George Eliot, Adam Bede: "With a single drop of ink for a mirror, the Egyptian sorcerer undertakes to reveal to any chance comer far-reaching visions of the past. This is what I undertake to do for you, reader."

For ten years, between 2010 and 2020, I did an ink drawing every day.1 I drew from life or from photos,2 in hardback sketchbooks, A4 and A5-sized. I didn’t pencil, but drew directly with ink, using dip-pen and / or brush.3 My rule was that the drawing had to be started— ink on the page— between midnight and midnight. (I missed this deadline only once.)

I chose ink because of its graphicness4 and its cleanness; I dislike messy media such as charcoal. Ink proved a strict mistress. Drawing with ink is a one-way path.5 It wasn’t exactly fun, but sometimes I could access a flow state where the drawing seemed to make itself. Mind went away, and eye spoke to hand. I’d go into a trance, submerged in a universe of mark-making, and emerge at the end to see what I’d made. In this drawing-trance I couldn’t talk. Also, any interruption felt excruciating: the thread of the drawing was difficult to follow and easily lost.

If you do something consistently enough, evolution can’t help but occur. Dailiness ups the odds. A lot of the drawings were bad, but I made so many of them that my hit rate was high. Intertwined with the current of mediocrity was a steady flow of good work, with the occasional flash of excellence. Inspiration is a delicate flower, but daily discipline crushes it under the boot.6 Tomorrow, tomorrow, again, again, again, forever. (Fail better etc.)7

After finishing this project, I was left with a massive portfolio of drawings.8 In July of this year I decided to post a few of these daily drawings on Notes;9 the forms seemed a match. The drawings are little time capsules for me, memory prompts: I can often remember where I was, what was happening around me, how I felt, etc., so I wrote short pieces prompted by each drawing.10

Notes float for a while then slip under. It seemed like a good idea to fish my drawing-Notes out of the memory-hole and compile them into a more substantial form— this Post. I like the randomness of the drawing-selection (I chose by whim) and the freshness of the writing that happens when I’m responding to a specific drawing. (Text in bold is the original Note.)

Looking at these drawings, I can see a strong focus on organic subject matter: animals, plants, people. There’s also a theme of the back of people’s heads. I did draw a lot of faces, but for whatever reason, they aren’t represented in this selection.

The drawing archive exists in two parallel forms: on paper and in my mind. I carry the index of it inside my memory, this black and white record of a decade of my life. Compiling this post, I was tempted to add more drawings, but I mostly didn’t. I can start anywhere and follow multiple linked chains of relatedness— but there’s no end to that.

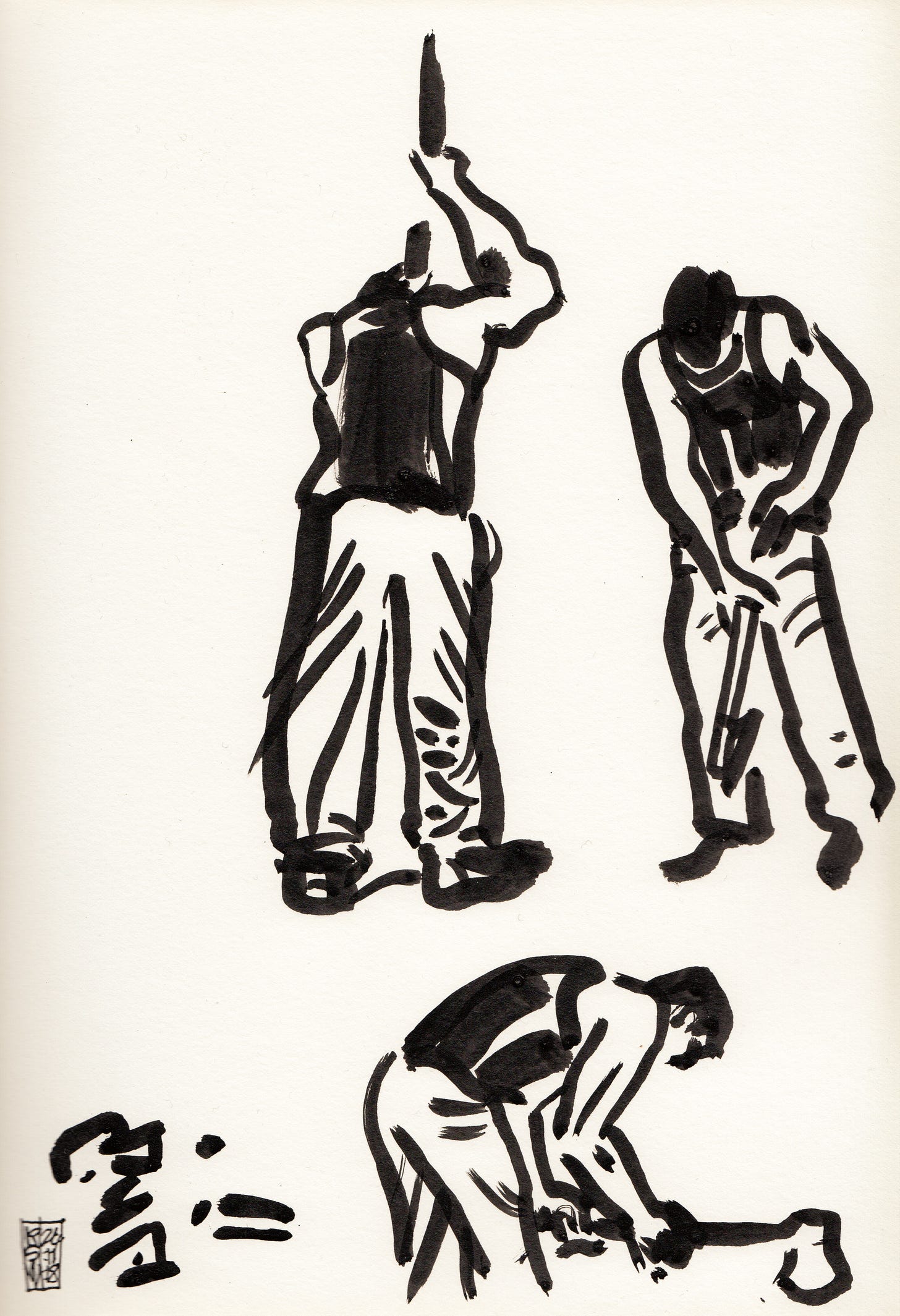

Woodchopping is a competitive sport in New Zealand, and the white trousers are a regulation garment.

I made this drawing sitting in the stands in the sun, drawing off the back of my camera. Drawing with a big brush is hard to get right— it forces stylisation. Very satisfying when it works. Then you have to sit there holding the book open until the ink dries.

