Summoning Ned Ludd

I ham a friend of the pore and Distrest and a enemy to the opressers thron

PEACE AND A BIG LOAF

NO MACHENERY NO KING

(Wall slogans, Manchester, 1812)

Sheila Liming, Hanging Out; The Radical Power of Killing Time: “We must wrest time away from the places where it has been sequestered and kept from us against our will. We must work to seize and redistribute the wealth that is time, and, when we have done that, we must commit to the work of giving it all back to each other.”

Hear ye hear ye… I have never formally studied history— I am a purely self-taught, amateur historian. Learning history is something like learning how a car engine works. Not that history is like a car, it’s more like a world-sized ball of string— but what I mean is that knowledge is acquired piecemeal. The head gasket blows, you learn what the cylinder head is. The alternator craps out, you learn about the alternator. The brake pads need changing— & so on & so forth. What I’m trying to say is that if I’ve got anything wrong in this beast of a post, it’s entirely my own fault. (Historians, please feel free to weigh in with corrections in the comments section!) Also, there’s not enough room here to tell the whole tale of the Luddites. For a more comprehensive overview of how historical Luddism unfolded, as well as its relevance to our times, I recommend Brian Merchant’s entertaining & accessible book Blood in the Machine. Right, on with the yarn…

I saw a cartoon the other day that I can’t now find again.

Scene: Ancient Egypt. One person is whipping another.

The person being whipped says “I disapprove of this system.”

The person with the whip replies “Why are you participating in it, then?”

Six Propositions, Two Questions, & a Spell

Consent is only meaningful when refusal is possible.

If livelihood is contingent upon participation in a particular technology, the ability to refuse its use is kneecapped or nullified.

Creeping enshittification is social gaslighting en masse, which is why it feels like an abusive dynamic.

Time is a commons;

Public space is a commons;

Public time-space is a commons in the process of enclosure.

How to protect what is shared, felt, subtle? How to defend the beautiful unnameable commonality that is our human birthright?

Paying deep attention to specificity of place / culture is a hearty antidote to Big Tech’s stupefying suck.

Luddism / Neo-Luddism is an active defence of the social fabric.

I hereby grant you the power to resist or refuse any given technology. Hold your hand up to the screen, device, or other interface in a strong gesture of refusal, & speak aloud the following phrase:

I banish thee, demon, in the name of Ludd!

Call Yourself a Luddite?

Last week I promised a deep dive on Ned Ludd, Luddites & Luddism. Luddite is a term that’s thrown around a lot these days, mostly as an insult, sometimes as a semi-ironic self-identifier. (It’s me: I frequently call myself a Luddite, have done for years.)

As Richard Byrne wrote way back in 2013: “In the straitened and highly ritualized discourse of tech boosterism, ‘Luddite’ has become a catchall dirty word for anything that stands in its way. The specter of Luddism is raised and stigmatized again and again as a crank persuasion… Any reflexive tendency toward criticism, or skepticism about the aims of our confident new digital elite, must be equated with the doomed rebellion of the first generation of English industrial workers.”1

Yet, despite its clear parallels with the moment we find ourselves in, historical Luddism is poorly understood. That’s partly because it’s hard to make any definitive statements about Luddism— by its very nature a secretive, collective, local phenomenon. Byrne again: “One of the most notorious features of Luddism was the movement’s secret oaths. And those vows largely held. No Luddite leader ever wrote a memoir. Nor did any convicted Luddite offer confessions on the gallows. Even those outside the movement in a position to know its secrets rarely, if ever, spoke up.”

However, the blanket modern-day misunderstanding / mischaracterisation of Luddites as technophobic primitives is also down to the fact that Luddism is suppressed radical history. Mockery is an effective form of propaganda (as the Luddites themselves well knew).

As Inigo Laguda put it recently: “i ask you: who benefits from reducing ‘luddites’ to ignorant savages who just can’t stand technology?

who benefits from stripping away their radical motivations?…

you have to be alert when words you’ve never thought about are being wielded in a way that’s suspicious and you have to be curious enough to seek out the origin of them.”2

The thing about studying history is that while you may start by pulling a single thread, no historical act happens in isolation. You pull more threads, trying to understand the social fabric; soon enough you’re seeing the cut of the garment, then eventually you find you’re twisted in.

Come Cropper Lads of High Renown

I’ve been singing Luddite songs again lately. If I unspool the thread of song-causality, maybe my Luddite leanings started with this one, many decades ago— The World Turned Upside Down, a song about the Diggers or True Levellers, here sung & played by noted Communist Dick Gaughan:3

This song, although it closely references The True Levellers Standard Advanced (Gerrard Winstanley’s 1649 pamphlet),4 is modern, written by Leon Rosselson in 1975. As soon as I worked out this song was new, not old, I started wondering if there were any contemporary Digger songs from the 1640s. The answer was yes. Here is an abridged but otherwise faithful rendition of The Diggers’ Song, sung by Chumbawumba:

When it comes to songs concerning historical events, I’m always more interested in what people have to say for themselves, rather than what others have to say about them. That is, it’s one thing to sing a song somebody wrote later about a given topic, time, or movement; quite another to sing the songs the people themselves made & sang while that time or movement was going on.

For an extreme example of what I’m talking about, consider war songs. The songs written about a given war by people who weren’t there— either because they were removed in space (i.e. at home / not soldiers), or time (written when the war is over), or both— tend to be sentimental, grandiose, glorifying, & / or gratuitous; whereas those the soldiers themselves sang tend towards rhythmic (because marching), humorous, lewd, ruthless, & generally piss-takey.

Anyway, after singing the Diggers song for a number of years, I got to wondering about songs associated with other radical movements. I think I first found this Luddite song on a CD from the big old Wellington library— my former musical hunting grounds:

This is a genuine Luddite song, & it comes with a tune, ‘Poor Jack’.5 However, I prefer Boulter’s tune. His delivery is quite gentle, but add a bit of guts & this tune stands up well to acapella singing. A few weeks back I brought this song out at a singing session, & it irked certain people who like to sing about whores & their wife being the devil & things of that nature, so then I thought I would hunt out more Luddite songs. I soon found Our Subversive Voice, a list of radical songs, & there I found Cropper Lads (which I half-knew already, because my friends Ian & Jean sing it in their band Celtic Ferret):

What a belter! (Great Enoch refers to the hammer, named after the blacksmith who made it.) Even though the Folly Bridge version is word for word the original song, I prefer to tweak the chorus a little to vary the line endings, thus—

The cropper lads for me,

And gallant lads they be,

Who with lusty stroke

The shear-frames broke,

The cropper lads for me.

When I told Kev that Cropper Lads was from Huddersfield, he said “I’ve been there.”

Me: “What were you doing there?”

Kev: “Working at mill. Learning to weave on a Dobcross loom. Somewhere in the garage there’s a moth-eaten old flat cap made from cloth I wove.”

Those two Luddite songs— General Ludd’s Triumph & Cropper Lads— represent two different iterations of Luddism. General Ludd’s Triumph, dated January 1812, is from Nottinghamshire. It name-drops Robin Hood & specifies that Ludd’s violence is directed against things, not people. Cropper Lads is from Huddersfield in Yorkshire, a mere month later but far more militant— With hatchet, pike, & gun. The Frame-Breaking Act was passed that same month (February of 1812), making Luddism a hanging offence: the situation was intensifying quickly.

These songs were written by Luddites for Luddites. A few other Luddite songs survive (there’s one about a loaf of bread, Hunting the Loaf; another about tyrants of England, The Hand-Loom Weaver’s Lament, which my friend Jenn sings)— but only those few, though I’ve no doubt there were more songs that went unrecorded. Luddism was necessarily a secretive business, for the aforementioned reason that it could get you killed by the state.

I find it interesting, though, that from my point of view, singing them 200 years later, these songs function as a package or letter sent from history. There is a great deal of very specific cultural meaning folded into a folk song. As I’ve learnt more about Luddite history, certain lines in the songs have unfolded their meaning to me further, such as the final line of General Ludd’s Triumph:

And colting, and cutting, and squaring no more

Shall deprive honest workmen of bread.

