T. H. White, The Once and Future King: “[I]n the old Merry England of Gramarye1… [t]he weather behaved itself.

In the spring, the little flowers came out obediently in the meads, and the dew sparkled, and the birds sang. In the summer it was beautifully hot for no less than four months, and, if it did rain just enough for agricultural purposes, they managed to arrange it so that it rained while you were in bed. In the autumn the leaves flamed and rattled before the west winds, tempering their sad adieu with glory. And in the winter, which was confined by statute to two months, the snow lay evenly, three feet thick, but never turned into slush.”

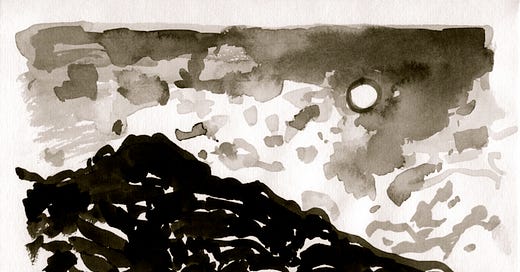

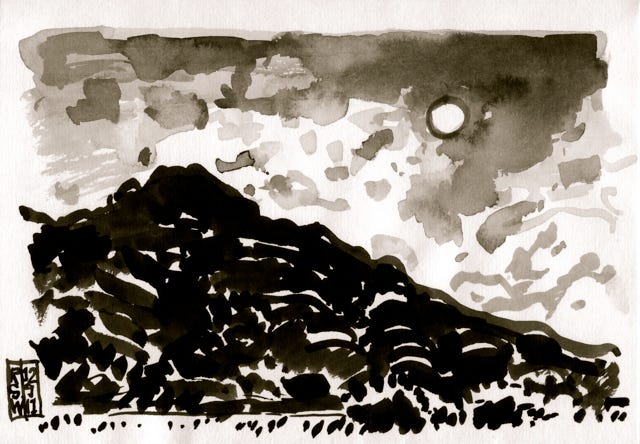

I went out for a morning walk. As I passed through my front gate I heard the first raindrops falling on the harakeke leaves, and put my umbrella up. The rain became an aura of sound-points on my small roof. By the time I got to the bottom of the stairs, I was conscious of the circumference of my umbrella’s dripline. My boots swung in and out of it, and stray drops fell on my satchel. I hate my bag to get wet so I picked it up and clasped it to my chest like a baby. Rain was hitting the stone-coloured sea, stippling it into a texture like octopus-skin. Fresh meets salt. I could see by the patterns on the surface how the rain swept across in stripes. By the time I got to the café it was pissing down, and I was hurrying, trying to minimise how wet my feet, legs, and back would be, manoeuvring my umbrella like a shield against the wind. Cars drove one by one into the flood at the corner, throwing sheets of water sideways. The horizon, the islands and headlands, all were gone, hidden behind a fog of grey. Waterworld.

It’s not the way of the samurai to hurry. In Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s Hagakure— as quoted by Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog— it says “There is something to be learned from a rainstorm. When meeting with a sudden shower, you try not to get wet and run quickly along the road. But doing such things as passing under the eaves of houses, you still get wet. When you are resolved from the beginning, you will not be perplexed, though you will still get the same soaking. This understanding extends to everything.”2

When I moved to the coast, thirteen Winters ago, I was working in a city office. When, on the first morning, I stepped out the front gate to wait for the bus, the wind and rain slapped me in the face, and I thought— What have I done?

On a Zoom call, someone from Sweden said that it had been a windy day, and they had welcomed it: “I never get touched, but now the wind is caressing me.”

It was quite nice, according to them. I was like Bro, move to Wellington and you can get freely wind-molested every day.

The sarcastic slogan people love to quote about this city— You can’t beat Wellington on a good day!— is a shadow reference to the weather. The joke is how few good days there are. Raukawa Moana / Cook Strait forms part of the Westerly wind-belt known as the Roaring Forties. Te Ika a Māui3 / the North Island, and Te Waka a Māui4 / Te Waipounamu5 / the South Island, are like the two claws of a crab, tucked beside each other. The North-facing claw, the top of the South, points up into the Tasman, towards Ahitereiria,6 while the South-facing claw— Wellington— points straight down towards Antarctica.7 That’s why Antarctic animals sometimes drop by.

When Kev was working on the orchard, his work was outside, rain or shine. He would step out the door like a diver, without hesitation. Then once, years later, he said to me, “I hate going outside in the rain.”

