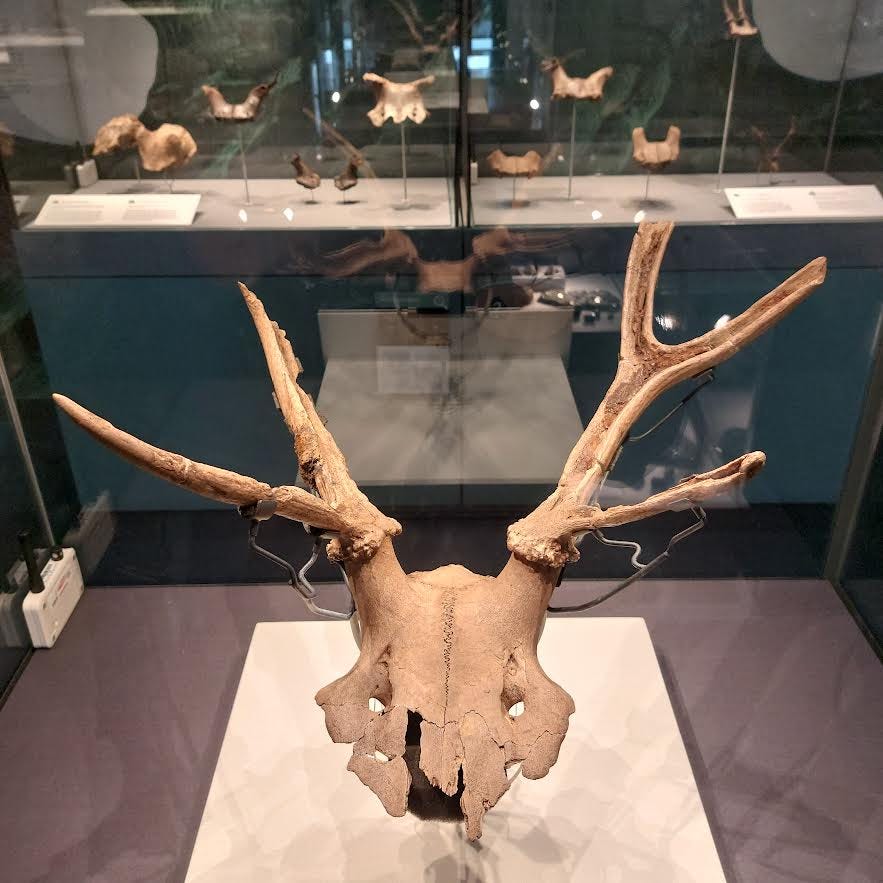

At the York Museum with Eliza I saw the antler headdresses from Star Carr. I stepped inside the door, and there they were. It was surreal to see them in the flesh— these potent ancient objects I had studied for so long.

It is thought these antler frontlets were worn, possibly as masks or head-dresses: some of them have holes, made with stone drills. The antler dance is still danced to this day in Britain.8 The Abbots Bromley Horn Dance, in Staffordshire, uses reindeer antlers that have been carbon-dated to the 1100s; one theory goes that they were brought from Scandinavia. The dance is danced in September, at the end of Summer, and the antlers are kept in the Parish Church betweentimes.

The deer is a complicatedly magical animal; sacred in the land of my Fathers, a pest species in the land of my birth. I like to eat them, and I like to invoke them. My antlers (you can see them in my profile photo) are made of driftwood and leather. I constructed the antler head-dress for a public Midwinter ritual some years ago. The trickiest thing was finding a well-matched pair of sticks. Driftwood is far lighter than true antler, but my antlers still have form— they take up airspace. Wearing antlers changes the way you hold your head. Something of the stag’s proud bearing takes hold of your neck. (For safety’s sake, I have a pair of very tall platform shoes with wooden heels that I wear to elevate my antlers above most people’s eye-height; also, they make a hoof-like tip-tap.) Like the time I went to a Space-themed dress-up party wearing a metres-wide radius of balloon-tentacles, wearing antlers is an exercise in interspecies consciousness-raising. Adults are baffled or amused, children are half-terrified, half-delighted. Once when I was wearing the antlers in town a drunk man squared off to me, scraping his foot on the pavement and snorting through his nose.

The Stone Age is not just theoretical to me. I come from a Stone Age place. Like many of my countryfolk, I wear a stone around my neck. It was a gift from my friend Ben the stonecarver. He said he had realised that if he only sold his work and never gave it away, it would all end up in the hands of strangers once he was dead. I remember how it felt to put it on for the first time: the weight, the shocking coldness, the stoneness of the piece spoke to my body, saying it had been a long time since I wore stone.

