Annie Dillard offers the following writing advice: “Write as if you were dying. At the same time, assume you write for an audience consisting solely of terminal patients. That is, after all, the case. What would you begin writing if you knew you would die soon? What could you say to a dying patient that would not enrage by its triviality?”

In trying to track down this half-remembered quote of Dillard’s— terminal patients, dying— I stumbled into a thicket of wrong search-results: things to say to a dying friend. You are so strong and brave; You’ve done so much to be proud of; Thank you for inspiring me with your strength. (Let me state for the record that if I were dying and people said such things to me, I’d be enraged.)

I got lost in a similar Internet forest last week, trying to find an essay I’d read online, in the before-time. I knew it was written by a woman, and I could see the illustration in my mind: fractured black trees on a green ground.1 The essay was about how it’s too late to reverse climate change, so we should treat the earth as a dying friend— that temporary, that precious. I couldn’t remember who’d sent it to me, or who I’d sent it to (my usual method for tracking shit down) because it was so long ago, in the early days of the Pandemic. I was searching things like apocalypse, end of world, woman, essay; getting back lists of the ten best essays ever written by women, and instructions on writing End of Days essays for Bible College.2

(Heather Christle ran into a similar search problem in the process of writing The Crying Book: “Look up ‘I’m not crying’ on Youtube and the first few hundred results display people— very often children at a school talent show— singing the comic song by Flight of the Conchords, in which they blame their tears on the rain. I am growing to hate this song. It is in the way of my finding evidence of people actually crying, actually denying it.”)

A few weeks back in Unity I was in a small cluster of, um, ‘creatives,’3 discussing The Times; Signs of, when suddenly Thomas (a clown) and I started finishing each other’s sentences. I’ve been more productive in the last few years … than ever before in my life. I don’t find it depressing, I find it … galvanising. (Funny peculiar. I joke sometimes that my natal Sun placement— stellium-set Leo Sun conjunct Jupiter in the Twelfth House4— hefts me to the destiny of a Wizard of the End Times. For all my pining for the irretrievable past, I think this is an amazing— if horrible— time to be alive. Things matter, here at the edge.)

A clown understands. Humour is one of those things that amateurs set aside in the face of death, but the sage dispenses like medicine.5 When people don’t know what to say to a dying person, part of that is the tendency to act all solemn and stiff, because, like, it’s serious. But, bro, take it from me— you are the one making it weird. Probably your dying friend just wants to hear the usual filthy jokes or gossip or whatever.

Dougald Hine published a piece last week that dances with the quote Even if I knew that tomorrow the world would go to pieces, I would still plant my apple tree. That made me think of Rebecca Solnit’s Orwell’s Roses, which I’ve written about before, here:

Vernalisation / Bread and Roses

Rebecca Solnit, Orwell’s Roses: “What is it that makes it possible to do the work that is of highest value to others and one’s central purpose in life? It may appear— to others, sometimes even to oneself— trivial, irrelevant, indulgent, pointless, distracted, or any of those other pejoratives with which the quantifiable beats down the unquantifiable.”

From Orwell’s essay Why I Write: “In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer… What I have most wanted to do throughout the past ten years is to make political writing into an art. My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice. When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, ‘I am going to produce a work of art’. I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing. But I could not do the work of writing a book, or even a long magazine article, if it were not also an aesthetic experience. Anyone who cares to examine my work will see that even when it is downright propaganda it contains much that a full-time politician would consider irrelevant. I am not able, and do not want, completely to abandon the world view that I acquired in childhood. So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the earth, and to take a pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information. It is no use trying to suppress that side of myself.”

Writing is a kind of speaking. Learning to write is learning to speak another language, with another tongue; finding a voice, they say, developing a voice. In life, it’s not always necessary to speak. Often it’s more appropriate or sensitive to shut up. But every craft has its rules, and the fundamental law of (non-fiction) writing is say what you mean. Learning to speak plainly is really unlearning: scraping back the layers of years of politeness / silencing— external, internal— to come to the naked self that speaks the plain truth.6

Driven by this new-fledged writer’s urge to say it plain, I find myself noticing the places guarded by silence-taboos.7 Even though every animal documentary comes freighted with obligatory climate change PSAs, even though every half-hour of news is a cluster of metastasising symptoms, it’s still semi-taboo to talk about it. (It = climate-change-induced societal breakdown = the end of the world as we know it.) It’s like humanity is collectively still stuck in denial, anger at best.8 Many people prefer to pretend things will be OK… somehow. I get it: it sucks. You feel bad. World-horrors we are helpless to remedy enter through the pupils and spread through the body, a drink of grief that strikes us dumb in our smallness and powerlessness. Day upon day, year upon year, events that would (in the more peaceful times of my childhood) have seemed shocking, shattering, come thick and fast, before there’s time to draw breath in between. The greatest unsayable is that this is life now: there’s no resting-place, and there’s no going back.

