“The ancestors of the higher animals must be regarded as one-celled beings, similar to the Amoebae which at the present day occur in our rivers, pools, and lakes. The incontrovertible fact that each human individual develops from an egg, which, in common with those of all animals, is a simple cell, most clearly proves that the most remote ancestors of man were primordial animals of this sort, of a form equivalent to a simple cell.”1

The smell of Kerosene Creek is ambergris, whisky, the armpit sweat of someone hot: a complex, earthy, bodily terroir, rich & hearty as broth. Some tourists leave online reviews whinging that it’s gross & stinky, but they’re fools, unable to appreciate adult flavours. I write in my journal afterwards that the colour of the sunlit water is mouse & tea. The creek floor is white sand. Probably no fish or eels live here, & that makes it feel strangely empty, as if it were made for humans. Noel says the small bits of floating pumice are catching in his leg hair. Jennifer says that the pool we’re in reminds her of the shallow warm pool at a fancy gym where she sometimes goes to lift weights, that she calls the Terrapin Pool. Though it’s bathlike in temperature, the creek-water is not still but ever-moving, gently insistent, pushing with warm cats-paws, an affectionate animal.

The creekness of it, the way a river is a path only partially known (where does it come from? where does it go to?)— the exploratory possibility of that bounded infinitude, constantly refreshed— gives a happy feeling that I know well from my stream-dwelling childhood.

I show Jenn the black mud laid down underwater inside the arm’s-curve of the bank— come over here, touch this. She says it feels like cashmere.2 When you sink your hand into the extremely soft mud, large bubbles are set free, & if you pull a handful out of the water, the mud is luscious black, smooth, sulphurous, anaerobic, glittering with mica. It runs down your arm, liquid darkness. It feels naughty to touch it— undoing the creek’s patient labour— but very nice. Some say a creator made humans out of clay; but mud is where life actually started out, the so-called primordial ooze, the warm soup. Our communal ancestral home is Yin as fuck, lovely-disgusting, female.

Me: “Probably good to put on your face, if not for the amoebas.”3

Jennifer: “We could put it in little jars & sell it to rich ladies on Ponsonby Road!”

She knows Ponsonby Road because it’s where she got her nails done, the nails that everyone comments upon. (That & the piercings in her face, placed according to Georgian beauty marks.) How do you do anything? The folkies want to know. How do you wipe your bum, for instance? Err… the same way everyone does? When Jenn is on stage her nails act like a Thai dancer’s metal fingertips, making her gestures bigger, extending her hands into space, echinoderm spines.

Also— & this is important to note— Jennifer knows what Ponsonby Road means (even though she only got to this country three weeks ago) because she is never not paying attention: looking, listening, noticing, recording, remembering. In short, because she’s a Wizard. We sang together in Wellington— I supported her— then we went to Hamsterfest together, then to Chris’s, then to Tradfest, & now we’re friends, in that hot-housing way of Folk Festivals— islands of time, temporary autonomous zones wherein you hang out all day & sing all night. When I close my eyes at night I can see her face, the same way you see the fruit you’ve been picking all day. The energetic web spins itself, electrical filaments of connection, golden gossamer, as Jenn writes later. Here in the creek we’re missing the third point of our unholy Wizard triangle, Sammy,4 who had to go home after Hamsterfest. From triplets to twins. Witch time.

Later I find out Kerosene Creek’s true name: Hakereteke, which as far as I can make out means ‘mean / stingy vagina’. (I consult my Mum, who gives the same translation unprompted.) I would guess there’s mythology associated with the name, but I can’t track it down. (Secret business, women’s business?) Inside the pair of names is a sound-chime, kere / kero, which makes me wonder if the reo Ingarihi5 name is a bastardisation of the reo Māori.

The amoebae of Kerosene Creek were once our cousins, but these days they’re keen to colonise the planets we’ve become: to get under the blankets of our meninges. I find their name out later— Naegleria fowleri, a free-living thermophilic amoeboflagellate excavate. You can sit in the soup of them, but don’t invite them inside your face. They get in through your nose, then up the stairway of the olfactory nerve to the brain. Then they eat your neurons & stuff. This is very rare, but hard to medicate & often fatal, so better not to put your head underwater.

Sitting in the creek, I’m thinking about thermophilia in general. Tardigrades, & also those colonies of animals— crabs, anemones, & such— that live in the abyssal deep clinging to black smokers, underwater volcanic vents. The Goldilocks zone of being able to adjust temperature by getting closer to or further from the fire, like in Jenn’s song about putting boots right up against fender & smoakin baccy. The cracks where the Earth’s molten interior open to the surface. (Vaginal…) Stable patterns, until they’re not: the Pink & White terraces, once the Eight Wonder of the World, lie buried under volcanic ash nearby. A temporary, volatile stability, then— but the delights of thermalness are so very delightful. Free heat! Due to living in cold houses all my adult life,6 I lean thermophilic myself, ever-hungry to be warm to the bones.