I was surprised. He’d never mentioned it before, and I had thought his stoicism meant he didn’t mind it.8

Weather means more in the country: it means, this is what we’ll be swimming in today. But it has gradations in the city, too, depending on things like what kind of house you live in and how you get around. It only takes one Winter under a leaky roof to rewire rain-sound from cosy to dread-inducing.

Last year brought weather-trauma on a much, much larger scale. I can’t stop thinking about James Shaw on Alice Snedden’s Bad News.

Snedden: “When the floods come, when the fatalities start stacking up as a result, which I presume will happen, perhaps not in our lifetime, but in the one—”

Shaw: “Oh no, it already has. You remember those floods and storms that we had last year— the Auckland Anniversary Day floods up there— people died in those floods, people died in Cyclone Gabrielle two weeks later as well. So we had climate change fatalities in this country. And we don’t acknowledge that very much.”

On Anniversary Day I was sitting in the front seat of the van in Kumeu. We had arrived at Auckland Folk Festival and parked, but we couldn’t leave the vehicle. The rain fell in waterfalls and streamed across the concrete underneath us. It fell and fell and fell. Many had turned back in the storm, but those of us who had made it through had to stay put. It wasn’t safe to leave the site, so we figured we might as well have a festival. (This caused trouble with the insurance later, because the event wasn’t cancelled.) Teenagers swam exuberantly in their underwear in the pool that the racecourse had become.9 When we sang in a circle inside a tin-roofed animal shed, I couldn’t hear myself, let alone anyone else, over the roar of the rain, and I immediately blew my voice out. Kev reported a green frog clinging to the side of the toilet bowl in the middle of the night. “We are that frog,” I said, “And God is flushing.”

Folkies love to reminisce, and I reckoned this would be a festival spoken of when the splashing teenagers were old and grey— I was there. If there were festivals by then. If they got old and grey.

As Henry David Thoreau said: “You shall observe what occurs in your latitude, I in mine.”

The weather is an observed, immediate phenomenon. Climate change comes to town. Remember that New Year when the light was weirded by smoke-drift from Australian bushfires, an eerie sepia cast over everything? There was nowhere to look away to, because the light covered everything in a tobacco-coloured haze. It was the first day of 2020 and I thought— We are in for an apocalyptic year.

When the going gets weird, the weird get going. On that day I resolved to come out of the Wizard Closet— to go public. It was the first of the first 2020, and I was 40 years old. That seemed a tidy piece of mathematics. If not now, then when? If not me, then who? If it’s the end of the world, then all bets are off.

On Sunday I went to Aro Fair. There was a man selling moss terraria, including tiny ones inside test-tubes to wear as earrings. I told him that my house is named The Terrarium. His hand-written labels said that the collembola— springtails— that live inside the glass-worlds need occasional feeding with a tiny grain of fish food.

There was a woman with excellent books of which I bought three, including Real Estate by Deborah Levy, which I’d read before and loved, and Joan Didion— I thought I’d give her another go.10

There was a stand with rat-traps, free to Aro Valley residents. It also had a tall black mesh-sided box sitting on a table. Inside the box was a branch of kawakawa: large green heart-shaped leaves filling the space. Someone was pointing into the back, and I thought the inhabitant was probably a wētā or other insect, but then I saw that the woman manning the stall had a bright green gecko in her hand. A flock of girls were gathered around, and she was asking their names and telling them they had to put away whatever they were holding in their hands before they could hold the gecko, as it would require their full attention.

Over the next couple of hours I circled back to the stall once, twice, three times. It was always busy. I stood around hoping to be offered the gecko, but I was ambivalent, because I didn’t think being held was necessarily a good thing from the gecko’s point of view. Because I didn’t put myself forward with enough conviction, it would be handed to people beside me, but not to me.

I went away and watched Jesse from the orchard drawing portraits. Have you ever had your portrait done before? Are you willing to sit for 20 minutes? Look at something, fix your eyes on it. If you need to move, that’s OK, just come back to what you were looking at. (Sets watch.) He was using charcoal powder and a brush to put in big soft areas of shadow, then refining with willow charcoal. His sitter was a dark-haired girl with red lipstick and a serene expression. I didn’t want to disturb him to say hi. It’s interesting to observe other people’s drawing processes; personally, I can’t abide to be watched. He was doing a good job. It was a good likeness, light-touch— suggestive rather than laboured. I like Jesse’s aura of calm intensity, shot through with flashes of merriment.

