“This father had made his way to school on his child's skateboard. While the man adjusted one of its wheels, Arthur explained to him that nocturnes were short piano works inspired by moods and feelings at night. The father interrupted him to loudly ask if he happened to have a spanner in his pocket.”1

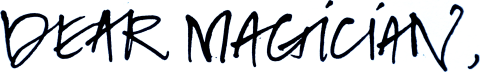

According to Oberon, the two studio keys he’d given me were colour-coded. Keys are tiny tools, but a key is also a space-talisman; proof of the right to enter as well as means of entry. Still, entering the building felt illicit, I think because it was the first time. Will these keys work? Is it a trick? Do I really have access to this hallowed space? Through the metal grille into the small alcove, a drift of Autumn leaves on the tiles. I unlocked & entered the first door. Shutting it behind me muffled the bustling street, & I found myself in a quiet antechamber at the foot of the stairs, stacked signs leaning against the wall, more leaf-drifts in the corners. I felt the minute I entered it that the building was empty or almost empty. Possibly the painter was in his den, but the handful of writers who’d been in the studio yesterday morning weren’t there. I could see slivers of light through the stair-cracks, & hear muffled beats: proof of a room just behind or under the stairs, another building folded inside this one. I started to climb. The paint was eroded in the middle of the stairs by decades of footfall & the lino had worn right through in places, like the ivory veneer of a cheap piano key. Up these spiralling flights to the second door. After quarter of a minute trying the key in the wrong lock I let myself into the studio. Indeed, empty; but there was a small light on, enough to find the main light-switch by, tucked away around the corner.

Generally I dislike carrying too many keys. More stuff, more things; more clutter, more responsibility. My keyring is more of an assemblage of amulets, mostly silver trinkets I’ve found on the ground & Folk Festival entry tokens. There have been glorious times in my life when I carried a single key, or none.2 Although I dislike amassing them, I get sentimental about house keys the same way I get sentimental about worn-out boots. The faithful service these old friends have done— the thousands of days-worth of mutual touch— makes it hard to let them go.3 When I ran a flat, I must have cut dozens of keys for new flatmates, yet few of these keys ever returned. Likely most ex-flatmates are less animist than me; maybe they just forgot. Still, it says something interesting both about human nature & about the trust system of flatting. It’s an odd feeling knowing that there are 25 or 30 people wandering around out there who could theoretically open the front door, but most ex-flatmates aren’t villainous enough to rob. (Really there was only one, & she did it whilst living there, or maybe on the way out, rather than coming back afterwards. Maybe there’s a psychic barrier against reentry once tenancy ends; or maybe it’s just that there’s usually someone home.)4

I illuminated the room, chose a desk, & started writing a letter. Sweet solitude! Now that I was alone in the room I noticed a ticking clock: my most-hated sound. Also, I could hear the street down below, a gentle river of chatter. The people were in evening mode, happily rushing places. I felt suspended in space, like a falcon in its cliffside eyrie. Glancing up from the paper I saw— across the street’s modest canyon— another lit window, level with mine: twin windows, each arched at the top, framing a shadowy room. The dim light made me think it was a home-space, but I couldn’t see anyone moving in there. If I keep working here, I thought, I will get to know this view intimately, these particular angles & alignments— but this first time the vantage point had a shiny feeling, the freshness of discovery. Beyond the facing building, which was pleasingly decrepit,5 I could see a tumble of darkening towers adorned with lit windows that glowed yellow, orange, white in the gloom. People were home, bees in their hives. As the night deepened the buildings faded & the lit windows brightened, seeming to hover in midair under the black wing of the tree-edged ridgeline, until that silhouette too melted into the sky.

I’d run into Anne in the street earlier and they’d told me they had a theory about where humanity went wrong: electricity.6 I said that I agreed. That’s when the ancient rhythms were disrupted, when the dark was blazed into oblivion. (Goodbye, night's rest & refuge…) Light is measured in lumens, the power of a single candle flame. I used to visit a friend who lived in a candlelit housetruck, & oh, the sweetness of those small friendly flames! Like a tiny wing of afternoon’s honey, captured & made to dance. That & the orange firelight glowing through the cracks in the old potbelly stove, like magma in black lava… It made me understand why old paintings look the way they look: that’s how the old world was lit.7 The night was vast; darkness was dark; corners were shadowy; fire and candlelight were warm and dim. Storytime, songtime: mystery & memory play in the dark.

Kev says electricity on tap is consumption disconnected from generation, product severed from source.

