Penny Universities, Pepys' Perriwigg, and Daniel Defoe

On this day 360 years ago: (Verminous, Poxy) Restoration London

In the time of Covid lockdowns, I made a series of posts: extracts from Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year, with commentary,1 as a way of speaking slantwise to what we were collectively experiencing.2 (The mid-late 1600s was a gap in my historical knowledge. I learnt a lot by following little alleyways of whim.) Those flights of fancy pop up now as Memories on the Platform of the Damned, and some seem too good to let languish, so I’m upcycling them for Substack, altering the garment to fit.

(I’ve played that trick before, here:)

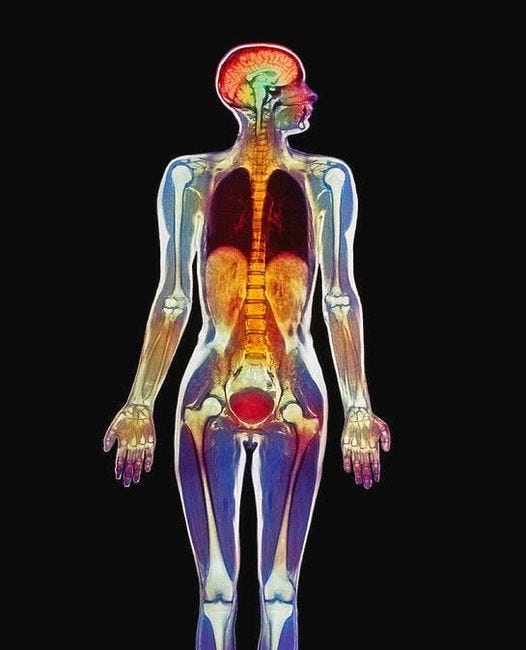

The City is a Body, You are a Group of Apes

Sideways History In October of 2021, deep into Covid Year Two, I was re-reading and publicly riffing on Daniel Defoe's A Journal of the Plague Year. A novel in the form of a diary, written in 1722, it is set in the time of the plague that devastated London in 1665, when Defoe himself was around four or five years old. (Surely that’s old enough to remembe…

Although Defoe’s novel takes the form of a journal, that’s a literary construct. Defoe was writing retrospectively in 1722,3 aged 62, about the Plague of 1664 - 1665, which he had experienced as a child of five; the book is written as if he were an adult living through it.

Samuel Pepys’ journal, however, is the real thing, an eye-witness account: six fat notebooks, written in code, covering the years 1660 to 1669. Pepys was the son of a London tailor, the fifth of eleven children. He lived through five reigns; he was a child during the Civil War, and as a teenager he witnessed the execution of Charles I. He worked for the Navy, but loved art, books, and the theatre. His great love was music. He had an ill-starred, tempestuous marriage, and no children. He was imprisoned three times, trying to ride the waves of change. (Successfully: he wasn’t executed.) His diaries— which weren’t published in full until 1976— are gossipy, personal, detailed, honest, and funny. (The entire Diary can be read here: https://www.pepysdiary.com/)

Michael Pollan points out in This is Your Mind on Plants that caffeine arrived in England in a single decade (the 1650s) in three different forms: coffee, tea, and chocolate.4 This spawned an intellectual explosion. Coffeehouses were known as penny universities. For the price of a coffee a person5 could access books, magazines, newspapers, pick up gossip and tips, and most importantly, listen in on the jazzed-up conversation of the greatest minds of the time. To appreciate the power of the coffeehouse, you have to understand that in the pub, one couldn't officially hang out with people outside of one’s own class. Rich people could slum it, but poor people couldn't do the reverse.6 The coffeehouse was (relatively) more egalitarian.7

Pollan: "London's coffeehouses were distinguished one from another by the professional or intellectual interests of their patrons... So, for example, merchants and men with interests in shipping gathered at Lloyd's Coffee House... [Which] eventually became the insurance brokerage Lloyd's of London. Similarly, the London Stock Exchange had its roots in the trades conducted at Jonathan's Coffee House.