Barnaby came along with his friend and they stood watching Jesse too. They’d been at the last singing session. (“Blame my parents,” he’d said when he told us his name. I got the feeling it was a habitual phrase.) Barnaby had a record under his arm, and was reading a paperback. I asked him what the book was, and he showed me the cover: Master and Commander.11 When I said there was a good book-stall over there, he said that he had already bought three books— they were in the pockets of his coat. He talked about being weighed down by carrying too much in one’s pockets,12 and I said I guessed it was OK as long as the load was balanced, like a pack-mule. He pulled out his phone, which was a flip-phone: “Nice phone,” I said, and showed him mine. Dumb-phone solidarity!

He produced a Coke from some inside pocket— a weird Coke, long and tall, in a glass bottle, which he cracked open and started to drink. He told us how he’d bought one once with the label all in Spanish, so he couldn’t read it, but it concluded with a strong visual warning: he drank it anyway.

His friend was talking on her phone, trying to guide someone to where we were. How could it be so hard? It was a tiny fair. Then we saw the person appear by the stage: it was Biggs. “Oh, hello,” said Biggs to me. He had an LP in his hand. “I bought you a record!” he said to Barnaby.

”I bought YOU a record, too!” said Barnaby to Biggs. They must’ve both got them from Herb’s Mobile Record Store, a mint-green caravan. The album was— not exactly the Tijuana Brass, I can’t remember exactly what— but a retro, pastel, big-band type of cover.

