“There—there! That was worth a little bruise,” said the brown bear tenderly. “Some day thou wilt remember me.”1

This post features fighting, swearing, and drugs, so don’t read it if such things are likely to offend you.

It was the middle of Winter 2011, and I was in Christchurch for work. The roads were buckled and warped, the remaining citizens traumatised. My job was sorting out boxes of documents that had fallen down during the earthquake. Sizeable aftershocks rolled through every day, shaking my room on the second floor of an old villa-turned-backpackers. I didn’t have a car or an Internet connection, and the sore on my face that wouldn’t heal made me solitary. In the evenings I wandered around the neighbourhood playing mandolin in time to my steps until my fingers became too numb with cold to feel the strings,2 or I sat in my garret drawing with a crow quill, the tiniest nib, colouring in large areas with small strokes. Once I built a tower, now it’s done… Brother, can you spare a dime...

The old city was gone, smashed, but the new city was still in a larval form. Half of it was inaccessible, forbidden, and the accessible bits were littered with temporary barriers and rows of orange road-cones. As well as me, there were young construction workers from all over the world, there to turn a buck by putting things back together,3 and a secondary economy of hospo staff to serve them beer. (A young and shifting populace, four men to every woman, a pioneer-town ratio.) I had a per diem food allowance, which blew my mind— more per day than I’d usually spend in a week, and if I didn’t use it, it was gone— but there was nowhere to spend it except the supermarket and the organic shop. I kept thinking about how if I’d had that money in Wellington, I’d have dined like a King three times a day; but here in the broken city there were no cafés, no restaurants.

When I think about that time I see the photos I took on a borrowed camera. Tree-branches mirrored in puddles, their shadows overlaid. The loaf-shaped steel-and-glass conservatory in the Botanical Gardens, dusk casting dapples on its dirty panes. Flash glinting off the bent arrow of a temporary traffic sign. A small lake set into the lion-coloured grass of the Port Hills. A sunlit white bandstand behind chain-link. Black swans on the Avon after dark, kissing their reflections. I see myself reflected in Museum glass, wearing my old coat with the shield-shaped pin in the lapel.

I had only ever been to Christchurch maybe twice before. In my early 20s I’d visited my friend John in New Brighton: my first time in the South Island.4 The nearby swamp had a crust of thick ice, upon which we bounced pebbles. John had a small wood-burner in his bedroom— a thing I’d never seen— and I fell asleep watching the orange flames through the blackened glass door.

We went to the pools. (Going to the pools was a tradition dating from the time John made a vow not to wash until the upstairs bathroom was completed. He was living in a converted warehouse with a number of other hackers. They had built bedrooms for themselves by erecting partitions, but progress on the bathroom had stalled. He had a full-time office job at the time, and every morning he would wipe his face with a wet wipe and go to work.5 Was it weeks or months? I don’t remember. From time to time I’d coax him into coming to the pools for a spa, which didn’t count. His arms were black with grime; I felt sorry for everyone else, but it was necessary.) In Christchurch there were skinheads in the spa, ripped, swastikas and 88s tattooed all over their milky-white skin.

We also went to John’s friend Barf’s house. Barf had been arrested for car-related misdemeanours, which got him in the papers under the headline Teen Hoon Reprimanded. Barf and John were making a film called Welcome to Christchurch, You Fuck; the opening shot was raw sewage running down the footpath. At Barf’s, everybody was at the stove smoking spots. (Spotting: you heat two knives by jamming the blade-ends into the spiral element, then with one of the hot knives you pick up a tiny pre-rolled ball of weed and squish it between the two hot knife blades, while the spot-ee sucks the cloud of smoke via a large funnel, generally made of a plastic soft-drink bottle with the bottom sawed off. Big bang for your buck.) Barf’s house was a bare, teenage-boy flat with a half-eaten box of cereal on the naked table. The kitchen door was wide open. I looked up, and it was snowing. I had never seen falling snow before.

Then there was the time I went to Christchurch to visit Tom; another Winter. We met up with his new friend, Bodyslide Rose, a sex worker who Tom had met in the square. (He had a knack for striking up friendships: he was outgoing and hilarious, tall and dark. Women were always falling instantly in love with him, which I found tiresome.) Rose was trying to drain her husband’s credit card as a means of revenge. She took us to the most expensive restaurant she could find, which was French, and told us to order whatever we wanted. French onion soup, [something something], crème brûlée: the crusted cheese, the crunchy caramel. Rose told us about her bodyslide technique— slather yourself and the client in liberal quantities of oil and slide up and down on them— and what an arsehole her husband was. Afterwards we drank brandy and smoked fancy cigars.6 Once we were very drunk, Tom and I decided to confess what we found most annoying about each other. I told Tom that his Christianity pissed me off, and he told me that I was an insufferable know-it-all.7 Afterwards I tried to drunkenly crack a puddle by stepping on it, but almost fell over— it was frozen solid. We went home and got into bed, but Tom parted the blankets so that I was under the sheet and he was on top of it. We were strictly platonic, and the sheet thing was for reasons of chastity.