“Like supermarket meat,” I say.

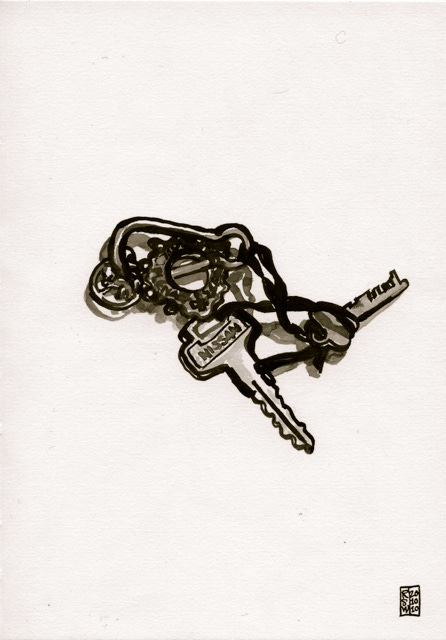

A lit window at night is beautiful the same way a cupboard full of food is beautiful. It satisfies the ancient part of us, I think: it signifies home / warm / safe. From space, lights stand for human habitation; on the night-half of Earth their clusters delineate cities. Sometimes as I move through the city I parse it as an arrangement of dwellings, rooms stacked upon rooms, each one centrally meaningful to someone(s). But there is also something forlorn about looking at lit windows— about being on the outside looking in. At the other end of what a lighted window can mean, I think of the Rider-Waite-Smith Five of Pentacles. Two ragged barefoot figures, one on crutches, trudge through the snow past a lighted church window. They cannot stop, nor can they enter the church. The world is not my home, I’m just a-passing through.8

Walking through the bureaucratic quarter later with my mind still on light, I looked up at the cliff-faces of Wellington’s towers & saw how the lighted rooms of the office blocks were a cold, harsh white: the worst light of all, bright fluorescent. Probably cleaners were at work in there, the night-time denizens, invisibly labouring. (The daytime office workers have little consciousness of these night workers, as if elves washed their cups & emptied their rubbish bins while they slept.) I remember how it felt to work inside those impermeable places: the spaceship-like sterility of air & light & surfaces. Only the hardiest plants could survive such conditions— so how could it be healthy for human beings? It used to boggle my mind that people spent whole decades of their lives in offices, seemingly happily enough. (People can get used to anything. I remember the Winter, though, when the young Southern Right Whale Matariki took up residence in the harbour, the way productivity slowed to a trickle as the office workers pressed their faces to the windows of their towers to watch him frolicking.)

Later, riding the bus home. The barely waning moon was hanging high in the clear sky, & as the bus followed the spine of the land I had a birds-eye view to East, South, & West, looking down on the landscape below. (It felt something like standing over a model train table. Wellington, because of its hilliness, is good for these dramatic long vistas.) To the East I could see the harbour mouth, bright ocean-stripes laid between the black hills. The moon was spilling its light onto the water in great swathes of glowing silver; not a single white track like it makes when you’re low to the water, but spreading soft-edged stains of light, like fallen cloud. A cold light— but magical, antithetical to the feel of those glaring downtown fluorescents. I think it has to do with gentleness. Moonlight is bright enough to see by, to cast a shadow, but it drains away colour. The colour is still there— it can be seen by a camera:

…but not by our eyes, & that’s restful. A whole swathe of information (colour) has been removed. Darkness is a rest from having to look.

There are darker darknesses and gentler lights still. Consider starlight: it takes a long time for the eyes to adjust to such subtlety, such ancientness of illumination. Pupils dilate slowly, petals opening, portals. This expansion is not effortful, it’s more of a letting-go, like a fist relaxing into an open hand. The feeling is of an ancient animal-self stirring & waking. The Magellanic Clouds appear, the Jewel Box, the black nebula Pātiki9… After half an hour or so one has one’s true night-vision, but it’s a delicate creature. Any glimpsed light contracts the pupils & takes you back to square one. It’s interesting to me that seeing & hearing into the dark takes time, as if night is elastic, stretchable. Silence & darkness seem like presences to me rather than absences: only inside their gentle spaciousness can the nocturnal self emerge.