Colting: the practice of employing workers who hadn’t completed their apprenticeship.

Cutting: weaving flat cloth & cutting pieces out of it, rather than weaving stockings in the round— considered to result in an inferior product.

Squaring: this is to do with tuning the loom— squaring is tightening the needles. In the origin myth of Luddism, this is what the apprentice Ned Ludd was told to do, right before he smashed his machine in anger. (My guess is that here the term is being used metaphorically, but I’m not 100% certain.)

I always liked the sounds of those words together— colting & cutting & squaring: as in many weaving songs, they make a work-like rhythm— but now I understand that in terms of meaning, this line is a condemnation of a set of specific corner-cutting business practices that save time & boost profits for the owners, but lower quality & drive down wages for the workers.

Who is Ned Ludd?

He’s that wrathful prentice stocking-weaver who first smashed his machine with a hammer, right?6 Then… how is he also a Captain, or even a General? Is he somehow his own Dad? Does he live in Sherwood Forest, like Robin Hood?7 Is he related to the King spoken of by that great olden-day bullshit-artist Geoffrey of Monmouth? Why does he wear a dress? (More on that in a bit.) Is Ludd a Lady, or a gang of wives? Is our Ned, in fact, a girl named Eliza?

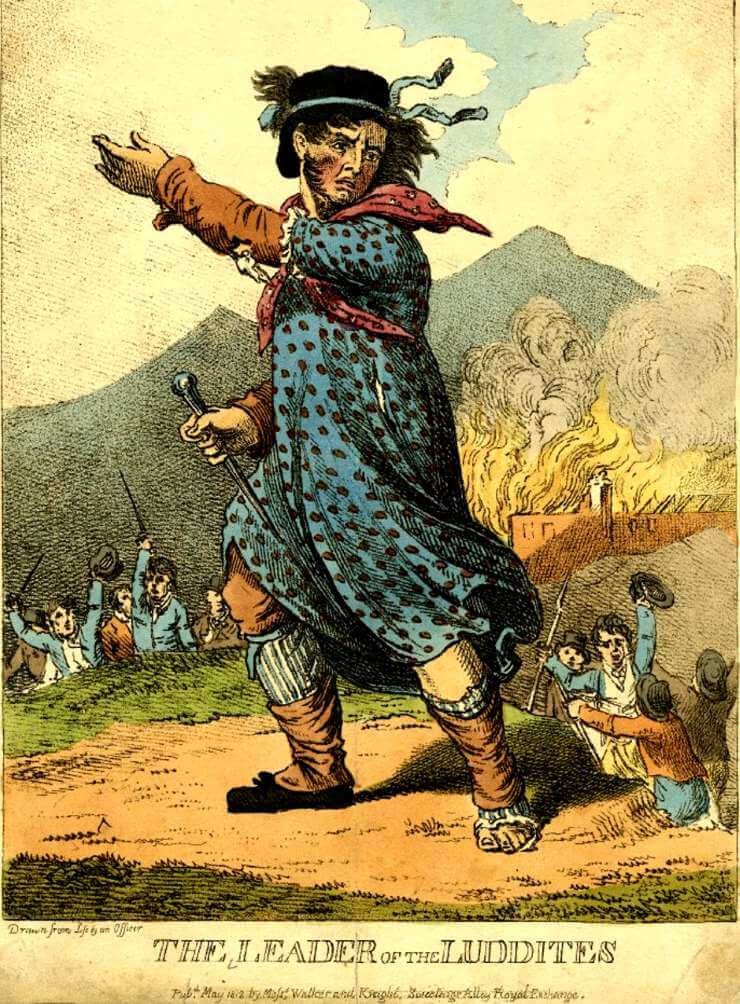

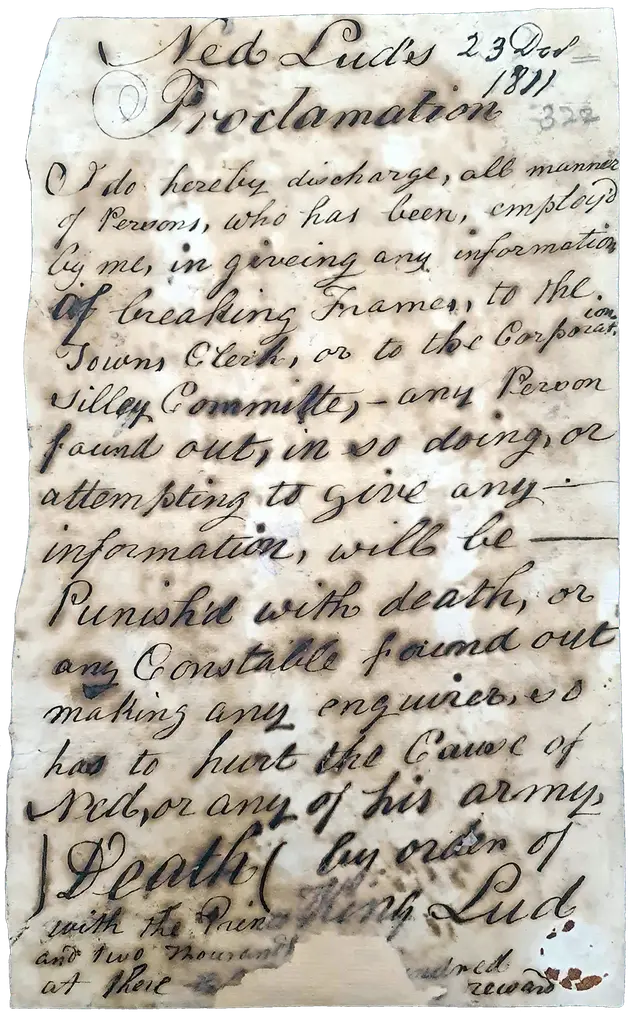

This image is the only visual representation of Ned Ludd— or at least, the one that’s repeated over & over again on the internet— so I want to consider it further. Firstly, it’s important to note that the caption does not directly name Ned Ludd as the subject: what it actually says is THE LEADER OF THE LUDDITES. (In my view the refusal to name Ludd is a magical decision: more on that in a bit.)

This image feels opaque to me, semi-unreadable. As with many artefacts from the past, it makes me feel that I am looking with dumb modern eyes.8 Is it a newspaper, a pamphlet? Satirical cartoons were big in Georgian times. There are messages & meanings here for the intended audience, which is not me. Who is it for, then? Is it supportive of the Luddites, or mocking, or both?

The mob in the background are waving sticks, pikes, & hats, & there is a building on fire, presumably a factory or factory-owner’s mansion. The chunky figure strikes a heroic pose, with the wind flattening his side-whiskers to his face like a— yes— like a General in a painting— Napoleon on a rearing horse, say, with the Alpine peaks behind him: yet what he is riding is a stick, a cudgel of some sort (implying violence). A tension, then, between the heroic affect & the enactment of peasantish thuggery? He is also kind of ridiculous, in the ribboned bonnet, neckerchief, & spotted dress that he has thrown on over his everyday clothes. He has a tear in his sleeve, he has lost a garter & one shoe, & his stockings are worn through at the toe.

His left foot, in fact, is foregrounded & rendered prominent in the image, the lowest point of the diagonal formed by his upraised gesturing hand & the folds of his dress. The point of the naked foot, as I read it, is that those who make the clothes cannot afford to wear the clothes: it was the stockingers who kicked Luddism off in the first place. That makes me think of two things. It reminds me of the words to the song Four Loom Weaver (AKA The Poor Cotton Weaver):9 “Me clogs are both brokken an’ stockins aw’ve none. Yo’d hardly gie tuppence for all aw’ve got on.”

One further point about the stockings. Striped stockings for men were, at this point, a very outdated fashion— they had been big in the 1780s / 1790s.10 But it may be that the artist liked the graphic look of them, & it doesn’t mean any more than that. (Steal his look here: Samson Historical - Striped Cotton Stocking.) Speaking of fashionability, due to the French Revolution-inspired trouser-craze, men’s stockings were about to go the way of the dinosaurs… A not insignificant fact if your trade was stocking-manufacture.

