Mary Ruefle, Glory:1 “I am a glorifier, not very high up

on the vocational chart, and I glorify everything I see,

everything I can think of. I want ordinary men and women,

brushing their teeth, to feel the ocean in their mouth.

I am going to glorify the sink with toothpaste spat in it.

I am going to say it’s a stretch of beach where the foam

rolls back and leaves little shells…

I met a psychic who told me my position in the universe

but could not find the candy she hid from her grandkids.

The ordinary fear of losing one’s mind. You rinse the sink,

walk out into the October sunshine, and look for it

by beginning to think. That’s when I saw the autumn aster,

the sedum blooming in a purple field. The psychic said

I must see the world glory emblazoned on my chest. Secretly

I was hoping for a better word. I would have chosen for myself

an ordinary one like orchid or paw.”

I found the first orchid in a skip, back in July. It still had yellow gift paper tied around its pot with a ribbon, and a few wilted flowers clinging to its spike. Come with me, little friend! I had been coveting Phalaenopsis / moth orchids for a long time, but paying $50 or $60 for any plant— well, I won’t. At the peak of the houseplant-craze of the last few years (was it prompted by lockdown, maybe?) certain plants acquired an almost mystical cachet, like tulip bulbs in the 1630s. People were selling tiny cuttings of the anointed kinds for hundreds of dollars. But, much like my Thoth deck, which I found in a bus stop, I wished hard enough for long enough that the orchid eventually came to me for free.

I boned up on repotting techniques and ordered a special clear pot online. When I went to Bunnings for orchid potting mix, I saw another bedraggled orchid-child knocked down to $9, so I bought that one too. It still had buds on its flower-spike: I left the spike uncut.

When I was a wedding photographer’s assistant in the early 2000s, white moth orchids were the fashion.2 Orchid bouquets, orchids in the hair. It’s logical, because orchids are a curious mix of delicate and tough: ephemeral in appearance, yet long-lasting. Their petals are almost like human skin, or like slivers of flesh; opaque sashimi.

When I repotted the rescue orchids, I discovered that each had a tight corset wrapped around the middle of its roots. Rubbery and brown, it was the remnant of the substrate the plants had been germinated in. I broke it apart and picked it off the roots. Phalaenopsis are sold in supermarkets, hardware shops, florists, in the flush of their first flowering. A living bouquet, an expensive hospital offering, a sophisticated birthday present. But once the flowers finish, people don’t know what to do with the plant. It begins to suffer, and people throw it in the skip. This stranglehold, hidden in the bark, made me understand why. How can a being continue to thrive, throttled like that?

I wanted to know how they are cultivated. I found this video of a massive Phalaenopsis factory in the Netherlands (watch it on mute because the soundtrack is just bad music the whole way through):

In the video, the orchid plants are ready for sale at 70 weeks— five and a bit seasons. That’s why they cost so much: growing time. Kev says he thinks they are grown by tissue culture in a laboratory (as seen in the video at 0.45). This would produce sterile clones of the parent plant, circumventing biosecurity regulations. The New Zealand grower would receive the tiny plants in plugs— the aforementioned rubber corset— and plant the plug directly into the bark substrate to grow them on. (If this theory is correct, the orchids we buy here can be sold as ‘grown in New Zealand’— but they originate elsewhere.)

Researching further into the plug— what exactly is it made of? Ground up car tyres, says Kev, joking. I think it is probably something like this: Proptec (TM) Xcellent Plug (R).3 I discover that on r/orchids it is known as the death plug or the plug of death. Kev thinks that potting on the baby orchids still in their plug is a matter of pure expediency, but a cynic might call it built-in obsolescence.

Six months on, the dumpstered orchid had grown a new leaf, and a new root.

Taking this as proof of my orchid rehab-abilities, I acquired two more at knockdown prices.4

Then, back at Bunnings one more time for moss (to mount my staghorn fern on driftwood)5 I saw another $10 orchid, brutalised: I think it had been stood on, as well as starved of water. I cut the flower spikes back, soaked it in rainwater, and repotted it, and a few days later its loppy leaves were shiny racing-car green, its roots verdant.

Orchids seem sentient, like hoyas; there is something animalish about them. Maybe it’s because both Phalaenopsis and Hoya are jungle epiphytes, creatures of water and air rather than earth. To the human eye, their beauty is their use. They are plucked from their own places and turned into a product, like a factory-farmed chicken. Considering that a wild orchid might take 8 or 10 years to flower, 70 weeks is nothing. Force-fed to the favoured state: the fat pullet, the orchid in virgin bloom. Maybe it is better not to be so beautiful or tasty. Maybe it is better to be below human notice, to be ugly or bitter or small. Or old.