Aotearoa is benevolent, lacking any deadly animals, so one can walk in the night trustingly. It’s possible, also, to be totally alone. A still warm Summer night in the middle of nowhere can feel Edenic. In the deep darkness of a moonless night glow-worms can be seen, their small greenish lure-lights starring the velvet of wet banks, the ceilings of caves. Or in the sea, phosphorescence: you move your hand through the dark water & it spangles into temporary galaxies. These are subtle phenomena— even a bit of moon will drown out their tiny illuminations.

We’re all forced to see & hear so much these days, an assault of light & sound. Silence & darkness are privileges; the subtleties of visibility & audibility are themselves obscure, swamped by the electrical mundane. Nightself must be exceedingly rare in the modern world, an endangered state not only through personal choice but for lack of true dark places. It’s possible that many (—most?) people have never experienced the awakening of nightself. Many (—most?) people blind themselves constantly with the flickering light of screens. I feel some guilt about writing to you here inside the glowing box, adding my energy to its glare, luring you further into the world of bright light. The visibility of being online makes me crave shade, silence, obscurity. I wrote recently: “Against isness, isn’tness: Yin, shadow, emptiness. Stepping into a cool dark room, after walking a long way in the blazing sun. Welcome, friend— sit here— drink this water! (The water is drawn from a well. It tastes like stone.)”

Dark-deprivation & silence-deprivation are ubiquitous states in the city, in modernity. I grew up in the bush & I crave darkness like a drug. My friend Sammy is currently compelled by circumstance to dwell in the city fringe, hard up against the motorway. He tells me how he’s being driven mad by the relentless noise: hedge-trimmers, lawnmowers, powertools, boyracers, motorbikes, sirens, helicopters... (I know his street well, because I used to live on it myself: I would pretend the cars on the motorway were waves on a shingle beach.) Sammy’s a musician— he’s ears as I’m eyes— & it’s the spacious silence of the forest night he craves. Both noise & light can be used as instruments of torture, so there must be something to the idea of a universal need for peace & quiet. Under tenancy law, one has the right to ‘quiet enjoyment’, which I think is a nice phrase.

I was at a party once where I knew almost nobody. I found myself standing next to the hostess, who was somewhat crestfallen. “All I wanted for this party was for people to dance, & they’re not dancing,” she said to me.

I considered the dancefloor: it was cute. The music: it was good. Then I saw the problem. “Turn that light off.” I said. “It’s too bright.”

She turned the light off, & within a few minutes people began to dance.

I woke up remembering the darkest dark & quietest quiet place I’ve been. It was inside the earth; a return to the cave. I was around 20, & my friend Joe had discovered a secret door into the network of tunnels under Albert Park, built as air raid shelters during World War II.10 (A few notes about Joe… My earliest memory of him is his magnificent crown of hair on the school bus. He grew up by the lake, quite near to the swamp, & I remember sitting next to him at a teenage party one time, his legs & arms black with mosquitoes. I was agitated by this but he was totally chill about it: Just let them drink & leave, it’s easier that way. Swamp Zen, I guess. Another cave-related Joe fact is that he had his 21st birthday party in the massive cave at the end of the beach, with candles stuck on the projecting rocks of the walls & a generator for music.) Anyway, we— me, Meg, Tom, Joe?— crawled in through this small door in the hillside. The tunnels had been half-filled in with rubble, so we had to clamber our way in over the top of this rough terrain, sometimes closer, sometimes further from the concrete ceiling.

Our home beach caves have a certain form— spread volcanic cracks— lofty Cathedralesque mouths dwindling to tapered ends, walls studded with boulders, black sand floors silken underfoot. There are whole networks of them. (We knew them well… When to go in to avoid being trapped by tides… The technique of moving through the darkness with your hands up in front of your head, so as not to get sconed by a projecting boulder… The meandering lines of glow-worms along the top seams…) But these tunnels felt different. Man-made, square-edged, repetitive, dirty, claustrophobic. To penetrate deeper into them was a kind of dare. They were laid out in a grid formation, which made them frighteningly samey: no waymarks, so if you wanted to deviate from a straight line you had to take a ball of string in, like Theseus. The shadowy tunnels stretching beyond reach of torchbeam to left & right— obviously there were no cave-bears in there, but tell that to the hominid brain! Once we had passed a number of side-tunnels, we paused, deep under the earth now. OK, said Joe: now switch off your torches.

Absolute dark, absolute quiet: the darkness so dark that the eyes start to embroider patterns onto it, the silence like a weight, like a heft, a present absence. The deep blanket of earth overhead blocks out sight & sound of surface life. What lives, down here, so far from light & warmth, so deep underground? Fungus, maybe, lichen, some kind of cave-dwelling insect? Inside the land’s body it’s nothing like the warm gloom of the human womb (the snug embrace, the ceaseless rocking, the neighbouring thump & gurgle of heart & guts & lungs, the outside muffled through a wall of muscle); rather, the chill damp, the dumb of the grave.

