This piece contains a lot of images: it will get cropped, so click through from email and read it on Substack.

Terry Pratchett, Guards! Guards!: “There are many horrible sights in the multiverse. Somehow, though, to a soul attuned to the subtle rhythms of a library, there are few worse sights than a hole where a book ought to be.”

William Shakespeare, The Tempest:

“…so, of his gentleness,

Knowing I lov'd my books, he furnish'd me

From mine own library with volumes that

I prize above my dukedom.”

Moving house is a disruption in rhythm. Time changes from cyclical to pointed, everything counted backwards from the end. This by then. That to occur at such and such a date, then that, then that. I don’t like thinking that way, not at all. While I’ve lived here I’ve written a lot about time— slow time, felt time, nature time; and how older ways of being (in) time tug against modern time, clock time, the unpresent.1

Among the disrupted rhythms is the rhythm of my Substack posting, which had been weeklyish: not planned that way, just emergent. I was worried that I wouldn’t be able to write at all during the disassemblage, but instead I’ve been writing shorter, more frequent, less worked updates. Each of these diaristic posts feels like an acorn stashed away against the Winter of true upheaval that’s coming in a few weeks time.2 Gather ye rosebuds while ye may!3

In reality, in nature-time, it’s full Spring. Some of you will remember the story of how a few months after I moved into the cottage I rescued a thrown-out Phalaenopsis orchid from a skip in Island Bay, with the yellow wrapping paper still tied around its pot and a few dried purplish flowers clinging to the stem.4

Once I had successfully repotted the dumpstered orchid— once it grew a new root and a new leaf— I became drunk with the possibility of orchid-keeping, and rescued four more reject Phalaenopses from Bunnings.5

Orchid Hospital

Mary Ruefle, Glory: “I am a glorifier, not very high up

on the vocational chart, and I glorify everything I see,

everything I can think of...

In my first year of orchiding I was happy with new leaves and roots as signs of rehabilitation. I knew that it was a difficult thing to get an orchid to rebloom, and my orchids in particular were rescue orchids, i.e. not the most robust specimens to start with, and I live in Wellington, a notoriously weatherish city, so I wasn’t confident of ever coaxing new flowers out of them.6 Maybe they would just be little green friends for a few years, or maybe forever. That was cool by me. Then in June— that is, Aotearovian Winter— I dreamed that my orchid was flowering. I went to check, and found that the dream was true: the skip orchid was making a flower shoot.7

I knew that you’re meant to switch fertilisers when flower spikes appear, so I ordered this one off the Internet. (I later discovered that my favourite plant shop in Wellington, Turtle Therapy, also stocks this range. Turtle Therapy is a truly Wizardly place, a temporary autonomous zone8 of green magic, and you should definitely go there if you can: it’s down the Left Bank.) Anyway, when I started spraying this fertiliser onto my orchids, even the ones that weren’t flowering started growing fat roots.9

As I watched the flower spike grow…

And grow…

And grow…

…I thought a lot about how this orchid in particular was metaphorical, symbolic of my habitation in the house; rescued, resettled, happy in its work— living proof of my ideas about correct conditions leading to creative flowering. I was curious, too, what colour the flowers would be. I hadn’t seen them first time round, only those dried purple scraps of petal-paper.

Then I was given notice on the house.10 Of all the wrongnesses, somehow the prospect of the orchid’s flowering being interrupted by a change of environment annoyed me the most. It was doing such a big flowering! Four stem’s worth! I felt like I had implicitly promised the plant stability, and now I was having to go back on my word.

Very reluctantly, I started the dismantling. The orchid wasn’t bothered. By last week, I could see the first bud was almost ready to open.