Learned types and scientists... gathered at the Grecian, which became closely associated with the Royal Society; Isaac Newton and Edmund Halley debated physics and mathematics here, and supposedly once dissected a dolphin on the premises...

Meanwhile, the literary set gathered at Will's and at Button's, in Covent Garden... Some critics maintain that that the culture of the coffeehouse altered English prose in enduring ways. Habitués like Henry Fielding, Jonathan Swift, Daniel Defoe,8 and Laurence Sterne brought the rhythms of spoken English into their prose, marking a radical turn from the formality of previous English prose stylists."

I’d been thinking about Pepys anyway, because of my recent anaesthetic experience. In March 1658 Pepys underwent lithotomy: surgery to remove a bladder stone. Mark Jenner: “He was alive, sentient, and in agony when… the London surgeon Thomas Hollier tied him down, slid a probe up his penis, made a 3-inch (7.5 cm) incision between his scrotum and his anus, and pulled out a stone the size of a snooker ball.”

The stone had been debilitating for most of his life, but surgery was a very risky thing to do— with no sterilisation, the odds of dying were quite high, so it was brave / desperate of Pepys. Stitching wasn’t a thing yet, so the wound was left to drain and (hopefully) heal. Five weeks later, he was recovered. He had the stone mounted in gold and displayed in a special case, and marked the anniversary of his surgery with celebratory feasts.

An Historical Aside: Periwigs

This particular digression begins in late November 2021… At my friend Nigel's house, I spied a beautiful volume of Samuel Pepys' journals on the shelf. Plague being on my mind at the time, I cracked the book open to 1665. One particular passage took my fancy:

"Sunday 3 September 1665.

(Lord’s day). Up; and put on my coloured silk suit very fine, and my new periwigg, bought a good while since, but durst not wear, because the plague was in Westminster when I bought it; and it is a wonder what will be the fashion after the plague is done, as to periwiggs, for nobody will dare to buy any haire, for fear of the infection, that it had been cut off of the heads of people dead of the plague."

Men's wigs were big— both literally and figuratively— in the mid-1600s9 for a number of reasons: the baldness of the French King, Louis XIV; the greyness of the English King, Charles II; and rampant syphilis causing visible disfigurement, including hair loss. (Ah, syphilis… I like to subscribe to the Columbian Hypothesis— that syphilis was the revenge of the New World upon the Old, brought back to Europe in the 1490s by Columbus and co.)

The cost of a wig, made out of horse, goat, or human hair, ranged from about twenty-five shillings (a week's wages for the average Londoner), up to 800 shillings for the extremely wealthy. John Gay warns against organised wig-thievery in his 1716 poem Trivia, or the Art of Walking the Streets of London:

Nor is the wig with safety worn;

High on the shoulder, in a basket born

Lurks the small boy, whose hand to rapine bred,

Plucks off the curling humours of thy head.

One had to shave one's head to wear periwigs, because they got infested with lice. The wigs also got stinky, and had to be sent frequently to the barber to be cleaned, deloused, and— as fashions evolved— powdered.

Two years pre-Plague, in November of 1663,10 Pepys is having a fashion moment.

“Sunday 1st November 1663.

This morning my brother’s man brought me a new black baize waistecoate, faced with silke, which I put on from this day, laying by half-shirts for this winter. He brought me also my new gowne of purple shagg, trimmed with gold, very handsome; he also brought me as a gift from my brother, a velvet hat, very fine to ride in, and the fashion, which pleases me very well…”

The next day, Monday 2nd November, he hangs out with the King and the Duke of York— the King’s brother. “I heard the Duke say that he was going to wear a perriwigg; and they say the King also will. I never till this day observed that the King is mighty gray.”

In the evening Pepys goes to the wigmakers, but it’s too late in the day and the shop is shut: “Creed and I to the perriwigg makers, but it being dark concluded of nothing.” He goes home, has a fight with his wife, then they have make-up sex: “so as that though we went to bed with discontent she yielded to me and began to be fond, so that being willing myself to peace, we did before we sleep become very good friends, it being past 12 o’clock, and so with good hearts and joy to rest.”

The next day, he manages to get an appointment with a wig-maker.