I tell Jennifer about all the hand-related kupu whakarite / metaphors in te reo Māori. Ringawera (hot hands), meaning a kitchen-worker. The one my Mum likes to quote, Moea te tangata ringa raupā: advice to marry someone with calloused hands, i.e. a hard worker. (Jennifer says that these days she won’t date anyone with soft hands— she likes useful men only. I remember the handsome young Czech boy who danced with me at a party once, my cream silk robe swirling out behind me… He led like a man, but his hands were lily-white.) Jenn is inventing ploughboy puns to take back to Kev, who doesn’t like getting in the water (man of Earth). Ploughboy Mansion! Rhinestone Ploughboy! I tell her about the term ihu oneone (dirt nose), meaning a gardener.

I tell her about how if you want to say where you’re from in te Ao Māori, you name your mountain, your river, & so on, & so on. Ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au: I am the river, the river is me. (The fish Jenn & I saw the first day, in the limpid cold-water stream near camp, a galaxiid or small trout, darting swiftly up the pool under the willow, dark against pale sand, liquid life.)

Green ferns on the bank, rising steam. A big Jurassic dragonfly appears, sun glancing in its cellophane wings. (Imagine this place before humans, imagine the heavy-footed moa, the cacophony of birdsong, the solid walls of green overhanging into the humidity...) A pīwakawaka— then two— flitting among the sunlit leaves, then low over the creek, flirting close to us, almost touching. “Its tail looks like a fan,” says Jenn, & I say that’s its Pākeha name, fantail. Then a black & white bird materialises. It isn’t there, then it is, on a bare branch over the river. It’s a tomtit— a bird I’ve only ever seen once or twice— round like a tītīpounamu, or like the robin I saw in a holly bush in London Winter, a ball with twig-legs. It flies into the tree overhead & yells sweet! sweet!, a big noise from a wee thing.

I ask Vicki, reclining near the bank, if she could sing the song we sang together last year,7 the Manx lullaby Ushag Veg Ruy, which concerns small birds. She sings it softly & I join in, lying on my belly in the water, the words I learnt coming back to me as the song unfolds in Vicki’s mouth, transmitted downriver with the ripples. Did I not sleep on the cold wave’s crest? The sweeter & quieter songs— this lullaby, Deb & Jenni’s waiata— seem to suit the pool best. Creek choir. (Jennifer & I have street voices, pub voices, rather than creek voices.) I often think of folk music as a river. It’s a stream of music that moves through time & through our singing bodies, from the past into the future. The way the songs are shaped & smoothed by much handling, like rocks in water.

Seeing my friends in their togs is endearing. Our clothed selves— our outward-facing presentable selves— are stripped away, shed like skins. Wet & near-naked, humans become more animalish, more babyish, & that makes me fond. Sitting in Kerosene Creek, simmering gently in the cauldron. Eye of newt etc.8 Fragrant steam rising from the pot. It’s the kind of place you stash away to return to later in memory, a calming meditation-token. The river is Motherly in its benevolence, its generosity. You know in your bones this place was a place since people first set foot here, that the paths have been worn in over centuries— desire paths, made by walking. The way the proud tree-roots are polished smooth by bare feet & sand, like the way the stones of London are dished by centuries of shoe-leather.

There’s a man upstream, under the silvery lattice of fallen kānuka, leaning against a rock with a can of Jack & Coke in his hand. Local knowledge. I lizard-crawl upriver to yarn to him. Sure enough, at the base of the rock he’s leaning on, there’s a hot spot. I dig my fingers into the sand at the base of the rock to feel the rising heat. He reckons the further upstream, the hotter; that there used to be a path running twenty minutes walk upstream, but it’s grown over now. He says he cleared the path from the carpark with his chainsaw, chopped back the blackberry, cleaned up some rubbish. It’s mostly locals, he says, who leave dirty nappies & beer bottles lying around. I say that this is so obviously a sacred place, that’s got to be bad luck, polluting it. He tells me that he comes here every Friday to get away from the stresses of life, his many children, his work as a home mechanic. (His partner is too heavily pregnant to come to the creek right now.) We talk about how the old ways are better than the new ways. Old songs, old kaupapa. He says “It’s all become urbanised, modernised, these days.”

I say that we’re on the same page regarding the old ways— we’re all at a Folk Festival in the forest, singing old songs— my friend over there, the one with the blonde hair, she’s from Lancashire, she sings traditional ballads in the dialect of her people. I ask her if she will sing a bit & she swims up & sings a few lines of the Wayver o Wellbrook for our new friend. I say that having heard these songs three or four times now I can follow the dialect, brid for bird, yead for head, whoam for home. (A beautiful one, because it makes home sound like a womb.) Trad Boys, Trad to the Bone.

All the elements mix in this place. Earth in Water, Water in Earth. Fire rising through Water, Water into Air as steam. When you get out of the water your skin feels slippery, mineral-silky, like an eel’s skin. You retrieve the clothes you left draped over a tree branch & reluctantly put them back on. Your fingers are soft prunes. Returning to air you still feel half-melted, heavy; like your bones are warm wax. This body-feeling is similar to the drugged calm one feels after cold-water swimming, a total deep relaxation that lasts for hours afterwards. How is it that water can penetrate flesh this way? How can it do that to your insides? Medicinal alchemy, sure, which could also be classified as magic. Later I show Jennifer the photos I took of her reclining in the creek, sun dappling the water into greens & browns, & she likes that her back looks strong.