Walking on the beach in the less fierce heat of the evening, I found this plughole. (All that talk of plugs.) Then I found someone’s tiny gallery: calligraphed stones laid out on a driftwood tree-root. I chose one, carefully.

The six spokes— and the numbers 1 to 6 on the scarf I hung over my orchid hospital— make me think there is one more orchid still to come. Sources and sinks: seeing beyond the cellophane wrapper to the living being, snatching it from the jaws of the dump. (I wrote about scavenging here:)

Free Shit: A Rubbish Manifesto

Rubbish is free: it costs nothing. Its assigned monetary value ranges from almost nothing (Dump Shop); to nothing (things scavenged from bins or gutters, reclaimed recycling such as glass or cardboard); to less than nothing / negative value (i.e. being paid to tear down a shed and take away its constituent parts, or clear garden waste).

Kev reminded me about his friend Sean, who decided to turn his lawn into a wildflower meadow. Sean lives in Sussex, at the foot of the South Downs. He stopped mowing in Summer and wild orchids flowered in his meadow. Were they there all along, cryptic among the mowed grass? Kev says: “Early purples and common spotted only grow on chalk / limestone as far as I know. I've seen bee orchids on clay as well, and twayblades like woodland leafmould. Lack of soil disturbance and low soil fertility are important.”

It took me a while to search out these photos (I eventually found them in the comments section of my Autumnal Equinox post— a photo of a huge Amanita muscaria and my boot-toe plastered with wet graveyard leaves).6 That night I dreamed a woman gave me a large silver brooch: a repoussé moth, with wire legs and antennae.

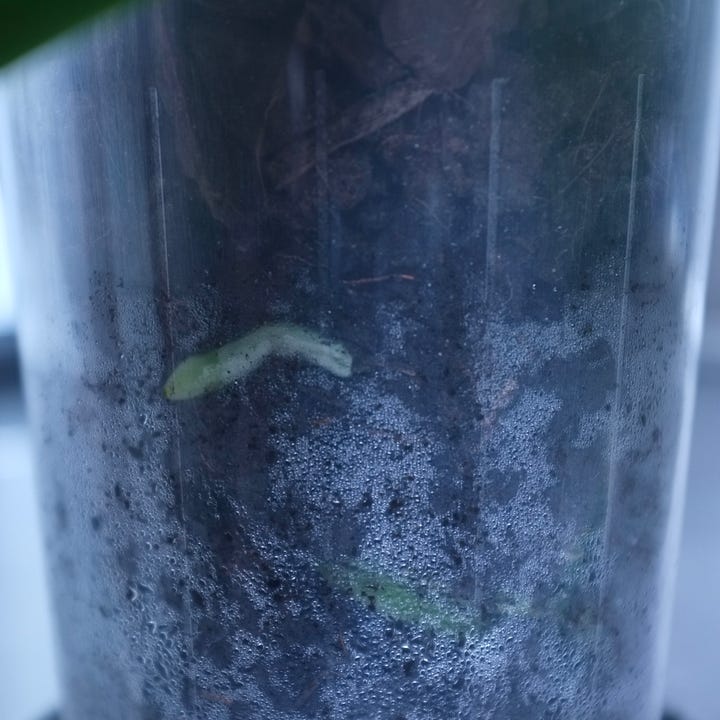

My interior rewilding efforts brought the following new species into my house. Tempting as it was to let it take up residence, I relocated it back into the more stickish outside world.

We have our own Aotearovian orchids too, of course. They are bush-dwellers, small and subtly coloured, and I’ve only ever seen one once in my life. I remember the memory of its scent.

Meanwhile, the other humans have been behaving strangely again. In clock-time world the ‘New Year’ is the season to publicly proclaim all the things you did last year and all the things you resolve to do in the year to come. In ‘the Summer holiday’ it is the time to lie around doing nothing, and to eat a lot of food— so much food that you have to pause and wait for the sausage factory of your gut to make a bit of space before you can stuff more in.7 Humans do this because the way they usually work is unpleasant. It’s like in Katherine Mansfield’s At the Bay:8

“And so you go back to the office on Monday, do you, Jonathan?" asked Linda.

"On Monday the cage door opens and clangs to upon the victim for another eleven months and a week," answered Jonathan.

Linda swung a little. "It must be awful," she said slowly.

"Would ye have me laugh, my fair sister? Would ye have me weep?”