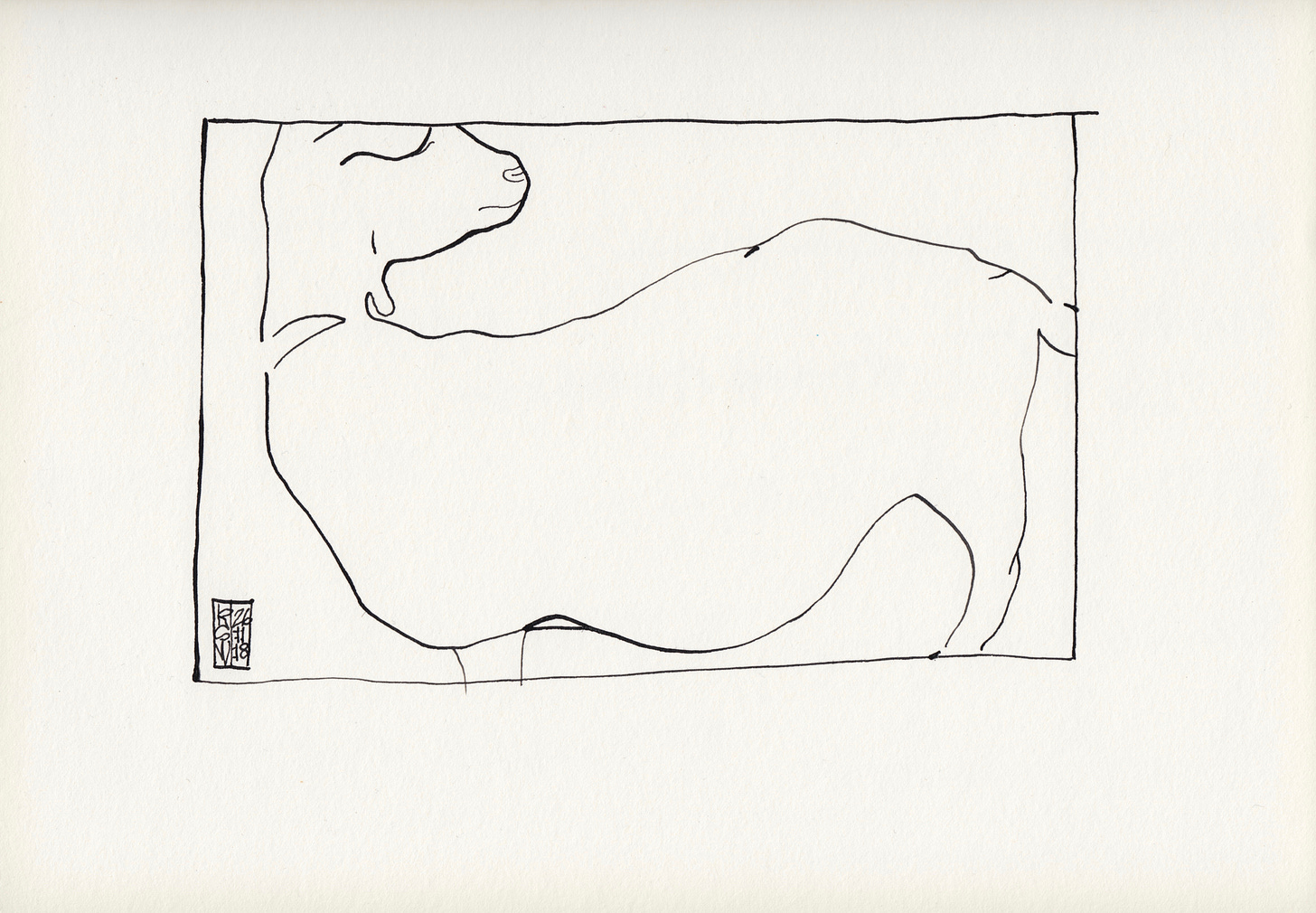

This is not the only drawing I did about the A & P Show;11 I also drew this Saanen goat.12

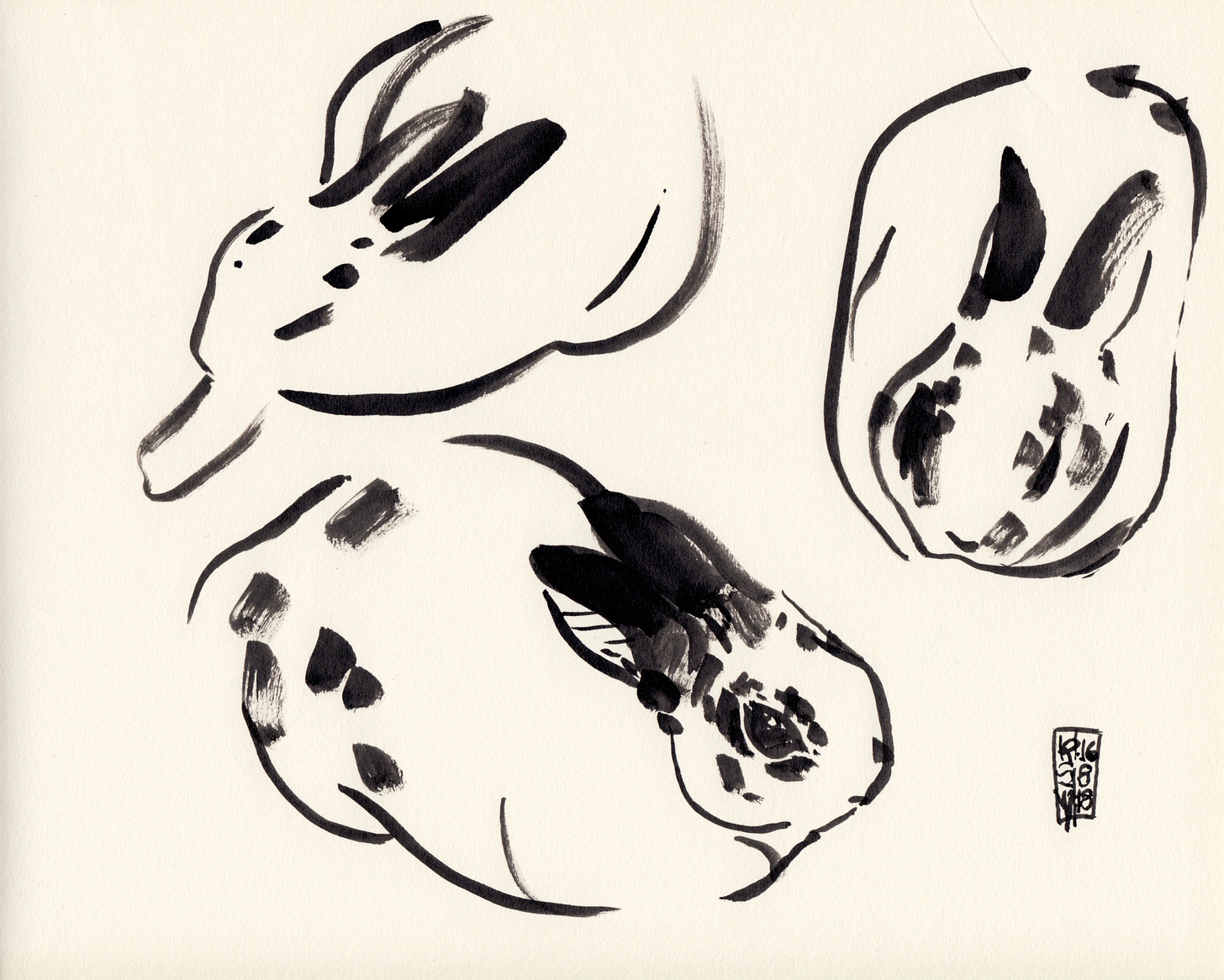

Champ periodically ran away to try to live with the wild rabbits, but they beat him up for being a black-and-white freak. I liked how his form in repose was loaf-like.

Drawn from life, hence the quickness of the cleaning-leg pose.