Obsidian and flint are both used for blade-making, and they are both made of silica, but they are opposite in their formation. One is born of fire and one of water. Obsidian is igneous— quick-set molten lava. Flint is more complicated. Nobody really knows how, but the remains of tiny prehistoric marine animals provide the silica that coalesces and grows slowly within the belly of the chalk into the nodules of flint.9 That is, flint is sedimentary; and it’s porous, despite its ability to be knapped into a cutting edge— hence the flints out of the London clay are yellow, the ones from the Downlands (previously used for construction infill on the Thames) are white. Flint is bone-like, and stone is the earth’s bone, that which endures when the flesh falls away.10

Pounamu / greenstone is not igneous like obsidian, nor is it sedimentary like flint. It’s metamorphic: formed through tremendous heat and pressure deep inside the earth, its fibres compressed and felted into a dense stone weave. Like flint, though, it has a rind— an inner and an outer. Both flint and pounamu come discrete, fruit-like, planetary. Maybe that’s also what makes them seem alive: they are bodies that move, tumbling in river or wave, or borne on the glacier’s back.

To the human-time eye, stone is an immortal material. It can weather countless millennia in earth or water, the elements of its origin. (It doesn’t like fire much, but to some extent it can weather that too.) The things that alter stone are shattering or abrasion. Those are the ways stone acts on stone in the wild— one fast, one slow— and those are also the techniques we humans employ to change stone. Splitting, knapping, grinding, rubbing. Pounamu, a very hard stone, was traditionally worked stone on stone.11 Down in the creek for months, shaping an arm, a leg, an eye socket, with tens of thousands of strokes. (Due to this laboriousness, the natural form of the stone influences traditional design.) When worn against the body, stone and skin speak. Over time, some ancient taonga12 have had their contours smoothed by multiple generations of bodies. Some have suspension holes that have been worn through to the edge, rubbed away by the cord over centuries of wear. Skin after subtle skin of the stone has been slowly revealed by means of a steady, oiled caress. The beauty of the surface of such stones can’t be described.

(Pounamu, of course, as well as being an adornment, is toki and mere / chisel and weapon; for biting into wood, for the killing-blow. Stone that can take and hold an edge— ultimate usefulness. Beauty and lethality go hand in hand.)

To work too fast is to misunderstand stone. Stone is time. There’s a famous whakataukī: Whāia te iti kahurangi, ki te tuohu koe, me he maunga teitei. (Seek the treasure you value most dearly; if you bow your head, let it be to a lofty mountain.) This is often interpreted metaphorically— one should strive for greatness— but I think it can be taken literally as well. The dominant mountain of the landscape I inhabit (as I said in my last post) is Tapuae-o-Uenuku, which has stood for 100 million years, since it was an infant volcano near the outer rim of Gondwanaland. That’s what geological time means. I’m not a geologist’s bootlace, but I find it comforting to think about.

In England, I loved the ancient buildings built in flint. They were numerous in London, Brighton, and Kent. Often the visible face of the stone had been split— knapped— to make a flat or flattish surface, revealing the interior of the flint: dark grey speckled, starred, or clouded with light grey. I’d lay my palm against these Winter-cold stone galaxies and try to absorb deep time.

Kev says that the economics of building with flint are to do with the relative cost of labour and materials. Flint as a building material is free— it lies around, you pick it up— but costly in terms of labour, as it is slow to lay, due to its uneven form. Brick is historically costly to produce, but quick and easy to lay.13 The trend away from flint and towards brick reflects a shift to lower manufacturing costs (i.e. the industrialisation of brick-making) and higher labour costs.

He tells me the names of some flint-building methods:

Coursed rubble: unaltered or mostly unaltered flints laid in horizontal rows like bricks, with mortar filling any gaps. (This is the most common method, because cheapest; used for anything utilitarian.)

Snail-creep: one face of the flint is knapped but the shape is otherwise unaltered (as in the photo of St Mary of Charity above). The term refers to the meandering shape of the mortar joints between the stones. Snail-creep is time-consuming because it’s a giant jigsaw puzzle, much like a dry stone wall14— the mason is continually fitting stones against other stones for the strongest construction.

Squared / Ashlar: the flint is knapped to give a square edge on all sides and laid very closely. (This is extremely skilled work, time-consuming for the mason, and thus very expensive and prestigious.)15

This Peter Bellamy song— a Rudyard Kipling poem set to music— takes the perspective of Puck of Pook’s Hill, a creature who has been there since the beginning and witnessed all that has passed.16

And see you marks that show and fade,

Like shadows on the Downs?