I kept thinking: For them it’s a holiday, but for me it’s a holiday from my holiday. Not like how people get home from some complicated overseas trip and say “I need a holiday from my holiday,” but more like— I don’t enjoy doing nothing at all for very long. In my way of life, stopping entirely is an upheaval, just as big of an upheaval as it would be if I went back to the old nine to five.9 No, the kind of spaciousness I like is the never-working / always-working juggling act of Wizarding. If I drop the balls, there’s a break in my rhythm and I have to begin again. I prefer my work to be a river.

When I worked in offices, which I did for a decade on and off, I would often find myself behaving strangely outside of work time. I remember vividly the ecstatic endorphin rush that would hit me when the minute hand finally hit the 12 and I stepped out into the street after work. Usually this was Lambton Quay, and I would gaze blissfully at the opalescent clouds, and the birds flitting from tree to tree in the concrete canyon, and the lordly gulls high above, crossing to the inner harbour for the evening. And the bureaucrats, how I loved them in that moment of freedom! I would play my game of trying to catch the eye of a live one.

Then I’d want sugar, or mind-alteration, or to buy something, to spend some of the money I’d traded my time for. I’d want to stay up late and do some of my own work to make it feel like my life still had self-made meaning.10 Around midnight I’d tear myself away to shower and bed, then wake to the alarm ten minutes before the morning bus and stagger into my clothes half-asleep, only waking up with the first office coffee. Caffeine and alcohol: the twin horses of capitalism. One to shock you awake, one to bludgeon you into a kind of dumb joviality. Start now! OK, stop now! Don’t worry, these aren’t even drugs— they are food!

Holiday means holy day. I know my life is not like other people’s; for a Wizard, unceasing 無為11 is the only way. Humour me for a minute. In my Utopia, everyone would be free to follow their vocation. Dougald Hine says that embeddedness in a living culture is a human birthright. I believe that intrinsic, meaningful work is also a human birthright, but it’s one we’ve all been kept from for so long that even the memory of that way of life has been severed from our consciousness: an ideological colonisation process. Humans were never paid to work before there was money— yet they worked: to survive, to live, to express their energy, to experiment, to play. They play-worked, as Ursula Le Guin calls it in her self-portrait-as-Oppenheimer, The Dispossessed.12

When 2023 began I thought of Eris and her golden apple. (Long story short: the Discordians— chaos magicians— worship Eris, the Greek Goddess of chaos. Also, Discordians have a thing about the number 23, popularised by the novelist Robert Anton Wilson,13 back when conspiracism was still fun.) But 2023 turned out to be the year I got re-radicalised.14 I managed to break the constricting rubber out of my own substructure. I moved house, and I replanted my efforts here, in the soil of Substack, pressed up against the transparent edge of the screen. I reached out my roots and touched mycelium. For the first time in my life I am experiencing the full free-flow of the correct state,15 and the joy of it makes me angry. Why shouldn’t people have what they need?

(I wrote previously about housing and houseplants here:)

Of Hopeful Green Stuff Woven

Heather Christle, The Crying Book: “Writing a poem is not so very different from digging a hole. It is work. You try to learn what you can from other holes and the people who dug before you. The difficulty comes from people who do not dig or spend time in holes thinking that the holes ought not to be so wet, or dark, or full of worms. ‘

In the days of film, when photos were artefacts, I often found them. Now, almost never. Walking down Leeds Street towards Goldings and the Hanging Ditch, past the bar punters chattering in the afternoon sun like a tree full of sparrows, I saw a photo lying face-down in the gutter.

The more I look at this, the more I see. Baby’s orchid-face, her outspread toes, her amber teething beads. The tender pose of the man, who (according to the ballpoint inscription on the back) is not her Father but her Uncle. The radiant light through the curtain. This image is a window into somewhere else, a plucked piece of waterfall.

Tip of the Wizard hat to Emily Berry who brought this poem to my attention by way of the London Review of Books.

Here you can hear Ruefle reading the poem: she says “piss or paw” rather than “orchid or paw.” Mary Ruefle - Glory

Other poems here: Voetica: Mary Ruefle

Are they Phalaenopsis amabilis, the ones called called anggrek bulan— moon orchid— in Indonesia? Or are they Phalaenopsis aphrodite? Friendliness or love?

This is an Australian company: do our orchids come from Australia, then? It seems likely— Phalaenopsis are native there, as well as in India, Taiwan, China, Southeast Asia, and New Guinea.