I was writing this piece, and it kept leading me down wrong-footed paths into swampy ideological ground. That’s not what I’m trying to say. I left the computer behind and went to Wellington Folk Festival. Between one thing and another, the last two Wellyfests haven’t happened,9 so it was my first proper one since 2020.10 The festival is where I recharge my Wizard-batteries by way of trees and birds and stream and moths, being loved and loving, and singing harmony for hours until everything in my body realigns itself, silver annealed in a flame. (I’d heard last year that a cellphone tower had been built nearby, and there was now coverage at the site, so I’d been worried that everyone would be on their phones and the magic would be ruined; but they weren’t, and it wasn’t.)

Wellyfest can’t easily be summarised. Too much goodness happens. It’s another kind of unsayable, the opposite kind: heart’s cup overflowing. Things that can’t be put into words— but it’s my job to try.

At the festival I ran into fellow Wizard Adam Mcgrath. For those of you who don’t know Adam, he’s a big beardy man covered with tattoos who dresses like a lumberjack, and every word that comes out of his mouth is driven by the passion that infuses his entire being. He wanted to tell me that even though we don’t know each other all that well, he loves my posts. I said thanks, man— and that I was planning to come to his workshop, ‘Service Through Spite’. No, don’t! he said.11

At the workshop— which was in the most beautiful, most chapel-esque room of the site, the Maire Lounge, a middle-sized wooden hall— Adam warned everyone that even though this thing was called a workshop in the programme, he was actually just going to talk about some stuff. He started out by telling about how after the Christchurch earthquake, in the face of the powerlessness he felt, he decided to play gigs for free for anyone who asked. He told about how he tried to find a generator to hire (there was no power, so generators were in short supply.) He found a man with one more generator left, who told Adam that you know, things being what they are, prices are different at the moment. Oh fuck, thought Adam, he’s going to gouge us, he wants a massive amount of money for the hire. “My price is…” said the generator man, “One Bruce Springsteen cover included in every gig you play.”

Adam then played the Springsteen song for us, and that’s when people started to cry.

As he continued his talk, the theme became clear; the title Service Through Spite started to make sense. He was talking about harnessing the power of anger at injustice, and using it as fuel for positive action. (As my ex used to say to his kid— Love and hate, two horns on the same goat.) Doing what you can: doing what’s right in front of you, and doing that again and again. As he spoke I thought about how it feels to write in what I think of as polemic mode. Writing from a place of anger is easy: it just comes out. It’s like vomiting— purging the poison. But with luck, what comes out of the process is less gross than a puddle of puke. (That’s the power of craft, folks!)

Afterwards, Adam and I walked and talked, on the green grass, under the apple trees just barely beginning to blossom, buds blushed pink. I told him about how just before I’d left for the Festival, I’d read this perfect essay by

(who was taught by Annie Dillard, who I quoted at the beginning of this piece)— On Becoming an American Writer.12 I tried to summarise for Adam what the essay had conveyed to me, and couldn’t. (This is the thing about the written word. The writer works their lump of ore, melting and hammering out what they have to say in the best way they can, then honing their edge, then more honing, then more, oiled blue Damascus. Whereas I, telling about it, scratch the outline of a knife in the dirt with a stick.) But this was the bit I was trying to quote:“What is the point [of writing]? I was asking myself that day… The point of it is in the possibility of being read by someone who could read it. Who could be changed, out past your imagination’s limits. Hannah Arendt has a definition of freedom as being the freedom to imagine that which you cannot yet imagine. The freedom to imagine that as yet unimaginable work in front of others, moving them to still more work you can’t imagine, that is the point of writing, to me. You may think it is humility to imagine your work doesn’t matter. It isn’t…

To write is to sell a ticket to escape, not from the truth, but into it. My job is to make something happen in a space barely larger than the span of your hand, behind your eyes, distilled out of all that I have carried, from friends, teachers, people met on planes, people I have only seen in my mind, all my mother and father ever did, every favorite book, until it meets and distils from you, the reader, something out of the everything it finds in you. All of this meets along the edge of a sentence like this one, as if the sentence is a fence, with you on one side and me on the other. When the writing works best, I feel like I could poke one of these words out of place and find the writer’s eye there, looking through to me…