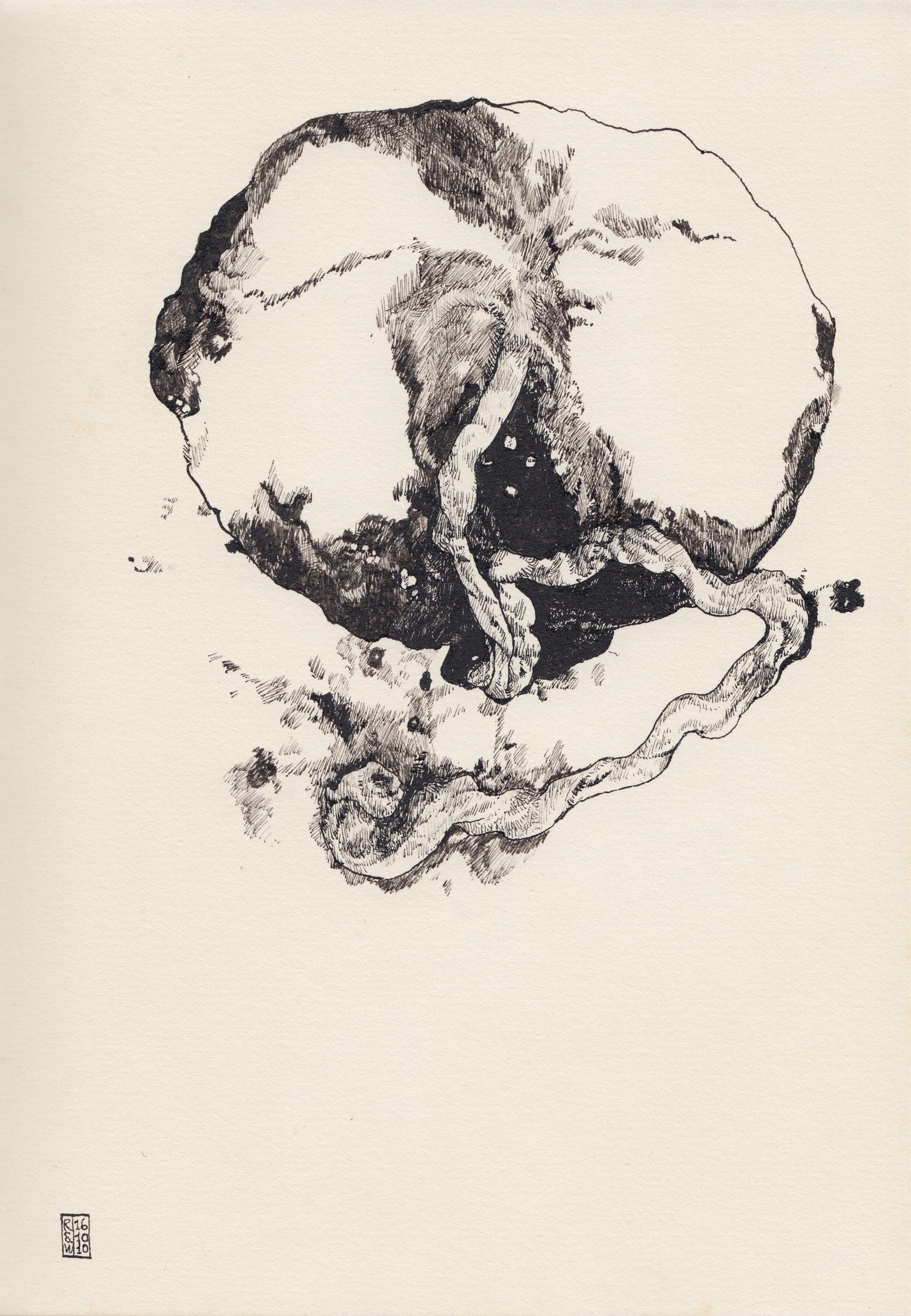

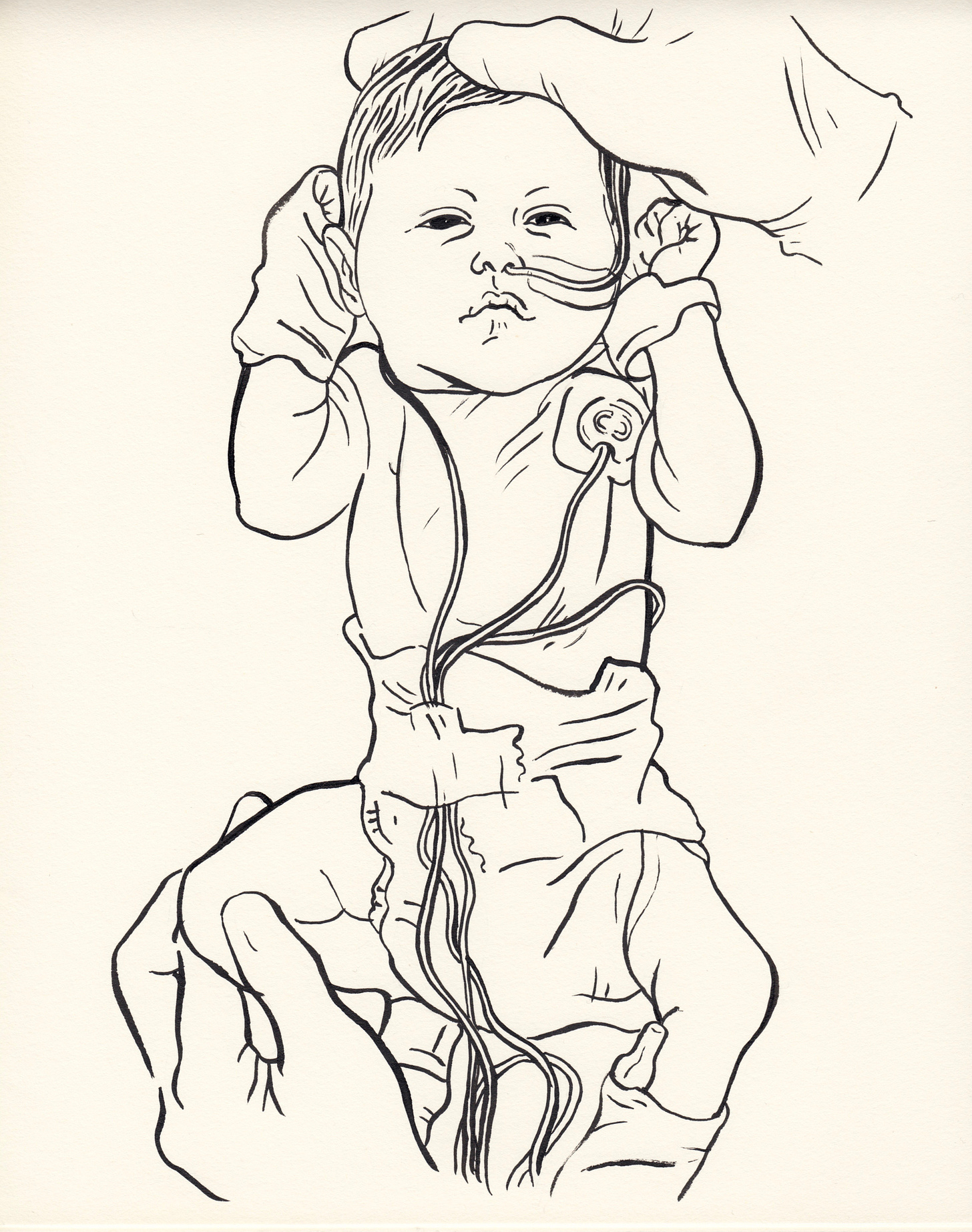

This drawing was made a couple of months into the project; I had recently discovered the tiny nib called a crow quill and I was making drawings that took four or five hours. This drawing was done from a grainy photo I took at a birth (maybe 1600 ASA). I was interested in the umbilical cord, with its complex structure. The drawing is incomplete, but I think it’s more interesting that way.

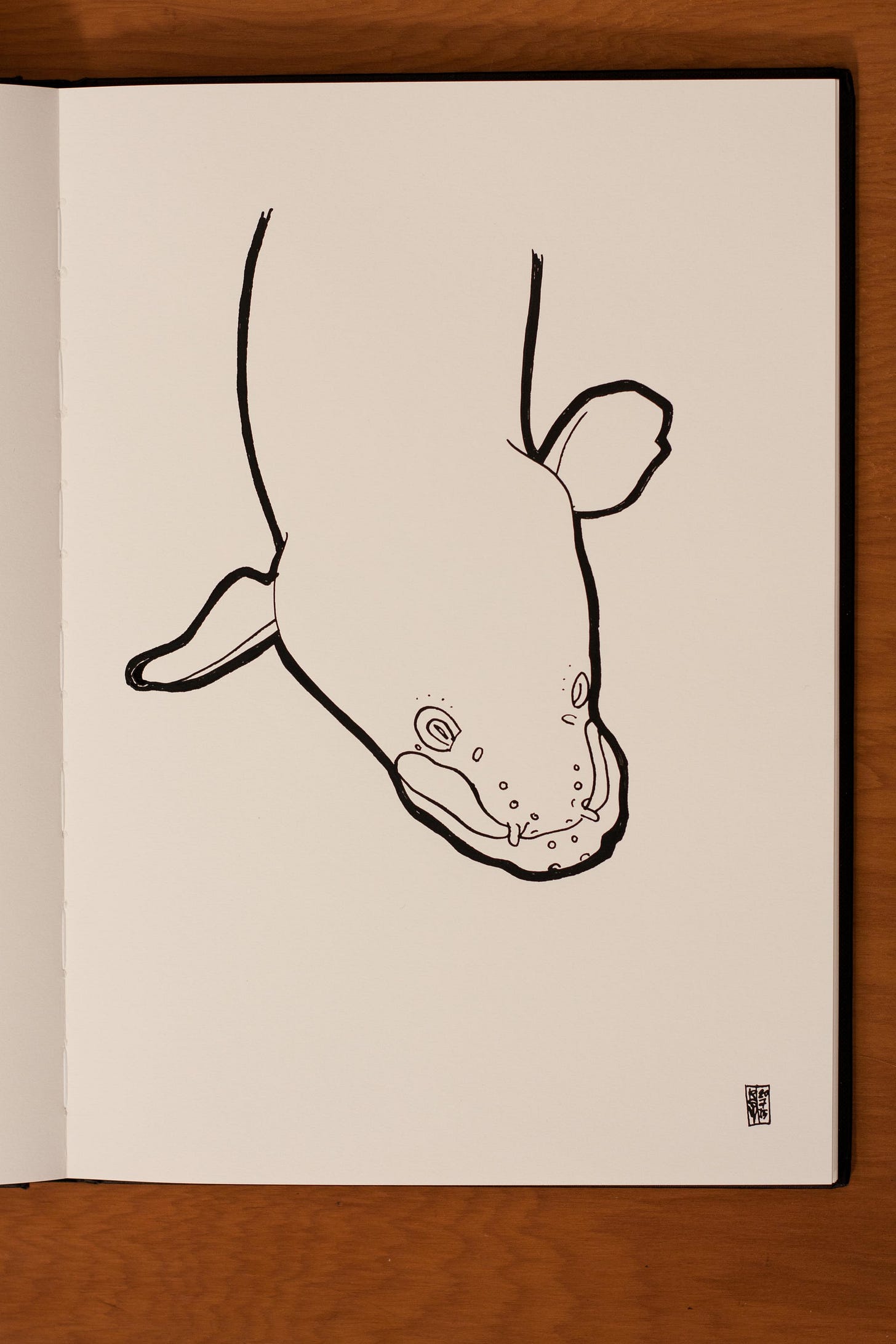

It was Christmas Day and Malou was determined to see some dolphins. This was a reasonable hope, as Summer is dolphin season on the South Coast, just as Winter is whale season. We walked down towards Red Rocks carpark (which was full of tourists lounging in their vans, cooking dinner etc.) and saw this seal playing near the shore. You can see the seal’s fin in the middle of the drawing.

During the Jurassic, Rhynchocephalians ruled the world: the small-reptile niche of it, anyway. Now the tuatara is the last surviving member of that order. Babies hatch with a ‘third’ parietal eye on top of their heads. Tara means peaked, thorny, toothed. The poet Harry Ricketts once told me how he used the tuatara that live at the University as a means of foretelling the day, depending on how many were visible of a morning.