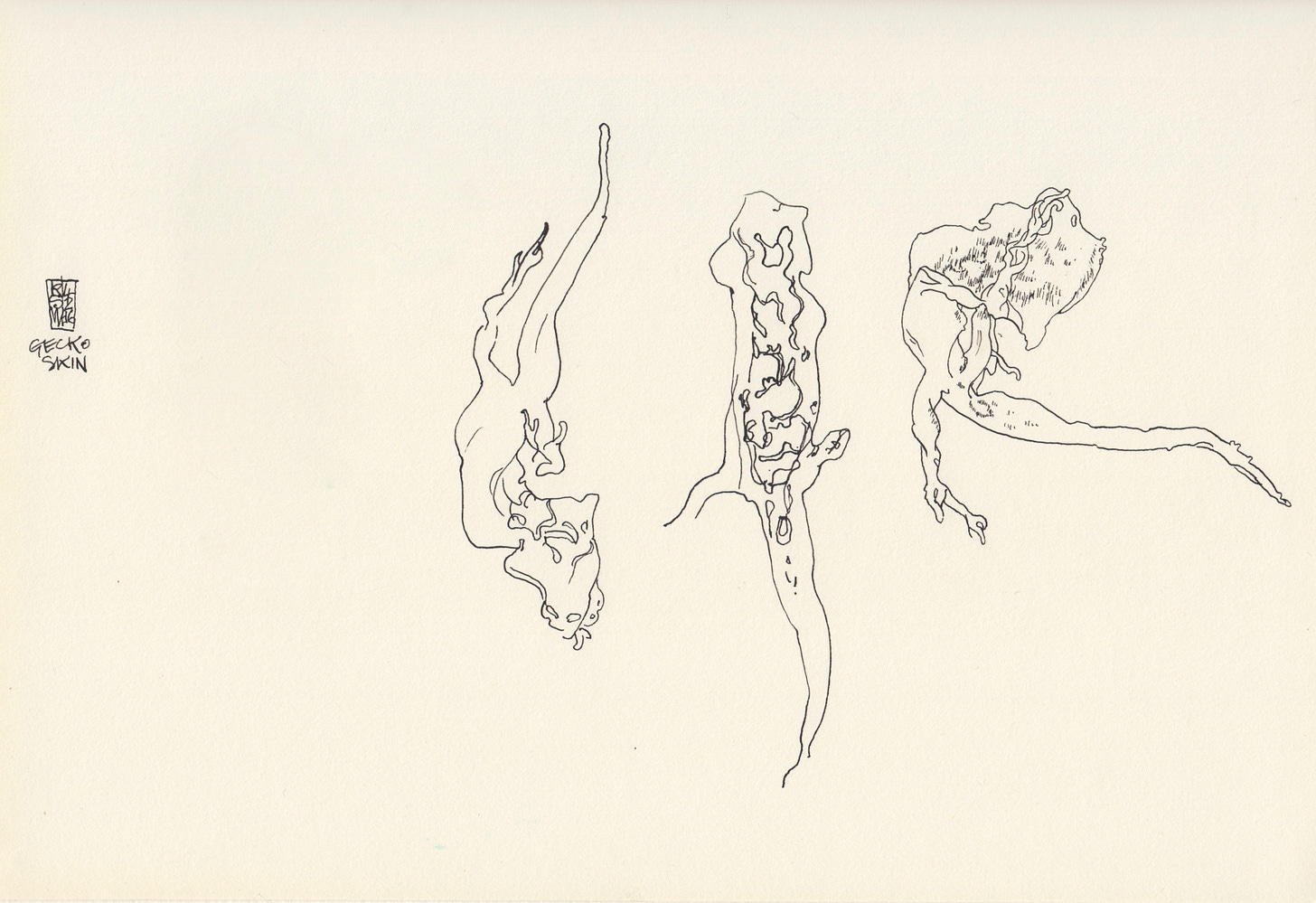

Jesse had finished the portrait and was spraying it with fixative. I gave him a quick hug between sitters. When he started drawing Barnaby— Could you turn your face away a little?— I drifted away, and came back to the gecko stall at a quiet moment. A youth was standing with the gecko in his hand. His face had that betwixt-and-between look of early teenagehood, when some features grow before others: maybe 13 or 14 years old. I looked into the box. There was one gecko clinging to the mesh near the top, grey, like a rock. I asked if it was about to shed its skin, but the boy told me that one was a different species.13 (I could see another green one hiding in the leaves at the bottom of the box, with its skin coming off, which was why I’d asked.)

Suddenly the boy holds the gecko out to me. “Put your thumb over the top of him.”

It climbs swiftly into my hand, then through my hand and onto my shirt, where it hangs over my heart. I shade it with my hand. It’s the first time I’ve worn this shirt, which I bought last week: sixties-ish green sprigs and white buds on a blue ground.14 Little dragon, little jewel! Green, bright as a lime, with white pixellated markings along its back and golden cat-eyes. When it puts its tongue out, the tongue is orange. Its delicate fingers are tipped with tiny claws. The creature is calm, and I’m moved. “So beautiful!” I say to the boy.

”Yeah, everyone who holds him says that.”

It’s breathing, the space between armpits and belly hollowing and filling. There is a small piece of unshed skin on one side of its head, like a fascinator. I let the gecko climb into my hands, and the boy takes him back and gives him to someone else, rubbing the lizard’s back affectionately with his thumb as it passes through his hands.

Me: “Doesn’t it stress him out?”

Boy: “Nah, I don’t think so.”

Me: “But how would you tell? I guess if he got really stressed out, he’d drop his tail.”

When I was a kid, our friends up North had a pet gecko. I remember its cage— a plastic oil container with one side cut out, filled with moss and bark and leaves. I remember the way it would drink, lapping up drops. And I remember it swimming, propelling itself forward with its tail. (Is that right? Did it swim?) It’s illegal to keep a gecko as a pet, but these things happen in the bush.

And I think of Henry with his gecko obsession, always hunting for them up in the mountains.

When I get home and look up the species, I find it is a Barking gecko / Moko kakariki:15 “Unlike other geckos, they can be aggressive and vocal when threatened.” So I guess if it was pissed off, it would bark. A good patting gecko, then. Easy.

The days are getting short, and when the sun goes away it’s cold. On the way down through Cuba Mall there’s a young busker sitting on the steps below JJ’s. He was playing real good for free.16 His guitar case is empty, so I throw a $2 coin in— all I can find in my bag— and sit down on a bench to listen. His guitar is small and dark and he’s thrashing the music out of it. At first I’m not sure if he can sing— maybe he’s one of those guitar-only players— but then he starts back in, and he has a good voice, low but not a bass, maybe a baritone, and he sings with conviction over the energy of his strum. He plays Johnny Cash, and some old blues, and Bankrobber by The Clash. It’s a good sound, honest, but the coins are slow to come. Cashless society. Tough crowd. His guitar and voice are unamplified and Cuba Mall isn’t busy. I know I’ve seen him somewhere before, but I can’t think where. Around town. At someone’s house. The busker takes a turn: Come Out ye Black and Tans. I join in on the chorus. Waiting for my Man. Maggie’s Farm. Fields of Athenry. His voice, warmed up, is hitting the higher register now.