All my life I’ve been told this isn’t important, that it doesn’t matter, that it could never matter. And yet I think it does. I think it is the real reason the people who would take everything from us say this. I think it’s the same reason that when fascists come to power, writers are among the first to go to jail. And that is the point of writing…

I wrote to [my students] that weekend and told them that art endures past governments, countries, and emperors, and their would-be replacements. That art— even, or perhaps especially, art that is dedicated somehow to tenderness, dedicated as a lover who would offer something to her beloved in the last nights they’ll share before she leaves this life forever— is not weak. It is strength.”13

Folk Fest is a longitudinal study in friendship. I see the same people once or twice a year, for a weekend. (It’s always a pleasure when friendships jump the fence into the real world— I’ve made some of my best friends at Folk Festivals— but I’m talking here about those I only see at Festivals.) A year is a span of time in which incremental changes always happen, and drastic changes also sometimes happen. The bigger gap this time meant bigger changes. Children had grown leggy, teenage. Many people were missing; new people had arrived. I spent minutes gazing into the universe inside the eyes of Pearl’s tiny baby, who is just learning to look back.

On Saturday night in the kitchen session, Tamara sang Home, Lads, Home.14 I said “Ah, you’ll make us weep,” (some songs reliably do that, like your heart’s a violin and the song’s a bow) and sure enough. The tears started, but once I started crying I couldn’t stop. I went outside into the night and leaned on the verandah rail. The air was as cold as water. I wasn’t sad, but some knot had been untied, and the tears fell down my face like a waterfall. It was something my body needed to do. When the weeping slowed, I went and washed my face, and stepped back into the session.

I can see commonality between the kind of writing I’m doing here— making liberal use of other people’s words— and singing folk songs. (That includes covers, like Adam’s Springsteen.) It’s a way of cross-pollinating my individual mind with the minds of not only the people I’m with in the flesh, but others I’ve never met, only heard or read; and with the legions of named and unnamed dead who went before, through whose breath the songs were shaped.15 The commons of folk music is so vast that a single person could never even hear all the songs and tunes of it, let alone learn them. Yet the people I was with over the weekend— my singing buddies— and I have an organic group-repertoire, songs that we know by heart, half-know, have heard before, always sing, or have learnt from each other. (This means that if a singer forgets a line or verse, someone else can usually remember it.)

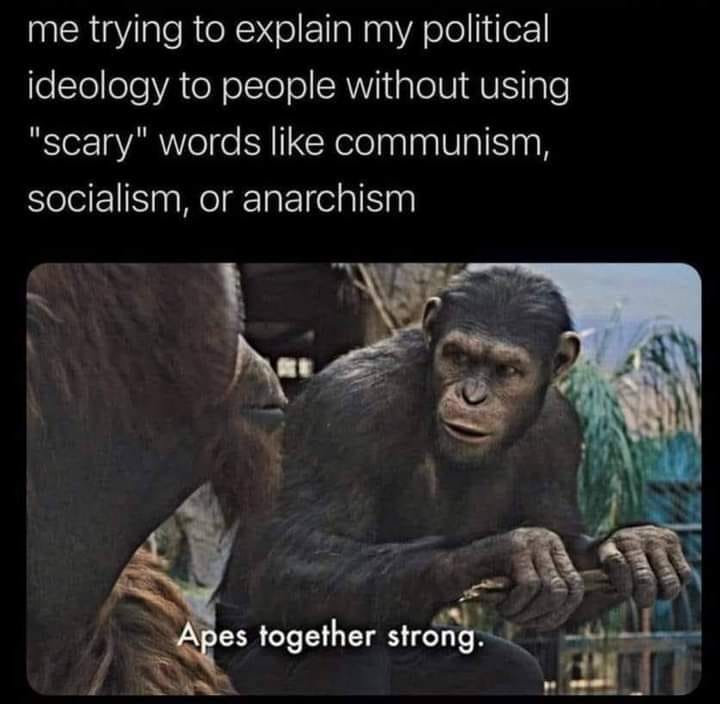

The kaupapa of the singing circle is interesting, in that nobody outright tells you the ways of it— you just absorb them over time.16 It’s inclusive: anyone can join or leave at any time (a typical age range: 18 - 85). It’s often loosely structured, in the form of taking turns around the circle (though a person doesn’t have to sing if they don’t want to— they can pass), but it’s anarchic17 in that nobody tells anybody what to sing or how to sing it, apart from maybe requesting a favourite song from a specific person. In joining in— adding your voice— the same anarchy applies. It’s not like a choir, where certain people sing certain parts with precision: anyone can put their voice wherever they like, and the sound that emerges from ten or twenty mouths is like a great living animal, or like a church ringing all its bells at once.