I recently read Tracy Sorensen’s amazing book about her cancer, The Vitals, which made me think about guts in a different way. Her internal organs are the characters. The cancer is named Baby. The Uterus is named Ute, and the ovaries are a pair of kelpies (Sorensen is Australian). It was very educational and funny, and I highly recommend it.

The whole story is here: At the Bay. The Bay in the story, fictionalised as Crescent Bay, is Wellington’s Eastbourne.

Eight to six

In ADHD-world this is known as revenge bedtime procrastination. 2023 was the first year of my life that I got enough good quality sleep. I discovered I am a morning person. Who knew!

Wu wei: roughly, effortless action

Oppenheimer was a friend of Le Guin’s parents, and she has said he was her model for the character Shevek; but on another level The Dispossessed is a portrait of the artist at work— my read is that physics is a proxy for writing. Searching the 404 instances of the word work in the text, I found this: “Most Defense work was so boring that it was not called work in Pravic, which used the same word for work and play, but kleggich, drudgery.”

(See also: David Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs— this is the initial essay, later expanded into a book: David Graeber - Bullshit Jobs.

Also see also: Peter Kropotkin, in his 1892 book The Conquest of Bread, which I got in the Dump Shop last week for $2: “Somebody has said that dust is matter in the wrong place. The same definition applies to nine-tenths of those called lazy. They are people gone astray in a direction that does not answer to their temperament nor to their capacities… Very often the idler is but a man to whom it is repugnant to spend all his life making the eighteenth part of a pin, or the hundredth part of a watch, while he feels he has exuberant energy he would like to spend elsewhere. Often, too, he is a rebel who cannot submit to being fixed all his life to a work-bench in order to procure a thousand pleasures for his employer, while knowing himself to be far the less stupid of the two, and knowing his only fault to be that of having been born in a hovel instead of coming into the world in a castle.”)

Then I found this: “When Shevek was nine his afternoon schoolwork for several months had been caring for the ornamental plants in Wide Plains community— delicate exotics, that had to be fed and sunned like babies. He had assisted an old man in the peaceful and exacting task, had liked him and liked the plants, and the dirt, and the work. When he saw the color of the Plain of Abbenay he remembered the old man, and the smell of fish-oil manure, and the color of the first leafbuds on small bare branches, that clear vigorous green.”

(In the context of barren Anarres, ‘delicate exotics’ means ‘plants with leaves’— maybe fruit trees, or something like that— rather than ‘ornamental orchids’.)

And finally I found the passage I was looking for: “He worked better in the private room. The job was worth doing and he was doing it well. It was centrally functional to his society. The responsibility justified the privilege.

So he worked.

He lost weight; he walked light on the earth. Lack of physical labor, lack of variety of occupation, lack of social and sexual intercourse, none of these appeared to him as lacks, but as freedom. He was the free man: he could do what he wanted to do when he wanted to do it for as long as he wanted to do it. And he did. He worked. He work/played.”

(Though Wilson attributes the concept to William Burroughs.) The apophenia is the point— a feature, not a bug.

I like the Discordians because they have a sense of humour. Alan Moore, comic book writer and magician, worships the obscure Roman snake god Glycon, who is thought to have been a hand puppet. Although Moore calls himself a Hermetic rather than a Chaos magician, I feel his choice of personal deity is a chaos-flavoured one.

Latin radix = root. A meta-root word

As expressed in Virginia Woolf’s famous phrase that— if female— “it is necessary to have five hundred a year and a room with a lock on the door if you are to write.” (She says fiction or poetry, but the principle holds.)

Meadow update from Sean in Sussex:

"Year has now turned and we are now looking towards the lengthening days. We're in a cool snap this week but the ground is very wet from the months of precipitation. The 'meadow' is in a confused state - the primroses are well on their way but the grass needs to be cut short to encourage the orchids. Last year we sadly had no bee orchids due, we think, to me not keeping the grass short over the fallow season. We have learnt. To add to our list of indicator species I found adders tongue fern in one section this year. I'm sure it's been here doing it's thing year after year without us even being aware and giving it a severe haircut everytime the grass was cut.

I managed to get myself organised enough to cut the grass with the scythe I bought after doing a course the year before. All a bit flailing and a lot of hacking due to the rough grasses and Rag wort.

The area has now been truely trashed by foxes and badgers digging for the wildlife that has obviously enjoyed the new found 'wilding' 😄.

Subzero temperature here at the moment so anything that has made growing moves over the last few months is bound to be a bit chillsome for a few weeks!"

I cannot for the life of me pinpoint why I like these rambles so much which is clearly why I do. Let us all wizard our way through these days...