Another thing I remember: we were walking down the street— it was snowing— and a man said to Tom as he passed us, “Fuck her mate, I did.” Tom and I both wheeled around with full intent, like You wanna go, cunt? You wanna go? One or the other of us was holding an umbrella. The guy hurried away, yelling further insults over his shoulder. Tom and I were in a secret fight club at the time. I worked at a gym, with a sprung boxing ring and mats, and late at night, using my keys, we would sneak into my work with a select group of friends to spar. Tom practised a hardcore form of Kung fu that required him to beat his shins with sticks. Another red-headed friend was a Tae kwon do practitioner: I remember the way he sprang and leapt about. I would try to take them down, because the ground was where I had the advantage. We were healthy young animals.

(Also, when we were alone, Tom and I would punch each other in the face. Neither of us had been punched much, and we didn’t want to be shocked by the feeling in a future fight, so we practiced on each other. These experiments had to be undertaken in extreme secrecy, though, because Tom was a boy and I was a girl, and onlookers would not read what was happening as a feminist act. The point is, we were ready to go.)

My thing was submission-style groundfighting,8 the bastard spawn of BJJ that I was learning from my work-friend Steve, a big beardy Mediævalist. He had a very nerdy, unassuming look— fat guy with glasses— but he was a formidable fighter.9 He taught me about what to do if someone pulls a knife on you: you hold your hands up in an outwardly placatory but secretly defensive manner, and you do the opposite of them: if they hold the knife low, you hold your hands high; if they hold it high, you hold your hands low, ready to deflect a strike by a sacrificial block. Steve had a lot of good information like this. He taught me the sleeper hold, but I could never apply it painlessly, as he could. He had a big chunky man-arm which could gently nestle into both carotids and boom— unconscious. Tap when you see stars.

I loved Steve with a deep and pure love. There’s a flavour of trust that comes from sparring with someone who could easily kill you, but holds themself back; their restrained force calibrated to your learning, an indulgent tiger-parent. One time we were teaching a class together. We were in a grapple on the mat, demonstrating something, and he said OK, now kiss me. That seemed a little weird to me, but I figured he must have his reasons: maybe he wanted to defuse the tension. I kissed him on the cheek and he stared at me in shock, like what the hell?! TWIST me! I said twist me!10

But back to 2011. For once, I had company while I worked: there were four of us.11 One of the women I was working with told me how the quake had thrown her to the ground. She could hear her small daughters crying in another room, but couldn’t get to them: the quake’s force pinned her down.