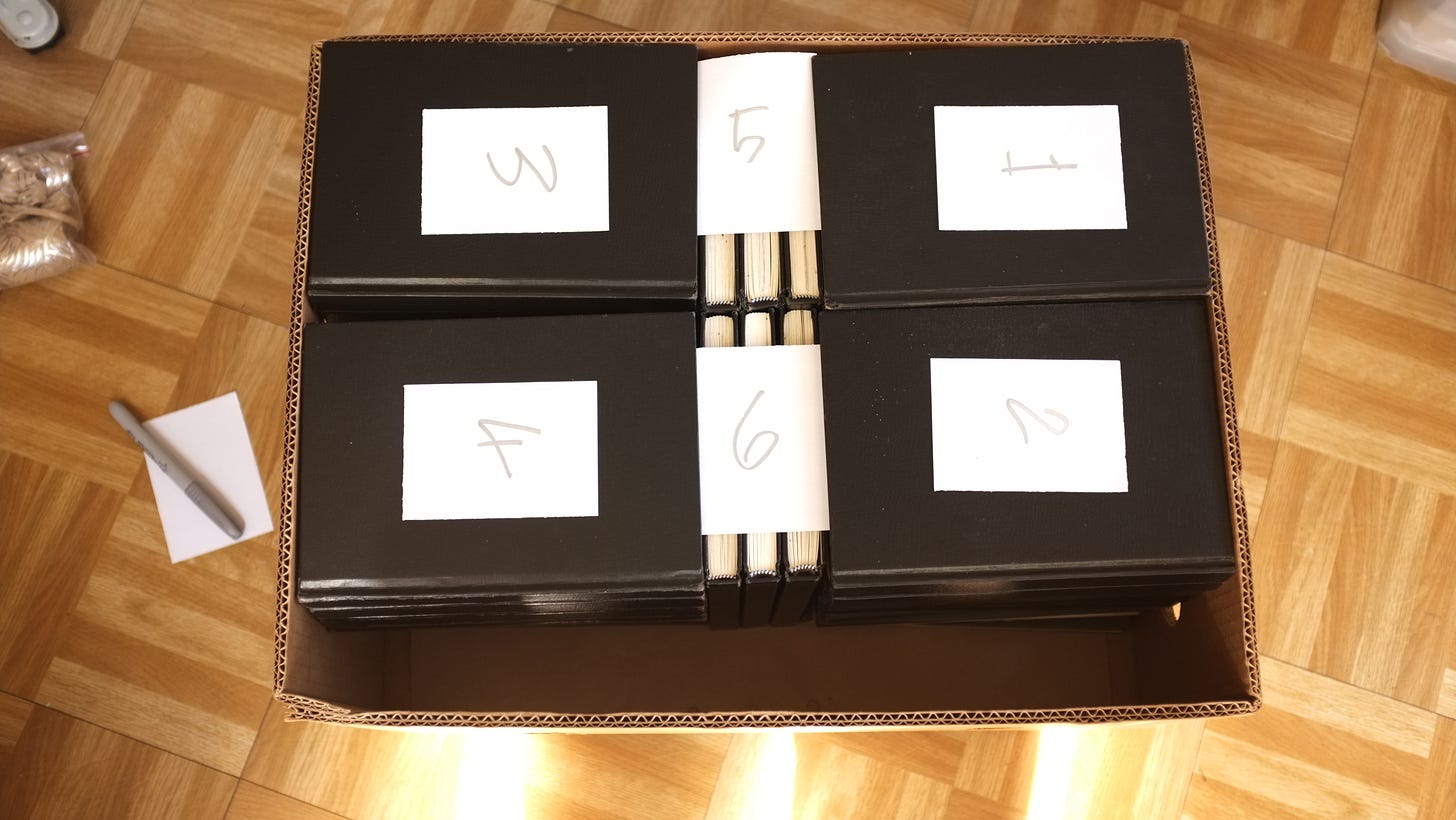

I packed all my journals and drawing books into boxes. The drawing books had to be packed out of order, which hurt me in my archivist’s soul— but it’s more important that they be securely packed than that they be chronological; I had to let order go.