I saw this one at Zealandia, the wildlife sanctuary, chilling outside its burrow. (In the wild, tuatara will sometimes share burrows with seabirds.) It was quite young, and so motionless and well-camouflaged that it was difficult to spot against the leaf-litter.

Dogs dislike to be stared at, so you have to work quickly.

I had been looking at Mayan stone reliefs from Yaxchilán. One panel showed Lady Xook doing ritual bloodletting by drawing a barbed cord through her tongue; then in the next panel a serpent rises from the bowl of (burnt) bloody paper and opens its mouth— out of the serpent’s mouth leans an ancestor, who speaks to Lady Xook. I thought this eel looked kind of like the serpent descending from above to dispense advice.

Eels have a supernatural vibe, in any case. The mystery of where they even come from was only recently solved: briefly, they transform themselves from freshwater to saltwater beings and migrate to sea to breed— Northern Hemisphere eels to the Sargasso, Southern Hemisphere eels to somewhere near Tonga; then the larvae return from sea to river, changing as they go from tiny transparent leaf-creatures into little glass eels, then brown elvers.

As well as the sensitive tubular nostrils, the dimples on an eel’s snout are sensory organs that enable it to sense vibes across distances, which is how they can appear with uncanny swiftness, following the trace of blood in the water.13

Plenty of people pointed out to me that this drawing has a phallic look— it hadn’t even crossed my mind.

I can’t remember this dog’s name, but I can remember its frenzy when we knocked on the door. It was whippet-shaped and mentally disturbed. Amos eventually calmed the dog by love-bombing. They lay on the couch together, belly to belly, which I can see clearly in my mind’s eye because I drew the two of them in that pose: I can see that the dog was black and white spotted with black ears. I can see Amos’ bowl-cut.

The house was in an olive orchard. I can hear the owner’s Italian accent as she speaks to the dog, but I still can’t hear the dog’s name, so I look it up in the back of the book: GINA. The true title of the drawing is ‘Gina in front of the fire’.

At a certain point I stopped scanning and photographing every drawing, so I don’t have an image of the Amos-and-Gina drawing to hand.

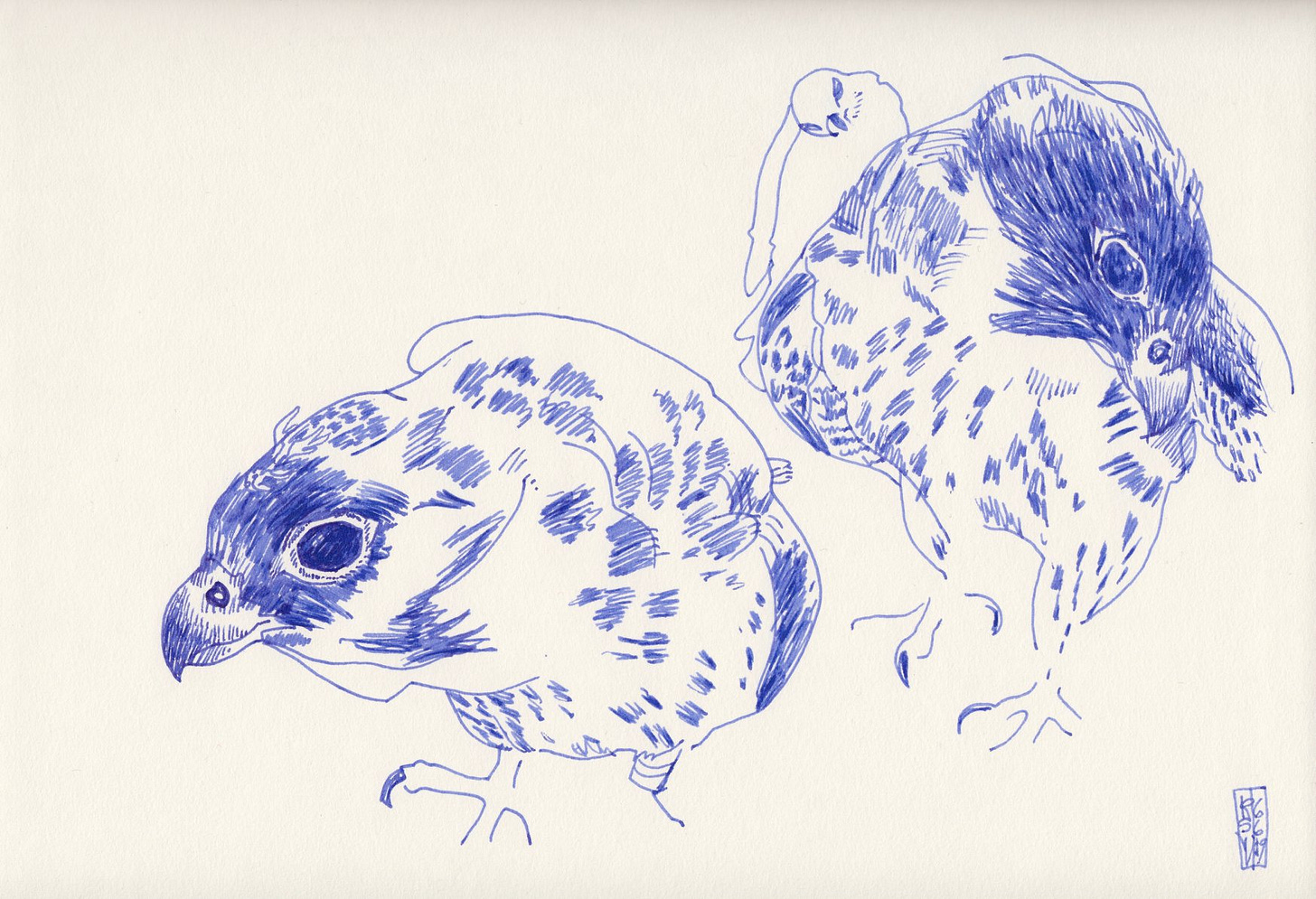

Drawn from a screenshot while watching the Norwich Cathedral peregrine falcon nestbox through a webcam. When I first discovered the falconcam, I made the decision not to find out anything about peregrines: I wanted to try to understand purely by observation.

This drawing is of the three teenage peregrine chicks, close to fledging.

A few more falcon drawings:

