The Hitchhiker

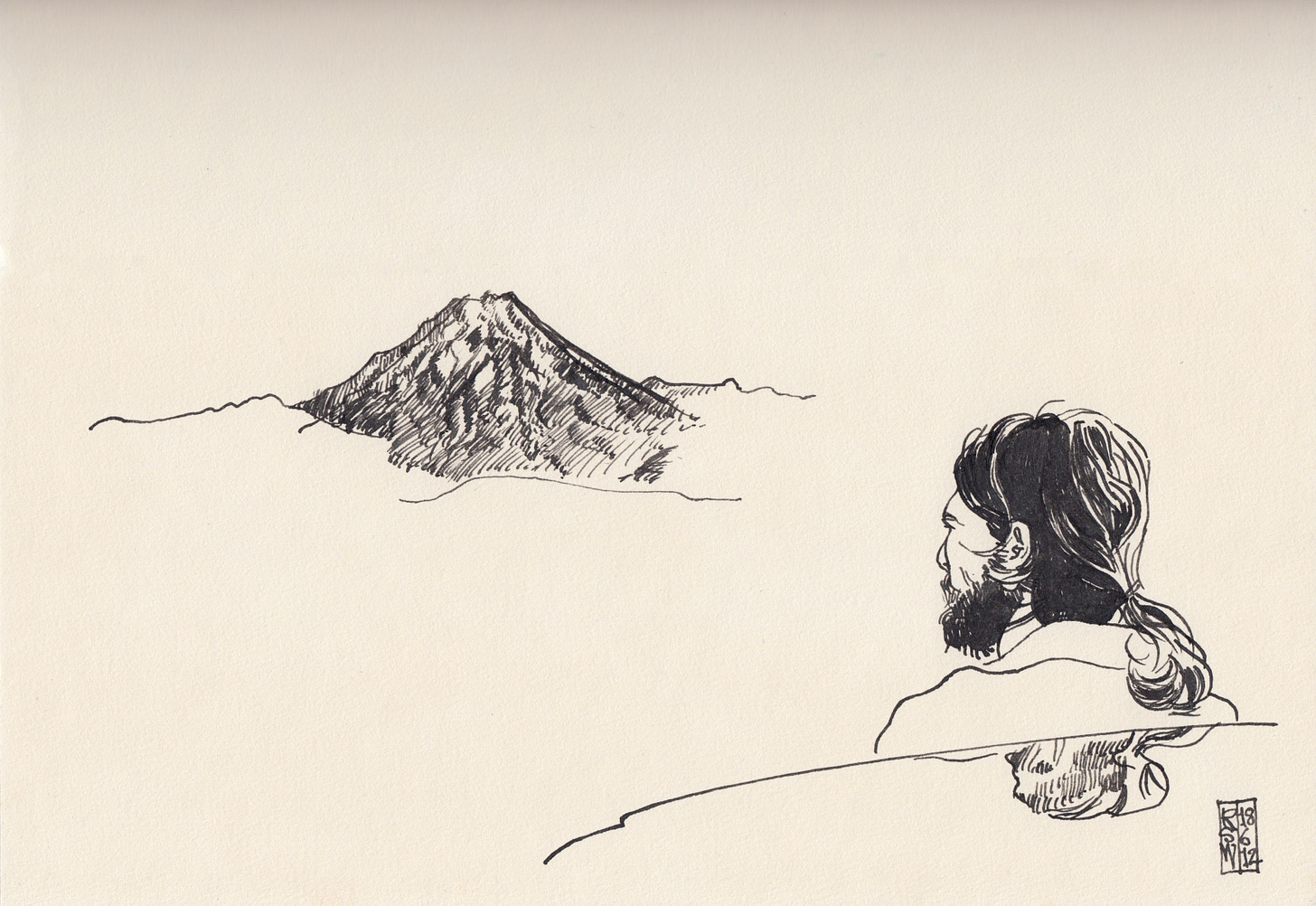

Taumarunui Gothic

This is another of those line-stories, the kind that unfold themselves by re-travelling in memory; but this one concerns a road driven, not a path walked.1