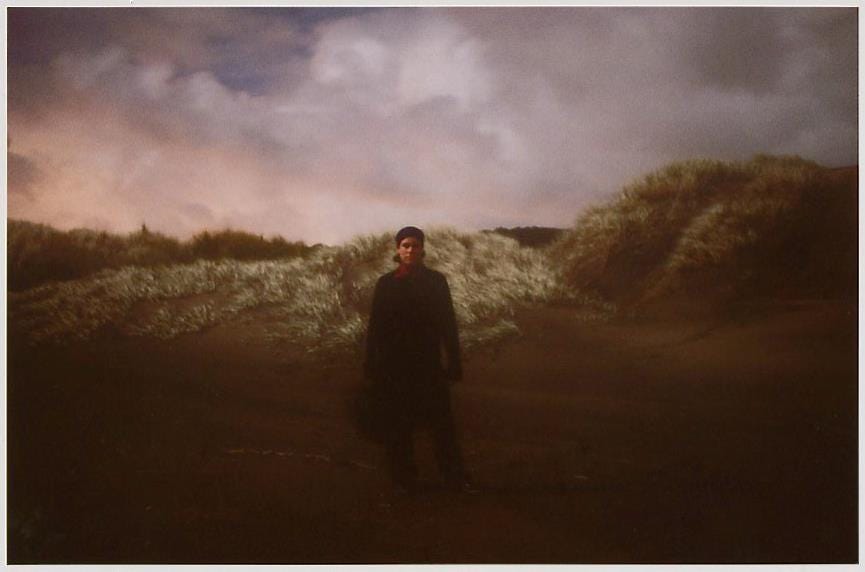

I couldn’t work out how to finish this piece. Then, last night, faced with the prospect of sitting in the cold for half an hour waiting for the bus, I decided to walk home. It’s a feature of Wellington’s aforementioned precipitous geography that sometimes you have to go circuitous routes to get where you’re going. As the crow flies, my house was just over the ridgeline, & it annoyed me to have to go the long way round then double back. I decided to take the bush track over the hill. Theoretically I knew the tracks linked up at the top: I’d walked them in the past, but not for many years. Still, how hard could it be? Up & over. I turned away from the streetlights into the dark forest & switched on my phone torch, checking the battery to make sure it wasn’t going to die while I was in the middle of nowhere. The path was not much more than a sketched suggestion in parts, a line cut into the hillside.

It was less muddy than I’d expected but the leaves were slippery underfoot & for once I didn’t have my proper boots on: I was wearing the boots I bought in London.11 I wore these boots for the first time in Barcelona. Possessed, driven by the need to see, I walked for hours in the day, then again in the night.

Walking so far in new boots gave me savage blisters, & later the little toenail on my right foot— my slightly larger foot— went black & almost fell off. I’d been scared of the boots since, as if they were an animal that bit me. I’d decided that morning to wear them again, resolving not to walk too far in them— yet here I was, walking far. (Maybe wanderlust is embedded in this particular pair of boots. Residue of the last owner, who wore them from Aotearoa to Rānana?)12 Anyway, I placed my feet mindfully, so as not to slip & fall in the mud, or— worse— off the path. Nobody knew I was here.

Quickly leaving the suburban lights behind, I climbed into the dark embrace of the land. The path zigged & zagged— a longer walk but a gentler climb. At least it had stopped raining. I was carrying a number of bags, containing laptop, library books, groceries, plus all my everyday kit, but I didn’t have an umbrella or a raincoat. I’d thought the trees would provide some cover if it did rain, but as I approached the ridge the path opened out to the sky. The wind was whistling on the tops, but it was good to be up there alone, away from other humans.

When I reached to the crest of the hill other paths appeared. I chose one that seemed to be pointing in the right direction, but before too long it led me back towards the city lights. Wrong way!