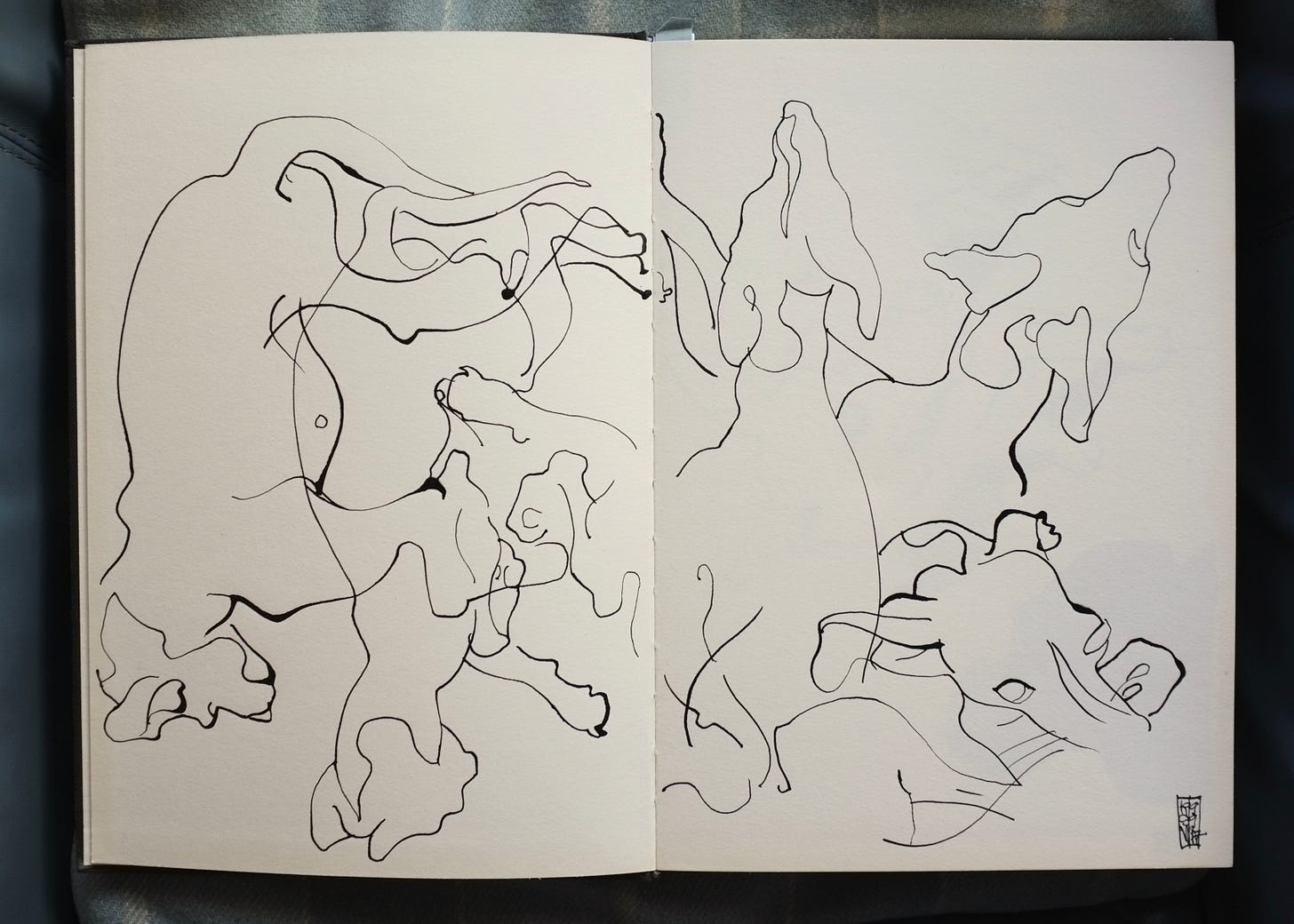

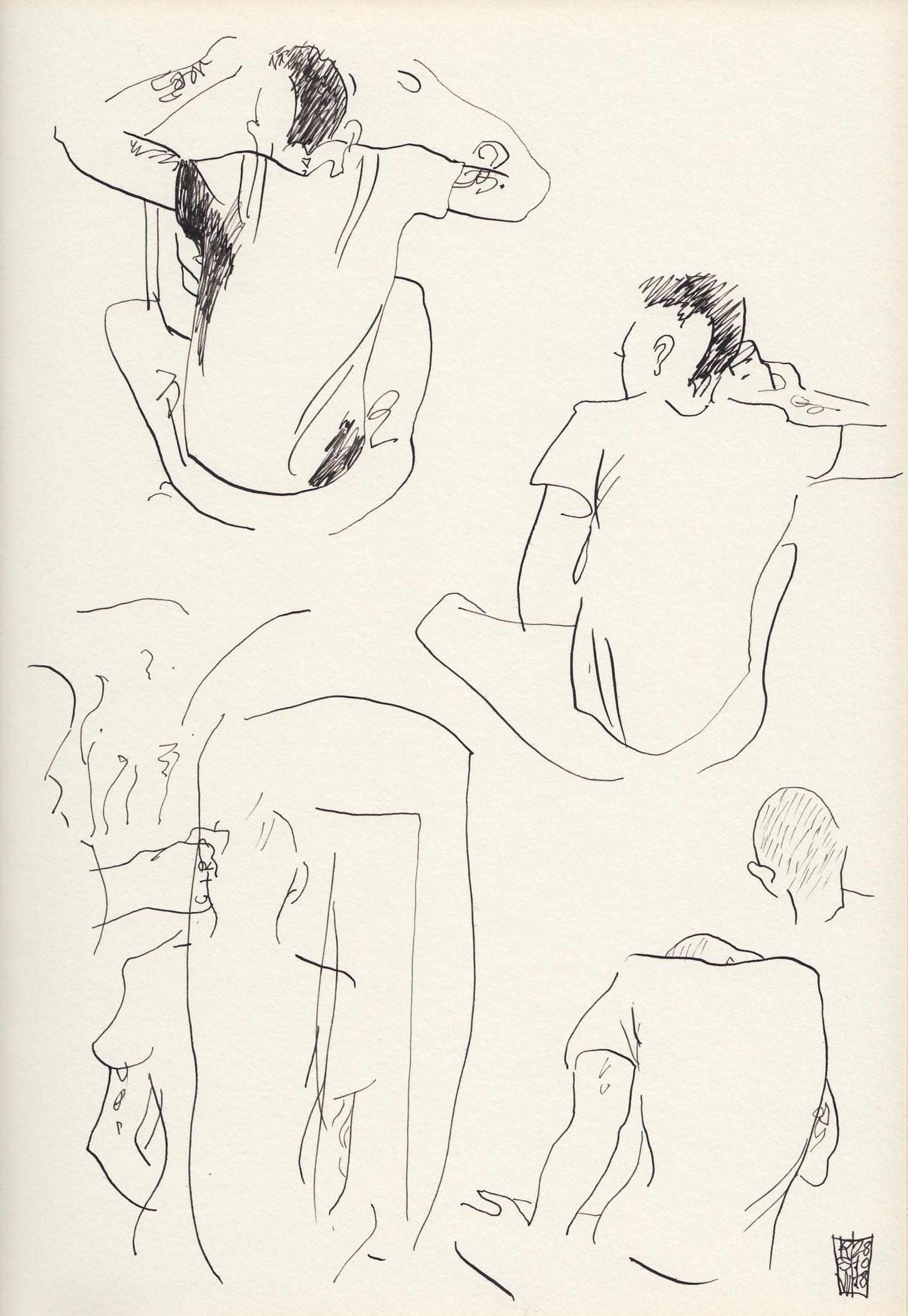

If I was ever proper drunk, I’d try to draw. It made it easy to be free and loose in the way I aspired to: a good blend of overconfident devil-may-careness and swift accuracy, like Jackie Chan.

I’d have been drinking whisky with my Dad. Drawn with a broad calligraphy nib, by the looks of it.

"I don't advise a haircut, man. All hairdressers are in the employment of the government. Hair are your aerials. They pick up signals from the cosmos and transmit them directly into the brain."

This is of course a Danny-the-drug-dealer quote from Withnail and I:

Brick fragments from the beach, ground by the sea into pebble-forms. I went through a phase of ‘scientific’ drawing: trying to render things accurately at 1:1 scale. I would place each object on the page and copy it. I never pencilled, so the layout was emergent. I had a little folding box of watercolours— each colour in its own little compartment— and a little hollow brush that folded away inside its own handle. I’ve found broken vintage watercolour pallettes on the beach once or twice: they are glazed white ceramic, with round depressions in them for colour-mixing.

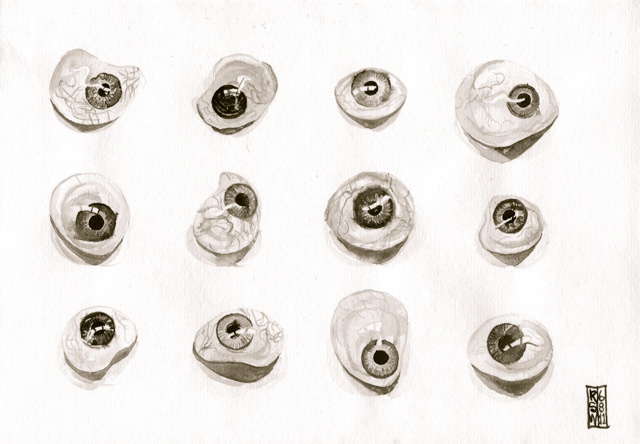

I call this format ‘list-drawing’. It’s very satisfying when it works. Another list-drawing— one of the flatmates at the house I was staying in, a Doctor’s child, had a set of glass eyes in a box with velvet-lined compartments. I spent a long time on this one, drawing with a small brush.

And another list-drawing, much later:

Drawn less than a month into first lockdown. Maybe there had been a storm, to throw these huge logs up? (Yes— on the 15th of April.)

Here in Aotearoa we had strict lockdowns that kept the country Covid-free for about two years longer than the rest of the world. Lockdown was an extremely strange time. From our safe little island, we watched the rest of the world going to shit. We wiped our groceries down. We cooked up big pots of bolognese. We drank boysenberry wine.14 We had driftwood fires on the beach, and sat by them singing apocalypse-songs to the accordion. (This one: Leonard Cohen - The Future15 …But also this one: Talking Heads - Nothing But Flowers)16 Looking at this drawing now, it conveys a sense of social distancing.

I found the suspension of ‘normality’ exhilarating, and I was hopeful that the unprecedented times would make people see— in the words of Ursula K. Le Guin— “that the way things are is not permanent, not universal, not necessary.” I was still a secret optimist, I guess; it seems decades ago.

This used to be real estate, now it’s only fields and trees. Where, where is the town? Now it’s nothing but flowers…

I was on my way home from one Bay to the other when I stopped to draw this. It was likely evening, I can’t remember. I started at the bottom of the page. I was intending to work my way up to the Island, but I got tangled up in the complexity of the foreground driftwood and ran out of room at the top. You will just have to imagine that if you lift your eyes beyond the page, there is a smallish irregularly mountain-shaped island with skirts of rock not too far out to sea. The island definitely has a vibe. Nobody lives there, although people do paddle or swim over from time to time. It’s mostly home only to seabirds.

You can see someone has made a small rock-stack at top right, probably Stavros Kyriakides, who roams the shoreline all day long rearranging logs and rocks. On the whole I disapprove of that kind of tinkering, but I respect Stavros as a fellow constant Wizard of the foreshore. Once we happened to cross paths when a humpback whale was breaching in Cook Strait. Stavros had been unaware of the whale because he doesn’t go on the Internet. We took turns watching through my spotting scope. He is prone to Wizsplaining, and sometimes from the bus window I see him buttonholing innocent passersby to enlighten them on the wonders of sealife.

There is a little film about Stavros, Rock-Paper-Scissors: you can watch the trailer here.