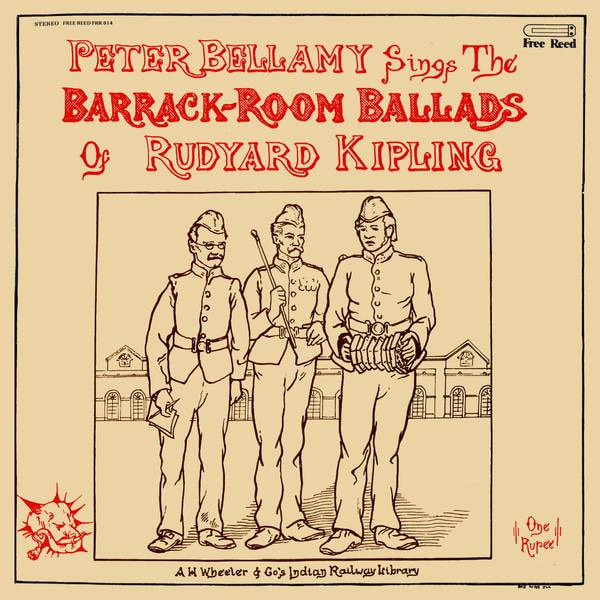

It was early afternoon and we were halfway home. Kev and I were listening to Peter Bellamy singing Kipling as we drove through Te Kūiti.2 The hitchhiker was standing at the T-junction on the far edge of town, facing down the long stroke of the T into the oncoming traffic. It was a judicious placement, and he stood there as if he was in no great hurry, as if he had stood in that spot many times before; as if he were waiting for a bus. In the few slowed-down seconds as I indicated to turn I took in his tweed jacket and brown hat, his bag and rolled umbrella on the ground. As I turned and pulled onto the shoulder, saying to Kev, “I’m going to get him, OK?” I saw that his hair was dyed chestnut with a good inch of white at the roots, and the whites of his eyes were red; set in that grey day they seemed to glow like coals.

I got out to rearrange bags and boxes in the back to make room for him to sit down, and he told me that he was going to Taumarunui, and when he opened his mouth I saw that he had a gold tooth at either side of his lower jaw, crowns rounded like nuggets in the river. As I indicated and pulled out I caught movement in the rear view mirror: he was throwing the headrest over the back of the seat. I turned the music off, embarrassed at the strangeness of it to an outsider— Barrack-Room Ballads indeed!— but as it turned out, I needn’t have bothered.

We passed a local beauty spot, a small waterfall that drops like a rope of silver hair beside the road, and the hitchhiker remarked how when he first came he used to drink the water from it, but it wasn’t very good: “Too many bits.”

Now he got his water from the springs at (X). Did we know the springs at (X)? When I said we didn’t, he was astonished. I asked him if he was English, by his accent. He said he had been born in the U.K., but most people guessed he was South African. When I tried to speak to him I realised he was very deaf. I had to turn my face and even so, he would cup his hand behind his left ear saying “Sorry?” Even if I yelled, I found, he mostly couldn’t understand me, and I had to keep my eyes on the winding road, to trace its tight curves. I covertly studied his face in the mirror. He sat there with the air of a lord. Ruined grandeur, like a mansion half-fallen, a kind of craggy Ted Hughes look. He had been handsome, I thought.

He told us that he had been at a hospital appointment— there was a hospital bus, but it didn’t stop at any intermediate stops, only the towns, and he lived somewhat out of town. I had already resolved that I would drive him all the way home, even if he lived somewhere out in the country. The wheel of hitch-hiking karma decreed it. I told him that I had hitch-hiked a lot, and that’s why I always pick up hitch-hikers. “When you were at University?” he asked.

”More or less.”

It was good, I said, that he was dressed smartly— a tweed jacket and a hat was cunning attire. Tidy. Not like all the other riff-raff.3 Drivers make a snap judgement of you in a second or two as you stand there by the roadside, so presentation is important. He said that it was easy to get picked up as a girl, all you had to do was put on a short skirt. I thought Whyever would you want to do that? That would be asking for trouble.