"Tuesday 3rd November 1663.

By and by comes Chapman, the periwigg-maker, and upon my liking it, without more ado I went up, and there he cut off my haire, which went a little to my heart at present to part with it;11 but, it being over, and my periwigg on, I paid him 3l. for it; and away went he with my owne haire to make up another of, and I by and by, after I had caused all my mayds to look upon it; and they conclude it do become me; though Jane was mightily troubled for my parting of my own haire, and so was Besse, I went abroad to the Coffeehouse, and coming back went to Sir W. Pen and there sat with him and Captain Cocke till late at night... Sir W. Pen observed mightily, and discoursed much upon my cutting off my haire, as he do of every thing that concerns me,12 but it is over, and so I perceive after a day or two it will be no great matter."

Over the next few days he’s feeling self-conscious, but nobody seems that bothered.

Wednesday: “Up and to my office, shewing myself to Sir W. Batten, and Sir J. Minnes, and no great matter made of my periwigg, as I was afeard there would be.”

Sunday: “I found that my coming in a perriwigg did not prove so strange to the world as I was afear’d it would, for I thought that all the church would presently have cast their eyes all upon me, but I found no such thing.”

On Monday 9th of November, his fashion gamble pays off— the Duke thinks he’s cool: “so to the Duke, where, when we came into his closett, he told us that Mr. Pepys was so altered with his new perriwigg that he did not know him.”

On Wednesday the 11th he goes to see if his second wig is finished, but no joy: “it is not done.” Two days later the wig-maker comes over, with a wig made from Pepys’ cut-off hair.

"Friday 13th November 1663.

After dinner came my perriwigg-maker, and brings me a second periwigg, made of my own haire, which comes to 21s. 6d. more than the worth of my own haire, so that they both come to 4l. 1s. 6d., which he sayth will serve me two years, but I fear it."13

Four years later, after the Plague has died down and people aren't so terrified of dead people's hair any more, Pepys' prediction that the Plague would scare people off wig-wearing has proved incorrect.

"Wednesday 27th March 1667.14

I did go to the Swan, and there sent for Jervas, my old periwig maker, and he did bring me a periwig, but it was full of nits, so as I was troubled to see it (it being his old fault), and did send him to make it clean..."

Indeed, men’s wig-fashion lives on vestigially to this day, in the form of the white wigs that barristers still wear on ceremonial occasions.

Melville says in Moby Dick that a writer needs a big subject (i.e., big like a whale). “Give me a condor's quill! Give me Vesuvius' crater for an inkstand! Friends, hold my arms!… To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme. No great and enduring volume can ever be written on the flea, though many there be who have tried it.”

Flaubert, on the other hand, reckons that “Everything in art depends upon the execution: the story of a louse can be as beautiful as the story of Alexander the Great.”15 On that note, then, I’ll leave you with possibly the most famous work of kutu-literature, from Robbie Burns:

I bought the Penguin Classics edition. Although I’d read it some decades before, for the sake of posting I read only a few pages per day, then typed out passages from the book into the computer, choosing and pruning as I went, seeing what arose in response. It was an immersive, laborious experience; I felt like I was WRITING Defoe as much as reading him. I didn’t get to the end of the book before lockdown ended.

It was a good call, summoning echoes across history and letting myself be guided and prompted by Defoe. There’s a fair bit in the book that comes across as information-sharing: advice on decision-making, best practice etc. in Pandemic times. Defoe: “And here I may be able to make an Observation or two of my own, which may be of use hereafter to those, into whose Hands this may come, if they should ever see the like dreadful Visitation.”

Defoe also wrote four other books that year, including The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders.

From Arabia, India, and the Americas, respectively.

When I say a person, what I mean here is A MAN, because of course, NO GIRLS ALLOWED. (In England, that is; in France it was cool.) Women got shitty about this. Pamphlets were published saying that the coffeehouse culture was leading to sexual deprivation for womenfolk, to which the dudes responded that au contraire, "The Harmless and healing liquor [coffee] makes the Erection more Vigorous, the Ejaculation more full, [and] adds a spiritualescency to the Sperme." (LOL, OK mate...)