It’s not the sound alone, though, that makes the feeling: it’s the words— words that are a distillation of hundreds of years of being sung like this, songs polished by hundreds, thousands of minds and mouths, songs that are about things that people thought important enough to learn and sing about for all that time. If that’s not magic, I don’t know what is.

Solnit on Orwell again: “…this beauty in which ethics and aesthetics are inseparable, this linguistic beauty of truth and of integrity as a kind of wholeness and connectedness, between language and what it describes, between one person and another, or between members of a community or society.”

Let’s assume for a moment that the blackest assessment is correct, and the world really is a terminally ill loved one. How much time do we have to get real with the dying process? I’m frustrated and bored with the mass cognitive dissonance. Fantasism is not going to work, hedonism is not going to work: creativity and magic are the medicine, and those only work if you are willing to labour in service of truth and beauty. Time moves only forward, never backwards! This is the only life we have— these are our times! What if the imminent end of the world means that whatever’s yours to do or say, you should do or say it right now? Can we all please get through the denial-phase, and into reality, and start to live here and now?

I often think of these lines from the climactic song of Inside, the lockdown project of the black-comedy raw genius Bo Burnham, whose work is all about looking into the abyss: You say the ocean’s rising, like I give a shit. You say the whole world’s ending, honey it already did.

On the last night of the Festival, I left the singing around 3 a.m. and stood indecisive on the grass, not quite ready to end things by going to bed. I could feel the famous cold nipping at my ankles. Suddenly I remembered the fire. Fire. Warm. Yes. Orange. Yes. I could see and feel it in my mind.

(I’d been at the fire earlier on in the weekend, when I’d lost my shit at some innocent tweens for taking photos of their toasting marshmallows on their phones. The living night forest all around, the huge old-man pine overhead holding the half-moon in its black branches, fire-glow-lit human faces. They were sitting cross-legged in a row at the edge of the flames, and two of the five of them had smartphones in their hands— the phoneless kids leaning in18— enraptured by the cold white screens. Kids on phones always break my heart, though I generally keep my mouth shut about it; but this was the last straw, phones at the festival. I opened my mouth and it fell out. “THAT’S not the real world.” I said. “THIS is the real world.”)

I walked over to the fire, where three young people with a guitar were singing Mountain Goats and other bands I didn’t know. Then Tom sang a song that I knew had to be Bo Burnham, and we had a yarn about the genius of Bo. I mentioned That Funny Feeling, which Bo plays on an acoustic guitar, with a fake campfire and tree-silhouettes projected onto the walls of his lockdown room, but they said they’d already played it before I arrived, and couldn’t bear to sing it again: it’s about the end of the world.

Then a man with a mandolin stepped into the firelight. A few songs later he told us how he’d learned songs at Quaker Youth Camp, and I said I knew a Quaker song: John Ball.19 We sang that together— I sang and they joined (Who’ll be the Lady, who will be the Lord, when we are ruled by the love of one another? Who’ll be the Lady, who will be the Lord, in the light that is coming in the morning?) and then we sang a Quaker round, voices interweaving (Dear friends, dear friends, Let me tell you how I feel, You have given me such treasures, I love you so). Then mandolin man asked me, do you know the Diggers Song? Yes. We sang The World Turned Upside Down (You poor take courage, you rich take care. The earth was made a common treasury for everyone to share. All things in common, all people one.) Then we sang The Magnetic Fields and Tom Waits. Do you know this? Do you know that? the man with the mandolin— Hugh— kept asking me, and I said yes, yes, yes; it was uncanny— we were like new-met music-twins. Tom and friends sang wonderful intertwined songs from Hamilton: the Musical, standing in the firelight.

(Written out like this on the page,20 these lyrics seem unbearably simple-minded. Sung, they moved me, all the more for being sung with people I’d only just met, by a fire, at 3.30 a.m. on Labour Day morning.)

At some point over the weekend, I said to Kev, “I wish we could just live like this all the time.”

Kev: “You say that every single year.”