He told us he had to get home because he cared for a small boy. How old is he? I asked. Sorry? HOW OLD? “He’s nine tomorrow. It’s his birthday.”

I said that it had been my birthday yesterday. He asked me if I got any presents, and I said I got a bottle of whisky, but I don’t think he heard me.4 I wondered if he was a thief; but if he was, there wasn’t anything within reach, as far as I could tell.

I wondered who this child was— how did he get hold of a random child? His Grandchild? A foundling? I imagined a remote house, hillbilly scenarios. But as he continued talking I realised that the boy was his son. “I bought him a Samsung phone for his birthday. But that’s just the start of it. Next they want an Internet connection. At the moment they all go to the library after school, where they can log on to the Wifi. But my son has to catch the bus straight home after school.”

I thought of how we had passed through Taumarunui on the way up. It had been after-school time, and when we stopped for a piss I had heard one kid yelling to another on the footbridge over the rail tracks Skibidi Toilet, and I had thought how strange a world it is now— the Internet is a tide that washes indiscriminately over all, over enormous cities and small towns alike, homogenising and diluting. The freezing toilet seat, the sanitiser I unwisely rubbed on my hands, the floral stench of which haunted me all the way to Auckland.

We passed a lumpy hillside where the grass had been marked in round brown patches, regularly spaced, like a patterned cloth thrown over a body. He spoke suddenly— so loud I startled— and said that they poison the grass with weedkiller preparatory to planting pines. “They don’t care about anything.”

I rubbed my fingers together in the air to signify money. “Yes. Exactly. They only care about money.”

We passed a sign: Taumarunui, 70-something km. I said to Kev, “That’s most of an hour away, right?”

That was far, further than I’d thought. But we were embarked on it now. I could feel the weight of weirdness of a stranger, a breathing body, a foreign ecosystem, in the small space of the car, usually so enclosed and personal; and I thought about all the times I’ve been that stranger, all the long journeys I’ve made in strangers’ vehicles.

My first boyfriend taught me to hitch. We went around East Cape. That was a difficult hitch, because most people are only going to the next small town. It was high Midsummer, half-wild horses wandering. As we stood on the roadside between lifts he taught me to juggle.5 He taught me that you have to look interesting, smile, and make eye contact with oncoming drivers;6 and once you’re in the car, it’s your job to entertain them— don’t just sit there silently. This was difficult for me, as I was young and sullen. Hitching, then, was an early apprenticeship in charm.

“Taumarunui.” said the hitchhiker in scornful tones. “It says on the Main Trunk Line on their signs, as if they’re proud of being a railway town. But the passenger train doesn’t even stop there any more. They have old rolling stock rotting away in the yard.”

I remembered this from the way up. I could see the dead trains in my mind, hollowed-out shells, graffiti-skinned, lichenous. “Kev likes trains.” I said, pointing at Kev. Him.

“Sorry?”

“TRAINS— WE LIKE TRAINS.”

I told him that we’d been on a train. “A steam train… STEAM.”

He said that there was a bridge up ahead that a track had crossed in olden days, a line that once went up to a mine. The bridge was gone, but I saw the abutments loom like small cliffs and fall away; then, in the rear view mirror, the boxy wagons lined up on the track. I saw no reason to doubt his local history.

The road was twisty like an eel, the green hills high and studded with boulders. There were sheep, tiny lambs in woolly bell-bottoms. A herd of caramel-coloured Jerseys (“Cream cows,” I said to Kev), and another type of cow I liked, white with fine black splattered spots as if sprayed with ink by thumb-flicking a toothbrush— but Kev said they weren’t a particular breed, just a sport of mongrel cow emergent from rolling the genetic dice. A village of beehives. A small river in a deep cut, which must be the Whanganui in its infancy.7 Wild goats browsing fearlessly by the roadside. “Goaties!” said Kev, who used to keep a herd of goats. There was a particular type of goat I kept seeing, black, blue-eyed (which made them look humanoid), and horned; even the tiny kids had horns.

Kev wanted to drive, I think because of the hazardous feeling of me turning round to shout rather than watching the road. I pulled over into a small gravel dip. “Changing of the guard?” said the hitchhiker.