O they are the lines the Flint Men made,

To guard their wondrous towns…

It could just as easily be the perspective of a stone: Little moth, little moth, you who live but a day, I will briefly abide with you.

Somehow this post was sparked by sitting next to Sammy at the Bunker, the Monday after the Auckland Folk Festival. I had my black leather satchel and he had his weathered-khaki canvas one, and they sat side by side on the low table before us, leaning against each other. As we listened to the floor-singers, he unbuckled his bag’s straps and opened it.17 From one of its boxy compartments he selected a notebook and a pen, and began to write. The notebook was brown, with an inbuilt elastic to hold it shut, and it had Notes handwritten on the cover, and lined pages. I could see a doodle of a smiley-face sun on the facing page.18 In all these particulars, it was not like any book of mine. In short, it was an alternate cosmology; the glimpse into Sammy’s bag felt like a peep into a parallel universe. After a bit he opened his other bag, a cubish black hard-case suspended from sturdy webbing straps. There was only one thing in there, nestled into careful padding. My brain saw the black wood and pleated leather of it and thought camera— but after a moment I saw that it was not for images, it was for sound— it was a concertina. A small portable instrument, played on the knee; carried guarded against knocks in its mollusc-like shell.

There is something Ötziesque about this carrying-of-all, like a pedlar with pack on back; immediate access to a kit encompassing not only the tools but the meta-tools, the tools to tinker with the tools.19 Mend and make do. It made me remember again how my initial concept of Wizarding was to do with being prepared for anything by means of the correct wearable kit.20 What a Wizard carries is emergent from first principles— What do you use every day, multiple times a day? What are the tools you can’t do without?— and the container the kit is carried in is also emergent. It’s a question of ergonomics, of the body. The kit evolves and the kit’s kit evolves. Weight, durability, bulk. Ursula K. Le Guin, in her essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, conceives of a story as a bag: “A leaf a gourd a shell a net a bag a sling a sack a bottle a pot a box a container.”

She says that maybe thinking of the novel as a medicine bundle, as a great heavy sack of stuff including tiny grains of things smaller than a mustard seed, and intricately woven nets which when laboriously unknotted are seen to contain one blue pebble, an imperturbably functioning chronometer telling the time on another world, and a mouse's skull; full of beginnings without ends, of initiations, of losses, of transformations and translations, and far more tricks than conflicts, can function as an antidote to the tragic myth emergent from the linear, progressive, Time's-(killing)-arrow mode of the Techno-Heroic.

What does any of this have to do with stones? Well, there is that one blue pebble at the heart of the intricately woven net. I guess I think that the quality of carriability is Wizardly. I think that Wizarding is about what one carries— literally, in the sense of gear, but also in a more metaphorical sense: the human body as a container of knowledge. (In the case of folk-singers like me and Sammy, in one pocket of ourselves we carry songs. I think of the skin bag Aeolus gave Oddyseus, full of favourable winds.) It is non-utilitarian to pick up and carry a pretty stone, but we know for certain that our kind have been doing exactly that since the dawn of time.

As punctum, an object-lesson… Consider this Acheulean hand-axe, found in West Tofts, Norfolk, England.

The age of this artefact is debated. Some people say it is 300,000 years old, some say up to 500,000. In any case, it was made in the Palaeolithic, the Old Stone Age.21 This tool was not made by a human being— not Homo sapiens like us, but by an archaic hominin; or as one sculpture website names the maker, Artist Unknown. We know that 500,000 years ago hominins were living in what is now West Sussex, at Boxgrove. They were the robust Homo heidelbergensis.22 (Depending on dates, it is also possible this axe was knapped by a Homo neanderthalensis individual.)