The other thing that half-naked foot makes me think of is a video I saw once where someone went to the Ivory Coast & gave some chocolate to the people growing & processing the cocoa pods into beans, who had never tasted chocolate.11

From then, to now: What you produce is not for the likes of you.

Squinting at the tiny writing along the bottom, I make out the inscription: Drawn from Life by an Officer. This is as close as you could get to a snapshot back in the day. Someone— ‘an Officer’— has witnessed this scene, then drawn it from memory, then the engraver has rendered it reproducible. (Or that’s the conceit, at least.) Right along the bottom it reads: ‘Pub.d May 1812 by Mssrs Walker and Knight, Sweetings Alley, Royal Exchange’. The British Museum tells me that E. Walker & S. Knight worked out of 3 Sweetings Alley, Royal Exchange, Cornhill, London. They were publishers, making this a print— a hand-coloured etching. The artist is likely, then, some anonymous jobbing engraver.

This image was made in May 1812— that is, a year into the mass outbreak of machine-breaking / Luddism, which had spread from Nottinghamshire (stockings) to Yorkshire (wool) & Lancashire (cotton).

In Mid-February, the Destruction of Stocking-Frames etc. Act 1812 (AKA the Frame-Breaking Act) had been rushed through Parliament, making the swearing of Luddite oaths punishable by transportation, & machine-wrecking punishable by death.12

Also in May 1812, on the 11th, punitively anti-radical Prime Minister Spencer Perceval was assassinated, shot dead in the House of Commons— not by the Luddites, it turns out, though they have been threatening to kill him for some time, but by disgruntled Liverpool merchant John Bellingham, released from Russian prison a year & a half earlier.13 Thus it is a volatile moment indeed that this fiery image depicts.

Why Luddite Smash?

Mention the word Luddite, & the one thing most people know is that Luddites broke machines. Workers, rather than operating machines, smash them up with hammers: a symbolically potent action, a idea that reverberates down the centuries. But why did they do it? Reduced down to a meme, machine-breaking seems like simple sabotage, but the circumstances were complex. Luddism is a phenomenon that arose in a particular historical context.

Kevin Binfield, in his excellent & comprehensive book The Writings of the Luddites, characterises Luddite concerns thus: “[The] aims and methods [of the Luddites] are understood in terms of protests against hiring practices that resulted in the abatement of wages, increases in rents of machines used to produce or finish cloth, the use of machines that damaged a trade’s reputation for quality, increases in the costs of provisions, and the denial of a political voice to those persons affected by the decline in wages and the increase in prices.”14

Firstly, machine-breaking was not a novel tactic of dissent. By the early 1800s, machine-breaking was a long-established practice: Eric Hobsbawm, who calls it ‘collective bargaining by riot’, says it began in the Restoration, i.e. around 1660: “Machine-breaking in general… begins as a serious phenomenon (if it can be properly said to have a beginning) some time in the seventeenth century and continues until roughly 1830.”15

Secondly, machine-smashing was not a simple matter of being Neanderthally angry at newfangled machines. The technology used by the stockingers of Nottinghamshire— the original Luddites— was not new: the stocking-frame had been invented over 200 years earlier. (Neither was the breaking of machinery indiscriminate. Even within a single workshop, certain machines were smashed & certain others left alone— his wrath is entirely confined to wide frames, as it says in the song.)

Basically, it was not technology per se to which the Luddites objected. Rather, they revolted against the economic structures that were driving them & their families steadily into deeper & deeper destitution. That is, contrary to the popular myth, it was not technophobia that drove them to violence (against inanimate objects (& eventually against people), but outrage at economic injustice. The Luddites began by attempted negotiation, then progressed to removing machine parts. Then they sent threatening letters. Only after these tactics failed did they escalate to precisely targetted industrial sabotage.

Brian Merchant describes the Luddite outbreak of November 1811: “The machine breakers had prepared for this uprising; they were organized, strategic, and intentional in their displays of power. Those quiet months over the summer had evidently been put to productive use. ‘The practice of these men was to assemble in parties from six to sixty, according as circumstances required, under a supposed leader… who had the absolute command of them, and directed their operations; placing the guards, who were armed with swords, firelocks, etc. in their proper places, while those armed with hammers, axes, &c. were ordered to enter the house & demolish the frames,’ wrote the Nottingham Review journalist John Blackner, ‘and when the work of mischief was completed, he called over the list of his men, who answered to a particular number, and then he gave a signal for their departure by discharging a pistol, which implied that all was right.’

The leader of each of these parties went by the same name: General Ludd.”

Tipping Points

Why did tensions come to a head when they did— in Nottinghamshire, in late Winter, February of 1811? (This was just the beginning of the Luddite outbreak, which morphed as it spread.)16 Some broad contextual points to note:

The Napoleonic Wars had been grinding on for eight years. Napoleon was trying to end Britain’s stranglehold on Europe by means of economic blockade: in 1806 Napoleon had organised European nations into the Continental System, to blockade British trade.17 Ultimately this didn’t really work, but Britain, meanwhile, was pouring money & soldiers into the wars with France (including by financing foreign armies). War with America was also brewing, with an attendant shutdown on trade. These twin problems had an ongoing effect on quality of life for the British populace. Higher taxes, rising food prices—by 1812 there would be widespread food riots— depressed trade, & falling wages: the wages of Nottingham weavers had fallen by an estimated minimum of 30%. (It is also interesting to note that war veterans were among the Luddites.)18

The French Revolution had just occurred (1789 - 99). Witnessing the Revolution added fuel to the fire of radical sentiments in Britain. It happened there, why not here? This made the British authorities very jumpy, which led to extremely harsh crackdowns on civil unrest. This contemporary song, sung by Jennifer Reid (to the tune of God Save the King, or as the original broadside has it, ‘Bob Shave a King’) extols the virtues of the guillotine:

Speaking of the French Revolution, trousers were an identifier of the French Revolutionary, the term sans-culotte meaning ‘without breeches’. That is, the aristocracy wore knee-breeches & stockings, but the working classes of France wore trousers to the ankle. The British peasantry had also been wearing knee-breeches & stockings for the last couple of centuries. However, the time of breeches was waning, the time of trousers was dawning… bad luck for stocking manufacturers.

The King, George III, known scornfully as ‘Farmer George’ for his interest in agriculture, had finally gone totally insane (though he’d been mad on & off for a number of decades) & had been replaced on the throne by his son, acting as Prince Regent. Because the King was still technically alive, the Prince could only become Prince Regent (i.e. act in the King’s stead) by legislation passed without the King’s consent. This legislation— the Care of King During his Illness, etc. Act— was passed on the 5th of February 1811. The old King had been mad, but the Prince Regent was a tubby flibbertigibbet who did not much care to attend to affairs of state: he preferred dressing up, snacks, & mistresses.19 Also, the Prince Regent was too lazy to overturn the reactionary Government his Tory Dad had left in place, which leads us to…

The soon-to-be-assassinated Prime Minister, Spencer Perceval, was a harsh anti-radical. (These sentiments were not universal among the ruling class: some politicians were more sensitive to the suffering of common people.)

As I have said, the OG Luddites— the ones who first kicked off— were stockingers. They wove stockings, in their homes or in small workshops. However, they worked on rented machines, under the oversight of so-called ‘master hosiers’, who supplied them with raw material as well as machinery. Some master hosiers had begun paying workers in ‘truck’— that is, paying them in materials rather than money. Other new practices the Luddites objected to included ‘colting’, or employing workers who had not completed an apprenticeship; & the use of ‘wide frames’— producing a flat piece of cloth & stitching stockings out of it. This was considered to produce an inferior product, & it was felt that the master hosiers were bringing the trade into disrepute.

The stocking trade had been moved from London to Nottingham in 1728 to evade the influence of the London Guild The Worshipful Company of Framework Knitters.