Now I could turn to talk to him without the danger of swerving off the road. How old was our house? he wanted to know. I said that mine was from the thirties, maybe? Kev’s was from the twenties. Sorry? I turned my head, made the word with my mouth. TWENTIES. Sorry? Now that I could see his face I saw that he had missed a small patch shaving, on his upper lip, in the divot below his nose— the philtrum. His hat and coat were weather-beaten and his shirt somewhat dirty; but his eyes were shrewd. He said that his house was built in the late 1800s, and that we should come in and see it.

What did I do for a job? I mimed typing. “You’re a typist?”

“Writer.” I said. “WRITER. …WRITER.”

“Do you write fiction? Novels?”

“No, non-fiction. NON-FICTION.”

“What do you write about?”

What I do could not be explained in a single word, not even my subject matter. I said that I write about a lot of different things. He couldn’t hear me. Trains, for instance. TRAINS. TRAINS. He was astonished. “You write about trains? Well, nobody’s going to buy a book about trains. Now sex on trains, that would sell.”

The greatest song ever written about hitchhiking, by the way, is White Valiant by The Mutton Birds. The first time I heard it, my hair stood on end: the references in it— the Valley, the quarry— made it specific to my place. It was as if the driver was speaking directly to me.

How could it be so threatening, the layering of mundane conversation? Then the twist, from horror to swelling glory: Remember it’s a white Valiant.

The hitchhiker commented again on the bumpiness of the ride. I thought that it was more the road’s fault than the car’s, and besides, beggars can’t be choosers— but I said nothing. “My car is a Volvo,” said he. “But it’s been off the road.”

“What’s wrong with it?” I said.

“Eh? What make is it? It’s a …”

“No— what’s WRONG with it.”

He paused and thought for a minute. “I … I can’t remember. It’s been off the road for … Oh, three years or so. So it must have something wrong with it.”

“It’s about nine miles to Taumarunui.” he said. “And about four miles to my house. You’ll come in and see my house— you’ll like it, if you like old houses— and have a cup of tea.”

“See that white driveway up ahead? Not that road— the one after— the white one, by the sign— slow down. Here! Drive right up to the house.”

Kev said to me, “Look— it’s the camellias. Remember? You commented on them on the drive up.”

The road was lined with big old camellia trees, relic of some farmer’s obsession, maybe. Camellias, that rot and fall as soon as they bloom.

There was the tall open-fronted garage, with the Volvo in it, cobwebbed, and another vehicle, both up on blocks. There was a pile of logs on the lawn that the hitchhiker said he could make short work of, if he had a chainsaw. The farmhouse: there was his porch and his front door and his kitchen, a large high-ceilinged room, a kitchen table. I pulled out a heavy chair. Cold it was in there, so close to the mountain. There was an old-fashioned cast-iron coal range, though, of good make, and I remarked on it. “Look, Kev. It has glass doors.”

Kev said he knew those ones— they were pricy. The hitchhiker said that the firebox was a bit small, but when it got cranking, the whole stove glowed. It made water hot— not much, but some— and you could cook on it.

“You’ll have a meat pie?” said the hitchhiker. He was getting them out of his fridge, which I saw was well-stocked. No, thank you, but no, we said. He was put out that we refused his pies. What was he going to do with them, then? He couldn’t eat them. A ham sandwich? I could make it, he told me. The boxed frills of pink meat. No, thank you, really, we had eaten a few towns back. Which town? Pirongia, said Kev. PIRONGIA. PI-RONG-I-A. The hitchhiker couldn’t understand, which I thought strange, as the town wasn’t too far away.

“Have a look around,” he said. “Look at the house.”

I wandered into the adjoining living room. A child’s drawings on the table in coloured ballpoint. A war scene— planes, bombs, the usual; a grinning bearded face, with pointy ears and too many teeth; and the boy’s name— Lloyd, the block Ls coloured in with patterns. I flipped a few pages, feeling like I was violating a stranger’s privacy, but there was little else.

On the walls were framed reproductions. “Vermeer.” I said to Kev. “Vermeer corner over here. And… Renoir. All the rest are Renoirs.”