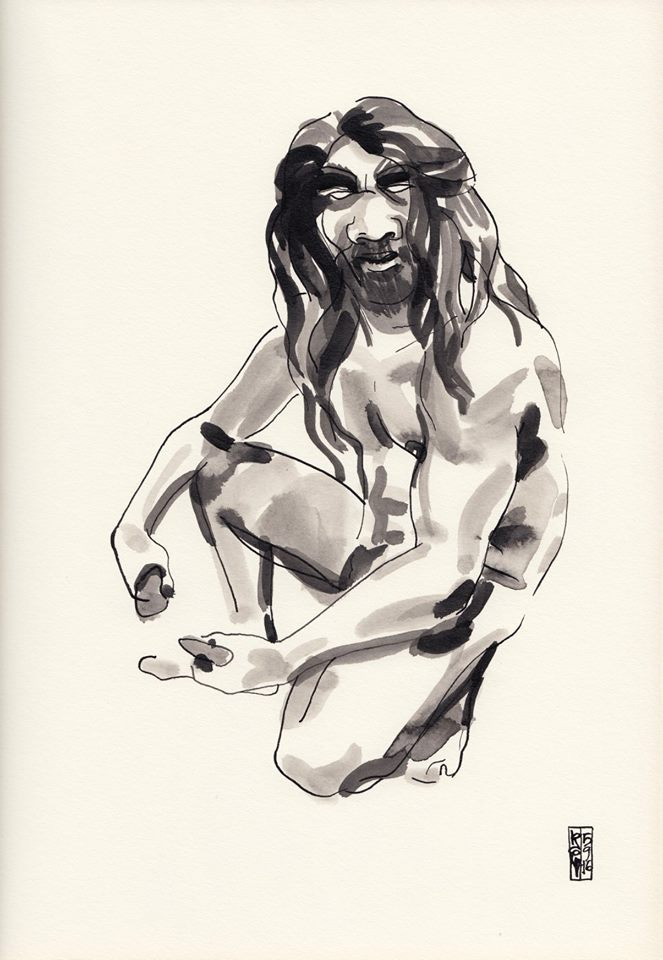

It is easy to imagine this piece in the hand, the maker turning and considering, the swift percussive taps. I went through a phase of making caveperson drawings, and I remember suddenly that I made one about flint-knapping:23

I captioned it a picture of your Great Great Grandad! Like most of this series, I made this drawing from a photo of a life-sized reconstruction that I stole off the Internet. I didn’t write down my source, but I have a hunch, and it doesn’t take me long to track it down— sure enough, it is Homo heidelbergensis. Something interesting happens when you take a static reconstruction and render it into another medium: somehow life comes in. It’s the same with taxidermied animals. The dead can be made to live again, limned in a living line.

Careful archaeologists spend a lot of ink trying to prove that the West Tofts handaxe could be unintentional rather than a piece of deliberate craft; we can’t prove that the shell wasn’t just a random impediment the maker paid no attention to.24 But… Look. Doesn’t it speak? This hand-axe is like an immortal seed. It’s not unbroken continuity that matters, but the enduring power of form. The detail I find most moving is the way that the face at the left comes right up to the edge of the fossil shell. They touch. To me that tells of beauty and craft— but even if intent can’t be proved, this piece of stone carries indubitable evidence of presence across half a million years: will and skill, cunning, the hand’s mark. I made this; I was here.

“The Master Hand looked at the jewel that glittered on Ged's palm, bright as the prize of a dragon's hoard. The old Master murmured one word, “Tolk,” and there lay the pebble, no jewel but a rough grey bit of rock. The Master took it and held it out on his own hand. “This is a rock; tolk in the True Speech,” he said, looking mildly up at Ged now. “A bit of the stone of which Roke Isle is made, a little bit of the dry land on which men live. It is itself. It is part of the world. By the Illusion-Change you can make it look like a diamond— or a flower or a fly or an eye or a flame—” The rock flickered from shape to shape as he named them, and returned to rock. “But that is mere seeming. llusion fools the beholder's senses; it makes him see and hear and feel that the thing is changed. But it does not change the thing...”

He looked down at the pebble again. "A rock is a good thing, too, you know," he said, speaking less gravely. "If the Isles of Earthsea were all made of diamond, we'd lead a hard life here. Enjoy illusions, lad, and let the rocks be rocks.”

(Ursula K. Le Guin, A Wizard of Earthsea)

“Nae king! Nae quin! Nae laird! Nae master! We willna' be fooled again!”

Like a child who babbles into a toy, emulating tones if not words

I’ve long thought that my ideal line of work would be just talking about my brilliant ideas. Seemed far-fetched, but… well… Here we all are.

I believe it is part of his series The Quick and the Dead, which I read as a riff on the formal similarities between the toki / adze form and that of handheld devices:

Short interview with Sheehan about this series here: Art Jewelry Forum - Joe Sheehan: The Quick and the Dead

As discussed in this essay on the principles of finding:

Under [My] Boot-Soles

Federico García Lorca: “We have said that the duende loves the edge, the wound, and draws close to places where forms fuse in a yearning beyond visible expression… But it’s impossible for it ever to repeat itself, and it’s important to underscore this. The duende never repeats itself, any more than the waves of the sea do in a storm…”

More Ötzi-reconstruction content on his channel: Ötzis Enkel. Ötzi lived in the Copper Age— a transition time between stone and metal. He had a copper axe with him. But he also had his stone dagger.

Up with this kind of thing! Oss Oss— WEE OSS!