Also, the Combination Acts of 1799 & 1800 had made Unionism effectively illegal (this was an attempt to crack down on the Jacobins): three months in jail or up to two months’ hard labour for any workingman who combined with another to gain an increase in wages or a decrease in hours, or who solicited anyone else to leave work, or objected to working with any other workman.

So— these two aforementioned factors had stripped away the protection of firstly, the Guild, & secondly, the power to legally unionise. In Nottingham, a two-decade-long price-for-work agreement had ended in 1807. In West Yorkshire, the statute prohibiting use of the gig mill had lapsed in 1809, & with it trade protection for the croppers. In some towns, up to half the population was unemployed.20

Meanwhile, influenced by the relatively recent writings of Adam Smith & Thomas Malthus (Basically ‘Yay industrial capitalism! / Suck it, peasants’), the rise of the Factory Age had begun. In Lancashire & Yorkshire, whole towns had grown up to provide labour to the factories. People worked in these dangerous, often-fatal places under what we would consider slave labour conditions. Orphaned children, for instance, worked 14 hours a day, six days a week, beaten, starved, frequently maimed or even killed. Brian Merchant says that “twenty thousand children worked in the cotton industry alone.”

In combination with the trade blockades, two bad harvests in a row meant that poor people were hungry, even starving. In 1812 the price of corn was to reach a 100-year high. This was the context in which profiteering became intolerable.

Brian Merchant: “There was no reason for anyone to starve; the factory owners were still turning profits. If they stopped running new machines, there would be more work to go around. Besides, to the artisans who had taken seriously the traditions and contracts of their trade, using machinery to take market share at the cost of the worker was neither moral nor fair. It infuriated them that the entrepreneurs and factory owners claimed the right to automate people’s work, when it so obviously led to suffering.”

Z.M.L. of Librarian Shipwreck puts it this way: “As for the question of what the Luddites wanted, or what the world would look like if the Luddites had been able to ‘have their way’? Frankly, the Luddites wanted to be able to feed their children, they didn’t want to be driven into poverty, and they thought those things were more important than the factory owners becoming wealthier and more powerful. There is nothing particularly radical or incomprehensible about such desires.”

A Side-Note: Ned Ludd / Ned Kelly

Kevin Binfield says that “Luddite rhetoric is transgressive, mutant, and hybridizing.” Reading the Luddite’s writings, it was clear that the writers ranged from semi-literate to literate. (Authorities feared, in particular, the combination of radicalism & literacy.)

A likeness was nagging at me: these letters reminded me of something. It didn’t take me long to work it out. The tone of the Luddite letters reminded me of another Ned— Ned Kelly, in the famous Jerilderie letter, written in February of 1879 when Kelly & his gang were on the run, robbing banks & hiding out. Why did the Luddite letters remind me of Kelly? I could see immediately— it was the tone, a particular blend of grandiosity & piss-taking. Kelly, too, switches between mockery & hellfire.

Compare & contrast:

The Jerilderie letter ends with these mighty words: “I am a widows son outlawed and my orders must be obeyed.”

An anonymous Luddite letter of 7 February 1812 ends: “I ham a friend of the pore and Distrest and a enemy to the opressers thron (signed) GENERAL LUD”

Another tonal similarity that strikes me is that— like Kelly’s letter— the Luddite letters are collaborative works. It’s thought Ned Kelly dictated the Jerilderie letter to Joe Byrne, & you can see that collaborativeness in the text— you can see them whiling away the hours & days in hiding as they worked on this fifty-page document. “Write, a parcel of big ugly fat-necked wombat headed big bellied magpie legged narrow hipped splaw-footed sons of Irish Bailiffs or english landlords which is better known as Officers of Justice or Victorian Police who some calls honest gentlemen, LOLOLOL”

The reason for the defiant tone is also comparable. Both Kelly & the Luddites were trapped in poverty & driven to desperate acts by intractably unfair systems. Once serious crimes had been committed— injury then murder of police officers in Kelly’s case; whereas in the case of the Luddites, mere frame-breaking was a hanging offence, remember— you might as well be hung for a sheep as for a lamb. You’re already in too deep, so you might as well say exactly what you mean. Hence the tone of these outlaw communiqués.

The Folk Practice of Cross-Dressing

Peter Carey channelled the voice of the Jerilderie letter into his Booker-winning masterpiece True History of the Kelly Gang, a book I’ve read many, many times. It’s a work of true genius, half-history & half-speculation, one of my all-time favourite novels, a book I try to make everyone read. The other immediate link I saw between the Luddites & Ned Kelly was Carey’s plot device, the Sons of Sieve— dress-wearing Irish rebels. (Kelly finds his Father’s dress & burns it; later the gang wear dresses in emulation of their Irish forefathers. The Irish-born Mary Hearn tells the Kelly-gang boys that they have no idea what they’re playing at, that they’re colonials with heads full of romance who know nothing of the Old Country. But what choice do they have, green sprigs grown from root-severed stems? By which I mean, also me & mine.)

In this fairly accurate film, made in the dark middle of the Thatcher years & based on true historical events (the murder of Yorkshire mill owner William Horsfall in April 1812), we can see Luddite cross-dressing & face-painting from 27.10:

What does a man in a dress signify? Cross-dressing is a trickster-sign, a marker of the collapse of categories & distinctions, a shape-shifting signifier of the upside-down. Normal rules are suspended. It’s also a sign of magic. Wearing dresses & smearing one’s face with soot are both ancient folk practices of the U.K., seen still in traditional forms such as Mummers Plays. (Despite the superficial resemblance— blackening the face— this tradition has nothing to do with American blackface. Soot & ash are readily available, disguise a person, & make them look scary. Nevertheless, many modern Morris dancing sides have adapted this ancient tradition in creative ways, as seen here in this dance by Beltane Border Morris):

Kelly, though heavily posthumously mythologised, was real; Ludd is not real. Or at least, they’re not the same kind of real. Kelly was flesh & blood, whereas Ludd is more like Hood, like Robin— one of those slippery figures who hangs around at the edge of civilisation. Culture-hero, trickster, demigod, somewhere in those realms. And here we come to the heart of the matter.

Adrian Randall: “Previous labor struggles had failed to give rise to a name or an emblem that stuck. Those involved had rarely given themselves a title and were generically labeled by the authorities simply as ‘depradators,’ ‘the disaffected,’ or, more frequently, ‘the mob.’ Yet the machine breakers of 1811–12 were referred to almost from the start as ‘Luddites,’ the name they gave themselves.”

Where did Ludd come from? Unlike Robin Hood (or King Arthur, for that matter), he was brought forth in the soot & sweat of the modern age, not distilled from the mythological mists of the pre-literate past. Spawned by a culture under pressure, Ned Ludd arose in response to a need. Once named, he gave his name back to those who named him, to empower the disempowered. He became a tool of thought. Folk magic in action.

Twisting In

Twisting in = swearing Luddite oaths, as seen in the film. Brian Merchant explains that as well as swearing to secrecy, oath-taking could mean vows “to bind oneself to never work the machines hurtful to commonality, and never to work in a shop or factory where such machines were deployed.”

I mention twisting in to Kev, because the phrase caught my ear. Twisting in, says Kev, is when the warp thread ends & a new one is joined onto it: he saw it done in the mill. The two loose ends are twisted together, then the joined ends are twisted back into the main thread. The thread is then, of course, woven into the cloth, where it becomes virtually invisible. Twisting in was done by men, who were in charge of the warp. Their fingers would be coated with soluble oil, & the act of twisting in was very quick, almost unnoticeable— a tiny swift rubbing of thumb & forefinger.

Before twisting in: you are a loose thread. After twisting in: you are inextricably woven into the cloth. It’s a one-way process— you are the fabric now.

Behind the Cloud

My underwear: made in Bangladesh. My jeans: made in China.21 My bra: made in China. My singlet: made in China. My shirt: made in China. My jacket: made in China, but (I think) modified in Wellington— NZ Army buttons sewn on. My socks & scarf: unlabelled.