Vermeer and Renoir: a strange combination. The purity of the Vermeers, their bare rooms, their watery Dutch light going more subtle with fading, and the blowsy soft Summertime Renoirs, with their coins of sun and their jolly sparkling maidens.

The kettle had boiled. Was rooibos OK? I was relieved at that, as I’d expected gumboot, and I didn’t relish the prospect of trying to explain it being too late for caffeine. “You’ll pour it. Cups are there,” he said to me. It didn’t strike me as sexist, necessarily— not the make a sandwich type of misogyny, I mean— he had put the cups out, and the teabags into them, but his hands were shaky. The kitchen chairs were substantial, foursquare, solid turned wood with knobs on. How strange the turns of fate that lead into a stranger’s house; every house you pass on a journey across country is a house just like this one, that is, a box containing the meaningful lives of strangers. The vertigo of that idea. How would it be, I always wondered, to live in one of those tiny towns you pass through, blink and gone?

It was good, actually, the hot cup of tea, the mug warming my cold hands. He had the hotplate off the stove, and was poking kindling into the hole. He went outside, and came back with a container of something that he sloshed into the top, then a bit more, then he opened the front door of the firebox and threw some in there, too.

“Do you think this will light?” he asked us slyly.

Kev: “I reckon it will.”

Kev, to me, when the hitchhiker was outside putting the canister away: “What was that?”

Me: “Diesel.”

Kev: “Could you smell it?”

Me: “It was written on the container.”

Kev: “It couldn’t be petrol. Or— BOOM.”

He was back now, to continue his stove-lighting performance. He lit a gas element with a long barbecue lighter, then ripped a page out of a raggedy-spined exercise book, twisting it into a loose torch to carry the flame the few feet from blue gas-ring to firebox. Lucifer. He dropped the paper into the fuel-soaked wood. There was black soot on his hands as he sat down to drink his tea, and as Kev asked him where he was born. “Where do you think I’m from?”

Kev said he thought he was from the North of England. “You think I have a Northern accent? Well… I went to school in Lancashire.” I thought of Hughes again, and of Terry’s song: In went the lads, and they began to cheer, for tattooed on her skin was all the towns of Lancashire.

He told us that he had been born in North Wales. He said that in Wales— where he still owns a house— you can tell if someone is Welsh by whether they can say the name of their town. Me: “What’s the name of your town?”

Him: “Llangollen. Some English people say Langolen.”8

Me: “Difficult!”

Him: “No, not really.”

I guess in the context of Welsh towns, there are gnarlier ones.9 But I meant the double-L sound, a hard one for non-Cymraeg-speakers. His son’s name, with the double-L; my Mum’s family name, with the same double-L. I said that I had been learning a bit of Welsh. He was baffled. “Why would you do that? Hardly anyone speaks it, even in Wales.”

Alla i ddim siarad Cymraeg. Ydych chi'n siarad Saesneg? Oes rhywun yma sy'n siarad Saesneg?10

Me: “Songs, you know. SONGS. We’re singers— we sing folk songs— FOLK SONGS. FOLK? FOLK … MUSIC. WE— we SING.” I was trying to do my mime for singing, hand opening palm-up in front of the mouth. He couldn’t understand. Like— what would you do that for?

“Do you have any children?” he asked us. I shook my head no. But pointing to Kev—“HE has one. ONE.”

The hitchhiker was taken aback. “One? That’s not very many.”

He said this as if disappointed in our lack of natural fecundity. “How many do you have?” I asked him, expecting maybe a dozen.

“Oh, I have two older ones. Then the little one.” He named where the older two lived, places in New Zealand.

Today in the street I saw a stranger I’d previously written about, and told them I had written about them. It’s not the first time that’s happened. (The first time it was the guy on the train in this piece, the second time it was the guy on the train in this piece.) New Zealand is so small that I have to assume that anyone I write about will, at some point, read what I’ve written. Telling tales is a kind of betrayal. As Richard Flanagan says, That’s life.

He was telling us about Zimbabwe now, where he lived later. “Were you a farmer?” I asked.