This is what I wrote about it at the time:

There were five quince trees in the orchard, all in a row. Of all the trees, there was only one where the blossoms were anywhere near open. They come in a kind of ice cream cone shape, spiralled up into a soft whipped white point, pink-tipped. There was one single open blossom on one of the trees. It was the very beginning of the particular quinceish phase of Spring right there and then. Like the very very beginning; not a single other flower open but that one.

After some deliberation I picked the second-most-open blossom to draw: its petals were just starting to unfurl. I felt a sacrilegious twinge at picking a fruit blossom, but last Autumn's quinces were still pungently rotting underfoot. Quinces are not a modern fruit. In the act of picking— the jar of the twig breaking— the petals sprang apart, the flower in a flash half-opened.

In drawing fruit blossoms two things happen. One is that the petals change and unfold almost before your eyes. It's like a butterfly when it's just hatched out of the chrysalis, pumping blood into its wings. The twig is drinking up the water like a thirsty animal to fuel the process. The crumpledness uncrumples. For plant-time it's massively swift, speeded up.

Another is you have to go deep, deep into the heart of the flower, into the jungle of pollen tentacles, that tiny explosive universe of bee-seduction. The quince blossom had anthers like I'd never seen before. Chunky, long, grooved. I felt like some big clumsy mammal out of my depth in insect-world.

I was using the ink I used to use when I first got into ink drawing: sepia and shellac, squid juice mixed with beetle juice, old-fashioned, and I found I was emulating the style I used to use, trying for pure accuracy, pure line, and I felt like Time was accordioning, that my self of ten years ago and my slightly more battered self of Spring 2019 were crossing over, that they were in fact the same self.

‘The force that through the green fuse drives the flower / Drives my green age.’17

(The second drawing is apple blossom from 2009, the year before I started my Daily Drawing project.)18

A commissioned drawing to illustrate a PhD about baby's experience of being in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. The gloved hand at the top represents the staff, and the hand at the bottom represents the family.

My only dissatisfaction with this drawing is that I don’t feel the baby looks newborn enough. Brand new babies are hard to draw because they are so formless: just squishy features in the middle of a big head. The eyes of this baby look somehow alert, which is not how most newborns look— though I have known some to gaze straightaway. I do feel, though, that the gaze in this drawing centres the baby’s experience, which meets the brief.

Unlike my daily drawings, I planned this one out with pencil first, to make sure all the medical equipment was correct. (My friend Anna, a paediatrician, commented “Accurate!”)

This is not a daily drawing, but I’ve included it because here you can clearly see the difference between my daily drawing style— which is mostly fairly loose— and the style that emerges in more worked drawings. A commission involving technical or specific subject matter generally means having to combine multiple source material into a single image: that means the layout and composition have to be worked out in pencil first, and that makes the drawing tighter. This client was happy with my work, but I had a few commissions where the client was dissatisfied with the more formal style I used. Basically, it wasn’t possible for me to replicate my daily drawing style when I was drawing to spec: my personal drawings were made freely from a single source, for my own purposes. Also, mostly, these clients weren’t paying much for what inevitably turned into days and days of exacting labour. Eventually I stopped taking on commissions, because I found the process too awful.

(I wrote in the comments) I love how they spiral up as they start to dry out. They dry and fade beautifully. These ones probably came out of my hair. I would’ve stolen them from a garden and stuck them in my hair, maybe on a Festival day!

Again, not an official daily drawing— it’s from my writing journal.

Antibiotics. Matches. Dried roses. Guitar pick.

I always felt like drawing in fountain pen was cheating because it was so easy: the portability, the continuous flow, never having to pause to dip into the ink. The roses were Cécille Brunner, likely picked from a hedge. I like their old-fashioned, slightly peppery scent. I had strep throat, caught from a child— I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy.

When I first got onto Substack I was resolved not to show my face. It’s like when I’m reading someone’s book: I try to resist looking at the author photo until I’m done, because I’m a mind-meld purist.

Ursula Le Guin says in her essay Telling is Listening “My private model for intersubjectivity, or communication by speech, or conversation, is amoebas having sex.” Then there’s a little hand-drawn diagram: two amoebas connected by a pseudopod-channel exchanging genetic information. She goes on to say “My model of printed public writing and of secondary orality is a box A shooting information out into a putative spacetime that may or may not contain many box Bs to receive it— maybe nobody— possibly an Audience of Millions… Transmission via print and the media is one-way; its mutuality is merely virtual or hopeful.”

(More on that essay here: themarginalian.org/2015/10/21/telling-i…)

Despite having spent hundreds of hours drawing people’s faces, I don’t really care that much what people look like (multitudes etc.). It’s the least interesting thing about them; the skin of the fruit.

Anyway, this morning I decide to switch up my previous profile photo (me standing on top of a driftwood tree-trunk on the beach: I chose it for its silhouette-ishness, which makes an image pop when it’s tiny, but I guess the literally statuesque stance and black face mask might have made it seem … unfriendly … to the casual observer) for an image that includes my face. The new/old image was taken on Midwinter night a number of years ago. I had spent the day constructing antlers out of driftwood (the most difficult part of the process was finding a matched pair), and I was about to wear them out for the first time, to a ceremonial effigy-burning in the city. The new/old photo is also very silhouettey— a very ancient silhouette indeed: I still remember the magical ripple I generated that Midwinter night, as I walked through the city with antlers on.

This drawing is a self-portrait wearing the exact same outfit as in that photo— driftwood antlers and Wizard coat. (More about the snake coat here: rosiewhinray.substack.com/p/the-many-po…) In the photo I drew this from, I’m at a seasonal Hallowe’en party at my friend Jen’s house. (Because we live in upside-down-land, all the Northern Hemisphere festivals are arse-backwards, so this was Hallowe’en in Southern Hemisphere Autumn-time.) Other-Rosie, Rosie Langabeer, is playing the piano, and I’m singing my favourite Tom Lehrer song ‘So long Mom, I’m off to drop the bomb’. Tom Lehrer - So Long Mom19

(Tom Lehrer is still alive— he’s 96!)

Cabaret singer is one of my future career plans. I’m saving it up for when I’m really old. Pretty sure it’s red wine in my cup. I brought home a party favour: a fake-blood-stained fake-hundred-dollar-bill with a certain orange President’s face on it, and on the back someone had written in blue ballpoint ‘Be the cryptid you wish to see in the woods’.20

There's a dead seal on my beach, a New Zealand fur seal. (There's a colony of them round the corner.) At first its pose made it look alive, but now it's blowing up like a balloon. A rotten seal is surpassingly stinky, so we have that to look forward to. Once I made a drawing of a dead seal. I think about how seals and humans are roughly the same size, and- I don't know if you've seen a seal's flipper bones, but they're quite fingerish. A few years ago there was a baby seal dead on the beach, and I watched its gradual disintegration into bare bones, which took some months.

This started as a comment on

’s post about seeing a dead seal pup. Here is a photo of a seal’s finger-bones:Later two men came with shovels and buried the dead seal on my beach. So far it has stayed buried.

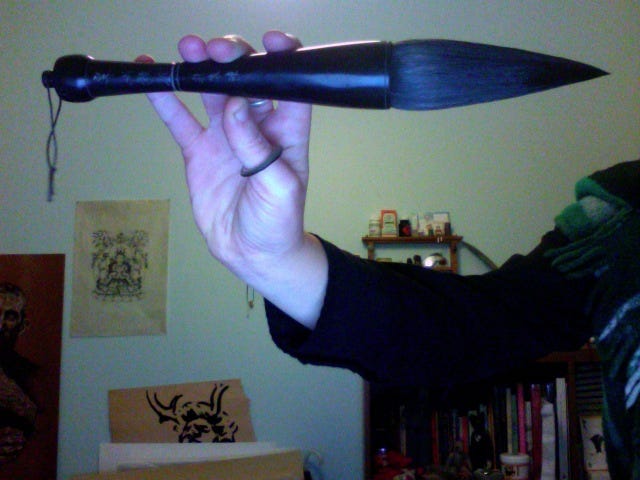

Brush calligraphy made with a magic brush given to me by Max Gimblett— The Brush of All Things.