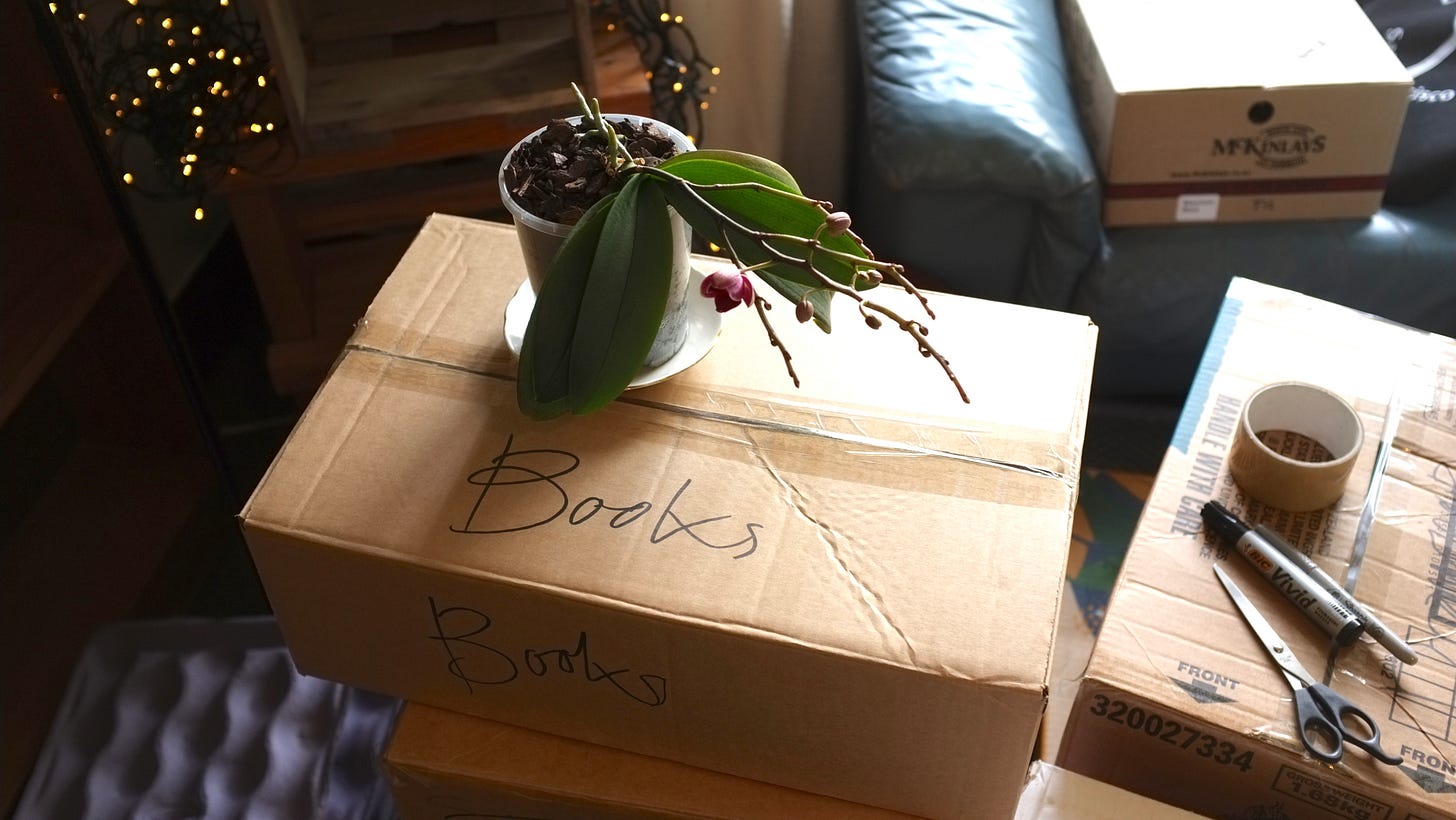

Then, yesterday, I packed all of my books into boxes. (Books by other people, I mean now— essays, memoirs, novels, poetry, reference, art books, etc. etc.) In New York,