After a while I notice how he’s rolling the songs out, pulling them out of his head one after the other, lyrics, instrumental breaks, and I’m impressed with his memory skills, which seem anachronistic. There’s this thing that happens at the moment: whenever I see a young person who seems old-fashioned— and I’m seeing it more and more, not just stylistically, but in action, in the way the young people are taking up old crafts, old ways— I feel a camaraderie. Mentally, I put them backwards in time, back to my own youth-time, or I wind back my own clock to imagine that we’re contemporaries now. I see them as a friend might see them. I’d be doing the same, if I were them. We’re united in the pursuit of anachronism, which puts us outside of normal time. There’s a word I’ve seen bandied around lately, chrononormativity— a term coined by Elizabeth Freeman— which means the expectation that we should progress through life in a timely fashion, doing the expected things at the right times. Outsiderhood, willed or unwilled, can remove people from this normative timescale.

A dude comes out of the Apothecary with a folded $20 which he must have got out in cash. He throws it in the case and the busker says “Thank you, sir,” but also, he doesn’t want to interrupt the driving rhythm of the song he’s singing, so he puts his foot on the guitar case and drags it closer, then puts his scruffy boot over the note. Luckily it’s not that windy, for once. When he finishes the song he starts to pack up.

Me: ”That’s more like it. Hourly rate.”

Him: “Yeah, that’s my night sorted! And I’m tired out now.”

I’m not surprised. Playing like that is an energetic workout, pouring oneself into the thankless evening crowd.

A year ago, I was polishing up my first Substack post— this one: The Pūpū Tarakihi / Paper Nautilus Method of Wizarding - On bespoke self-construction in the pelagic zone. I remember how long I worked to lick it into shape, the dive of hitting send. I started my ‘stack in the month before I moved house— from the Free Multiverse, the place I’d lived for over a decade— and the momentum of the newness carried me through that shift. This first birthday finds me at the tail end of a Lenten tech-fast, undertaken in unison with others I’ve never met, all over the world.

I wanted to publish this piece yesterday, the anniversary of my first post, but it wasn’t finished, and I have a rule of thumb not to post at night: let bright morning brain have a last look first. Morning brain is far smarter than evening brain. Then this morning this came through from

— a compilation of commentaries on the Lent fast. I append it here for your delectation: Sacred Synchronies: How to Restore Rhythms that Make us Human.Synchrony. Chrononormativity. Anachronism.17 See also: Chronic; Chronicle; Chronicler; Chronology; and Crony, an old friend. Not, however, Crone, which comes from Carrion— a carcass, an old ewe. Crone belongs to the word-family that includes Carnage; Carnal; Carnival; Carnivorous; Charnel; Incarnadine; Incarnate; and Scar. Crony and crone are false twins: a result of convergent etymological evolution. I’ll take meat over the clock any day.

Lit by the sensor light

a false-scorpion on the toilet door.18

Grammar, learning, erudition; occult knowledge, magic, enchantment; see also: glamour, grimoire.

Also, “Meditation on inevitable death should be performed daily. Every day when one’s body and mind are at peace, one should meditate upon being ripped apart by arrows, rifles, spears and swords, being carried away by surging waves, being thrown into the midst of a great fire, being struck by lightning, being shaken to death by a great earthquake, falling from thousand-foot cliffs, dying of disease or committing seppuku at the death of one’s master. And every day without fail one should consider himself as dead.”

Māui’s fish

Māui’s canoe

Greenstone waters

Australia

Denis Glover:

”At one flank old Tasman, the boar,

Slashes and tears,

And the other Pacific’s sheer

Mountainous anger devours,

Sings Harry in the wind-break.”

I check this story with Kev and he says that it’s true that he hates going outside in the rain, a legacy of doing his teenage paper run underdressed. But he also says that while he was on the orchard he didn’t necessarily have to work outside in wet weather, because there are a lot of orchard jobs— spraying, mowing, pruning— that can’t be done in the rain: he often worked in the cidery on a wet day.

It’s not a good idea to swim in floodwater, kids

Overrated. Maybe she’s just culturally irrelevant— too far removed from my world. I do understand why people love her so much, and the movie about her on Netflix is excellent.

I recently had cause to watch a scene from the movie, when I was learning this song for Hamsterfest.

I thought of the boy on the train, too: https://rosiewhinray.substack.com/p/the-many-pocketed-animal

I think maybe Mokopirirakau granulatus. Geckos are quite variable in their coloration: this one was liveried in subtle cloudy greys, just like a stone.

Made by Rixon Groove, a now-extinct Wellington shirtmaker.

Joni Mitchell, o’course:

Down with the tyranny of the clock! Help me punch Chronos in his fat face!

God I love this.

With every read, I feel like I'm there with you. Happy writing anniversary. Long may it continue xxx