The paths had wiggled so much I’d got turned. I backtracked to the trail map I’d passed earlier & studied it some more. It seemed I had to go back to go forward: a left, then a right. This was all taking longer than expected, but I’d got myself here (Where? Here!) & I had no choice but to walk on, to get myself out again. I remembered I had snacks in my supermarket bag. I dug out an apple & ate it as I walked. My mouth understood the apple differently in the dark. When a light appeared behind me I thought I was imagining things, but it was a runner with a headlamp on, the first other person I’d seen. I stepped aside to let him past. His bare brown calves were ahead of me, flexing in my light, then he disappeared round a corner. I had briefly considered asking him which way to go, but pride stopped me. In any case, I guessed that his presence meant civilisation was nearby.

The new track I was on was a wide road sloping down. There was water running over it in a thin layer, as if it were a streambed, & it soon led me into total darkness. I was now in a fold of the hills, tucked away in the tops, no human lights visible, only a few stars. Misty cloud was hanging on the dark ridges across the valley & I heard frogs singing close by. Frogs! Of course, I thought— I was trying to talk about dark, but that was all theoretical— I needed to walk into the dark to remember the dark. I trudged onward, thinking about blisters. Suddenly, houselights ahead. The paths had carried me back out of the dark. I emerged at the top corner of my own suburb. As I walked down the hill, a bus came past, then another, nearly empty, big yellow deep-sea fish.

“I labour by singing light

Not for ambition or bread

Or the strut and trade of charms

On the ivory stages

But for the common wages

Of their most secret heart.”13

Deborah Levy, August Blue

I feel this way about stuff in general. Initial reluctance to acquire more things— yet once things pass into daily usage I become deeply attached to them, as if to a living thing, a pet, maybe. I have noticed that some people love to acquire stuff & don’t seem to experience ambivalence about it. I think my horror of stuff has to do with a personal aversion to responsibility, but I also think it’s related to housing. Secure habitation and abundant living space are the preconditions of stuff-acquisition.

This dance of stuff-acquisition vs getting-rid-of-stuff is an interesting subject that I might write more about in future. Stuff also seems to touch on Wizardwear, which I wrote about here & here: the idea that a Wizard carries their kit with them.

The lichenous grimy textures of these old buildings make me nostalgic for the old Wellington, how it looked when I first visited 30 years ago

Afterwards I recommended them this essay by Lucy Ellmann: Sing the body unelectric

Ellmann: “I’ve come to see electricity as a kind of ethereal rapist, that can’t stop interfering with everyone…”

Goya painting into the night by the light of the candles stuck all round the brim of his hat

From Tom Waits’s secular gospel, Come On Up To The House

=Flounder. (Ingoa Ingarihi: Coal Sack.) This black nebula can be found nestled into the flank of the Southern Cross

In central Auckland

I ordered the pair on the left from McKinlays in Dunedin. While I waited for them to arrive, I found the pair on the right in an op shop in Newtown, for $10: also made by McKinlays, though under an alternate name, A Good Thing. I hadn’t been in London more than a few days when I found the pair in the middle, in a charity shop in Dalston. They were the bastard child of the two pairs I’d brought, ankle boot cut but made of nubuck. Sure enough, they were A Good Thing. (For reference, this is an obscure NZ brand.) But surely they wouldn’t be my size? Yes: they were exactly my size. I bought them. Anyway, it was these boots that tried to eat my little toenail in Barcelona, & these same not very rugged boots (delicate material, non-grippy crepe sole) that I was wearing last night on the slippery bush track.

London

From one of the first poems I ever memorised. Dylan Thomas, In my Craft or Sullen Art

After I published this I visited my friend Brian. He talked about how dark it is when you're staying in bothies up in the Highlands of Scotland, & he reminded me how sometimes city people totally freak out about awe-inspiring darkness and quietness & demand to be taken back to civilisation. That made me remember the time my friend's posh English girlfriend lost her mind at a New Years party in the far North: a bush doof adjacent to some 60 acres of native forest. She had never been out of the city, I guess, & the majestical Aotearovian wilderness freaked her out so much she ran away into the night. (There may have been drugs involved, who knows...) We were all quite worried, because she seemed not to understand that we were in the middle of a lot of bush & it was a bloody long way to anywhere: a person could get lost pretty easily. Anyway, the next morning she was found in a ditch not too far away, physically unharmed but mentally unhinged.

That old photo under the moonlight! Agree totally on the dark, obviously. Wellington seems a very dark city to me, as they go. But I've never climbed one of its hills in the dark. I ought to.

This electricity thing--it's so compelling to say fuck all this, it cuts us off from the REAL, which it does, mostly, except this is real right now as I type on this screen? As you say above. The dilemma, always. Maybe we just need some dark caves to go play in from time to time. Is that enough? Gonna have to be.