has just undergone the same process.11 She wrote: “This was supposed to be an essay about the good part of giving away your books. The keep-the-books Defense says, ‘It is a sad and failing scholar who has to see her books go before that sadder day when her books have to see her go.’ In a smaller world. In a bigger house. Life would have been easier on us.”I decided not to throw any of my books away. The prospect of the decision-making process was too heavy, and it was scaring me into inaction. It would be easier, I decided, to just pack and store them all. Better a few more trips up and down the stairs than a pressurised splitting of my book collection, the external mind of my writing-selfhood. So yesterday I packed all my books into boxes, breaking down my library, which was ordered by subject, antiquity, size, colour— in short, it was a personal system; but in packing, the books became objects, puzzle pieces to be fitted together in such a way as to keep them all foursquare, tensioned against each other.

There was a gap in the last box big enough for three more books. That bugged me, so I left the box open overnight. This morning I remembered a three-paperback pile stashed elsewhere in the house, fetched it, plugged the gap, and taped the last book-box closed. Then I looked over at the orchid: the first flower was parting its petals in the morning light, revealing its interior theatre of colour.

Closer.

Closer.

The speckled tongue to entice a bee, the grooves of the lip a dancing floor, the bird’s beak of the pollinia; and the colour (magenta) that a stranger chose for another stranger— who threw the plant away once the flowers were done.

A plant’s time is like that of a baby being born, or like death: it’s like the way that everything else— the human will to control— must ultimately humble itself to those mighty bodily forces. Clock time must bend to natural time in the beginning and in the end.

Another reading is that we made it, the orchid and I; we achieved this flower at the eleventh hour, at the very moment that the span of our cohabitation began to end, with the heart of the house— its library— being plucked out. (Not so light as that metaphor of plucking, of course— it will be sweaty lugging of boxes down the thirty stairs.)

How is a flower like a book? Poetry, symmetry. Petals, pages. Opening, closing. Meaningfully marked.

Here I moved boxes.

While I was writing about the orchid flower this morning I was trying to figure out how I could work in this recent Note about drawing quince blossom.

Flowers opening is the same, although the fragile pink-white moth-wing of the fruit blossom and the fleshy bright slices of the orchid are not the same. It seemed relevant, but I couldn’t make it fit. Then Kev said it was going to rain. I left off writing. He was right— farmer’s instinct: we finished packing the library boxes into the car just as the first drops fell.

When we arrived at Kev’s, he went straight to his garden. I followed, and there I saw that the first blossoms were opening on the gnarly old apple tree.

It’s evening, the other end of the day. (Charcoal-coloured cloud over the mountains, gold-lit green grass scattered with buttercups like yellow stars, the sound of peacocks calling. I open the window and call back to them, trying to lure them, imagining them appearing in the empty section, stalking like supermodels on their long strong legs, their ultramarine heads parting the grassy sea. Meow! Meow!)

My library is in storage, stacked in the corner of Kev’s spare room. Most of my last two decade’s work fits into four boxes— the right-hand stack.12

Paper pages are delicate as petals, but thousands of them weigh heavy. Accretion, like water making limestone drip by drip, layer by layer: stalagmites of my days.

(Update: I came home to this.)

Free time is a feeling; the spaciousness of the felt moment is a potent antidote to the time-is-money school of thought— to the overlordship of those who would have us count out every minute like a coin.

Robert Herrick

This piece that I wrote just after I moved in (though it pre-dates my orchid-phase) is about warmth and light and how humans are like plants:

Of Hopeful Green Stuff Woven

Heather Christle, The Crying Book: “Writing a poem is not so very different from digging a hole. It is work. You try to learn what you can from other holes and the people who dug before you. The difficulty comes from people who do not dig or spend time in holes thinking that the holes ought not to be so wet, or dark, or full of worms. ‘

I accidentally killed one of them (the one in the Orchid Hospital photo, it was awful) as told here:

The Force That Through the Green Fuse

Proverbs 16:18 Pride goeth before destruction, and an haughty spirit before a fall.