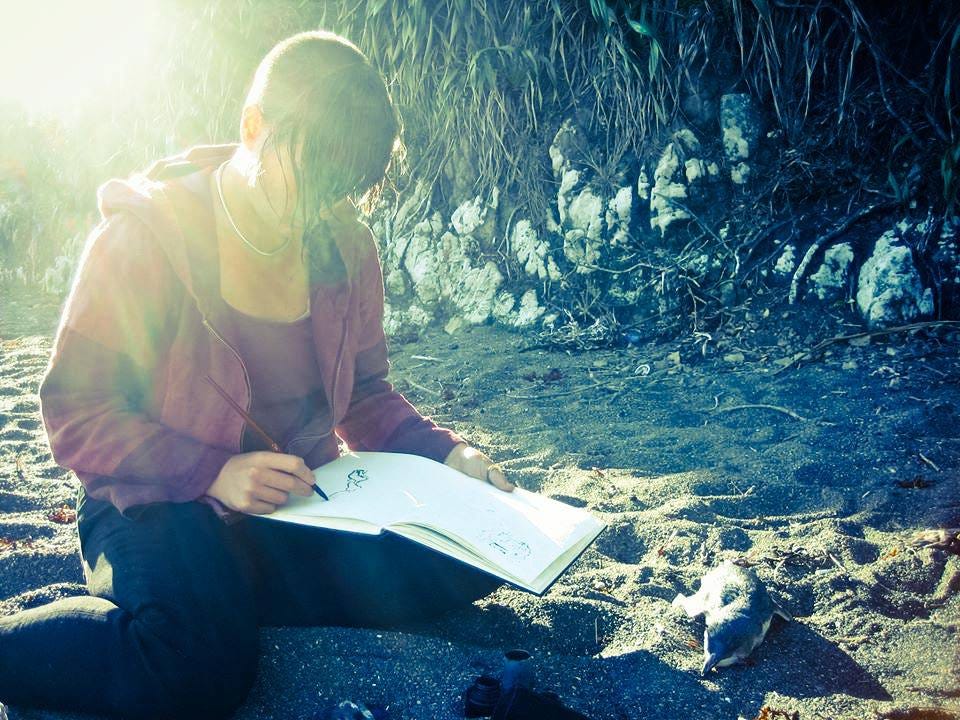

Drawing a dead kororā / little blue penguin at Breaker Bay in 2013. (Photo is by Su Keates.) My hair is wet from the sea. The penguin drawing was nothing to write home about, but here’s another dead seabird from 2010; I think it’s a petrel. My Mum brought it to me to draw. I had just discovered the tiny nib called the crow quill. I made this drawing in October, so just a few months into daily drawing.

I drew this in a phase where I would spend four, five, six hours on a single drawing. The placenta drawing is from the same series.

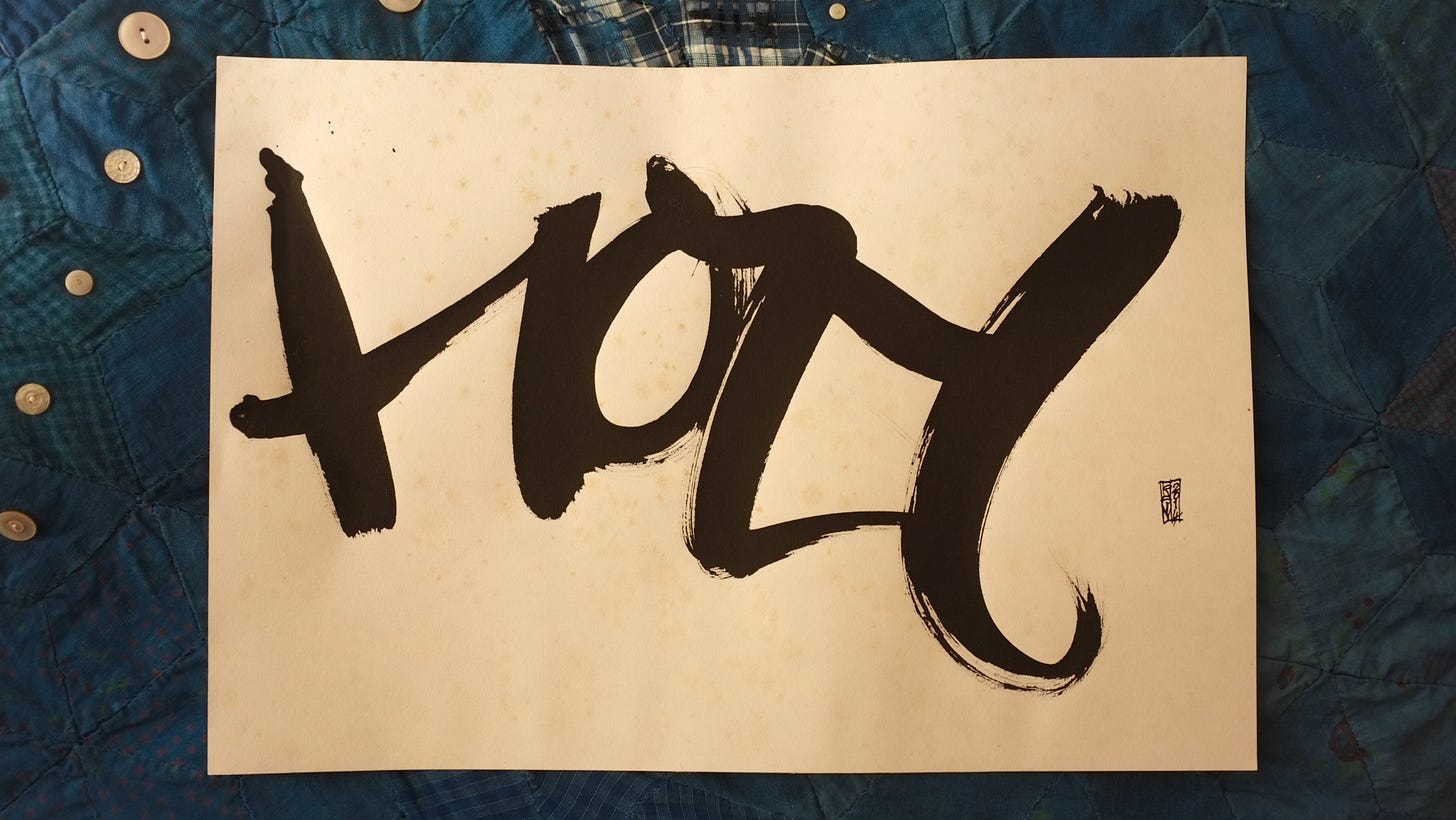

A nicely foxed calligraphy from 2014, found while unpacking / repacking the spare room. (I’m my own museum curator.) A Ginsbergian HOLY!

Allen Ginsberg - Footnote to Howl

Holy the sea holy the desert holy the railroad holy the locomotive holy the visions holy the hallucinations holy the miracles holy the eyeball holy the abyss!

Holy forgiveness! mercy! charity! faith! Holy! Ours! bodies! suffering! magnanimity!

Holy the supernatural extra brilliant intelligent kindness of the soul!