No, he said. He was a civil engineer. He built many dams. He still owned a house in Zimbabwe. His son had gone to school there, and it was a better education there, stricter. Beatings, of course, but that’s what people there want: they want their children to learn. When his son came back here, he had to go up a grade, as he was academically ahead of everyone else. He would prefer his son to go to school in Africa, where he would receive a proper education.

I had read about Zimbabwe recently, in a Paul Theroux essay. (Theroux takes a terrifying ride with a bitter ex-farmer. The book is Figures in a Landscape: I’d found it in a little free library.)

My other Zimbabwean association was the poster of the Bhundu Boys on Brian’s wall, for a long-ago gig at the Lemon Tree, Brian’s Aberdeen local. I had spent many hours staring at the incomprehensibly dark photo on the poster, trying to make it out. I knew of the Bhundu Boys that some of them had died of AIDS, because I had an ex-boyfriend who was obsessed with Zimbabwean guitar music as the epitome of musical greatness.11

The hitchhiker said how after Mugabe came to power, everything was fine for a while, then the soldiers began to demand their pay for putting him there. There had been a bank account, with millions set aside for the purpose of paying the soldiers, but when they looked, it was empty: it had all been spent. So then they thought they would pay the soldiers in land instead of money. Any poor land they gave to the soldiers, but any good land Mugabe gave to his cronies and his children.

Anyway, said the hitchhiker, he himself had never had any trouble in Zimbabwe, they were good people there.

(Later, what Kev remembered was the hitchhiker telling us about civil engineering and dams, and that he had said how in England people ran farms sensibly by bringing in contractors— hire someone to plough, hire a combine harvester, hire this, hire that— but in Zimbabwe the farmers kept their little villages of farmworkers, as if they were old time lairds. Engineering and farming: Kev’s purview.)

The clock on the wall was wrong. Stopped, maybe. I could feel Kev was impatient to go, but I hadn’t finished my tea. I indicated with my hand where I was down to, on the cup side. I was curious to see the boy, but I saw now that we would miss him: we were just too early for school to be over yet. Just under ten years ago this man had impregnated someone. And now there was no sign of her. It was just him and the child, washed up here. As we stood to leave Kev asked him his name. “Charles.”

“Kevin.” said Kev. “KEVIN. KEV-IN.”

An Irish name, said Charles. (Saint Kevin, according to Blindboy, had blackbirds build a nest in his hand, and held his hand in the air until the baby blackbirds hatched and fledged.)

…And Rosie. “Margaret.” said Charles. “Kevin, and Margaret.”

This was funny, because Evie had been telling us the other night at dinner how she thought Margaret was the most horrible name in the world, and I had been telling her that Princess Margaret was a glamorous bad-arse who basically just stole whatever took her fancy from people’s houses.12

He turned to me. “Rosie.” I said. “ROSIE.”

“But you just said your name was Margaret!”

We went out onto the porch and I mentioned that the boy would be home from school soon. THE BOY. The little one, the child. As we approached the car, he told me I had a beautiful smile, and my back went up, the smile froze on my face, suddenly unfree— how dare you, I thought, I did you a favour!— but I just said “Thanks.” He was a person from the past, a man of old, and there was no reasoning. He was what he was. It was not possible for him to know me.

As we drove away I said to Kev that being so deaf, one would think of getting hearing aids. But he had acted as if he wasn’t deaf; as if the fault was ours, somehow. The way every idea had to be boiled down to a single word or a hand-sign to be conveyed— it was like speaking another language one didn’t really speak.13 And the broken-down old car— but he wasn’t poor, with houses in three countries. Maybe he wasn’t allowed to drive, I said. Maybe he had Parkinsons, or something: the slight shakes. “There was an empty wine bottle on the table,” said Kev.

On Kev’s phone was the cover of the Bellamy album, where I’d paused it.

It was as if I’d summoned him by Kipling incantations: the old Africa hand, washed up here at the edge of Empire. Sex, short skirt, smile. I would never have gone to his house by myself.