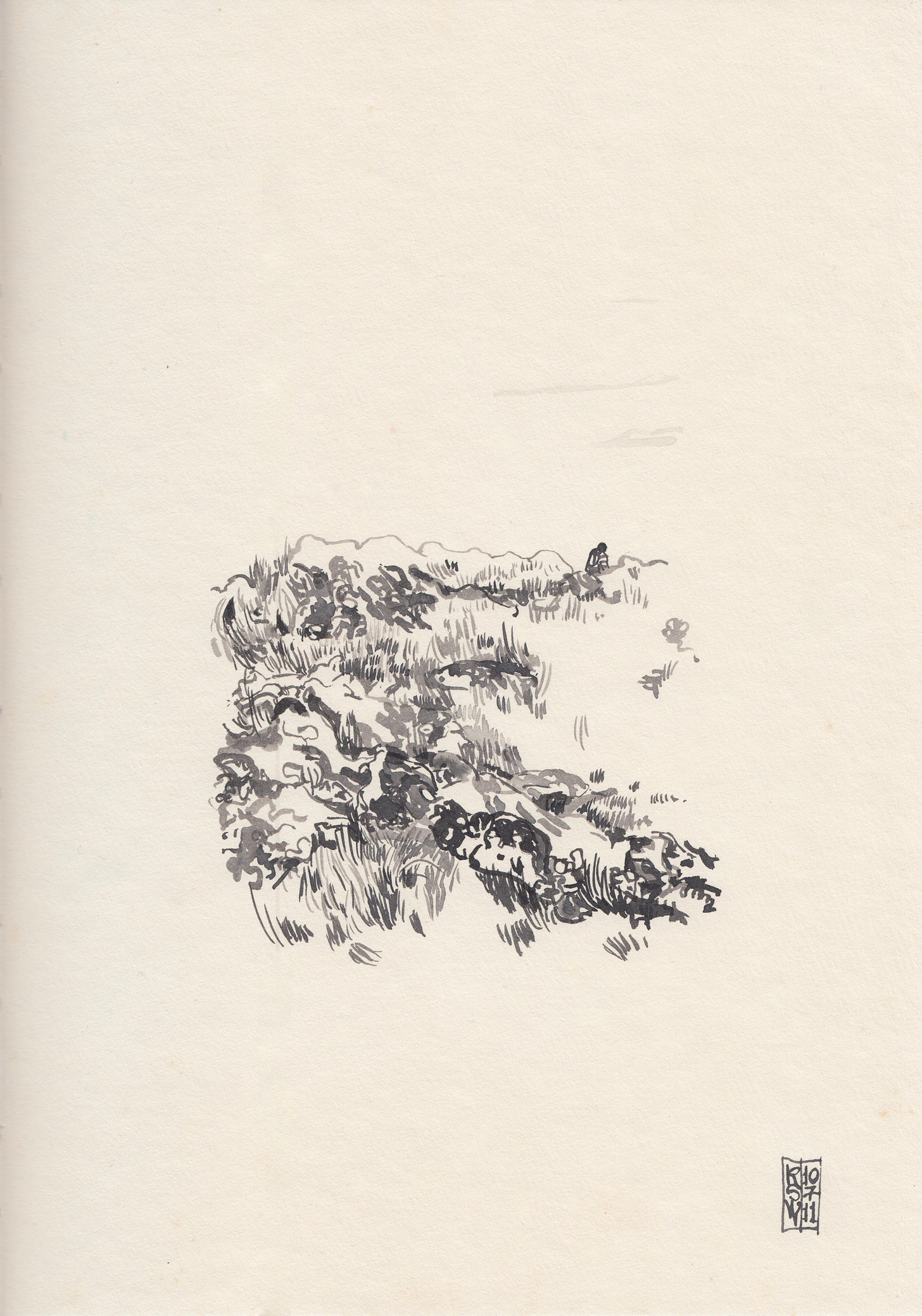

My other new workmate told me to call him Daisy. He told me his Mother was one of 17; that he never wore shoes, and preferred candlelight; that he had a weakness for bossy women. He said, The solution to your problems is drugs. His term for weed was magic box. Daisy had a car, and we drove up into the Port Hills. I’d never seen geology like that, the chunky stone cliffs dropping away towards Lyttelton. In the shadow of boulders, patches of unmelted snow.

I met a Chilean guy who had been in the massive 2010 earthquake in Chile: 8.8. He came to New Zealand to get away from all that, and was hit by the 2011 Christchurch earthquake: 6.3. (Magnitude isn’t everything— it depends on depth as well. In the same way everyone became amateur virologists during the Pandemic, they became amateur seismologists after the quake.) This same Chilean couldn’t understand why the Police kept pulling him over. It happened every few days. He had glossy black hair pulled back into a ponytail, favoured hoodies and sharkies,12 and drove a rusty old banger. I said “Bro, I’m sorry to say the cops think you’re Māori.”

At a party, I sang The Foggy Dew for some Irish people. As down the glen one Easter morn, to a city fair rode I.

The only civilisation in the new Christchurch was the container mall— literally shops inside converted shipping containers— which was on the far side of the Red Zone, the fenced-off area that had formerly been the central city. I could walk to the container mall on a weekend. It took an hour to get around the outside of the fence. I had to set out in good time, though: the days were short. The landscape was so flat that when night fell, it seemed to fall everywhere at once. With darkness came the bone-chilling cold.

A few weeks into my stay, a road opened through the middle of the Red Zone. The next weekend I set off to walk through the new shortcut. The silent buildings were eviscerated, their bones of steel rebar showing, wires dangling from the jagged edges of open rooms. It looked war-torn, bombed. I was the only pedestrian; a few cars passed at speed. Rubberneckers, boy-racers? Nobody else was around, and it felt lawless, a ghost town. 185 people had died in the quake, many of them here. Behind the tall chainlink the tumbled rubble was eerily quiet, empty of life, and abyss-panic came over me— too far out to sea. Get me the fuck out of here. The only way out was through. I walked faster. The light was already changing. When I came to the container mall it was almost closing time. I walked home the long way, around the perimeter.13

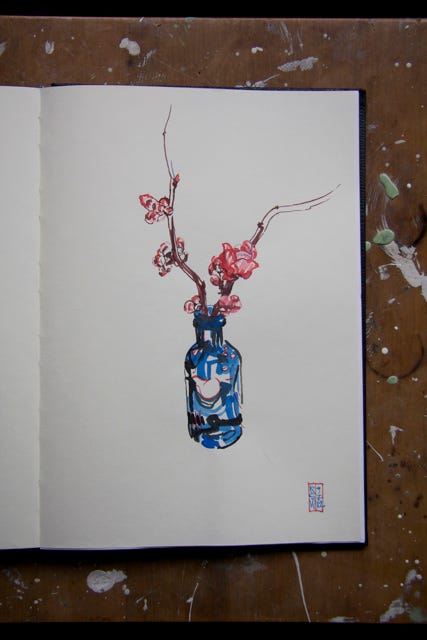

In someone’s deserted garden these flowers were blooming on naked branches. I took them home to the backpackers, put them in a cobalt bottle, and drew them using red, blue, and black ink.14 (I didn’t know their name then, but I know it now: Japonica.)