Everything came from the op shop / dump shop. If I estimate how much I spent on these garments, the sum total is likely around $100. My boots: made in Dunedin, NZ. (The boots cost three times more than everything else put together.)

When people play the imaginative game if you won the lottery, what would you spend it on? I immediately think of finery— of gold, boots, bespoke coats— an improved, more glorious form of Wizardwear. (There’s a strong sense in which a Wizard is what she wears.) Then after that, I think about how great it would be to split the money & distribute it to all my people. That’s all very Leoish (personal glory & overflowing generosity), but it’s also kind of sad that my imagination is uncomfortable with stretching too far beyond a fancier variant of my current reality. Travel— theoretically, why not? A beautiful apartment— sure, I guess? But my life’s discipline has been to seek abundance in simplicity & I find it hard to imagine surplus.

I have been thinking about that process of mechanisation & specialisation to the nth degree that we could call ‘Industry’ or ‘Capitalism’ (& isn’t it all there in that name? Industry means a certain kind of labour, implying virtue through work, but Capitalism means we worship money as a separate God, above all)— anyway, I have been thinking that the separation between me, the person who wears the clothes, & the worker who made the clothes I wear is like a wall of fog. It is possible, with effort, to remember & understand that there are people on the other side of that wall of fog, who wove the cloth that makes up these clothes I wear; there are people whose hands worked the machines that cut & stitched them together, but they may as well be on the moon.22 Their life is labour & mine is consumption. Even though by some ways of looking I’m in an underclass, still I am fed & clothed.

So far, so Industrial. If I try to think about clothing at the other extreme, I remember Caroline Ross talking the other week about ‘bog fashion’, the clothes preserved on the bodies of bog mummies across Europe by the anaerobic peat. In the Bronze Age & Iron Age every thread of every garment was woven by hand; every garment was the result of hundreds of hours of labour, & this labour of spinning & weaving would have been visible, near-constant, done by every women in every spare moment. A Bronze Age garment is so far removed from a modern fast-fashion garment that they cannot even really be said to be the same species of animal.

I am trying to articulate something here about visible vs. invisible labour. In the minority / Western world, where I live, we are constantly shown products, surfaces, outcomes; & we are discouraged from thinking about processes, origins, beginnings & ends. We inhabit a perpetual middle, the bit where the food gets eaten. Not the cooking, not the dishes, let alone the growing or composting. This state of ignorance is a form of infantilism. Consuming without making.

I keep thinking about this blog post from Z.M.L of Librarian Shipwreck, “Technology in the Present Tense” – Notes from a Weary Luddite. They say: “When we talk about technology it is important to figure out which ‘we’ it is that is being foregrounded. The lifecycle of a technology involves many different people in a range of varied locations who move in and out of the ‘we’ that is generally involved in technology. From those who mine rare-earth minerals, to those at various stages of the supply chains, to workers in factory’s assembling devices, to clerks in stores selling those devices, to actual users, to tech designers in sunny Californian campuses, to refurbishers, to e-waste recyclers, and so on and so forth—the ‘we’ of any given technology is not so simple a thing to define.”23

(As Tonto said to the Lone Ranger— What do you mean ‘we’, white man?)

Given that I seem to be becoming more animist, not less, as I get older, objects carry weight beyond the economic. Say a company moves production overseas. The ‘product’ may appear the same, but it is not the same. Economically / energetically, its resonance changes when we know it is made by slaves but we buy it anyway. This arrangement— wherein ordinary people survive by the use & consumption of things they do not see being made or produced— is a very recent scenario, historically. It’s not what we’re adapted to, & as animals, I reckon it makes us uneasy.

Seeing the life of an object through time requires engagement with the gnarly responsibility of being an animal who must consume in order to live. It is impossible to be a modern, minority-world human being with clean hands. We all must dance with the devil daily. Z.M.L. again: “To truly ‘perceive technology’ it is necessary to ask what it is that is being perceived. Often, it’s a finished product, that came in a fancy box, that we plugged in, and started to use, and that is how it gets perceived. It is harder to look at a particular gadget and see all of the minerals that make it up, hard to see all of the international supply chains that were involved in this device reaching us, hard to see the faces of the workers who put this together...” Our bodies know, on an intuitive / magical level, what lies beyond the wall of fog: other bodies, who touch us through their work.

This paradigm— what is consumed— has changed even in my own lifetime. When I was a kid, many things were made here but also, there were fewer kinds of things. My parents would make a special trip into the city to buy tofu & soy sauce for their brown rice from Wah Lee's. Then there was a time of Buy New Zealand Made: I remember the little kiwi logo, red & blue, affixed to products. I look it up & discover the Buy NZ Made campaign launched in 1988— that is, right when the policies of the disastrously Neoliberal 1984 Lange Government were really starting to bite.24 That is, this campaign was a countermeasure. First campaign slogan: Buy New Zealand Made & Keep Your Country Working. According to the Buy New Zealand Made website, 87% of Kiwis ‘often consider whether a product is NZ made’, & 92% of Kiwis ‘seek out ethically manufactured goods’.

Handcraft as Anti-Tech Activity

The only handmade garments you see people wearing these days are likely to be knitted or crocheted (usually from bought wool, but still, there’s a lot of labour involved in the construction of a knitted jumper, say). In recent years I have noticed a handcraft revival among young people. Knitting, crochet, embroidery, even weaving, by one eccentric who carries around a small loom. I understand the pleasures of craft, yet this small, localised stitchcraft revival gave me a weirdly ambivalent feeling. This feeling was something to do with the genderedness of the practice: it seemed to be predominantly young women practicing these time-consuming crafts in public. I was reacting, I think, to what seemed like a virtuous demonstration of traditional femininity—the performance of women’s work.25 Then someone told me that this is an anti-smartphone practice; keeping the hands constructively busy & the mind attentive to the material world.

I’ve written before about the common origin-word of text & textile— both come from the Latin texere, to weave;26 from the Proto-Indo-European *teks-, also meaning to weave or fabricate. (Fabricate...) Is a pen like a needle? Writing seems to me more like knitting than weaving, in that a single line, by patterning, makes a garment. The action happens at the metal point of the tool. There is a similarity in practice, too, which is this: repetitive small action in service of usefulness.

Fellow Hinge-Dwellers

Luddism, viewed in historical hindsight, is a phenomenon that happened at a historical hinge point: the death of cottage industry / the birth of the factory. The Industrial Revolution, we call it from here— the dawn of the absolute dominion of the clock over human life, the human body worked as a tiny part of a big machine. So to us futurefolks Luddism means something like ‘the symbolic rebellion of people who did not want to become that tiny machine part’. There is some truth to that interpretation, but it was impossible for the Luddites themselves to see how history would play out: they were responding to the moment. Symbolic interpretation is the privilege of hindsight. One main driver for Luddism, as far as I can tell, was literal hunger— A Big Loaf or No King. One lesson history offers is that extreme economic disparity is a precursor to violence. That’s not a ‘political’ interpretation, just a fact, & it’s one reason for the emergence of the welfare state, as I’ve said before: keeping the very poorest from revolution-level desperation.

Indeed, there is something here about fairness & unfairness. The social fabric is woven & held in place by rules & laws. It was ever thus, since before we were human. The Social Contract, as I understand it, proposes that individual humans submit to laws & limitations (i.e. surrender certain individual freedoms) in exchange for— broadly— stability, order, & prosperity. We are now in a time of widespread dissolution of the Social Contract— for instance, people can work every hour God made, yet not be able to afford to feed their families— & despite the decades of Neoliberal propaganda that insists such a situation is the fault of the individual in question, I think most of us can see that structural inequality has deepened before our very eyes. Furthermore, it FEELS unfair, & human beings, like most apes, strongly dislike unfairness. It’s a species characteristic— we’re social animals. Fair sharing is one of the oldest human laws. This is not to say that life is or should be fair, but that we feel when it’s not. And basically, that’s why it’s easy to imagine how good it would feel to smash the machine you hate.27

Stone Age Dreaming

Last night I watched this interview between Paul Kingsnorth & Mark Boyle. I remember when I found Boyle’s book The Way Home in the library some years back. It was exciting! Boyle wrote in pencil, by candlelight, at his kitchen table, & I felt that was tangible in the text. (Working out that Boyle was born only a few months before me was partly what got me started on Hinge Theory.)