A few nights later we were telling Brian about the hitchhiker. Kev said that if he passed that way again, he would definitely knock on Charles’s door for a cup of tea. (That surprised me, because I had done most of the talking, and Kev had seemed keen to wrap things up.) We kept talking it over, trying to get at what was so strange about him. He was deeply eccentric, but it was more than that. He was like a time traveller, a person from 40 or 50 years ago. Kev said how for instance, Brian was bald, therefore he kept his hair cropped; and he himself was grey, but you know, whatever— but Charles dyed his hair. “Do you remember,” said Kev, “How every second ad on the telly used to be for Grecian 2000?”

There was also the uncanniness of us having noticed and commented on his house on the way up, and then finding ourselves inside it on the way down. There was the way that his deafness meant he could speak to us but we couldn’t speak to him, or only in the simplest of terms. I said that I thought the strange thing was his complete lack of self-consciousness or shame. Kev mentioned the way he had complained about the bumpiness of the ride (rude, LOL!), and: “We did him a pretty big favour, but he didn’t say thanks!”

To me, though, there’s something admirable in that— stubborn pride, or at least acceptance of is-ness, without the compulsion to explain or apologise. Manners are often unnecessary. Someone asks for help, someone else helps, some days you are the asker, some days you are the giver. No big deal, that’s just the way it is. Where I grew up people went round to other people’s houses without phoning first. Kev’s final assessment: “North Wales. Zimbabwe. Taumarunui. He was from the country, not the city.”

The word I originally used to describe Taumarunui, then deleted for its city-snob vibe, was backwater. But as I made my coffee just now— I think it was when the snowmelt-feeling tap water hit my hands— I thought, Well, rub away the colonialism and it is a true descriptor. It depends on where you are looking from, how you are looking. Back when the river was the road, Taumarunui was a place of major importance; its backwaterness was the very heart of its power. Please forgive my ignorance: it’s not my place. I mean that literally— it’s not a place I know. A cursory search reveals that Taumarunui is where the Ongarue and the Whanganui conflow— the confluence of two major routes to the interior. Olden day people were not lazy like us moderns, drifting down the current for fun like a kid on an inner tube: they paddled upriver, and portaged their waka from one water to another. Even in modern times the Whanganui river remained the main way up to Taumarunui, because it was easier to navigate than roads. (That was / is true for many towns on the river.) The road’s way and the rail’s way search for the easiest course; but they only imitate water’s Dao.14

A memory of journeying by the river way. We were a kayak flotilla. The banks were high hills of dense forest, green gorges strung with tūī calls such as I’d never heard before. Osha and I shared a boat and sang as we paddled. I accidentally dropped my harmonica into the bilge water. Many days into the journey, when the river was growing broad and calm, we came ashore one evening at a place that had a marae on one side of the river and a pub on the other. Civilisation! Humankind! We walked up to the pub, which I don’t remember— were we the only ones there, was there a pool table? I do remember the walk down afterwards, the galaxies of pale blue glow-worms patterning the wet black banks as we rolled down towards our tents. Suddenly the church bells rang out from across the river, rolling over the muscled water-being’s back— it was midnight— it was New Year’s Day.

I wrote about the straight line thing here: “it was a constitutional. But in recalling the walk now, I see that remembering along a narrow path is easy. It’s a single narrative thread: you just re-walk the path in your mind and what happened arises in sequence. (What happened this time, and also what happened other times.)”

I was researching Ford o' Kabul River:

This was the version I'd heard, but I wanted to hear it straight from the horse's mouth. You can always pick out Bellamy from a mass of harmonies, to discern a clear tune: he’d a voice like a knife— maybe a kris, a river-shaped knife.

Kabul town's by Kabul river -

Blow the trumpet, draw the sword -

There I lef' my mate for ever,

Wet an' drippin' by the ford.

Ford, ford, ford o' Kabul river,

Ford o' Kabul river in the dark !

There's the river up and brimmin',

An' there's 'arf a squadron swimmin'

'Cross the ford o' Kabul river in the dark. Kev: “He looked like a gentleman.”