P.S. I learned by trial and error that Phalaenopsis prefer the tall, translucent pots; they don’t enjoy the squat, opaque ones so much.

This piece is mostly about a talk I attended about Antarctica, but I wrote about the orchid-dream in here:

Antarctica

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Left Hand of Darkness: “Sometimes as I am falling asleep in a dark, quiet room I have for a moment a great and treasurable illusion of the past. The wall of a tent leans up over my face, not visible but audible, a slanting plane of faint sound: the susurrus of blown snow. Nothing can be seen. The light-emission of the Chabe stove …

Well, permanent but only sometimes open, I guess…

Like I said, it was Winter, and Phalaenopsis can’t tolerate cold, but I kept the heat pump on— except for the time my landlady turned it off while I was away, which nearly killed the smallest orchid: its leaves shrivelled, but after a month or two it recovered.

This may seem like extravagant power-usage, but it was necessary to keep the house dry over Winter, so it was more like— if it’s going to be warm, then other living things might as well benefit from the warmth.

Again, I used photos of my houseplants to illustrate the post I wrote about losing my home:

Precariat Blues

Deborah Levy, Real Estate: “In fact I would be content to live in a humble wooden cabin on the edge of an ocean or a lake…”

Read her piece here: Getting Rid of Too Many Books: Ouch

Last night on The Long Table,

told how one time when he was moving house in London— in an earlier, more precarious life-stage— he decided to cull his books by half; and how once he had made that decision, it became easy to pick up a book and know in his gut whether it was for keeping or for throwing away.There was a time, not long ago (maybe ten years), when I could fit all my journals and drawing books into a single suitcase. I know because there was a bushfire in the hills up the Valley, and I packed the suitcase ready to grab and go if the fire came down. Coat, boots, mandolin; life’s work— at that point in time I could carry it in one hand.

A few days ago there was a sizable 5 a.m. earthquake (5.7): that reminded me of the time I was away from home when the Kaikoura earthquake (7.8) hit, a few minutes after midnight. (That was the biggest quake I’ve ever felt, and it went on and on, but I was sitting at the table playing my mandolin when it hit, so I stayed put, because I didn’t want to fall and damage my instrument.) Listening to National Radio, it seemed very likely that my house and everything in it would be obliterated by a tsunami.

There was also the time the bus I was on got diverted because there was a house fire in my suburb. Walking home, my body considered the possibility that my house was burnt and all my work lost. Matter is fragile; nothing is safe, really. Paper is particularly vulnerable, susceptible to water as well as fire. What’s in my head and hands, though— that’s my back-up.

I feel like your orchid is cheering you on in this trying time.

What you wrote about it being picked out by a stranger for a stranger and then dumped made me think of all the creatures we have turned into cheap tat from beautiful living beings. And how we treat them like paper tissues, destined for the garbage heap after a short flash of usefulness. A fleeting decoration.

When I got i to aquaristics I quickly got turned off by how greedy and destructive the hobby was in its widest form. The true afficionados split into two sections - those who would only buy locally bred to protect the original environments, and those that geeked out over the rarest fish and plants well knowing they are being ripped out of some place that used to be beautiful before we discovered this hobby. There’s also a lot of lying on where the plants come from, particularly slow growing ones like bucephalandra, so much easier to rip up old growth than to really run a nursery.

And the people who don’t get that involved…. It’s the poor sturdy goldfish or the betta rotting away in its sad little cup, cursed by endurance. In spite of that endurance they’re unlikely to last more than a few weeks, because people treat them like a colorful decoration and never think to learn about their needs. ‘It’s just a fish’.

I love the story of you and your orchid. You actually took the time to tame each other.

I love all this. I'm glad you kept your books. I still have tons. It's just as you say that they are connected to past writing and possible future writing. Thanks for the mention - delighted.