See, according to Bach, this is what happens when girls drink coffee: they stop listening to their Dads, and start macking on baristas.

Highrise it?

Because of this intellectual and social cross-pollination, coffeehouses were considered politically dangerous everywhere they flourished: across the Ottoman Empire, and across Europe. In France coffeehouses were hotbeds of the Revolution— the mob that stormed the Bastille in July of 1789 assembled beforehand in the Café de Foy.

Defoe writing caffeinated was a theory that made sense to me. It explained the hasty, rushing feeling of his prose. Sample sentence from Plague Year: "I heard of one infected Creature, who running out of his Bed in his Shirt, in the anguish and agony of his Swellings, of which he had three upon him, got his Shoes on and went to put on his Coat, but the Nurse resisting and snatching the Coat from him, he threw her down, run over her, run down Stairs and into the Street directly to the Thames in his Shirt, the Nurse running after him, and calling to the Watch to stop him; but the Watchmen frighted at the Man, and afraid to touch him, let him go on; upon which he ran down to the Still-yard Stairs, threw away his Shirt, and plung'd into the Thames, and, being a good swimmer, swam quite away over the River; and the Tide being coming in, as they call it, that is running West-ward, he reached the Land not till he came about the Falcon Stairs, where landing, and finding no People there, it being in the Night, he ran about the Streets there, Naked as he was, for a good while, when it being by that time High-water, he takes the River again, and swam back to the Still-yard, landed, ran up the Streets again to his own House, knocking at the Door, went up the Stairs, and into his bed again; and that this terrible Experiment cur'd him of the Plague, that is to say, that the violent Motion of his Arms and Legs stretch'd the Parts where the Swellings he had upon him were, that is to say under his Arms and his Groin, and caused them to ripen and break; and that the cold of the Water abated the Fever in his Blood.”

(This makes me feel better about my personal overuse of semicolons.)

When I posted about this sentence, Rebecca Solnit had just been writing about the Strunk and White school of literature that emphasises brevity as the supreme virtue; Omit needless words, the famous maxim. Solnit— a mistress of the digressive and sinuous— said by way of riposte: "a long sentence can sometimes weave together, modify, tease out the ambiguities, allow latitude for nuance, and give things the full complexity they deserve. A short sentence can be a walk to the fridge; a long sentence can be a pilgrimage in the night."

I tagged Solnit into my post on the Platform of the Damned, which she then shared— a high point in my literary career to date.

Note that in this passage, as in all Defoe, the nouns are capitalised. I’m a hater of the modern-day affectation for de-capitalising (one’s name, for instance— performative humility). The point of capital letters is to make the important words emerge from the field of prose, tall flowers above the grass, and I loved the way that in the Plague Year the names for Real Things were picked out this way without prejudice— Things were equal in their importance. I considered whether it would be possible for me to write like Defoe— to capitalise all nouns— but concluded that it would just as affected as those who de-capitalise, if not worse.

In all the Pepys I’ve quoted above, the only capitalised noun is Coffeehouse: but as Pepys was writing in code, this stylistic decision is likely down to the part of the interpreter.

And would remain so until the 1720s, when they got (slightly) smaller.

That is, 360 years ago this month.

Shaving one's head is indeed a drastic, irreversible feeling.

Sir William Penn is a frenemy of Pepys.

This is hard to parse. Does he fear the expense? Does he consider it a potential waste of money, if fashions change? Is he already scared of the Plague? Did he get interrupted mid-sentence?

Later this day he hears of his Mother’s death.

Another fun lice-fact: the proof that we once were kissing cousins with other species of hominin— aside from the Neanderthal DNA thing— is that humans carry parasite double-ups: slightly divergent sets of parasites (that is, ours, and someone else’s). This type of transfer is known— from the heirloom parasite’s point of view— as host-switching.

I so enjoyed meeting you in real life Rosie!! My writing twin hahah... haven't been able to read this yet as I'm in intense catch up mode, but saving to read later. HOpe to hang again soon. Nadine xx

Omg. Host switching is a concept I'm not going to forget.