The chalk is the remains of a prehistoric sea. Sometimes the flint forms fossils by filling a space that the body of a marine creature has left. Echinoid fossils were sometimes called fairy loaves or shepherds crowns. More on the super-old shit that has been found in the Thames here: Beach Combing - Mudlarking: Fantastic Beasts of the Thames

In this masterful lecture ‘Darwin’s bulldog’— naturalist Thomas Henry Huxley— proves evolution using the evidence of the chalk. On a Piece of Chalk - 1868

“Thus there is a writing upon the wall of cliffs at Cromer, and whoso runs may read it. It tells us, with an authority which cannot be impeached, that the ancient sea bed of the chalk sea was raised up, and remained dry land, until it was covered with forest, stocked with the great game the spoils of which have rejoiced your geologists. How long it remained in that condition cannot be said; but, ‘the whirligig of time brought its revenges’ in those days as in these. That dry land, with the bones and teeth of generations of long-lived elephants, hidden away among the gnarled roots and dry leaves of its ancient trees, sank gradually to the bottom of the icy sea, which covered it with huge masses of drift and boulder clay. Sea-beasts, such as the walrus now restricted to the extreme north, paddled about where birds had twittered among the topmost twigs of the fir-trees. How long this state of things endured we know not, but at length it came to an end. The upheaved glacial mud hardened into the soil of modern Norfolk. Forests grew once more, the wolf and the beaver replaced the reindeer and the elephant; and at length what we call the history of England dawned.”

Endure = to harden or tolerate, to bear hardness, to undergo or suffer, to be steadfast; linked with to dree one’s weird = to abide one’s fate or destiny.

In the modern age we use diamond tools, but they weren’t available back then, obvs

A treasured, precious thing. In this case I mean greenstone carvings worn as adornment

I found this great channel: Dry Stone TV. Better than watching the news…

Some flint wall images here: The Flintwall Co. - Flint wall types and flinting techniques

(It’s also worth looking at their ‘Work’ gallery for examples of beautiful contemporary flint-building.)

The Kipling Society says: “Daniel Hadas points out that the historical episodes in this poem are invoked in reverse chronological order, and all the specific allusions to places of origin are to places in or near Sussex. Also, the poem invokes the four storied attempts to conquer England: those of Caesar, the Vikings, William the Conqueror, and the Spanish Armada.”

A detailed breakdown of the references here: Puck's Song - Notes on the text

My satchel is more slimline, I guess because most of what I carry is flatter

Update: the sun was part of a drawing of Sam’s son with an entire cartload of potatoes, a vegetable he loves.

You can see some of Ötzi’s kit here: South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology - The Iceman's Equipment. Something to note is that in the old days there were masters of stone, as there are now— but also back then, everyone worked stone to some degree, as it was necessary for daily life.

Then— again, like Ötzi— there is what one wears in order to be prepared for any eventuality. A hat, for the sun. A coat, for warmth. Boots, for walking far. These two categories (carriable and wearable) overlap: form follows function in Wizardwear. I wrote about that here:

The Many-Pocketed Animal

Kenneth Grahame, Wind in the Willows: “He gave the name of the station that he knew to be nearest to the village of which Toad Hall was the principal feature, and mechanically put his fingers, in search of the necessary money, where his waistcoat pocket should have been. But here the cotton gown, which had nobly stood by him so far, and which he had bas…

The oldest evidence of hominins in Britain is the Happisburgh footprints, exposed briefly in 2013 on a Norfolk beach. Scientists used palynology (pollen grains) and analysis of fossils to determine that between 950,000 and 850,000 years ago, a small group of adults and children walked the mudflats of a river estuary. They are the oldest human footprints in the world, outside of Africa.

You can see a timeline of Britain’s prehistoric shapes here: Natural History Museum - The Making of an Island

It was postulated for some time that Homo heidelbergensis was the common ancestor of Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens— i.e. the Neanderthal cousins and us— but this is no longer widely accepted. The difficulty of determining who evolved into whom is known as ‘the muddle in the middle’ (i.e. the Middle Pleistocene).

To really blow your mind on amazing cavepeople paintings, I highly recommend the work of Finnish artist Tom Björklund. He does good dinosaurs too

![Under [My] Boot-Soles](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!9zGU!,w_1300,h_650,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F747e0a13-d880-401f-ad30-4e3e3c48c81e_956x956.jpeg)

I would love to travel my homeland with you one day. You seem so much more tuned into the finer details - the history and the natural world - than I ever was living there. Thanks for giving me a fresh perspective on the place.

Thank you for your wonderful wanderings and ponderings Rosie, such a rich weave.

The Acheulean strikes me as such a lively object, my hand gets this longing to hold it, to fit thumb on fossil shell. Not sure if that’s the scale, but that relation of hand and tool has some ancient magnatism.