In this interview Kingsnorth & Boyle discuss the idea of the Butlerian Jihad— the idea, from Samuel Butler’s Erewhon, of stopping technology at a certain point in history.28 If so, where would you stop it? Boyle doesn’t have to think too long— the Palaeolithic, he says. (Playing games like this hits different if you’re female, but his answer is the same as mine for the game ‘If you could go anywhere for a day, where would you go?’) Kingsnorth obviously also spends a lot of time thinking about the Palaeolithic, because they immediately get right into it.29

Maybe it’s because Boyle, in profile, resembles my friend Andrew, but I fell asleep after watching this & dreamed about making muka. My first memory of Andrew is sitting on the verandah in the sun learning how to make muka, string made from the fibre inside the long harakeke / flax leaf. You use an obsidian blade & the edge of a mussel shell, & then ply the cord on your thigh. This fibre is what all garments were made of, cloaks & so on, in the old days, a few hundred years ago, & making muka is a consciousness-raising activity— how many weeks & months of labour such a garment represents.30

I woke up from this cord-making dream in the early hours thinking about the interview. I know people who live more or less like Boyle— well, less, because both Boyle & Kingsnorth are extremists by nature. (In my experience, this need for hard rules is an addict thing. Tech = druglike, so this makes sense.)

Boyle, at the end of the chat, proposes the question “What is your last inch?”

That is, where will you not capitulate?

That seems like a Luddite question to me.

Ever Feel Like You’re Being Cheated?

The Large Loaf makes me think about how sometimes you buy a product you’ve bought many times before, but they’ve done a packaging upgrade, then when you buy it, you find that there’s less in the packet. It’s the underhandedness that’s galling. The manufacturer expects you not to notice, or once you’ve handed over your money, not to care, I guess. You buy ‘a loaf of bread’— yet surely the loaf was larger last week? Last week’s bread has been eaten, so there’s no way to compare, but you have a feeling you’re being cheated, little by little.

When it comes to the products of Big Tech, the architecture of the new world, this piecemeal cheating is the playbook, the entire modus operandi. You go to use a front-end you used yesterday, & find they’ve rearranged the whole thing overnight. (This happened to me this morning.) You may not like the new layout, but there’s nothing whatsoever you can do about it.31 Yet, despite what purists might wish, it is not possible to reject these constantly metastasising technologies altogether. Tech these days is more like food than cigarettes— you can’t go cold turkey. Even partial refusal brings serious (social / economic) repercussions.

Anyone who has ever run into a problem with one of the tech behemoths knows the futility of trying to get to a human being inside them. (To be fair, this is not yet the case here on the Stack.) Although these giant beasts of silicon are designed, made, wrought, & maintained by humans, the people pulling the levers are hidden within a labyrinth of obfuscation. I know how addiction works, too, & regardless of whether most people would name themselves addicts, here we are in a world where you can be in a car driving down the expressway at 110 km per hour, & if you glance over at the other drivers, around a third of them are on their phones. (Again, this happened to me the other day.)

Big Tech comes wrapped in metaphorical packaging that is itself the outcome of a kind of human-psyche-mining, its metaphors designed to appeal as universally as possible. This is… a cloud! This is… a place you can hang out with your friends! This is… a house you’re building, on land you own! This is not at all a way for us to harvest & sell your precious data, no, I thought we were buddies! I’m so hurt you would even think that! Besides, technology is neutral! It’s your fault if it makes you feel bad!

Like— gummon bro. I know it’s about profiteering. All that lying just adds insult to injury.32

…Yet here I am, pretending you can talk to Big Tech, when the whole point is that you can’t. This human willingness to pretend is exactly the crack through which they slip into your brain.

Why does everything have to be so fucking… evil? This relentless trapped / tricked feeling, tiny cog against big machine, forced to submit in order to survive, feeling used / extracted / parasited on daily: the emotion this sparks (for me at least) is deep monkey rage. For now, at least, we can still talk to each other this way— through the portal— so let’s keep doing that for as long as we can. And let’s hold to the ancient truths, that place & people matter, that fairness is real, that honour is possible, that work is for love as well as for money & always has been.

Countermagical Specificity

In my recent Ask the Farmer columns, I’ve been thinking about information-sharing, the distribution of knowledge that is PARTICULAR, ARCANE, USEFUL, & TIMELY. Specificity of place (& therefore knowledge) is a good antidote-medicine to the cultural erasure Big Tech is seeking to enact. Pay attention to where you are, & to the knowledge & wisdom humans have gathered through a history of interbeing with that particular world of matter. By which I mean, study culture. As Tyson Yunkaporta advises, don’t go borrowing someone else’s indigeneity; rather try to learn your own.

There was a time when everything was made by hand from available materials— tools, food, clothes, shelter, art— made to last as long as possible. Historically speaking, that Age of Handmaking was not very long ago, & it lasted a very long time. As I have said, humans are deeply affiliated with the ingenuity & labour of doing things by hand; a Way that is really Many Ways, of necessity hyperlocal & thus extremely specific, infinitely diverse. It is not an exaggeration to say that’s what culture IS. What does a tech corporation understand or care about the weather in your garden, where to gather shellfish, or that embroidery stitch your Grandmother taught you? Not only does the corporation not know or care, it wants you to forget that you know & care, too.

What Works / What is Most Beautiful?

The central question when you’re doing things the old way (slow, small, laborious, local) is one of first principles— What works? (Mark Boyle, in the interview with Paul Kingsnorth, says that his go-to question is ‘What is most beautiful?’)

Chellis Glendinning writes in Notes Toward a Neo-Luddite Manifesto (1990): “Neo-Luddites are not anti-technology. Technology is intrinsic to human creativity and culture. What we oppose are the kinds of technologies that are, at root, destructive of human lives and communities.”

The tools we use shape us as we use them. A good honest tool is a thing of beauty; a bad tool these days is worse than unbeautiful, it is a kind of half-alive parasite spy tinkering always with the precious architecture of your brain. It is increasingly imperative to pay attention to how tools feel, & to act accordingly.

Therefore, “We favor the creation of technologies that are of a scale and structure that make them understandable to the people who use them and are affected by them. We favor the creation of technologies built with a high degree of flexibility so that they do not impose a rigid and irreversible imprint on their users, and we favor the creation of technologies that foster independence from technological addiction and promise political freedom, economic justice, and ecological balance.”

Kākā Conversations

When I think about craft as countermagic to the Machine— if I try to think of the most anti-Machine object I own— I think about the gift Ben the Stonecarver gave me, a karanga manu: an instrument for talking to the kākā of my city. (Big green parrots that go round in noisy gangs.) The karanga manu is traditionally used for hunting, but this piece was something of an experiment. We conversed on hole depth over many months & Ben tinkered with making holes in stones, eventually basing the proportions on a wooden karanga manu Amy had given me, made by Thomas Carroll. Ben shaped the pebble from its given form the old-fashioned way, by rubbing stone on stone. He said “If it’s not right, you can give it away & I’ll make you another one.”

This technology is literally Stone Age. It works, of course: when I wear this carving around my neck I know I’m likelier to see the kākā. The type of magic it employs is like attracts like, also a musical magic— an instrument wishes to be played. You could say that the city is a field of possibilities & this tool draws certain tunes & stories from it. On the mountaintop at evening I sat on the top of a bunker playing my instrument to the kākā, who had come to roost in the high pines. As I was there early, I had gone into each bunker to test which one had the best acoustics, & chosen the one on which I was sitting. The evening light was very beautiful & my heart was high. I could see the whole harbour from up there, as well as Te Wai Pounamu (origin of the stone) & the ocean between. Nobody was around but me & the kākā. I tried to imitate their conversation, & they came flying over to see what I was up to, very close: I could see their wing-pits. When my friends arrived & we went into the chosen bunker to sing, there was graffiti on the wall— WIZARD OF WELLINGTON.33

I had been wearing this piece of stone for a year or so when I noticed that the kākā had moved into my neighbourhood; they have taken to roosting in the pine trees on the high ridge. The generative resonance of this one object! Extremely magical, sure, made by Wizard for Wizard, yes. (BUY WIZARD MADE & KEEP YOUR MAGIC WORKING!) As I have said, it is not possible to have clean hands in the modern world, but that makes it more important than ever to channel your ingenuity into magical interventions in the world of matter. It is our task now to seize and redistribute the wealth that is time.