Me: “Because it’s true!”

Kev: “I mean, this is basically Socialist Utopia.”

Me: “Well, we don’t work here. But it would be just as good if we did.”

I want life to be like THIS, not like THAT. Why can’t it? Serious question: why can’t we live in Socialist Utopia21 all the time?

I came home and dreamed about two falcons courting, riding the air so close together that they overlapped, seeming one single bird.

Rebecca Solnit says in Hope in the Dark: “Joy doesn't betray but sustains activism. And when you face a politics that aspires to make you fearful, alienated and isolated, joy is a fine act of insurrection.”

Adam— who transformed himself from a “little scumbag” into a Big Heart-Wizard through the power of politically-driven art— said, in his Service Through Spite talk: “I’m a folksinger. That’s what I call myself. What’s the difference between pop music and folk music? Pop music is about love, love, love. [Romantic love, he meant.] And folk music is about everything else.”

Further advice from Annie Dillard: “Spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time. Do not hoard what seems good for a later place in the book, or for another book; give it, give it all, give it now. The impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. These things fill from behind, from beneath, like well water. Similarly, the impulse to keep to yourself what you have learned is not only shameful, it is destructive. Anything you do not give freely and abundantly becomes lost to you. You open your safe and find ashes.”

What would you begin writing if you knew you would die soon? (Spoiler: you will die, maybe sooner, maybe later. Sing while there’s breath in you to sing with.) Speaking from the heart is deeply embarrassing, and terrifying, and important, and necessary. It’s a leap of faith. It’s the gift that makes your work alive. It’s taken me years— decades— of unlearning to even begin to try and do it. But if you fake it, what you make is half-dead. Art-law: there’s no choice but to be real. That means dropping the veneer of cool, looking like a naïve idiot, risking fucking up, and knowing you might regret it later. What bow plays your heart’s violin strings? What are the medicines— for you personally— that are antidotes to the poison of world-news-induced despair and grief? Feel the fuck out of those feelings; then take the medicine, and get back to work.

Like when you go into the bookshop and say “I’m looking for a book. The cover was red, with a bird on it.”

I found the essay in the end, by eventually remembering who’d shared it— but it’s been taken down. https://www.catherineingram.com/facingextinction/

A poet, who I quoted in my last piece; a general mover-and-shaker who is hard to sum up in one word; and a clown.

Like a big old solitaire diamond. H8rs gonna h8

I remember the sterile anteroom of a hospital late at night, me and my Mum and my sister hysterical with laughter.

Scratch a cynic, find a wounded romantic.

The feeling of biting one’s tongue = the emotional hallmark of the zeitgeist.

On a global-politics level, this denial-anger cocktail spawns strongman ego-fantasies of returning to a glorious past.

I kept saying it was three, because it felt like three, but it wasn’t. It was two, which makes a three-year gap. One was cancelled: we had a tiny one instead, with less than 100 people and no invited guests. Last year, the first proper one, I missed because I’d been exposed to Covid a few days earlier. (I couldn't even go and do anything else to distract myself: I had to sit at home alone for the whole weekend.)

I remember the feeling of the 2020 Festival well. It was during ‘Fortress NZ’, when the rest of the world had Covid but we didn’t. I remember standing at the back of the big marquee during the final concert; a Serbian singer, her gold-stitched garment glinting under the stagelights; people dancing on the grass; knowing it for the end of something sweet that would never return— thinking, remember this.

Self-effacingly

I’d love to copy out the whole thing for you, because I can’t find it online. Please find and read the whole thing if you can: I found it in Chee’s book of essays that I bought the other week, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel.

My emphases

Here it is sung by the wonderful Paul Sartin (of blessed memory) who I first heard this song from, at Auckland Folk Fest 2020: Home, Lads, Home

Through whose hands the books were made.

Teaching is mostly by way of modelling, rather than telling. When I see the young people in the circle, learning their own voices, I remind myself of how little I knew when I first started, and am so happy to have them there.

I mean anarchic here in the literal sense that nobody is the boss of it.

Though the one at the end of the row, possibly a Steiner kid or homeschooled, just looked generally bored and miserable.

Written by a Quaker— Sydney Carter.

The screen

Thank you for saying what you mean! May a cascade of saying-what-we-mean end this age of deadening denial. Capital has already foreclosed so much, we may as well do and say what’s real, in/to spite

I was outside, enjoying myself by a creek with my cat and a friend when I read this. Would you have yelled at me?