Both of these Christchurches are history now. The bad old one— where supposedly the Dalai Lama refused to get off the plane because he didn’t like the vibes— and the shattered post-quake city I visited in the fresh ruin of its colonial grandeur, an old socialite after a stroke. The new Christchurch was rebuilt into something else. Ōtautahi. What happened after the quakes radicalised people.15 Out of necessity, they were thrown into solidarity. The rebuild was an opportunity to experiment with making a better city: community gardens, social enterprise, experimental architecture. That’s what I hear, anyway. People I know buy houses there.

I remember this: behind a chain-link fence, a pile of timber that had been a grand house. Near the pile, someone had placed a small, ornate turret upright, like a playhouse, as if they couldn’t bear to smash it. It was painted in cake-icing colours, green and pink.

Rudyard Kipling, The Jungle Book

I hadn’t been playing long. I remember I was trying to master F, and the pop-strum down down-up up-down-up.

Deconstruction / reconstruction

Another mention of my first time in the South Island in this piece, about 1/5 of the way in: Through the Manawatū Gorge by Steam

All the hackers were basically unfireable

That shows how long ago it was. Smoking inside! I used to come home from the pub— my local, the Dog’s Bollix in Grafton, where Tom’s band The Muldoons played Irish pub music— with my clothes and hair reeking of cigarettes.

In Kev’s vernacular: Nobody likes a smart-arse.

Grappling is a useful form for young women. Men are often very reluctant to hit a woman, and scuffles tend to occur at close quarters— one is often just grabbed. Plus, it makes you strong all over, kind of like swimming.

Speak softly and carry a big stick, as my martial-artist Grandad used to say. Steve was also a pool shark, and had made money in the past by betting on games. When we played pool, he would handicap himself by playing one-handed: that is, he would hit the ball without lining the cue up along his knuckles, and sometimes he’d let me have two shots for every one of his— but he would still win.

I think of Steve every time I pass the spot on Breaker Bay where I was standing when I heard that he was dead. He had a heart attack inside a locked bathroom. His wife was a trained paramedic, but she couldn’t get in to resuscitate him. They had two tiny children who I saw for the first time at his funeral, a toddler and a babe-in-arms. Warriors crossed swords over him, and his coffin was a Viking boat.

Usually I would be alone in a basement or annexe, with person-high stacks of paper or roof-high shelves full of boxes to sort, which reminded me of a fairytale. Spin all this straw into gold by the morning. Sort the wheat from the stones.

Wraparound sunglasses

The ripple effect of the quake here in Wellington was that all the beautiful old buildings were red-stickered and yellow-stickered. (A red sticker meant immediate closure. Yellow meant that the building must be earthquake-strengthened within a certain number of years. Because the cost of strengthening is prohibitive, Wellington has become far less beautiful in order to become more safe.)

Wellington is the Quake City, and it was meant to be us— The Big One. Nobody knows exactly when Rūaumoko will kick or turn over, but there are probabilities. (Rūaumoko is the God of Earthquakes. In the telling I like he is unborn, and quakes are his stirrings in the womb of Papatūānuku.)

Including Adam McGrath— I talked about that here: On Being Galvanised, Not Paralysed.

I traveled from Texas to Christchurch in 2013-2014 as essentially a specialized contractor. Once in the summer, which was beautiful, and once in the winter, which was miserable. I worked in the devastated CBD, and in vast suburban neighborhoods of houses which had been condemned and purchased by the NZ government. We startled a few people, mostly older, who were still covertly squatting their own homes.

Much of the urban activity seemed to have re-coalesced in less-affected areas like the bustling Westfield Riccarton mall. I did visit the container mall for fancy keepsakes. The pub scene was thriving, but hard to investigate since we were working 7-day weeks. I was flabbergasted to stumble into an all-ages DIY punk showcase, apparently put on with the intent of giving kids something to do. This sort of scene had all but died out in my part of the world, 20 years earlier.

I vividly remember my time in Chch, and I appreciated this more intimate view.

Jeesus girl. That was awesome. Highest respect for not being a pampered sluburbanite.

I feel people like us were not born for this world. But for its ashes.

Do you ever pray for civilization collapse so you will finally fit in ?

I loved that piece.