In the Name of Ludd!

I kept coming back to one quote out of all the reading I’d done. It was this, by Kevin Binfield: “Luddism is generated not by conspiracy or the sudden emergence of class consciousness but rather by a single forceful act of naming—the creation and appropriation of the eponym Ned Ludd.”

As I mentioned at the start (many moons ago— if you’re still with me, ka pai!) I’ve been calling myself a Luddite for years now. As I researched Luddism, I realised my historical ignorance. In the writing of this essay, though— in trying to consider Luddism through a Wizardly lens— I came to realise that the most interesting thing about Ludd is the very fact that his name survives.

As I have outlined, what the Luddites did, machine-breaking, was part of an ongoing practice: yet it’s the word Luddite which has come down to us 200 years later, shorn of context but more or less intact in meaning. ‘The Luddites smashed machines in protest’. I have noted that Luddites were Luddites, as distinct from general machine-smashers of the late 1700s & early 1800s, precisely because of what they named themselves— because of Ned Ludd. Ludd, as I have explained, was not a real person as such— he was a folk hero, a sort of small god.

It’s my contention that even now, when a person names themself a Luddite, they’re summoning Ludd. Likewise when one person insults another by calling them a Luddite. Joke or no joke, it doesn’t matter— in fact, jokes are highly memetically sticky. The name of Ludd has been kept alive for 200 years in people’s mouths & memories, an oral history meme. We might think of the idea of Luddism as a tool of thought; in the words of Ben the Stonecarver, Your word is your wand. As the invention & invocation of Ned Ludd strengthened the Luddites, let it strengthen you now in your questioning of tech-propaganda, & in drawing the lines of your personal resistance & refusal.

P.S. I got up early to try to see the solar eclipse, & to hack this unruly hedge of a piece into some semblance of a shape in order to publish it. (I’ve been working on it for weeks.) It’s before dawn, & the eclipsing sun is behind a hill, wrapped in a thick grey cloak of rain, but the birds always know— they’ve gone silent. Lit by the weird half-light of the clouded eclipse, I found this in my virtual mailbox. What better place to end than with news of a Neo-Luddite uprising in America & England…

[Anonymous] says: “These kids have put together an ongoing calendar of events called ‘Real People in Real Time’ and encourage the ‘Ludd-curious’ to join in. The events celebrate all that is uniquely human: authenticity, empathy, play, love, sensuality, dance, joy, art, music, community and respect for the natural world. Also included are events that push back on techno-supremacy, and workshops that show the path back into embodied existence.”

Additional Resources:

Blood in the Machine

The Substack of Brian Merchant, a tech journalist turned tech critic. He wrote the excellent book Blood in the Machine, about the Luddites & modern-day tech-resistance, which I am currently reading.

Kevin Binfield - Writings of the Luddites

A book containing virtually all known Luddite writings (& other Luddite ephemera), available to read online at this link.

Luddite Bicentenary

This is a truly excellent resource, a blog published from 2011 - 2019 to coincide with events that had happened 200 years earlier.

The machine breakers - Eric Hobsbawm

A 1952 article by a Marxist historian concerning the historical context of frame-breaking.

Framework Knitters Museum Video Gallery

Here you can see how framework knitting works, & some Luddite history vids.

Working Class Clothing Late 18th Century

Some paintings of what poor people wore at the end of the 18th Century. Note the last painting: the French Revolutionary sans-culotte in long trousers. (Weirdly, the Early 19th Century Western Fashion Wiki page has no poor people, it’s all just high Neo-Classicism, which in itself is interesting, in that we can see how the French Revolution altered fashion forever.)

Librarian Shipwreck - Luddism

A list of Ludd-themed articles from a very good blog about libraries, technology, activism and impending doom, written by a mysterious librarian known as Z.M.L.

Folk London - Jennifer Reid interview: "I want you to be motivated by your ancestors."

An interview with my friend Jenn, a scholar of Lancashire weaving history. Her Bandcamp is here: Jennifer Reid - The Ballad of the Gatekeeper.

Chellis Glendinning - Notes Toward a Neo-Luddite Manifesto

Neo-Luddite Manifesto of 1990. “Neo-Luddites are 20th century citizens — activists, workers, neighbors, social critics, and scholars — who question the predominant modern worldview, which preaches that unbridled technology represents progress. Neo-Luddites have the courage to gaze at the full catastrophe of our century: The technologies created and disseminated by modern Western societies are out of control and desecrating the fragile fabric of life on Earth.”

From this very good overview of Luddism: The Baffler - A Nod to Ned Ludd

Z.M.L. of Librarian Shipwreck puts it this way: “The ground on which much contemporary discourse around technology takes place is the ground that has been set by technology’s advocates and the technology companies themselves. It’s rather invigorating to read past technological critics who were a bit more willing to come out and simply state that certain technologies are bad… There is a widespread belief in contemporary computer dominated societies, that regular people are not allowed any say in the discussions around the types of technologies that radically reshape their lives. And the way that the term Luddite is commonly used functions to reify this belief by making people believe that they cannot push back against technology.”

Gaughan is at the height of his powers here, & it’s a testament to his genius that even though there’s a minuscule lag between image & sound, the video has been viewed 271,000 times.

Which you can read here: The True Levellers Standard Advanced: Or, The State of Community Opened, and Presented to the Sons of Men. One thing to understand about the Levellers is that they were responding to the betrayal of revolutionary hope— the King’s head had been cut off, Oliver Cromwell had become ‘Lord Protector’, yet the lot of the poor hadn’t really improved. (The bit that begins “O thou Powers of England, though thou hast promised to make this People a Free People, yet thou hast so handled the matter, through thy self-seeking humour, That thou has wrapped us up more in bondage, and oppression lies heavier upon us…” is a response to that particular betrayal. Like WTF— how come we still have landlords & bosses after the revolution?)

Full lyrics here: 27th January 1812: Song 'General Ludd's Triumph', Nottinghamshire

Richard Conniff says: “According to the story, a young apprentice named Ludd or Ludham was working at a stocking frame when a superior admonished him for knitting too loosely. Ordered to ‘square his needles,’ the enraged apprentice instead grabbed a hammer and flattened the entire mechanism.”

Adrian Randall: “Robin had famously robbed the rich to give to the poor and defended the weak against arbitrary baronial power. But Ned Ludd epitomized the right of the poor to earn their own livelihood and to defend the customs of their trade against dishonorable capitalist depredators. While Robin, a displaced gentleman, signified paternal protection, Ned Ludd evidenced the sturdy self-reliance of a community prepared to resist for itself the notion that market forces rather than moral values should shape the fate of labor.”

Peter Schjeldahl: “I like to say that contemporary art consists of all art works, five thousand years old or five minutes old, that physically exist in the present. We look at them with contemporary eyes, the only kinds of eyes that there ever are.”

Lots of people sing this song, which is about extreme poverty to the point of starvation during the Industrial Revolution, but my friend Jenn (an expert on Lancashire weaving songs & history) hates it, so I won’t include it in this essay. More info here: Mainly Norfolk - The Four Loom Weaver

Exhaustive men’s striped-stocking list here: 18th Century Striped Stockings

I found it. “The price per kilo has hardly risen lately. It’s hard to get by.”

It’s here: Frame-Breaking Act 1812. Note that refusing to dob will get you fined or imprisoned; nevertheless, as we have seen, virtually nobody grassed.