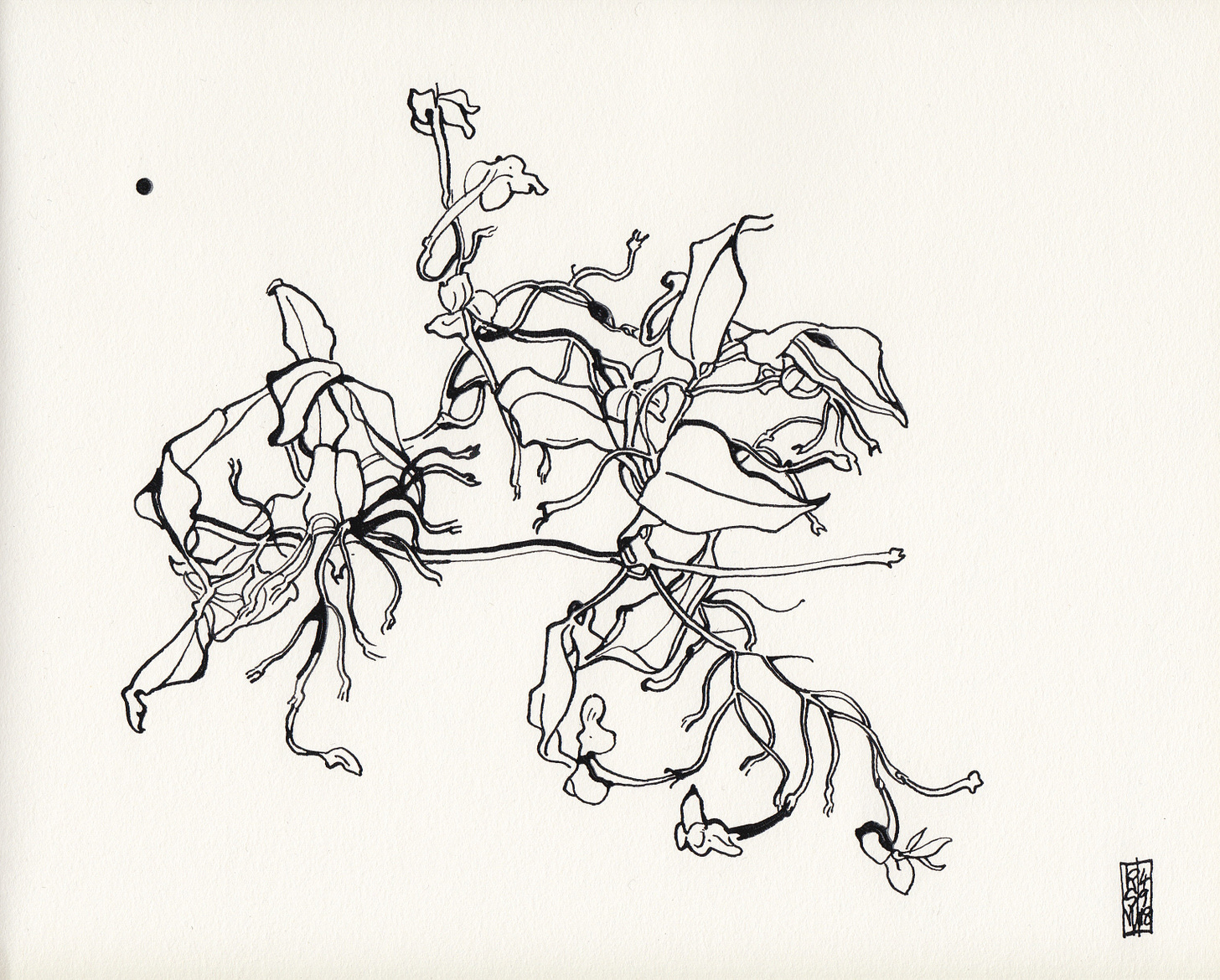

This is a drawing of a type I think of as ‘walking the tightrope’: start, keep going, keep going, keep going, finished. (As Klee famously said, ‘taking a line for a walk’.) Drawing this way feels trancelike. If you stop, you risk losing your flow and / or losing your way in the maze of detail. (I have a theory that botanical drawing provides the perfect level of complexity: only just graspable by the human mind. Drawings like this were traditionally a form of study. Every shape, every juncture, the particular texture of leaves and petals, every detail must be attended to in order to render with accuracy.)

When I was at high school and design school I was always in trouble for my attachment to drawing with line, but once I reverted to doing what I wanted without anyone watching, I realised that pure line is my language and my love. I love it for the same reason I love most of the forms I gravitate towards: it combines formal simplicity with technical challenge.

Another note about this drawing: my daily drawings often have encoded personal meanings— I’m not sure if they’re VISIBLE to others but I do feel they lend a drawing potency. This one was made in a Bad Time and I can feel in it my desire for a brief respite from thinking.

My favourite thing about it, though, is the effect of the glitchy nib, the way it randomly blots, fattening a single line or bridging the narrow gap between two parallel lines; not to mention that compositionally perfect ink-drop!

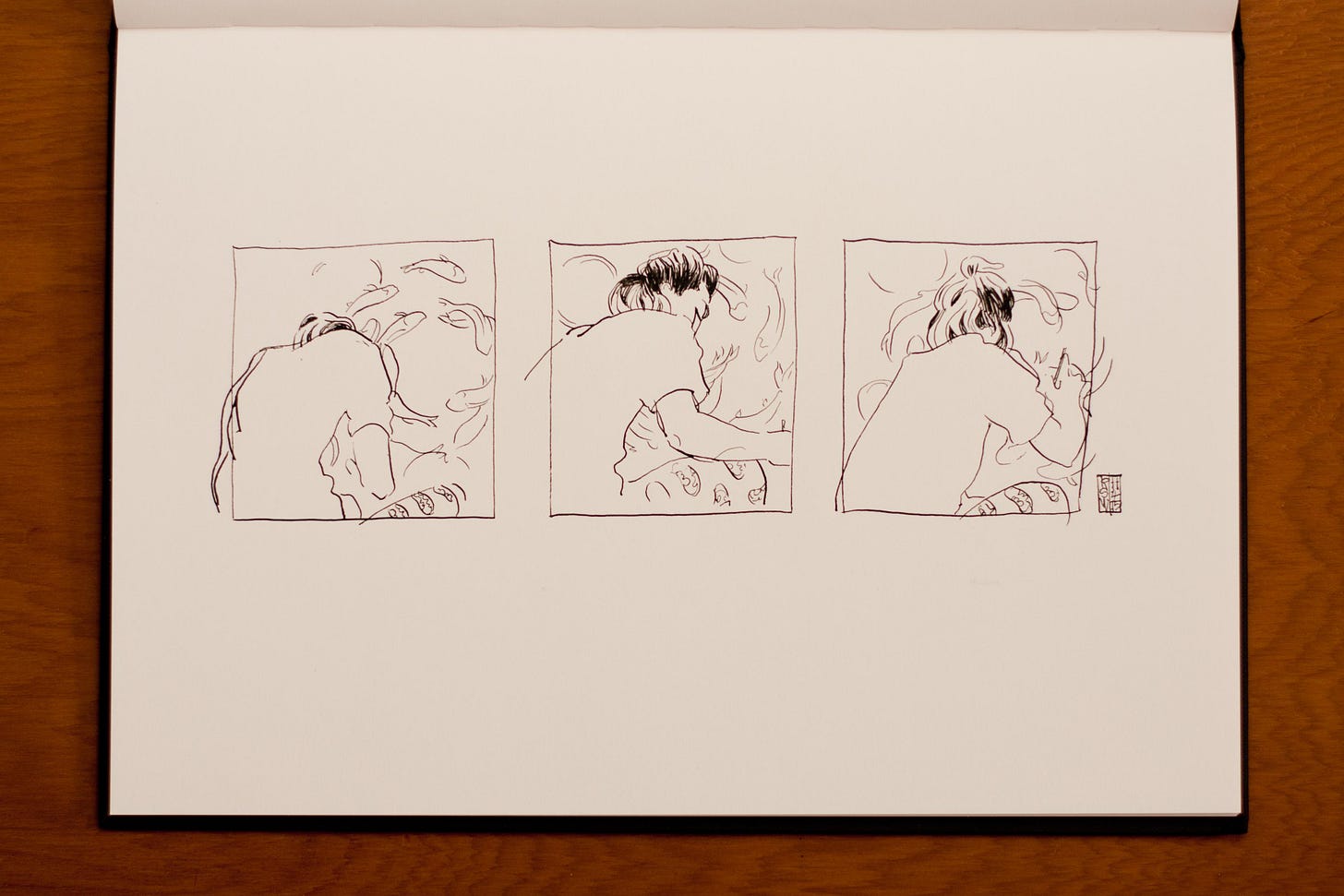

Drawn from life as my lovely flatmate Beau cut their hair sitting in the kitchen doorway in the sun. I would consider this a comic strip.21 In the third panel, a friend comes to help with the bits round the ears.

I initially intended the project to last one year.

I had a rule that the photos I drew from had to be my own, but I later relaxed that rule.

Again, I later relaxed this rule, using fountain pen and occasional watercolour.

i.e. Reproducibility

I could never eliminate a recurrent urge to press Undo; to go back in time a few seconds, erase the last stroke. To comfort myself, I held to the theory of the purposeful flaw. The minimalist style I developed was partly a result of wanting to stop at a good place: underdrawing rather than overdrawing.

I mean here the kind of sturdy walking boot that can take you over the mountains. The thousand-mile journey begins underfoot.

Samuel Beckett

I would estimate the total number of drawings at somewhere around 4000. Obviously 365 x 10 = 3650 (not accounting for leap years), but I frequently drew more than once in a day. There are 71 volumes. Each one has 60 pages— 71 x 60 = 4260— but some are half-empty (discarded if the paper was unworkable, for instance).

Notes are Substack’s short-form writing option, introduced a few months after I joined, I think to capitalise on the void left by the demise of Xitter. Notes don’t go out to subscribers by email, but appear on a feed viewed by other Substack-users. As such they are kind of a waste of time. I know that Posts are more important than Notes, but the ease and speed of writing Notes is a constant temptation to me— even more so at present: I’m meant to be doing something I don’t want to do— packing— so my compulsion to write and share is stronger, a procrastination-urge. I want / need to feel like I achieved something creative.

This was how I came to write my memoir-essay Three Times I Went to Christchurch: it was a Note about a drawing that got so long it became a Post. The drawing, japonica flowers in a cobalt glass bottle, was my Christchurch madeleine.

Three Times I Went to Christchurch

“There—there! That was worth a little bruise,” said the brown bear tenderly. “Some day thou wilt remember me.”

Agricultural and Pastoral Show, that is, it’s all about farming.

Kev had hoped to help milk some goats, because the goats are judged first with full then with empty udders, but the timing didn’t work out.

More about eels here:

Kev had made the wine in the days when he had scores of WWOOFers to make merry. (In Upper Moutere, boysenberries could be had for next to nothing at the end of the season.) When he came to Wellington just before the start of lockdown he brought the wine with him. There were four different batches in unlabelled wine bottles, so that you couldn’t tell which it was until you opened the bottle. Three quarters of it was boysenberry wine, ranging from sweet to dry, but one in four was the jackpot— a porty blackcurrant wine like adult Ribena. Lockdown was a boozey time. What else was there to do? Langabeer had a song she liked to sing: “I’m an alcoholic, I think I’ll get drunk tonight…”

Dylan Thomas

It was my friend Yvette, who I met that night.

Another comic drawing.

over Zoom. I often drew people reading, sleeping, watching things— anything that meant they were relatively still. Particularly, if I saw someone drawing, I drew them: meta-drawing.

I enjoy your writing and your sketches. They are inspiring. Thank you so much. 👏🏼🥰

Would you consider selling these? Or doing some sort of art exchange? I have the perfect spot on my wall for that quince blossom.