What I got for my birthday, plus other random gifts from my birthday week in Auckland:

Seasonal yearly wall planner (starts in Spring) made by my friend Lily, paid for by my Mum; Aberlour 12 year from my Dad; plum jam made by my brother-out-law Dustin, swapped for my blackberry jam; a white egg from one of my Mum’s chickens; scones baked by Janie (inside the brown wax paper package); tiny Hoya serpens cuttings from my sister; shirt from James; two kinds of Scindapsis pictus cuttings from a random plant-Wizard I met at a café; two-CD Handel’s Messiah by The Academy of Ancient Music, also from my Dad, featuring the wonderful tenor Paul Elliot, whose voice is like a statue of Apollo carved from butter:

First step: practise lobbing the ball from hand to hand without looking at your hands. When you’ve mastered that, use two balls to practise the swap, both left and right-handed. The trick is, the juggling balls have to pass under each other at the changeover, not in front of each other: imagine them as passing side to side between two panes of glass set a ball-width apart. Just one arrow in my quiver of entertaining-but-useless party tricks.

It’s important to keep a good state of mind, or people won’t pick you up. They can feel if you’re angry or impatient. It’s also important that your face be visible. Hats, glasses, hoods, umbrellas, will all diminish your chances.

When you kayak the Whanganui— which I’ve done twice, in my youth— you get in at Taumarunui.

Kev says he told us he was born in Wrexham, near Llangollen and very near the border, and that his Grandmother sent him to school in England because she didn’t want him to grow up ‘too Welsh’.

For instance:

Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch is the second-longest town name in the world; the longest name— as jem547 points out in the comments— is here.

“Here in New Zealand we have a place in the North Island called “Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronukupokaiwhenuakitanatahu’, which translates from Māori to: ‘The summit where Tamatea, the man with the big knees, the slider, climber of mountains, the land-swallower who travelled about, played his kōauau (flute) to his loved one.”

(Pronunciation: POV: Gen Z Māori baby names be like...)

Other Aotearoa v. Cymru feuds— aside from the rugby— include who has the steepest street (again, it’s us, sorry): Welsh street loses world's steepest title after New Zealand rival's appeal

‘I don’t speak Welsh. Do you speak English? Is there anyone here who speaks English?’

It could be worse. See also: reggae; flamenco.

The Bhundu Boys famously made John Peel cry with joy the first time he saw them live.

More about the Bhundu Boys here: Jinxed: the curse of the Bhundu boys.

“They had learnt their trade in the less than salubrious nightspots of Harare, playing from 7pm until 4am without a break and often without acknowledgement or recognition. 'In Zimbabwe, if you play for only one-and-a-half hours, people will stone you to death,' says [Rise] Kagona, matter-of-factly. Glasgow must have felt a little like home.”

More mind-boggling Margaretalia here: Always the Same Dream - Ferdinand Mount

“Richard Eyre said that ‘if it weren’t for the sharp English upper-class voice, you’d say she looks like a Maltese landlady.’ Cecil Beaton described her as vulgar and later as ‘a poor midgety brute’ who had ‘gone to pot ... her complexion now a dirty negligee pink satin’. Only matched by Alan Clark’s diary entry: ‘fat, ugly, dwarflike, lecherous and revoltingly tastelessly behaved.”

I remembered the time my fountain pen was running out of ink, and I knew it only had a few words left in it. That got me thinking about how small it was possible for a poem to be. Could one word be a poem?

Snow

Or was it necessary for a poem to have two words, for there to be a narrative / tension?

Mountain

Cloud

Famously, in 2017 Whanganui awa became the first river in the world to be granted legal personhood.

After I published this, I went down to Brian's. Kelly came in holding a pitchfork (American Gothic). Then I went to the beach, where there were severed camellia branches twined in the seaweed.

"a line that once went up to a mine" There were mines and sawmills along the route, but actually the line to Stratford, Taranaki via Whangamomona. This now hosts the tourist attraction 'Forgotten World Adventures' where you can travel the entire line in a self-drive buggy-on-rails type vehicle.

Kiwirail has said that the re-opening of this line to traffic is a priority- since it creates an alternative route to the difficult 'Main Trunk Line' section from Marton to Taumaranui via the Volcanic Plateau*. Fat chance of that happening under this government.

*Following the 1953 Tangiwai disaster, this was a lifeline to the NIMTL.