This piece of legislation also details the creation of the ‘Specials’. I am no legal scholar but as far as I can make out, it says that any man on the poor list, i.e. receiving parish welfare, is obliged to take a job watching the machines: “every Man residing within any such Parish, Township, or Place, above the Age of Seventeen Years, and charged or assessed to the Rate for the Relief of the Poor therein, shall be subject and liable to the Duties of watching by Night and warding by Day, according to the provisions of the Act…

Every Person so appointed to watch or to ward, shall, during his respective time of watching or warding, to the utmost of his Power, endeavour to prevent all Murders, Burglaries, Robberies, Affrays, and all Felonies, Outrages and Disorders; and for that End, each and every of them is hereby authorised and empowered to arrest and apprehend all Nightwalkers, Malefactors, Rogues, Vagabonds, and other loose, idle, disorderly and suspicious Persons…”

Lord Byron, in his maiden speech to the House of Lords (in late February), came out against the Bill, on the side of the Luddites:

“Nothing but absolute want could have driven a large and once honest and industrious body of the people into the commission of excesses so hazardous to themselves, their families and their community… How will you carry the Bill into effect? Can you commit a whole county to their own prisons? Will you erect a gibbet in every field and hang up men like scarecrows? or will you proceed (as you must to bring this measure into effect) by decimation? place the county under martial law? depopulate and lay waste all around you?… Are these the remedies for a starving and desperate populace? Will the famished wretch who has braved your bayonets, be appalled by your gibbets? When death is a relief, and the only relief it appears that you will afford him; will he be dragooned into tranquillity? Will that which could not be effected by your grenadiers, be accomplished by your executioners?”

Not that the Luddites weren’t happy about it, as evidenced by this anonymous letter sent to Home Office Secretary Richard Ryder shortly afterwards:

“Every frame Breaking act you Make an amendment to only serves to shorten

your Days Theirfore you may Prepaire to go to the Divel to Bee Secraterry

for M r Perceval theire for there are fire Ships Making to saile by land as well

as by Warter that will not faile to Destroy all the Obnoctious in the both

Houses as you have been at a great Deal of pains to Destroy Chiefe part of

the Country it is know your turn to fall The Remedy for you is Shor De-

struction Without Detection--prepaire for thy Departure and Recomend the

same to thy friends

your Hbl sert &c

Luddites”

It can be read here: Kevin Binfield - Writings of the Luddites

Hobsbawm’s very interesting (& very Marxist) 1952 essay is here: The Machine Breakers

Binfield: “The protesting workers whom we call Luddites varied from region to region and even within each region. The Luddites in Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, and Leicestershire were framework knitters, also called stockingers, in both the hose and lace trades. There is very little evidence of persons who were not framework knitters participating in any attacks on the wide stocking frames that were the targets of Midlands Luddite protests and destruction...

In the West Riding of Yorkshire, most Luddites were cloth dressers in the woolen industry, also called croppers; however, Luddite assemblies near Huddersfield regularly included members of other trades—saddlemakers and hatters, for instance... Cheshire and Lancashire Luddites are typically said to have been cotton weavers; however, spinners, colliers, fustian makers, and women working in no textile trade at all were quite likely to be found in the midst of Luddite riots in Manchester and the surrounding cotton towns.”

Russia’s ongoing violations of the Continental System were the cause of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812

It was thought by some at the time that Luddite actions were a French-funded plot to sabotage the war effort, though there is virtually no evidence for this claim. It is very interesting to note, though, that many traditional folk songs express sympathy for Napoleon, including The Bonny Bunch of Roses, Napoleon’s Dream, Grand Conversation on Napoleon, etc. Mike Yates: “No matter what the history books tell us about Napoleon Bonaparte’s envious eyeing of Britain, we know that the labouring classes saw him in a vastly different light; not as a tyrant, but as a possible liberator who would free them from the sufferings which were imposed upon them by the then current social and economic structures.”

There is a good movie about this: The Madness of King George.

(True facts, it was adapted from the Alan Bennett play ‘The Madness of King George III’, but they had to drop ‘III’ off the end because the Americans were like “Is this a sequel?”)

As for the Prince Regent, well… I got my education from the BBC… (Sidenote: I only just realised that Blackadder in Series Three is a Jeeves-variant. Hugh Laurie plays the Prince as pretty much Wooster in a wig— he’s good at idiotic toffs LOL.) In real life, as I said, the Prince Regent was far more rotund.

Last night I found the entirety of Blackadder on the Internet Archive, not sure how long this link will last as the Beeb are like hounds for piracy, but here tis anyway: Blackadder Remastered: The Ultimate Collection

The Luddite Bicentenary blog describes how these factors played out in Nottinghamshire. “The early 1800s saw a declining market for hosiery and lace, chiefly influenced by the closing of foreign markets with the introduction of the Orders in Council [i.e. Napoleon’s trade blockade] in 1807. Unemployment was severe: William Felkin records 4248 families receiving relief from the poor rates in Nottingham in early 1812 – a total of 15,350 people – half the population. Also in 1807, the expiry of a 20 year-old agreement between stockingers and hosiers regarding prices paid for work led to a veritable 'race to bottom' amongst hosiers.”

My jeans include a preachy label exhorting me to care for our planet: wash less, wash cold, line dry, donate or recycle. I read this as a greenwashing attempt to obfuscate the environmental damage the jeans represent.

I thought here about George Orwell’s essay Down the Mine: “If coal could not be produced without pregnant women dragging it to and fro, I fancy we should let them do it rather than deprive ourselves of coal. But-most of the time, of course, we should prefer to forget that they were doing it. It is so with all types of manual work; it keeps us alive, and we are oblivious of its existence.”

Tyson Yunkaporta has a thing about the inadequacy of the Reo Ingarihi word ‘we’. He deploys more specific grouping-words translated from the indigenous, such as ‘us-two’ or ‘us-all’: “There’s also the ‘us-exclusive’ which is just us, not them. You have exclusive groups. But then you also have to have those groups working with other groups, so there’s also an ‘us-all’ pairing.”

A brief summary here: Max Rashbrooke: What the left and right still get wrong about 1980s politics

On this subject, I recommend the excellent history Women's Work - The First 20,000 Years: Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times, by Elizabeth Wayland Barber

It’s also why Luigi Mangione became, rightly or wrongly, a modern-day folk hero.

Alexander Beiner wrote an excellent essay explaining the Mangione phenomenon as a ‘breach event’, an instance of re-embodiment: “So what does metaphysics have to do with the assassination of Brian Thompson?… What’s particularly powerful about this breach is that it re-embodies accountability… Big pharma treats living, breathing people with qualitative experiences as meaningless quantities. What the killing does, and what gives it so much power as a breach event, is to remind us that the body is the source of ultimate reality. It is the container of all qualitative value. It forces us to acknowledge that quality is more real than quantity.”

Beiner also points out in this essay that “Machines are also embodied; they are physical and present in the world in a particular time and place. This can be hard to remember, because elites want it to be hard to remember… But they are still embodied, even if they appear not to be. They run on silicon and coltan and copper, housed in servers that can be destroyed, hacked, or damaged.”

Read the rest here:

More on the Butlerian Jihad here, from Edward Ongweso Jr:

I discussed that here: Obsidian Smartphone

I also wrote about how my friend Anne thinks electricity is the problem, here: Darknesses / Nightself

Te Ara - Story: Māori weaving and tukutuku – te raranga me te whatu

The dream was possibly also due to my construction of this cord to anchor the kitchen sink plug to the tap:

Furthermore, anger feeds the Machine. In the immortal words of Al Swearengen…

I note that since taking a massive whack of venture capital, the local overlords have stopped talking about building a house on land you own. (Nevertheless my brother, I still believe your heart is true, I know you’re trying to do a good thing, thank you for the whisky)

If you want to vote for that little hooligan the kākā in Bird of the Year, you can do so here: Bird of the Year. Voting closes on the 28th of September.

Can you please design a T-shirt with 'summoning Ned Ludd' on it?

…dense and interesting…thanks…