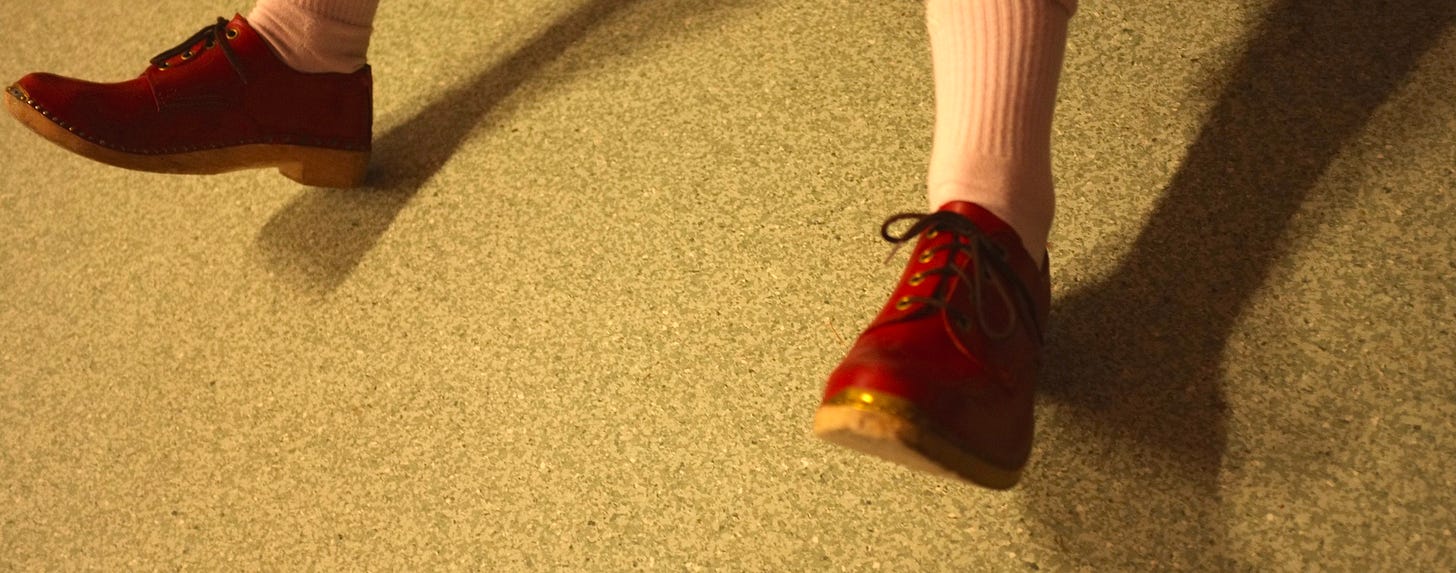

Jennifer Reid is a ballad singer from Lancashire. She sings broadside ballads & Industrial Revolution work songs, & clog dances. None of this describes her true awesomeness, though: she’s a one-woman force of history & politics & comedy, lungs & spark. Jenn loves New Zealand & we love her! With luck she will be back in early 2026, so if you missed her this time, hopefully you can see her next time!

Her website is here: Jennifer Reid

Ernst Haeckel

For some reason I decided to pat the fine-ground coffee into the stovetop espresso’s cup with the pads of my fingers this morning, & it reminded me of the mud-feel. Other things that feel that way: a rabbit’s fur; a baby’s hair; when you touch a wandering anemone, or any other sea creature with flesh so tender you can’t tell where it begins. The word I associate with this ultra-soft quality is loft— in the sense of air (or water) held inside a delicate structure.

I quoted Ursula K. Le Guin’s analogy of intersubjectivity as ‘amoebas having sex’ in this essay.

English

Sammy has a song about cold houses— Wooden Tent, which young Helena Brown sang in the kid’s concert at Hamsterfest. Sammy said to Helena, “That song’s yours now.”

I wrote about last Tradfest here:

Folk Songs & Folk Singers

Simone Weil: “[W]e possess no other life, no other living sap, than the treasures stored up from the past and digested, assimilated and created afresh by us.”

I had a newt dream at Hamsterfest. I dreamed that newts had been released into the waterways of Aotearoa, the males smooth, the females frilly. Jennifer had a song-snatch featuring newts & centipedes, which was what planted the dream-seed, but when I awoke I thought of my correspondence with Paul Sartin, after we met at Auckland Folk Festival in January of 2020. He told me about the pond he was making in his Hampshire garden, & sent me photos. When a newt took up residence in his pond, it was a red-letter day.

Did not know about the fighting clogs!

I am an emissary for the single-celled ancestors in some ways, I believe. I could give a shit about what my Puritan ancestors want, but I am on an eternal peace-and-story-finding mission with all my pre-modern fore-beings. Mothers of my mothers, mothers of my fathers, scaled or feather or slime-people! A good read fot this morning, many thanks!